Modeling Neurodevelopmental Disorders with Human iPSCs: From Foundational Mechanisms to Translational Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of how human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) are revolutionizing the study of neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs).

Modeling Neurodevelopmental Disorders with Human iPSCs: From Foundational Mechanisms to Translational Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of how human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) are revolutionizing the study of neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs). Covering foundational principles to cutting-edge applications, we explore the transition from traditional 2D models to complex 3D organoid and assembloid systems that better recapitulate human brain development and disease phenotypes. The content details advanced methodological approaches, including CRISPR genome editing, functional neuronal assays, and machine learning integration, while addressing key challenges in standardization, scalability, and clinical translation. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes how iPSC-based models are accelerating disease mechanism discovery and creating new pathways for therapeutic development in conditions affecting the developing human nervous system.

The iPSC Revolution: Establishing Human-Centric Models for Neurodevelopmental Disorders

The study of neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders has long relied on animal models. While these models have provided foundational knowledge, they fundamentally lack human-specific biological context, often leading to findings that fail to translate to human patients. Animal models face significant challenges in recapitulating human brain complexity due to evolutionary divergence in brain structure, function, and genetics [1]. For instance, key parameters such as heart rates differ dramatically between species (zebrafish: 120-180 bpm; mice: 300-600 bpm; humans: 60-100 bpm), reflecting profound underlying physiological differences that complicate direct translation of neurological findings [1]. Furthermore, species-specific disease mechanisms often mean that pathologies observed in animals do not fully mirror human disease states, particularly for complex neurodevelopmental disorders like schizophrenia or autism spectrum disorders [2].

The emergence of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology has revolutionized neurological disease modeling by providing access to functional human neural cells and systems. iPSCs are particularly valuable for neural research because they can be derived from patients with known symptom histories, genetics, and drug-response profiles, capturing the full genetic complexity of polygenic brain disorders in a human-relevant system [2]. This approach enables researchers to move beyond the limitations of animal models to create human neural systems that authentically replicate disease mechanisms and developmental processes.

The iPSC Revolution in Neural System Modeling

Fundamental Principles and Advantages

The development of iPSC technology by Takahashi and Yamanaka in 2006-2007 represented a paradigm shift in disease modeling [3]. By reprogramming somatic cells to a pluripotent state using defined factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, MYC), researchers gained the ability to generate patient-specific neural cells that retain the complete genetic background of the donor [3]. This technology provides three critical advantages for neural research: (1) the capacity for unlimited expansion of patient-specific neural progenitors, (2) amenability to genetic engineering using CRISPR/Cas9 to create isogenic controls, and (3) the ability to differentiate into diverse neural and glial subtypes relevant to specific disorders [2] [3].

iPSC-derived neural models effectively capture human-specific aspects of brain development that cannot be studied in animal models. Notably, human brain development features a protracted period of neurogenesis and interneuron migration that extends into the postnatal period—a uniquely human characteristic with profound implications for neurodevelopmental disorders [4]. Recent findings in postmortem tissue have revealed that cortical interneuron migration continues after birth, "shed[ding] light on a prolonged stage of human brain development and a longer plasticity window for fine-tuning of the developing circuit with local inhibitory inputs" [4]. This extended developmental window also presents a wider vulnerability to insults that may lead to neurological disorders such as autism and epilepsy [4].

Technical Validation of iPSC-Derived Neural Models

Extensive validation studies have confirmed that iPSC-derived neural cells accurately model human neural development. Molecular marker analyses, morphological assessments, and functional assays demonstrate that iPSC-derived neurons exhibit characteristics of authentic human neural cells [2]. Transcriptome-wide approaches using single-cell RNA sequencing have enabled high-dimensional, unbiased validation of iPSC-derived cellular models, confirming they give rise to heterogeneous, region-specific cell types [2].

Temporal analyses consistently show that iPSC-derived neurons correspond to prenatal developmental stages, most commonly resembling the second trimester of human gestation [2]. This developmental timing makes them particularly suitable for studying neurodevelopmental disorders that originate during early brain development. While this fetal-like state presents challenges for modeling late-onset disorders, recent advances in prolonged culture systems and maturation protocols have extended the developmental timeline accessible to researchers [4].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Neural Model Systems

| Model Characteristic | Animal Models | iPSC 2D Models | iPSC 3D Organoids/Assembloids |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human genetic background | No (unless humanized) | Yes | Yes |

| Developmental stage captured | Species-specific | ~Second trimester human equivalent | Multiple developmental stages |

| Cellular diversity | Species-specific repertoire | Limited by protocol | High diversity, self-organizing |

| Circuit complexity | Intact but non-human | Limited connections | Emerging complex connectivity |

| Neuroinflammatory components | Limited human relevance | Limited | Advanced (microglia, astrocytes) |

| Throughput for screening | Low | High | Medium |

| Maturation timeline | Fixed developmental program | 30-90 days | Up to 390+ days [4] |

Advanced Human Neural System Architectures

From 2D Cultures to 3D Organoids and Assembloids

Early iPSC neural models primarily consisted of two-dimensional monocultures of specific neural subtypes. While these provided important insights into cell-autonomous disease mechanisms, the field has progressively advanced toward more complex three-dimensional systems that better replicate the cellular diversity and spatial organization of the human brain [3]. Cerebral organoids—self-organizing 3D structures that contain multiple neural cell types—represent a significant advancement, exhibiting features of regional specification and layered organization reminiscent of the developing human brain [3].

The most recent innovation involves assembloids—integrated systems combining multiple organoid types to model interactions between different brain regions. One groundbreaking study established a dorsal-ventral assembloid model that reconstitutes postnatal human interneuron migration [4]. This model, maintained for up to 390 days in culture, demonstrated that "newly born migratory interneurons arrange themselves into connected chains that are surrounded by astrocytes," replicating the architectural and migratory patterns observed in early postnatal human brains [4]. Electron microscopy analysis revealed "architecture essentially indistinguishable from what has been seen in early postnatal human brains," validating this approach for studying extended human brain development [4].

Incorporation of Neuroimmune Components

The critical role of neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative diseases has driven the development of iPSC models that incorporate diverse glial cell types. Recent advancements now enable the differentiation of iPSCs into microglia, astrocytes, and blood-brain barrier (BBB) components, which can be integrated into complex organoid systems [5]. These advancements are particularly relevant for modeling neuroinflammation in prevalent neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer's disease (AD), Parkinson's disease (PD), and multiple sclerosis (MS) [5].

The integration of neuroimmune components enables researchers to study cell-non-autonomous disease mechanisms, such as how microglial activation contributes to neuronal damage in neurodegeneration, or how astrocyte dysfunction impacts synaptic pruning in neurodevelopmental disorders. These human-specific neuroimmune interactions cannot be adequately modeled in animal systems due to significant species differences in immune function and inflammation responses [5].

Application to Neurodevelopmental Disorder Research

Modeling Genetic Complexity in Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia (SCZ) research exemplifies the power of iPSC systems to address polygenic complexity. Despite high heritability, genome-wide association studies have identified numerous risk variants with low penetrance, making it difficult to establish causal relationships [2]. iPSC models capture the complete genetic background of patients, enabling researchers to study how multiple genetic variants interact to produce disease phenotypes.

A recent innovative approach addressed this complexity through "village editing"—CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing in a cell village format [4]. Researchers generated NRXN1 knockouts in iPSC lines from 15 donors with low, neutral, or high polygenic risk scores for SCZ, achieving high editing efficiency (heterozygous: 33.1%; homozygous: 28.4%) [4]. After differentiation into cortical excitatory neurons, transcriptomic analysis revealed that "genetic background deeply influences gene expression changes in NRXN1 KO neurons" [4]. This demonstrates the critical importance of incorporating multiple genetic backgrounds when studying polygenic disorders and provides a framework for efficient development of similar tools for other complex disorders.

Elucidating Disease Mechanisms in Rare Genetic Disorders

For monogenic neurodevelopmental disorders, iPSC models enable precise dissection of disease mechanisms. In Hereditary Sensory and Autonomic Neuropathy Type IV (HSAN IV), caused by mutations in NTRK1, iPSC-derived dorsal root ganglion (DRG) organoids revealed a previously unknown disease mechanism: "DRG organoids derived from HSAN IV patients underwent a lineage switching between sensory neurons and glial cells without affecting the neural crest stem cell population" [4]. This lineage switching, characterized by reduced sensory neurons and premature gliogenesis, represents a novel pathological mechanism that could not have been identified in animal models [4].

The use of isogenic controls—patient-derived iPSCs in which the disease-causing mutation has been corrected using CRISPR—eliminates confounding genetic variability and provides definitive evidence of mutation-specific effects [4]. This approach is particularly powerful for validating potential therapeutic targets by demonstrating that phenotype rescue occurs specifically upon mutation correction.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for iPSC Neural Disease Modeling

| Research Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Example in Neurodevelopmental Research |

|---|---|---|

| Sendai virus, episomal plasmids, mRNA | Non-integrating reprogramming methods | Generating integration-free iPSCs from patient fibroblasts or blood cells [2] |

| CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing | Creating isogenic controls; introducing mutations | NRXN1 knockout in multiple genetic backgrounds [4]; correction of NTRK1 mutations [4] |

| Neural patterning molecules | Directing differentiation to specific neural fates | Generating cortical excitatory neurons, GABAergic interneurons, etc. [2] |

| OP9 stromal cells | Supporting hematopoietic differentiation | Co-culture system for iPSC differentiation [6] |

| Tandem Mass Tag (TMT) labeling | Multiplexed quantitative proteomics | Comparing proteomes of iPSC-derived cells vs. primary cells [6] |

| Single-cell RNA sequencing | High-resolution cell type characterization | Validating neuronal subtypes; identifying novel populations [2] |

Methodological Framework for iPSC Neural System Experiments

Experimental Workflow for Disease Modeling

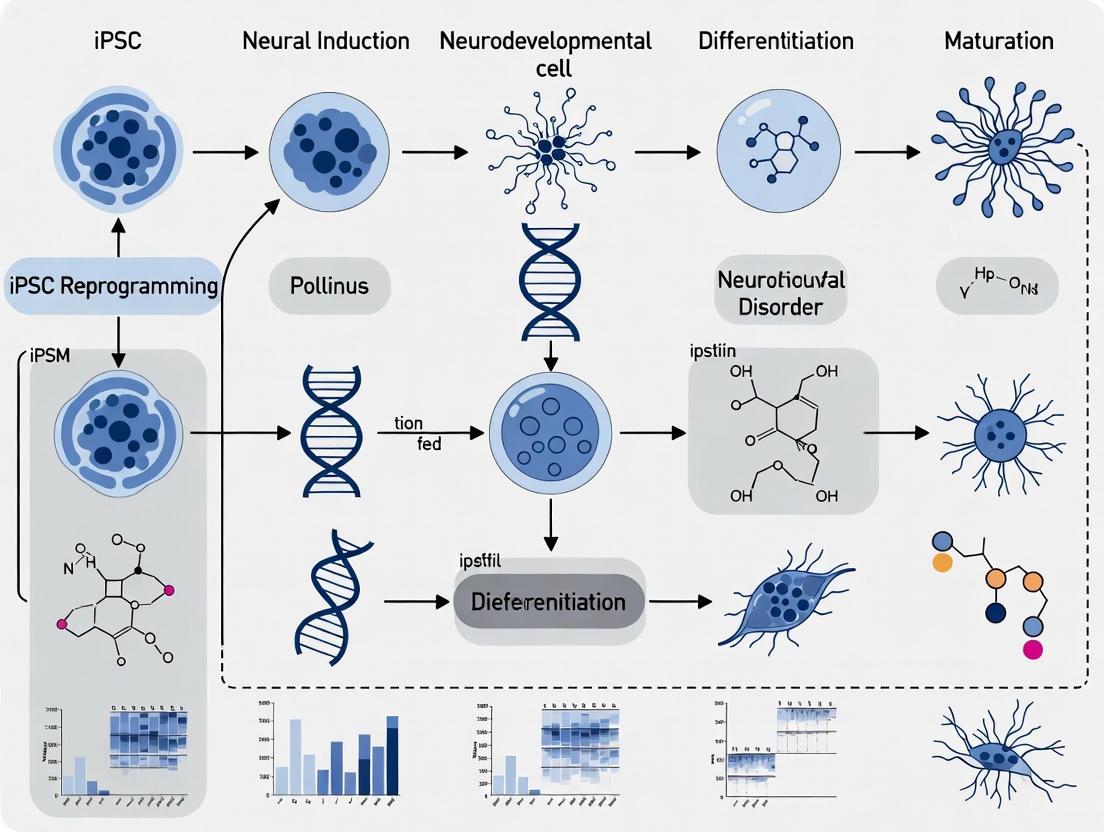

The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive workflow for iPSC-based modeling of neurodevelopmental disorders:

Protocol for Dorsal-Ventral Assembloid Generation

The assembloid model of interneuron migration represents a cutting-edge approach for studying human-specific developmental processes [4]. The detailed methodology includes:

Independent Differentiation: Dorsal (cortical) and ventral (ganglionic eminence) organoids are differentiated separately from iPSCs using established patterning protocols with appropriate morphogens.

Fusion Protocol: After 120 days of differentiation, dorsal and ventral organoids are placed in contact in low-adhesion plates to enable fusion.

Long-term Maintenance: Fused assembloids are maintained for extended periods (up to 390 days) with careful feeding schedules and periodic assessment.

Migration Analysis: Interneuron migration from ventral to dorsal compartments is assessed using time-lapse imaging, immunohistochemistry for CGE markers, and EdU birth dating to confirm late-born interneuron populations.

Validation: Electron microscopy and single-cell spatial transcriptomics validate architectural features and molecular signatures comparable to postnatal human brain tissue [4].

This protocol successfully reconstitutes "events of human brain development that occur after birth, allowing a genetic and cell biological analysis of this important phenomenon" [4].

Protocol for Village Editing Approach

The village editing approach enables efficient study of genetic variants across multiple backgrounds [4]:

iPSC Line Selection: Select iPSC lines from multiple donors (e.g., 15 donors) representing diverse polygenic risk backgrounds.

Pooled CRISPR Editing: Perform CRISPR/Cas9 editing (e.g., NRXN1 knockout) on a pooled "village" of iPSCs from multiple donors rather than editing lines individually.

Clonal Isolation and Genotyping: After editing, recover individual clones and genotype to identify untargeted controls, heterozygous (33.1%), and homozygous (28.4%) edits across different donor backgrounds.

Differentiation and Analysis: Differentiate edited iPSCs into relevant neural cells (e.g., cortical excitatory neurons) and analyze transcriptomic, synaptic, or other cellular phenotypes.

Background Effect Assessment: Use computational methods to determine how genetic background influences the phenotypic effects of the introduced mutation [4].

This method provides "a framework for rapid and efficient development of similar tools to study gene functions in complex, polygenic disorders" [4].

Quantitative Assessment of Model System Faithfulness

Rigorous comparison between iPSC-derived neural cells and their in vivo counterparts is essential for validating model systems. Multiplexed quantitative proteomics using Tandem Mass Tag (TMT) labeling has demonstrated that iPSC-derived erythroid cells share significant similarity with primary cells, with only 1.9% of proteins differing by 5-fold or more [6]. While direct proteomic comparisons for neural cells were not provided in the search results, similar validation approaches are being applied to neural lineages.

Table 3: Functional Comparison of Neural Model Capabilities

| Model Capability | Traditional Animal Models | iPSC 2D Neural Cultures | iPSC 3D Organoid/Assembloid Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Globin switching study | Limited relevance | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Enucleation analysis | Species-specific process | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Neural migration studies | Limited human relevance | Limited | High (chain migration observed) [4] |

| Lineage specification analysis | Requires transgenic models | Moderate | High (lineage switching detected) [4] |

| Cell-cell interaction mapping | Intact but non-human | Limited | High (neuron-astrocyte interactions) [4] |

| Drug screening throughput | Low | High | Medium |

| Transcriptomic profiling | Species-specific | Human-specific | Human-specific, spatially resolved |

Future Directions and Integration with Emerging Technologies

The next frontier in human neural system development involves integrating iPSC models with advanced computational approaches and additional technological innovations. Machine learning is emerging as a powerful tool for analyzing complex datasets generated from iPSC models and for predicting disease outcomes based on in vitro phenotypes [1]. As these models become more sophisticated, they will increasingly incorporate multi-omics approaches (transcriptomics, proteomics, epigenomics, metabolomics) to build comprehensive pictures of disease states.

Another promising direction is the development of humanized animal models through transplantation of human iPSC-derived neural cells or organoids into rodent brains, creating chimeric systems that combine the physiological context of animal models with human cellular components [1]. These approaches may provide important bridges for translational research while maintaining human biological relevance.

Furthermore, the combination of iPSC-derived neural models with advanced bioengineering approaches—such as microfluidic devices, bioprinting, and electrical stimulation—will enable even more precise control over the cellular microenvironment and more complex tissue architectures that better mimic the human brain [3].

Human iPSC-derived neural systems represent a transformative approach for studying neurodevelopmental disorders, offering unprecedented access to human-specific biology and disease mechanisms. By capturing the complete genetic background of patients and enabling the reconstruction of complex neural tissues in vitro, these models address critical limitations of traditional animal systems. The continued refinement of organoid and assembloid technologies, combined with advanced gene editing and multi-omics characterization, promises to accelerate our understanding of neurodevelopmental disease mechanisms and therapeutic development. As these human-relevant systems become increasingly sophisticated and accessible, they will undoubtedly play a central role in unraveling the complexities of human brain development and dysfunction.

The modeling of neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs) has been fundamentally transformed by technologies that enable the reprogramming of somatic cells into specific neural lineages [7]. For decades, neuroscience research was constrained by the limited accessibility of human neural tissue and the imperfect translatability of animal models, which fail to fully capture the intricacies of human-specific developmental processes [7]. The emergence of human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) inaugurated a new era, allowing researchers to derive patient-specific neurons, glia, and three-dimensional (3D) organoid systems that more accurately model human physiology and pathology [7]. These advances are particularly crucial for NDDs—a highly heterogeneous group of diseases impairing social, cognitive, and emotional functioning—as they provide direct experimental access to disease mechanisms within a human genetic context [7]. This technical guide outlines the core principles, methods, and applications of somatic cell reprogramming and neural specification, providing a comprehensive framework for researchers investigating NDD mechanisms.

Somatic Cell Reprogramming: Methodologies and Mechanisms

Historical Foundations and Key Discoveries

The conceptual foundation for somatic cell reprogramming was established by pioneering work demonstrating that cellular differentiation is not an irreversible process. John Gurdon's seminal somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) experiments in Xenopus laevis in 1962 first revealed that a nucleus from a terminally differentiated somatic cell contained all genetic information needed to generate an entire organism [3]. This principle of epigenetic plasticity was later harnessed by Shinya Yamanaka, who identified a combination of four transcription factors—OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and MYC (OSKM)—sufficient to reprogram mouse fibroblasts into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) in 2006 [3]. This discovery, followed by the successful generation of human iPSCs in 2007, established the core technology that enables the current modeling of human diseases, including NDDs [3].

Reprogramming Strategies and Technical Approaches

Multiple strategic pathways exist for converting somatic cells to neural lineages, each with distinct advantages for specific research applications. The table below summarizes the primary reprogramming approaches.

Table 1: Strategic Pathways for Neural Reprogramming

| Reprogramming Strategy | Key Features | Intermediate Stage | Technical Considerations | Primary Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Induced Pluripotency [8] [3] | Somatic cells are fully reprogrammed to a pluripotent state using Yamanaka factors (OSKM) or related combinations. | Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) | Lengthy process (months); potential for teratoma formation; captures complete developmental trajectory. | Disease modeling requiring full neurodevelopment; generation of diverse neural cell types; organoid formation. |

| Direct Lineage Reprogramming (Transdifferentiation) [8] [9] | Somatic cells are directly converted to neuronal cells using neural-specific transcription factors or small molecules, bypassing the pluripotent state. | None | Faster process (weeks); reduced tumorigenic risk; may result in incomplete maturation. | Rapid generation of specific neuronal subtypes; potential for in vivo therapeutic applications. |

| Induced Neural Stem Cells (iNSCs) [8] | Somatic cells are reprogrammed into multipotent neural stem cells capable of self-renewal and differentiation into multiple neural lineages. | Neural Stem Cells (NSCs) | Stable, expandable cell population; maintains lineage restriction; differentiates into neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes. | Studies requiring expandable progenitor populations; modeling early neurodevelopmental events. |

Molecular Mechanisms of Reprogramming

The reprogramming of somatic cells to iPSCs involves profound epigenetic remodeling that partially reverses the process of embryonic development [3]. This process occurs in two broad phases: an early, stochastic phase where somatic genes are silenced and early pluripotency genes are activated, and a late, more deterministic phase where late pluripotency-associated genes are activated [3]. Critical events during reprogramming include widespread changes in chromatin accessibility, DNA methylation patterns, and histone modifications [3]. When reprogramming fibroblasts, a key event is the mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET), which is crucial for establishing the pluripotent state [3]. The entire process entails a comprehensive resetting of the cellular state, affecting nearly all aspects of cell biology, including metabolism, cell signaling, and proteostasis [3].

Neural Lineage Specification: From Pluripotency to Neuronal Networks

Guided Neural Induction and Regional Patterning

The controlled differentiation of iPSCs into neural lineages requires precise manipulation of key developmental signaling pathways. Highly efficient neural induction can be achieved using small-molecule cocktails that suppress alternative differentiation paths while promoting neural specification [10]. One established protocol involves a "DAP" cocktail (typically containing Dorsomorphin, A83-01, and other factors) that inhibits SMAD signaling, leading to highly pure cultures of PAX6-/NESTIN-positive neural stem cells (NSCs) with greater than 97% efficiency [10]. These primitive NSCs can subsequently be patterned into specific neuronal subtypes through the sequential addition of regionalizing factors:

- Cortical Excitatory Neurons: Treatment with FGF2 and WNT antagonists promotes anterior forebrain identities, while timed WNT activation can drive posteriorization [10] [4].

- Interneuron Subtypes: Activation of SHH signaling ventralizes neural progenitor cells towards medial ganglionic eminence identities that generate GABAergic interneurons [4].

- Sensory Neurons: Combined BMP, WNT, and TGF-β signaling directs differentiation towards neural crest lineages that form sensory neurons, as demonstrated in dorsal root ganglion (DRG) organoid models [4].

Advanced 3D Model Systems: Organoids and Assembloids

Beyond two-dimensional cultures, 3D brain organoids recapitulate more complex features of human neurodevelopment, including progenitor proliferation, neuronal migration, and cortical layer formation [7]. These systems are particularly valuable for modeling malformations of cortical development, which often present with microcephaly, disorganized cytoarchitecture, and severe cognitive impairments [7]. Recent advances include the generation of dorsal-ventral assembloids by fusing region-specific organoids, which model the migration of interneurons from ventral to dorsal regions—a process critical for establishing balanced cortical circuitry [4]. These assembloid systems have revealed that late-born interneurons arrange into chain-like structures surrounded by astrocytes, essentially recapitulating postnatal migratory streams observed in human infants [4].

Table 2: Quantitative Proteomic and Phosphoproteomic Landscape During Neural Specification

| Molecular Category | hPSCs | hNSCs | Key Regulated Components | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Proteins Identified [10] | ~13,000 | ~13,000 | Transcription factors, epigenetic regulators | Comprehensive mapping of proteome dynamics |

| Phosphorylation Sites [10] | ~60,000 | ~60,000 | Kinase substrates, signaling nodes | Insight into post-translational regulation |

| Neural Induction Markers | - | - | PAX6, NESTIN, OTX2 | Confirmation of neural lineage commitment |

| Pluripotency Factors | - | - | OCT4, NANOG, SOX2 | Downregulated during specification |

| Validated Regulators | - | - | Midkine (MDK) | Novel secreted factor promoting neuralization |

Applications in Neurodevelopmental Disorder Research

Disease Modeling and Mechanistic Insights

iPSC-derived neural models have become indispensable tools for elucidating the pathophysiology of NDDs. In idiopathic autism spectrum disorder (ASD), iPSC-derived neurons exhibit functional alterations including reduced calcium transients, impaired synaptic neurotransmission, and decreased network connectivity [11]. Molecular profiling of ASD-derived neuronal progenitor cells (NPCs) has identified differentially expressed microRNAs (hsa-let-7e-5p, hsa-miR-135b-5p, hsa-miR-16-5p, and hsa-miR-27b-3p) that cluster in pathways regulating neurogenesis, neuronal functioning, and cAMP/Ca2+ signaling [11]. For monogenic disorders like Tuberous Sclerosis Complex (TSC), iPSC-derived neurons have revealed dysregulation of the mTOR signaling pathway and neuronal hyperexcitability that can be rescued by mTORC1-selective inhibitors [7]. Similarly, iPSC models of epilepsy generated from patients with CLCNKB mutations have uncovered differentially expressed gene networks implicated in epileptogenesis through transcriptomic profiling [7].

High-Content Screening and Therapeutic Development

The integration of iPSC-derived neural models with functional phenotyping platforms enables sophisticated screening applications for NDD research. Multielectrode arrays, calcium imaging, and high-content imaging can capture disease-relevant phenotypes at scale [7]. When combined with machine learning approaches, these rich functional datasets can classify subtle phenotypic signatures, accelerate drug screening, and improve disease modeling in both 2D cultures and 3D organoids [7]. For example, chemogenetic approaches using Designer Receptors Exclusively Activated by Designer Drugs (DREADDs) in co-cultures of human iPSC-derived neurons and rat cortical neurons have demonstrated impaired synaptic connectivity in ASD models [11]. These platforms provide valuable tools for evaluating potential therapeutic compounds in human-relevant systems before advancing to clinical trials.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Neural Reprogramming and Differentiation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Protocol | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, MYC (OSKM) [3]; OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, LIN28 [3] | Induction of pluripotency in somatic cells | iPSC generation from patient fibroblasts or blood cells |

| Neural Induction Molecules | Dorsomorphin, A83-01, SB431542, LDN193189 [10] | SMAD inhibition to promote neural ectoderm formation | Initial neural specification from iPSCs |

| Neural Progenitor Markers | Antibodies against PAX6, NESTIN, SOX1 [10] | Identification and sorting of neural stem cells | Quality control of neural differentiation |

| Neuronal Maturation Factors | BDNF, GDNF, NT-3, cAMP, Ascorbic Acid [11] | Promotion of neuronal survival, maturation, and synaptic development | Terminal differentiation of neurons from NPCs |

| Functional Assay Reagents | GCaMP6s calcium indicator [11], DREADDs [11] | Measurement of neuronal activity and network connectivity | Functional characterization of neuronal models |

Visualizing Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Core Signaling Pathways in Neural Specification

Experimental Workflow for NDD Modeling

The integration of somatic cell reprogramming with neural differentiation technologies has created unprecedented opportunities for modeling neurodevelopmental disorders in a human-specific context. The core principles outlined in this guide—from the initial reprogramming of somatic cells using defined factors to the precise specification of neural lineages through controlled manipulation of developmental signaling pathways—provide a robust framework for investigating disease mechanisms. Current challenges include the standardization of differentiation protocols across laboratories, improvement of functional maturation in iPSC-derived neurons, and meaningful integration of multi-omics datasets [7]. Future advances will likely focus on enhancing the complexity and reproducibility of 3D model systems, incorporating non-neural cell types such as microglia and vascular cells, and developing more sophisticated functional readouts that capture network-level perturbations in NDDs. As these technologies continue to evolve, they promise to bridge the gap between cellular models and clinical applications, ultimately enabling the development of targeted interventions for neurodevelopmental disorders.

The advent of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology has ushered in a transformative era for biomedical research, particularly in the study of complex neurodevelopmental disorders. By enabling the reprogramming of adult somatic cells back to a pluripotent state, this technology provides an unprecedented window into human development and disease. The core advantages of patient-specific modeling, preservation of the complete genetic background, and the capacity for unlimited expansion collectively address long-standing limitations of traditional model systems. These properties make iPSCs an indispensable tool for deconstructing the pathogenic mechanisms of neurodevelopmental conditions, which are often influenced by a complex interplay of polygenic and environmental factors that are uniquely human and difficult to recapitulate in animal models [11] [3] [12].

The foundational discovery by Shinya Yamanaka and colleagues, which showed that the forced expression of four transcription factors (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc) could revert specialized cells to pluripotency, earned them the Nobel Prize in 2012 and established the technical basis for this field [13] [3] [14]. The subsequent refinement of this technology has been driven by the need to create clinically relevant human cellular models that faithfully capture the genetic complexity of individual patients, thereby facilitating a new generation of mechanistic studies and therapeutic discovery efforts [15].

Patient-Specific Modeling of Neurodevelopmental Disorders

Patient-specific modeling stands as a cornerstone advantage of iPSC technology. This approach allows researchers to derive pluripotent stem cells directly from individuals with neurodevelopmental disorders, which can then be differentiated into the specific neural cell types affected in the disease. This process creates a genetically tailored in vitro model system that recapitulates key aspects of the patient's neurobiology.

Applications in Idiopathic and Syndromic Disorders

This capability is particularly powerful for studying idiopathic diseases—those with unknown or complex etiology—where the genetic drivers are not fully understood. For example, in Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), a condition characterized by extensive heterogeneity, iPSCs derived from patients with clinically homogeneous presentations have revealed functional alterations in the resulting neurons. These include less frequent calcium transients and impaired synaptic neurotransmission compared to neurons derived from control individuals, providing a measurable cellular phenotype for a behaviorally defined disorder [11]. Similarly, in schizophrenia (SCZ), another polygenic neurodevelopmental condition, iPSC-derived oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs) and oligodendrocytes (OLs) from patients have shown morphological alterations, including significantly increased branch length and junction number in mature oligodendrocytes, pointing to a cell-autonomous, genetically driven deficit in the oligodendroglial lineage that may underlie the white matter disturbances observed in patients [12].

Table 1: Summary of Functional Phenotypes in Patient-Specific iPSC-Derived Neural Cells

| Neurodevelopmental Disorder | iPSC-Derived Cell Type | Key Functional Phenotypes Identified | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) | Cortical Neurons | ↓ Spontaneous calcium transients; ↓ Synaptic neurotransmission and connectivity; Dysregulated glutamate signaling | [11] |

| Schizophrenia (SCZ) | Oligodendrocytes (OLs) | ↑ Branch length; ↑ Junction number; Dysregulated cell signaling and proliferation | [12] |

Experimental Workflow for Patient-Specific Modeling

The standard workflow for establishing a patient-specific disease model involves several critical steps, each requiring rigorous quality control to ensure the resulting cellular models are accurate and reproducible.

Figure 1: Workflow for patient-specific iPSC modeling of neurodevelopmental disorders.

Preservation of the Native Genetic Background

A paramount strength of iPSC-based models is their ability to preserve the entire and unique genetic blueprint of the donor individual. Unlike other model systems that may introduce confounding genetic variables, iPSCs retain the patient's specific combination of common variants, rare mutations, and structural polymorphisms that collectively contribute to disease susceptibility and manifestation.

Capturing Polygenic Risk in a Dish

Neurodevelopmental disorders like ASD, SCZ, and intellectual disability are highly polygenic. This means that an individual's risk is determined by the combined effect of hundreds or thousands of genetic variants, each with a small individual effect. iPSC models inherently capture this complex genetic architecture. Gene-set enrichment analyses using transcriptomic data from iPSC-derived neural cells have confirmed that the genetic associations identified from large-scale genome-wide association studies (GWAS) for schizophrenia are indeed enriched in the transcriptional signatures of these relevant cell types [12]. This provides a direct biological bridge between statistical genetic findings and functional cellular pathophysiology, allowing researchers to study how a patient's complete set of risk genes orchestrates molecular and functional changes in the brain.

A Platform for Genetic Manipulation

Furthermore, while preserving the native genetic background is crucial for observational studies, the isogenic nature of iPSCs also makes them an ideal platform for targeted genetic manipulation. Using gene-editing tools like CRISPR-Cas9, researchers can introduce or correct specific risk variants in patient-derived iPSC lines. By comparing the edited line to its original parent line, scientists can isolate the phenotypic consequences of a single genetic change against a constant genetic background. This powerful approach allows for the direct demonstration of causality for specific genetic variants identified in patients with neurodevelopmental conditions [13] [3].

Unlimited Expansion Capacity for Research and Screening

The capacity for virtually unlimited self-renewal is a defining property of iPSCs, which has profound practical implications for biomedical research. This characteristic ensures a continuous and scalable supply of biological material, overcoming a major bottleneck that has historically plagued neuroscience: the inability to access living, disease-relevant human brain cells.

Enabling High-Throughput and Reproducible Science

The unlimited expansion potential of iPSCs enables the generation of the large cell numbers required for high-throughput drug screening campaigns, multi-omics studies (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics), and the development of complex co-culture systems and organoids [13] [3]. This scalability is essential for achieving the statistical power needed to study highly variable human biological systems. Moreover, by creating a master cell bank of a single patient-derived iPSC line, researchers across different labs can perform experiments on a genetically identical, renewable resource, dramatically improving the reproducibility and reliability of findings in neurodevelopmental disease research [16].

Table 2: Applications Enabled by the Unlimited Expansion of iPSCs

| Application | Description | Benefit for Neurodevelopmental Research |

|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Drug Screening | Testing thousands of small molecules for their ability to reverse cellular phenotypes. | Identifies candidate therapeutics for disorders with no effective medication, e.g., for core symptoms of ASD or SCZ. |

| 'Clinical Trial in a Dish' | Using panels of patient-derived cells to predict variable drug responses. | Personalizes medicine approaches for neurodevelopmental disorders. |

| Multi-omics Profiling | Comprehensive molecular characterization using sequencing and mass spectrometry. | Reveals disease-associated pathways (e.g., synaptic, mTOR, Wnt) from the same biological source. |

| Complex 3D Model Generation | Creating cerebral organoids and assembloids. | Models neural circuit formation and inter-cell-type dysfunction. |

Technical Considerations for Scalable Production

To leverage this advantage for industrial and clinical translation, scalable production processes are being developed. These advanced bioprocessing systems are designed to maintain the integrity of these sensitive cells during large-scale expansion. Studies have demonstrated that integrated systems using low-shear bioreactors and closed, automated cell processing can achieve high cell recovery rates (>90%) and maintain high viability (>95%) and pluripotency marker expression over multiple serial passages, which is critical for generating the quantities of cells needed for robust research and future therapies [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for iPSC-Based Research

The successful application of iPSC technology relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools, each designed to maintain, differentiate, and characterize pluripotent stem cells and their neuronal progeny.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for iPSC Modeling of Neurodevelopmental Disorders

| Reagent/Category | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors (OSKM/OSNL) | Core transcription factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC or NANOG, LIN28) that initiate reprogramming. | Initial generation of iPSCs from patient somatic cells. |

| Non-Integrating Delivery Vectors | Methods to deliver factors without altering the host genome (e.g., Sendai virus, episomal plasmids, mRNA). | Clinical-grade iPSC generation with enhanced safety profiles. |

| Chemically Defined Media (e.g., mTeSR1, E8) | Standardized, xeno-free nutrient media to support iPSC self-renewal and maintain pluripotency. | Feeder-free culture; maintenance of genomic stability during expansion. |

| Extracellular Matrix Coatings (e.g., Matrigel, Laminin-521) | Surrogate substrate for cell adhesion and signaling, replacing mouse feeder cells. | Feeder-free culture systems that enhance reproducibility. |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors/Activators | Direct differentiation toward specific neural fates (e.g., SMAD, TGF-β, Wnt pathway inhibitors). | Highly efficient generation of cortical neurons, oligodendrocytes, etc. |

| Pluripotency Validation Markers | Antibodies for flow cytometry/immunocytochemistry (e.g., OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, SSEA-4). | Quality control to confirm the pluripotent state of iPSC banks. |

| Genetic Engineering Tools (e.g., CRISPR-Cas9) | For creating isogenic controls or introducing disease-associated mutations. | Establishing causal links between genetic variants and cellular phenotypes. |

Signaling Pathways in Neurodevelopment and Disease

The directed differentiation of iPSCs into specific neural lineages is guided by the sequential activation and inhibition of key evolutionarily conserved signaling pathways. Furthermore, dysregulation of these same pathways is frequently implicated in the pathophysiology of neurodevelopmental disorders.

Figure 2: Key signaling pathways studied in iPSC models of neurodevelopment. Pathways (yellow) govern critical functions (green), and their dysregulation is linked to disorders (red).

The synergistic advantages of patient-specific modeling, genetic background preservation, and unlimited expansion establish iPSC technology as a uniquely powerful platform for deconstructing the complex mechanisms underlying neurodevelopmental disorders. By providing a renewable source of patient-derived neural cells, this technology enables researchers to move beyond correlation to causation, linking genetic findings from GWAS to functional cellular and molecular phenotypes in a human context. As differentiation protocols become more sophisticated, yielding increasingly complex neural assemblies and organoids, and as scalable manufacturing processes improve, the fidelity and utility of these models will only increase. The continued application of iPSC-based models promises to accelerate the identification of novel therapeutic targets and the development of personalized interventions for individuals with neurodevelopmental conditions.

The study of neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs) has been fundamentally transformed by the advent of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology. This revolutionary approach enables researchers to generate patient-specific neural cells, providing unprecedented access to the cellular and molecular underpinnings of complex neurodevelopmental conditions. NDDs—including autism spectrum disorder (ASD), schizophrenia, and rare genetic syndromes—share common obstacles in research: limited access to functional human brain tissue, species-specific limitations of animal models, and profound genetic and clinical heterogeneity [17] [18]. iPSC technology effectively bypasses these constraints by allowing the reprogramming of patient somatic cells into pluripotent stem cells, which can subsequently be differentiated into disease-relevant neural cell types, including various neuronal subtypes, astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and microglia [17] [3].

The application of iPSC models has been particularly valuable for disorders affecting the central nervous system, given the ethical limitations of working with human embryonic stem cells and the inability to sustainably maintain primary neural cultures [17]. Furthermore, iPSCs retain the complete genetic background of the donor, enabling researchers to investigate the complex interactions between genetic risk factors and environmental influences in NDD pathogenesis [17] [19]. The versatility of iPSC technology extends beyond simple two-dimensional (2D) monocultures to increasingly complex three-dimensional (3D) organoid systems that more faithfully recapitulate the architecture and cellular diversity of the developing human brain [17] [18]. This technical advancement has opened new avenues for elucidating disease mechanisms, identifying novel therapeutic targets, performing high-throughput drug screening, and developing personalized treatment approaches for NDDs [17] [3].

iPSC Modeling of Autism Spectrum Disorders

Autism spectrum disorder represents a group of complex neurodevelopmental conditions characterized by persistent deficits in social communication and interaction, alongside restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities [17]. The etiopathogenesis of ASD is multifactorial, involving complex interactions between genetic and environmental factors, with heritability estimates ranging from 50% to 90% based on family and twin studies [17]. iPSC-based models have provided crucial insights into both syndromic (associated with known genetic conditions) and non-syndromic (idiopathic) forms of ASD by enabling the investigation of pathological mechanisms in disease-relevant human cell types [17] [19].

Key Cellular Phenotypes in ASD iPSC Models

Research using iPSC-derived neural progenitor cells (NPCs) from individuals with ASD and macrocephaly has revealed increased cellular proliferation resulting from alterations in a canonical Wnt-β-catenin/BRN transcriptional cascade [17]. These abnormalities in proliferation lead to aberrant neurogenesis and reduced synaptogenesis, ultimately contributing to functional defects in neuronal networks [17]. Similar hyperproliferation phenotypes have been observed in NPCs derived from individuals with syndromic forms of ASD, including Rett syndrome (RTT), Fragile X syndrome (FXS), tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), Phelan-McDermid syndrome (PMDS), and Timothy syndrome (TS) [17].

In addition to proliferation defects, iPSC-derived neurons from ASD patients have demonstrated various synaptic abnormalities and electrophysiological alterations. These include impaired neurite outgrowth, aberrant synaptogenesis, and network hyperexcitability, which may underlie the behavioral manifestations observed in ASD [17] [19]. The ability to recapitulate these core cellular phenotypes in vitro has positioned iPSC technology as a powerful platform for identifying potential therapeutic interventions and conducting drug screening campaigns.

ASD Modeling Table

Table 1: Summary of Key Findings from iPSC-Based Studies of Autism Spectrum Disorders

| Disorder Category | Specific Disorder/Model | Key Cellular Phenotypes | Molecular Pathways Involved |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-syndromic ASD | ASD with macrocephaly | NPC hyperproliferation, aberrant neurogenesis, reduced synaptogenesis | Wnt-β-catenin/BRN transcriptional cascade [17] |

| Syndromic ASD | Rett Syndrome (RTT) | NPC dysfunction, synaptic deficits, network abnormalities | MECP2 mutations, chromatin remodeling [17] |

| Fragile X Syndrome (FXS) | NPC hyperproliferation, aberrant neurite outgrowth, mGluR signaling defects | FMR1 silencing, mGluR pathway, AMPA receptor trafficking [17] [20] | |

| Tuberous Sclerosis Complex (TSC) | NPC hyperproliferation, neuronal hyperexcitability, dysregulated growth | mTOR signaling pathway [17] [18] | |

| Phelan-McDermid Syndrome (PMDS) | NPC dysfunction, synaptic deficits | SHANK3 mutations, synaptic scaffolding [17] | |

| Timothy Syndrome (TS) | NPC dysfunction, calcium signaling defects | CACNA1C mutations, calcium signaling [17] |

Elucidating Schizophrenia Mechanisms Through iPSC Models

While the search results provided limited specific information on schizophrenia modeling, the general principles of iPSC-based NDD research apply to this complex neuropsychiatric disorder. Schizophrenia is understood to have a significant neurodevelopmental component, with genetic and environmental factors interacting during critical periods of brain development to increase vulnerability to the disorder. iPSC models derived from patients with schizophrenia would likely focus on key processes such as neuronal migration, cortical patterning, synaptic formation and function, and the balance between excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission.

The integration of iPSC technology with genomic approaches would be particularly valuable for schizophrenia research, given the polygenic nature of the disorder and the identification of numerous risk variants through genome-wide association studies. Isogenic lines generated using CRISPR/Cas9 technology could help determine the functional consequences of specific risk alleles in a controlled genetic background. Furthermore, the application of 3D brain organoid models could provide insights into potential cortical maldevelopment and disrupted cell positioning that may contribute to schizophrenia pathogenesis.

Rare Genetic Neurodevelopmental Syndromes

iPSC technology has proven particularly transformative for studying rare neurodevelopmental disorders, where the scarcity of patients, lack of neural tissues for analysis, and absence of representative animal models have historically hampered research progress [20]. These disorders, while individually rare, collectively affect a substantial proportion of the world's population and often present with severe neurological symptoms [20].

Fragile X Syndrome (FXS)

Fragile X syndrome represents the most common inherited form of intellectual disability and a frequent monogenic cause of ASD [20]. FXS results from an expansion of CGG repeats (>200 repeats) in the 5'-untranslated region of the FMR1 gene, leading to epigenetic silencing and loss of fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP) [20]. iPSCs generated from FXS patients (FXS-iPSCs) maintain the hypermethylated, transcriptionally inactive state of the FMR1 gene, unlike embryonic stem cells where FMR1 downregulation occurs only during differentiation [20].

Neurons derived from FXS-iPSCs display aberrant differentiation characterized by defective neurite outgrowth, with impairments in both initiation and extension processes [20]. This suggests that normal FMRP expression is critical for early neurodevelopmental events preceding synaptogenesis. Additionally, NPCs derived from FXS-iPSCs show altered metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR) signaling, resulting in increased calcium influx and impaired differentiation [20]. Importantly, CRISPR/Cas9-mediated removal of CGG repeats or treatment with chromatin remodeling agents has demonstrated that the epigenetic silencing of FMR1 is reversible, with restoration of FMRP expression and rescue of neuronal differentiation abnormalities [20].

Rett Syndrome (RTT)

Rett syndrome is an X-linked neurodevelopmental disorder primarily affecting females, characterized by apparently normal early development followed by regression, loss of purposeful hand skills, gait abnormalities, and stereotypic hand movements [20]. RTT is predominantly caused by mutations in the MECP2 gene, which encodes methyl-CpG-binding protein 2, a critical regulator of gene expression and chromatin architecture. iPSC-derived neurons from RTT patients have revealed defects in neuronal maturation, synaptic density, and electrophysiological properties, providing insights into the consequences of MECP2 dysfunction in human neurons [17] [20].

Tuberous Sclerosis Complex (TSC)

Tuberous sclerosis complex is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by benign tumors in multiple organs, including the brain, where it is associated with epilepsy, intellectual disability, and ASD features [18]. TSC results from mutations in either TSC1 or TSC2 genes, leading to constitutive activation of the mTOR signaling pathway. iPSC-derived neurons from TSC patients have demonstrated neuronal hyperexcitability and abnormal morphology, phenotypes that can be rescued by mTORC1-selective inhibitors [18]. These findings highlight the utility of iPSC models not only for understanding disease mechanisms but also for preclinical drug testing and therapeutic development.

Rare NDD Modeling Table

Table 2: Summary of iPSC-Based Studies of Rare Neurodevelopmental Disorders

| Rare NDD | Genetic Cause | Key iPSC-Derived Phenotypes | Therapeutic Insights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fragile X Syndrome | FMR1 CGG repeat expansion (>200) | FMR1 hypermethylation, defective neurite outgrowth, altered mGluR signaling, increased calcium influx in NPCs [20] | CRISPR/Cas9-mediated CGG excision restores FMRP; chromatin remodeling agents reverse silencing [20] |

| Rett Syndrome | MECP2 mutations | NPC dysfunction, defects in neuronal maturation, reduced synaptic density, electrophysiological abnormalities [17] [20] | - |

| Tuberous Sclerosis Complex | TSC1 or TSC2 mutations | NPC hyperproliferation, neuronal hyperexcitability, abnormal morphology [17] [18] | mTORC1-selective inhibitors rescue hyperexcitability and morphological defects [18] |

| Phelan-McDermid Syndrome | SHANK3 mutations | NPC dysfunction, synaptic deficits | - |

| Timothy Syndrome | CACNA1C mutations | NPC dysfunction, calcium signaling defects | - |

Technical Methodologies in iPSC-Based NDD Research

iPSC Generation and Neural Differentiation

The fundamental process of generating iPSCs involves reprogramming somatic cells (typically fibroblasts or blood cells) through the expression of specific transcription factors. The original reprogramming factors—OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC (OSKM)—remain widely used, although alternative combinations such as OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, and LIN28 have also been employed successfully [3]. Following iPSC generation and characterization, several strategies exist for differentiating these pluripotent cells into neural lineages.

The two main approaches for generating neural cells from iPSCs include direct differentiation and reprogramming. In direct differentiation, iPSCs are first induced to form neural progenitor cells (NPCs) through dual SMAD inhibition, followed by exposure to specific trophic factors (e.g., cAMP, BDNF, NT3, and GDNF) to promote terminal differentiation into specific neuronal subtypes [17]. Alternatively, reprogramming strategies involve direct conversion using lentiviral delivery of neural-specific transcription factors coupled with antibiotic selection cassettes for efficient conversion and purification [17]. Each method presents distinct advantages and limitations, with the choice often depending on laboratory preference, desired neuronal subtype, and specific application requirements.

2D vs. 3D Modeling Approaches

Traditional iPSC-based disease modeling has relied primarily on two-dimensional (2D) monolayer cultures, which have proven valuable for investigating cell-autonomous phenotypes, high-content imaging, and electrophysiological characterization [17]. However, the recognition that human pathologies originate within the context of complex tissue environments has driven the development of three-dimensional (3D) brain organoid models [17] [18].

Brain organoids are self-organizing 3D aggregates derived from iPSCs that contain multiple neural cell types and develop cerebral-like structures, more closely mimicking the in vivo human brain microenvironment and pathophysiology [17]. These 3D models have been particularly informative for studying disorders involving cortical maldevelopment, disruptions in neuronal migration, and altered cell positioning, as they recapitulate important aspects of early developmental processes such as progenitor proliferation, neuronal migration, and layer formation [18]. The integration of 3D organoids with multi-omics approaches and advanced functional assays represents the cutting edge of iPSC-based NDD research.

Experimental Workflow Diagram

Diagram 1: Experimental Workflow for iPSC-Based NDD Research

Successful iPSC-based modeling of NDDs requires carefully selected reagents and methodologies. The table below outlines key resources essential for conducting robust iPSC studies in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for iPSC-Based NDD Modeling

| Category | Specific Reagents/Tools | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC (OSKM) or OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, LIN28 | Somatic cell reprogramming to pluripotency | Delivery via integrating (lentivirus) or non-integrating (episomal, mRNA) methods [3] |

| Neural Induction | Dual SMAD inhibitors (SB431542, LDN193189) | Efficient neural induction from iPSCs | Standard approach for NPC generation [17] |

| Neural Differentiation | BDNF, GDNF, NT3, cAMP | Terminal differentiation of NPCs into mature neurons | Concentration and timing vary by neuronal subtype [17] |

| Gene Editing | CRISPR/Cas9 systems, TALENs, ZFNs | Generation of isogenic controls; disease modeling of specific mutations | CRISPR/Cas9 most widely used for efficient genome engineering [20] |

| Characterization Antibodies | SSEA4, Tra-1-60, OCT3/4 (pluripotency); TUJ1, MAP2, NeuN (neuronal) | Validation of pluripotent state and neural differentiation | Essential for quality control throughout differentiation process [21] |

| Functional Assays | Multi-electrode arrays, calcium imaging, patch clamp | Electrophysiological characterization of neuronal function | Critical for assessing functional phenotypes in NDD models [18] |

Signaling Pathways in Neurodevelopmental Disorders

iPSC-based studies have identified several key signaling pathways that are commonly disrupted across multiple NDDs. The diagram below illustrates some of these critical pathways and their interconnections.

Diagram 2: Key Signaling Pathways in Neurodevelopmental Disorders

iPSC technology has fundamentally transformed our approach to studying neurodevelopmental disorders, providing unprecedented access to patient-specific neural cells and enabling mechanistic insights that were previously inaccessible. The applications spanning autism spectrum disorder, schizophrenia, and rare genetic syndromes demonstrate the remarkable versatility of this platform for both basic research and therapeutic development. The integration of iPSC-derived models with advanced functional assays, multi-omics approaches, and computational analytics represents the current frontier in NDD research [18].

Despite substantial progress, challenges remain in standardizing differentiation protocols, improving reproducibility across laboratories, and effectively integrating the massive multi-layered datasets generated by these sophisticated models [18]. Furthermore, translating findings from cellular models into clinical interventions will require close collaboration between basic scientists, clinicians, and computational experts. Nevertheless, the trajectory is clear: by uniting stem cell biology, multi-omics integration, and computational frameworks, the field is moving toward more predictive, patient-specific, and ultimately actionable models of neurodevelopmental disorders. The continued refinement of iPSC-based technologies holds exceptional promise for unraveling the complex etiology of NDDs and developing effective targeted therapies for these debilitating conditions.

Advanced iPSC Methodologies: From 2D Cultures to 4D Multi-Organ Systems for Neural Research

The study of human neurodevelopmental disorders has long been constrained by the limited availability of authentic human tissue models that accurately recapitulate the complexity of the developing brain. Traditional two-dimensional (2D) monolayer cultures, while valuable for specific applications, fail to capture the three-dimensional architecture and cell-cell interactions inherent to native neural tissue. The advent of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology has revolutionized this landscape, enabling the derivation of patient-specific neural cells and the development of increasingly sophisticated three-dimensional (3D) model systems [3]. These advances have been particularly transformative for researching neurodevelopmental disorder mechanisms, as they provide unprecedented access to human-specific developmental processes and disease phenotypes that are often not faithfully reproduced in animal models [18].

The progression from 2D monolayers to 3D organoids and recently to assembloids represents a paradigm shift in how researchers model the intricate cellular relationships and spatial organization critical to understanding brain development and dysfunction. Organoids are defined as 3D structures derived from stem cells that self-organize through cell sorting and spatially restricted lineage commitment, recapitulating aspects of the developing organ [22]. Assembloids represent a further advancement, created by facing regionally specified organoids to model interactions between different brain areas or cell types [4]. This evolution in model systems has created new opportunities to dissect the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying neurodevelopmental disorders, leveraging the genetic background of patients while overcoming the limitations of earlier modeling approaches.

Technical Foundations and Methodological Approaches

iPSC Generation and Neural Differentiation

The foundation of all modern human neural tissue models begins with the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). Since the groundbreaking work of Takahashi and Yamanaka in 2006, iPSC technology has matured significantly, with numerous refinements in reprogramming methods, factor delivery, and somatic cell source selection [3] [23]. Current approaches prioritize non-integrating delivery methods such as Sendai virus, episomal plasmids, or mRNA transfection to minimize genomic alteration risks while maintaining high reprogramming efficiency [23]. The selection of somatic cell sources has expanded beyond the original dermal fibroblasts to include more accessible options such as peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and renal epithelial cells from urine, facilitating the creation of patient-specific models from diverse clinical populations [23].

The differentiation of iPSCs into neural lineages typically employs dual SMAD inhibition to direct cells toward a neural fate, followed by region-specific patterning factors that generate distinct neuronal subtypes [24]. For cortical excitatory neurons, this involves activation of Wnt and FGF signaling, while ventral forebrain identities (including interneurons) require SHH activation. The efficiency and reproducibility of these differentiation protocols have improved substantially, enabling the generation of highly enriched populations of specific neuronal subtypes, though heterogeneity remains a challenge, particularly in more complex 3D systems [23].

2D Monolayer Culture Systems

Two-dimensional monolayer cultures represent the most reductionist approach to modeling neural tissues in vitro. In these systems, iPSCs are differentiated into neural progenitor cells (NPCs) and subsequently into neurons or glia on flat, coated surfaces, typically in the presence of specific patterning factors. The methodology involves several sequential steps: initial neural induction via dual SMAD inhibition, regional patterning using small molecules or growth factors, terminal differentiation through neurotrophic factor withdrawal, and finally functional maturation over several weeks [23].

The key advantage of 2D systems lies in their simplicity, reproducibility, and scalability, making them ideal for high-throughput screening applications and reductionist experimental designs. However, this simplicity comes with significant limitations, as 2D cultures lack the complex cytoarchitecture, cell-cell interactions, and microenvironmental cues present in the developing brain [25] [22]. Studies comparing transcriptomic profiles between 2D monolayers and 3D organoids have revealed profound differences in gene expression patterns, with monolayers exhibiting suppressed Notch signaling and altered radial glia polarity that ultimately impairs the generation of intermediate progenitors and cortical neurons [25].

3D Organoid Culture Systems

Three-dimensional organoid cultures represent a significant advancement in neural tissue modeling by recapitulating aspects of the brain's spatial organization and developmental processes. Cerebral organoids can be generated through multiple approaches, including unguided methods that rely on intrinsic self-organization capacity and guided protocols that use exogenous patterning factors to generate region-specific organoids [26]. The basic protocol involves forming embryoid bodies from iPSCs, inducing neural differentiation, embedding these structures in extracellular matrix (typically Matrigel), and maintaining them in spinning bioreactors or orbital shakers to enhance nutrient and oxygen exchange [26] [22].

Organoid cultures model several key aspects of human brain development, including the emergence of ventricular zones, the generation of diverse neuronal subtypes, and the formation of layered cortical structures. The self-organization capacity of organoids arises from cell sorting and spatially restricted lineage commitment, processes that mimic in vivo development [22]. However, organoids face challenges including necrotic core formation due to limited nutrient diffusion, heterogeneity in size and cellular composition, and incomplete representation of later developmental stages [26]. Recent advances have addressed some limitations through the incorporation of microfluidic systems to improve vascularization, enhanced patterning protocols for more reproducible regional specification, and extended culture durations to capture later developmental events [4] [26].

Assembloid Culture Systems

Assembloids represent the most advanced in vitro model for neural tissues, created by fusing regionally specified organoids to study interactions between different brain areas or cell types. This approach enables researchers to model long-distance migration, circuit formation, and interactions between distinct neuronal populations that cannot be captured in single organoids [4]. A representative protocol involves generating dorsal (cortical) and ventral (ganglionic eminence) organoids separately using specific patterning factors, then bringing them together at a defined developmental stage to form assembloids, with subsequent analysis of interneuron migration and integration [4].

The assembloid platform has enabled groundbreaking studies of human-specific developmental processes, such as the prolonged migration of interneurons that continues into the postnatal period in humans. Recent work has demonstrated that after extended culture (over 200 days), newly born migratory interneurons in assembloids arrange themselves into connected chains surrounded by astrocytes, essentially recapitulating the architectural and migratory patterns observed in early postnatal human brains [4]. This model system provides unprecedented opportunities to study cellular interactions in a human-specific context, particularly for neurodevelopmental disorders involving aberrant migration or circuit formation.

Comparative Analysis of Model Systems

Architectural and Cellular Complexity

The architectural fidelity of neural tissue models profoundly influences their cellular composition and developmental potential. Comparative studies between 2D monolayers and 3D organoids have revealed striking differences in their cellular organization and differentiation capacity.

Table 1: Architectural and Cellular Features of Neural Tissue Models

| Feature | 2D Monolayers | 3D Organoids | Assembloids |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Organization | Flat, uniform structure | Self-organized 3D structures with regional zones | Multiple integrated regions with interface zones |

| Cell-Cell Interactions | Limited to horizontal plane | Multi-directional, including apical-basal polarity | Cross-regional interactions and long-distance migration |

| Radial Glia Polarity | Altered, disrupted polarity | Preserved apical-basal polarity with ventricular zones | Preserved polarity across multiple regions |

| Neuronal Differentiation | Impaired generation of intermediate progenitors and cortical neurons | Sequential generation of deep and upper layer neurons | Region-specific neuronal subtypes with functional connectivity |

| Glial Populations | Limited astrocyte and microglia incorporation | Astrocytes present, microglia often missing | Multiple glial types supporting neuronal migration and function |

| Vascularization | Absent | Absent, leading to necrotic cores | Limited, but improved nutrient exchange at interfaces |

Research by Scuderi et al. directly comparing 2D monolayers and 3D organoids demonstrated that organoids exhibit more efficient Notch signaling in ventricular radial glia due to preserved cell adhesion, resulting in subsequent generation of intermediate progenitors and outer radial glia in a sequence that better recapitulates cortical development [25]. Network analyses revealed co-clustering of cell adhesion and Notch-related transcripts in a module strongly downregulated in monolayers, providing a molecular explanation for their limited differentiation capacity [25].

Assembloids further enhance this architectural complexity by modeling interactions between different brain regions. For example, dorsal-ventral assembloids have revealed that chain migration of interneurons requires both intrinsic cues from late-born interneurons and specific interactions with surrounding astrocytes [4]. This level of cellular crosstalk cannot be modeled in simpler systems and provides critical insights into human-specific developmental processes that may be disrupted in neurodevelopmental disorders.

Physiological and Functional Properties

The functional properties of neurons and neural circuits differ significantly across model systems, with important implications for their utility in disease modeling and drug screening.

Table 2: Functional Properties of Neural Tissue Models

| Property | 2D Monolayers | 3D Organoids | Assembloids |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neural Activity | Synchronized bursting; limited network complexity | Spontaneous, synchronized network activity with complex bursting patterns | Cross-regional synchronized activity; developing circuit dynamics |

| Synaptic Development | Immature synapses; limited pruning | Maturing synapses with spontaneous pruning | Region-specific synaptic properties; functional connectivity between regions |

| Circuit Formation | Limited local connectivity | Local microcircuits with layered organization | Long-range connections between different regions |

| Metabolic Characteristics | Uniform nutrient and oxygen access | Gradient-dependent metabolism with hypoxic cores | Improved metabolic support at interfaces |

| Response to Stimulation | Homogeneous response to pharmacological agents | Stratified responses based on spatial position | Region-specific responses to modulators |

| Disease Modeling Fidelity | Limited to cell-autonomous phenotypes | Captures some tissue-level pathologies | Models non-cell-autonomous mechanisms and circuit-level defects |

3D culture systems more closely resemble the architectural and functional properties of in vivo tissues, with cells exposed to different concentrations of nutrients, growth factors, and oxygen depending on their localization [22]. This spatial heterogeneity creates microenvironments that influence cellular phenotypes, including differential responses to pharmacological agents that may explain discrepancies between traditional drug screening results and clinical outcomes [22]. For instance, studies have demonstrated that temozolomide resistance in glioblastoma 3D cultures was 50% higher than in 2D models, highlighting the importance of microenvironmental context for therapeutic response [22].

Functional analyses of 3D neurospheres have revealed reliable spontaneous activity that offers functional tissue culture readouts of neural firing, including oscillatory network activity that becomes more complex with maturation [24]. Assembloids exhibit even more sophisticated functional properties, with emerging evidence of coordinated activity between fused regions that begins to approximate developing neural circuits in the human brain [4].

Experimental Utility and Limitations

Each model system offers distinct advantages and limitations for specific research applications in neurodevelopmental disorders.

Table 3: Experimental Applications of Neural Tissue Models

| Application | 2D Monolayers | 3D Organoids | Assembloids |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Screening | Excellent for scalability and reproducibility | Moderate throughput with emerging platforms | Low throughput, technically challenging |

| Genetic Manipulation | Highly efficient via viral transduction or CRISPR | Moderate efficiency with improved techniques | Limited to pre-fusion manipulation or viral delivery |

| Live Imaging | Straightforward with full optical access | Challenging due to opacity and depth | Complex, requiring specialized microscopy |

| Transcriptomic Analysis | Homogeneous cell populations | Heterogeneous populations requiring spatial methods | Extreme heterogeneity with regional identities |

| Disease Modeling Scope | Cell-autonomous mechanisms | Tissue-level phenotypes and cell non-autonomous effects | Circuit-level disorders and long-range interactions |

| Reproducibility | High consistency across experiments | Moderate, with batch-to-batch variability | Lower, with fusion efficiency variations |

| Developmental Timeframe | Limited to early maturation stages | Extended development, but incomplete maturation | Longest culture duration with advanced maturation |

For genetic studies and high-throughput drug screening, 2D monolayers remain the system of choice due to their scalability and reproducibility. The "village editing" approach exemplifies this utility, where CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing in a cell village format enabled efficient NRXN1 knockout across iPSC lines from 15 donors with varying polygenic risk scores for schizophrenia [4]. Such large-scale, genetically diverse studies would be prohibitively challenging in more complex 3D systems.

However, for modeling non-cell-autonomous disease mechanisms and circuit-level defects, assembloids provide unique capabilities. The extended culture durations possible with assembloids (up to 390 days in some reports) enable modeling of postnatal developmental events that were previously inaccessible in vitro [4]. This extended timeline is particularly valuable for neurodevelopmental disorders with postnatal onset or progression, allowing researchers to capture developmental processes that occur over extended periods in the human brain.

Signaling Pathways in Neural Development Models

The signaling pathways active in neural tissue models significantly influence their developmental trajectory and cellular composition. Comparative studies have revealed fundamental differences in how these pathways are engaged across different culture systems.

Diagram 1: Signaling Pathways in 2D vs 3D Neural Models

The diagram illustrates key signaling differences between 2D and 3D neural models. In 3D organoids, preserved cell-cell adhesion enables robust Notch signaling, maintaining radial glia in a progenitor state and supporting sequential generation of neuronal subtypes [25]. In contrast, 2D monolayers exhibit suppressed Notch signaling due to disrupted cell adhesion, leading to precocious differentiation and impaired generation of intermediate progenitors and outer radial glia [25]. Integrin signaling is enhanced in 2D systems, promoting increased proliferation but altering the normal developmental sequence of neurogenesis.

These signaling differences have profound implications for modeling neurodevelopmental disorders. For example, the village editing study of NRXN1 deletions in multiple genetic backgrounds found that genetic background deeply influences gene expression changes in NRXN1 knockout neurons, highlighting the importance of capturing gene-gene interactions in neurodevelopmental disorder models [4]. The more physiologically relevant signaling environment in 3D systems may provide a more accurate context for evaluating such genetic interactions and their contribution to disease risk.

Applications in Neurodevelopmental Disorder Research

Disease Modeling with Patient-Specific iPSCs