Green Light: How a Jellyfish Protein Illuminated the Inner Workings of Life

The story of Martin Chalfie's Nobel Prize-winning work with Green Fluorescent Protein

The Spark of Discovery: From Jellyfish to Nobel Prize

Imagine trying to understand the intricate workings of a watch by only observing its exterior—you might hear ticking but could never see the delicate gears and springs moving in synchrony. For centuries, this was the challenge facing biologists trying to understand living cells.

That all changed with one of the most transformative tools in modern biology: the Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP), which functions like a molecular flashlight that can illuminate specific structures and processes within living cells 1 .

The 2009 Lindau Nobel Laureate Meeting featured one of the key architects of this revolution: Martin Chalfie, who just one year earlier had shared the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his groundbreaking work with GFP 1 2 .

His presentation wasn't just a story of a brilliant discovery; it was a testament to the power of curiosity-driven basic research and the unexpected paths that often lead to scientific breakthroughs. Chalfie's journey—from a temporary high school teacher to Nobel Laureate—demonstrates how fascination with seemingly obscure natural phenomena (like why a jellyfish glows) can transform entire fields of science 1 8 .

The Glowing Protein That Changed Biology

What is GFP and Why Does It Matter?

Green Fluorescent Protein is a naturally occurring protein found in the crystal jellyfish (Aequorea victoria) that emits a characteristic green glow without needing any additional components or substrates—just exposure to blue or ultraviolet light 1 .

What makes GFP truly revolutionary is its versatility as a biological marker. Scientists can genetically engineer cells to produce GFP attached to other proteins of interest, effectively tagging them with a fluorescent beacon 1 2 .

Key Properties of GFP

- Self-sufficient fluorescence

- No toxic substrates required

- Works in living cells and organisms

- Can be fused to other proteins

- Stable across wide pH range

The Key Experiment: Lighting Up Life

1989: The Spark of Inspiration

When Martin Chalfie first heard about GFP during a seminar, he immediately recognized its potential for his work on the nervous system of the transparent roundworm C. elegans 1 .

1992: The Breakthrough Experiment

Chalfie, his rotation student Ghia Euskirchen, and technician Yuan Tu successfully demonstrated that GFP could function as a universal genetic tag 1 .

Step 1: Isolating the GFP Gene

They obtained GFP DNA from Douglas Prasher and used PCR to amplify only the coding sequence, avoiding extra sequences that had prevented successful expression in other labs 1 .

Step 2: Initial Expression in Bacteria

Euskirchen expressed GFP in E. coli bacteria and captured images of glowing green bacteria—conclusive proof that GFP could fluoresce on its own without any jellyfish-specific components 1 .

Step 3: Expression in Living Organisms

Yuan Tu then expressed GFP in C. elegans, specifically in the touch receptor neurons. This successfully created transparent worms with six specific neurons glowing green 1 .

1994: Landmark Publication

Their findings, published in the landmark Science paper "Green Fluorescent Protein as a Marker for Gene Expression," opened the door for countless researchers to adapt GFP for their own studies 1 .

Key Research Reagents Used in the GFP Breakthrough Experiment

| Reagent/Resource | Function in the Experiment | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| GFP DNA from jellyfish | Source of the fluorescent protein | Provided the fundamental material for genetic engineering |

| PCR amplification | Isolated the coding sequence | Avoided problematic extra sequences that prevented fluorescence |

| E. coli bacteria | Initial test organism for GFP expression | Proved GFP could fluoresce independently in other species |

| C. elegans roundworms | Primary model organism for neuronal expression | Demonstrated GFP worked in complex, multicellular organisms |

| Specialized microscope | Visualized weak fluorescence | Essential for detecting and documenting the initial results |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials for Biological Imaging

The GFP revolution required more than just the glowing protein itself—it depended on a suite of scientific tools and reagents that enabled researchers to harness its power.

Genetic Materials

Engineered DNA constructs and expression vectors that carry GFP genes into target cells and organisms.

Molecular Biology Tools

PCR reagents and techniques to amplify and modify GFP genetic sequences for expression.

Imaging Equipment

Fluorescence microscopes to visualize and document GFP fluorescence in living samples.

Model Organisms

Living systems like C. elegans and E. coli as test subjects for developing and applying GFP technology.

Essential Research Reagents in GFP-based Biology

| Tool/Reagent | Category | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| GFP DNA constructs | Genetic material | Engineered to fuse with genes of interest to tag proteins |

| Model organisms (C. elegans, E. coli) | Living systems | Test subjects for developing and applying GFP technology |

| PCR reagents | Molecular biology tool | Amplify and modify GFP genetic sequences for expression |

| Expression vectors | Delivery system | Carry GFP genes into target cells and organisms |

| Fluorescence microscopes | Imaging equipment | Visualize and document GFP fluorescence in living samples |

A Brighter Future: The Lasting Impact of GFP

Revolutionizing Cellular Imaging

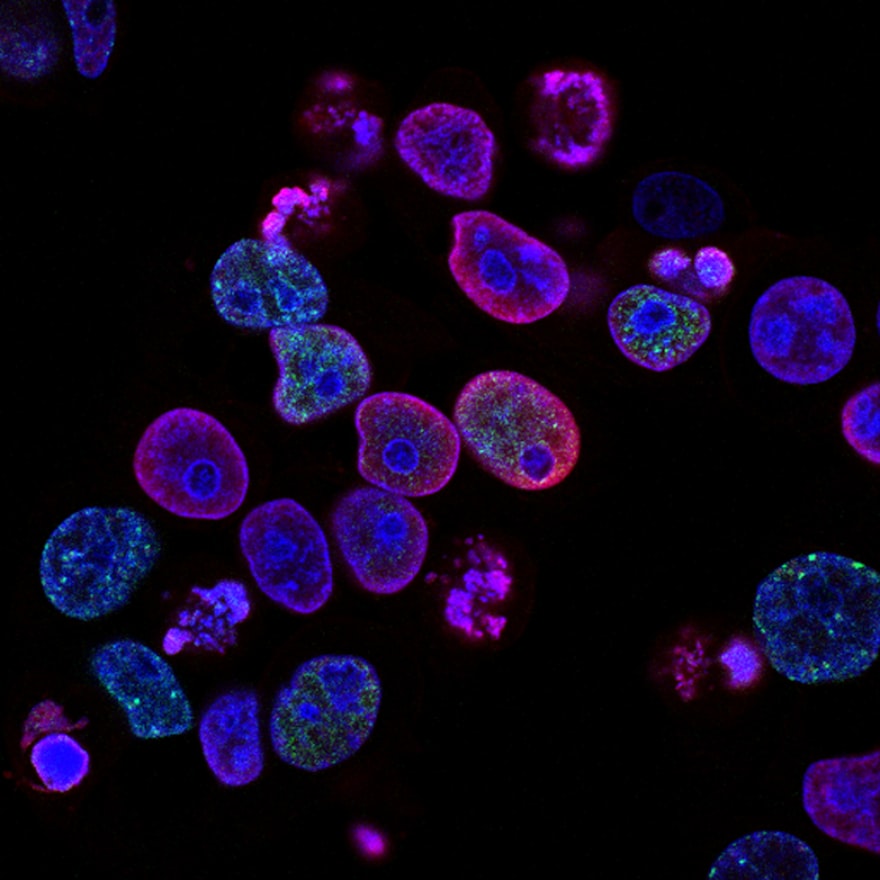

Since Chalfie's initial breakthrough, GFP and similar fluorescent proteins have become indispensable tools across biological research. Their applications extend far beyond basic cell biology to medicine, drug development, and biomedical engineering. Scientists have engineered GFP into various colors, creating a "palette of fluorescent proteins" that can track multiple cellular processes simultaneously 1 .

This technology has enabled unprecedented views of previously invisible processes: watching cancer cells migrate through living tissue, observing the development of neurons in the brain, tracking the spread of viruses through cells, and monitoring the effectiveness of experimental drugs in real-time.

Neuroscience

Application: Tagging specific neuron types

Key Insight: Visualized brain circuitry and neural development

Cancer Biology

Application: Tracking metastatic cells

Key Insight: Observed how cancer spreads through the body

Developmental Biology

Application: Marking specific cell lineages

Key Insight: Watched how specialized tissues form from stem cells

Microbiology

Application: Tagging pathogens inside host cells

Key Insight: Understood how diseases establish infections

Drug Discovery

Application: Reporting cellular responses to compounds

Key Insight: Accelerated screening of potential therapeutics

Diverse Applications of GFP Technology in Research

| Field of Study | Application of GFP | Key Insight Gained |

|---|---|---|

| Neuroscience | Tagging specific neuron types | Visualized brain circuitry and neural development |

| Cancer biology | Tracking metastatic cells | Observed how cancer spreads through the body |

| Developmental biology | Marking specific cell lineages | Watched how specialized tissues form from stem cells |

| Microbiology | Tagging pathogens inside host cells | Understood how diseases establish infections |

| Drug discovery | Reporting cellular responses to compounds | Accelerated screening of potential therapeutics |

Championing Basic Research and Future Scientists

At the 2009 Lindau Meeting, Chalfie didn't just present his scientific work—he emphasized a crucial philosophy about scientific progress. He argued passionately for the importance of basic, curiosity-driven research and warned against focusing exclusively on immediate practical applications 1 .

The GFP story itself stands as a powerful example: the initial discovery came from studying bioluminescence in jellyfish, a topic with no obvious practical application that ultimately revolutionized biological imaging.

Chalfie also used his platform to encourage the next generation of scientists, reflecting the core mission of the Lindau Meetings to foster dialogue between established researchers and young scientists 9 . His own career path—with its twists, turns, and initial setbacks—serves as an inspiring example for early-career researchers facing their own challenges 1 .

Curiosity-Driven Research

The importance of exploring fundamental questions without immediate practical applications.

Martin Chalfie's Honors and Recognition

Nobel Prize in Chemistry

Year: 2008

Organization: Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

E. B. Wilson Medal

Year: 2008

Organization: American Society for Cell Biology

Golden Goose Award

Year: 2012

Organization: United States Congress

Foreign Member of the Royal Society

Year: 2018

Organization: Royal Society of London

Awards and Honors

| Award | Year | Recognizing Organization |

|---|---|---|

| Nobel Prize in Chemistry | 2008 | Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences |

| E. B. Wilson Medal | 2008 | American Society for Cell Biology |

| Golden Goose Award | 2012 | United States Congress |

| Foreign Member of the Royal Society | 2018 | Royal Society of London |

| Lomonosov Gold Medal | 2018 | Russian Academy of Sciences |

The Enduring Glow of Scientific Curiosity

The story of GFP, as presented by Martin Chalfie at the 2009 Lindau Nobel Laureate Meeting, represents far more than a technical achievement in laboratory methods. It stands as a powerful testament to the unpredictable nature of scientific discovery and the profound impact that can emerge from studying seemingly obscure natural phenomena.

The green glow that evolved in jellyfish to startle predators or attract prey has become one of the most important tools ever developed for understanding life at the cellular level.

More than a decade after Chalfie's Lindau presentation, GFP continues to enable new discoveries and has spawned an entire family of fluorescent proteins that light up cells in all colors of the rainbow. This legacy continues to grow as each new generation of scientists finds innovative ways to use these molecular flashlights to explore the remaining mysteries of life.

"We should be a little freer and investigate things in different directions, and be a little bit awed by what we're going to find" — Martin Chalfie 1