Molecular Mechanisms of Stem Cell Pluripotency and Self-Renewal: From Core Networks to Clinical Translation

This comprehensive review synthesizes current understanding of the intricate molecular mechanisms governing stem cell pluripotency and self-renewal.

Molecular Mechanisms of Stem Cell Pluripotency and Self-Renewal: From Core Networks to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This comprehensive review synthesizes current understanding of the intricate molecular mechanisms governing stem cell pluripotency and self-renewal. Covering foundational concepts through advanced applications, we examine the core transcriptional networks (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG), signaling pathways (LIF/STAT3, TGF-β/BMP, Wnt), and epigenetic regulators that maintain stem cell identity. The article explores methodological advances in induced pluripotency, disease modeling, and regenerative applications while addressing critical challenges including reprogramming efficiency, tumorigenic risk, and epigenetic instability. Through comparative analysis of embryonic, adult, and induced pluripotent stem cells, we provide researchers and drug development professionals with a strategic framework for optimizing stem cell technologies toward clinically viable therapies.

Core Molecular Networks: Decoding the Fundamental Mechanisms of Pluripotency

{# The OCT4-SOX2-NANOG Core Pluripotency Network}

Abstract: The transcriptional regulatory circuitry governed by the OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG trio constitutes the fundamental molecular framework for pluripotency and self-renewal in embryonic stem cells (ESCs). This in-depth technical guide synthesizes seminal and contemporary research to detail the architecture, functional mechanisms, and experimental interrogation of this core network. Framed within the broader context of stem cell pluripotency research, this whitepaper provides researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive resource, encompassing quantitative genomic data, detailed experimental methodologies, and essential research reagents.

The establishment and maintenance of the pluripotent state in embryonic stem cells (ESCs) are orchestrated by a core transcriptional network centered on three key transcription factors: OCT4 (a POU family homeodomain protein), SOX2 (an HMG-box protein), and NANOG (a homeodomain protein). These factors are essential for early mammalian development and the propagation of undifferentiated ESCs in culture [1] [2]. Their non-redundant functions were definitively established through genetic studies; for instance, disruption of OCT4 or NANOG leads to the aberrant differentiation of the inner cell mass (ICM) and ESCs into trophectoderm and extra-embryonic endoderm, respectively [1]. Furthermore, the groundbreaking discovery that somatic cell reprogramming to induced pluripotency is driven by these factors underscores their paramount importance in establishing cell identity [3].

This guide delves into the sophisticated regulatory circuitry formed by these factors, which integrates autoregulatory loops, feed-forward mechanisms, and epigenetic controls to sustain pluripotency while suppressing differentiation. We summarize key genomic findings, provide detailed experimental protocols for studying the network, and catalog essential research tools, providing a foundational resource for scientists exploring the mechanisms of stem cell biology and its therapeutic applications.

Core Network Architecture and Genomic Landscape

The core pluripotency network is characterized by extensive co-occupancy of genomic targets and interconnected regulatory loops. Genome-scale location analyses in human ESCs revealed that OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG co-occupy a substantial portion of their target genes, binding in close proximity to each other at promoter regions [1].

Quantitative Genomic Occupancy

The table below summarizes the promoter occupancy of OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG in human ESCs, as determined by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) coupled with DNA microarrays.

Table 1: Promoter Occupancy of Core Pluripotency Factors in Human ESCs

| Transcription Factor | Number of Occupied Protein-Coding Gene Promoters | Percentage of Annotated Promoters | Key Co-Occupancy Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|

| OCT4 | 623 | 3% (623/17,917) | ~50% of OCT4 sites are also bound by SOX2 [1] |

| SOX2 | 1,271 | 7% (1,271/17,917) | >90% of promoters bound by both OCT4 and SOX2 are also occupied by NANOG [1] |

| NANOG | 1,687 | 9% (1,687/17,917) | The three factors together co-occupy at least 353 genes [1] |

Functional Classes of Target Genes

A critical insight from location analysis is that the core factors frequently regulate genes encoding other transcription factors, particularly developmentally important homeodomain proteins [1]. This places OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG at the top of a hierarchical regulatory structure that governs ESC identity. Furthermore, they co-regulate miRNA genes, such as mir-137 and mir-301, adding a post-transcriptional layer to their regulatory control [1].

Autoregulatory and Feedforward Loops

The network exhibits a high degree of robustness through interconnected circuitry:

- Autoregulatory Loops: OCT4 and SOX2 regulate their own expression, ensuring their sustained levels in pluripotent cells [2].

- Feedforward Loops: OCT4 and SOX2 collaboratively regulate NANOG expression. NANOG, in turn, acts as a direct target and collaborator to reinforce the network [1] [2].

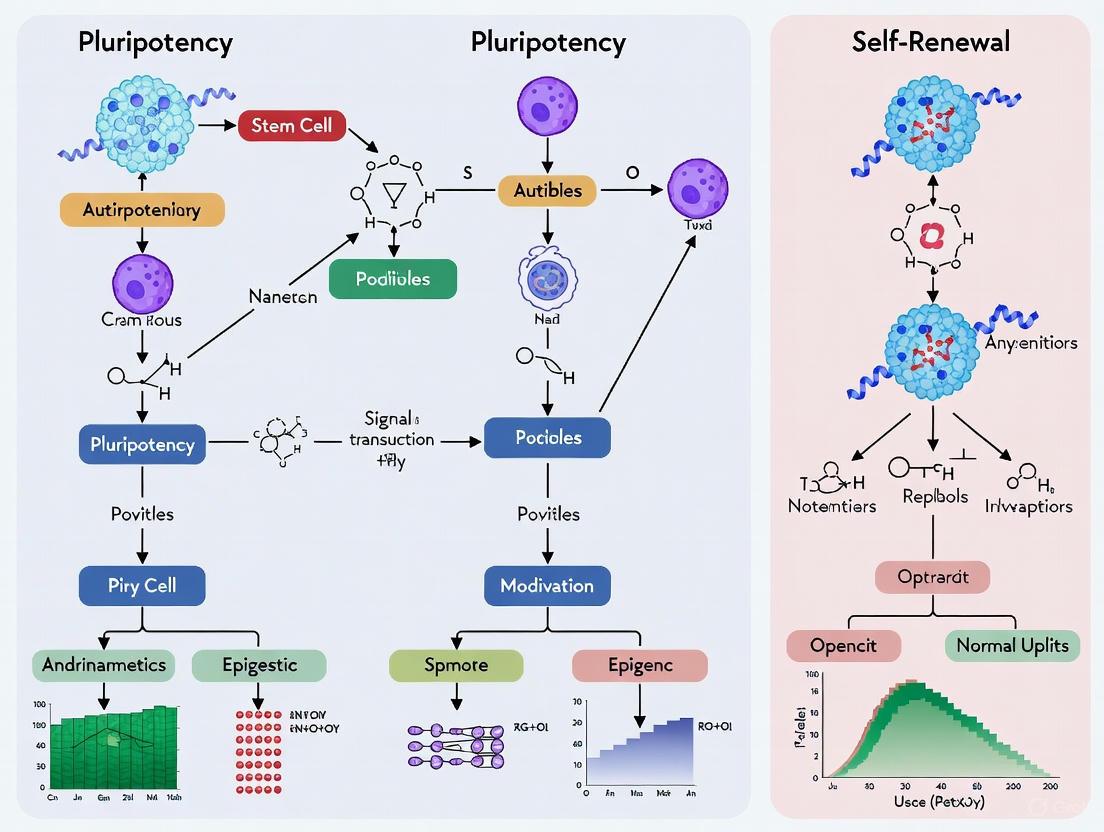

Diagram 1: The Core Pluripotency Network. This diagram illustrates the autoregulatory (red) and collaborative (blue/green) loops between OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG, and their joint regulation of downstream target genes to sustain pluripotency.

Experimental Methods for Investigating the Network

Genome-Scale Location Analysis (ChIP-on-Chip)

Objective: To identify the genome-wide binding sites of OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG in human ESCs [1].

Protocol:

- Cell Culture and Cross-linking: Grow H9 human ESCs (NIH code WA09) under standard, feeder-free conditions. Fix cells with formaldehyde to cross-link transcription factors to their DNA binding sites.

- Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP):

- Lyse cells and shear chromatin by sonication to generate random fragments of 200–1000 bp.

- Immunoprecipitate the cross-linked DNA-protein complexes using specific, validated antibodies against OCT4, SOX2, or NANOG. Include a control immunoprecipitation with a non-specific IgG.

- Microarray Hybridization (ChIP-on-Chip):

- Reverse cross-links and purify the enriched DNA.

- Hybridize the ChIP-enriched DNA and a sample of input (control) DNA to a custom-designed DNA microarray. The microarray contains ~60-mer oligonucleotide probes tiling the region from -8 kb to +2 kb relative to the transcription start sites of 17,917 annotated human genes.

- Data Analysis:

- Identify peaks of ChIP-enriched DNA that span closely neighboring probes.

- Compare the binding profiles of the three factors to determine co-occupied promoters. Binding sites for the cell-cycle transcription factor E2F4 can be used as a negative control to confirm the specificity of the stem cell regulator interactions.

Validation: The quality of the dataset is supported by the identification of previously known or suspected target genes (e.g., LEFTY2/EBAF, CRIPTO/TDGF1) and the use of improved protocols that, when tested in yeast, demonstrated a false positive rate of <1% and a false negative rate of ~20% [1].

CRISPR-DamID for Mapping Long-Range Chromatin Interactions

Objective: To identify extreme long-range chromatin interactions mediated by specific enhancers, such as the Oct4 distal enhancer (DE), in mouse ESCs [4].

Protocol:

- Construct Assembly: Fuse E. coli DNA adenine methyltransferase (Dam) to a catalytically dead Neisseria meningitidis Cas9 (dCas9). This fusion protein is placed under a doxycycline-inducible promoter in mouse ESCs.

- Targeting: Co-express guide RNAs (gRNAs) designed to target the Oct4 DE region. The dCas9-Dam fusion is recruited to this locus.

- Proximity Labeling: Upon induction with doxycycline, the Dam domain methylates adenines in GATC sequences found not only at the targeted site but also in nearby genomic regions engaged in long-range interactions, effectively labeling them.

- DNA Extraction and Processing:

- Harvest genomic DNA after 6 hours of induction.

- Digest the DNA with the methylation-sensitive restriction enzyme DpnI, which cuts only at methylated GATC sites. This is followed by digestion with DpnII, which cuts only at unmethylated GATC sites, to enrich for fragments from interacting loci.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Prepare sequencing libraries from the enriched fragments and sequence them.

- Data Analysis: Align sequenced reads to the reference genome and call significant peaks of interaction using tools like HOMER. Compare results with interaction profiles generated from 4C-seq and control cell lines (e.g., expressing NmCas9-Dam without gRNAs) to filter out background signals.

Application: This method identified the Oct4 DE interacting with genes on other chromosomes, including Lgl2 and Grb7, and validated their functional importance in maintaining pluripotency [4].

Diagram 2: CRISPR-DamID Workflow. This experimental flowchart outlines the key steps for identifying long-range chromatin interactions, from guide RNA design to bioinformatic analysis.

Advanced Regulatory Mechanisms

Distinct Roles in Establishment vs. Maintenance

Recent studies have refined our understanding of the functional roles of OCT4 and SOX2. By quantitatively analyzing the dynamic ranges of gene expression and employing targeted mutagenesis of OCT4:SOX2 motifs, research has shown that their binding is critically enriched near genes subject to large dynamic ranges of expression (e.g., >20-fold changes between ESCs and somatic cells) [3].

- Pioneering Activity: OCT4 and SOX2 possess pioneering activity, meaning they can engage nucleosomal DNA and promote chromatin remodeling, thereby establishing new transcriptional states during reprogramming [3].

- Establishment vs. Maintenance: Mutagenesis experiments revealed that OCT4:SOX2 composite motifs are essential for establishing both active and silent transcriptional states during the acquisition of pluripotency. However, they play a more limited role in the maintenance of these states in established pluripotent cells [3]. This suggests that once a transcriptional state is set, other factors may contribute to its stability.

Epigenetic Control and Interaction with Chromatin Modifiers

The core network operates in concert with epigenetic machinery to reinforce the pluripotent state.

- Promotion of an Active Chromatin State: In the presence of LIF, NANOG promotes chromatin accessibility and recruits other pluripotency factors like OCT4, SOX2, and ESRRB to thousands of enhancers. This rewiring of the network enhances self-renewal [5].

- Repression of Differentiation Genes: In the absence of LIF, NANOG helps block differentiation by sustaining the repressive histone mark H3K27me3 at key developmental regulators, such as Otx2 [5]. This links NANOG directly to the maintenance of bivalent chromatin domains.

- Spatial Genome Organization: Pluripotent cells exhibit a unique nuclear architecture. Genomic regions with high occupancy of OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG, as well as regions enriched with Polycomb proteins and H3K27me3, show a tendency to cluster together in the nucleus, creating distinct regulatory environments that are characteristic of the pluripotent state [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Studying the Core Pluripotency Network

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| H9 hESCs (WA09) | A well-characterized human embryonic stem cell line. | Served as the model system for the initial genome-scale location analysis of OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG [1]. |

| Specific Antibodies (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG) | For Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) and protein detection. | Essential for immunoprecipitating transcription factor-DNA complexes in ChIP assays to map genomic binding sites [1]. |

| Promoter & Enhancer Microarrays | Microarrays covering promoter regions of thousands of genes for ChIP-on-Chip. | Used to identify 623, 1271, and 1687 promoter targets of OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG, respectively [1]. |

| Inducible CRISPR-Activation System (e.g., SunTag) | For precise, inducible overexpression of endogenous genes. | Used to dissect the consequences of endogenous NANOG induction in mouse ESCs, revealing its context-dependent functions [5]. |

| dCas9-Dam Fusion Construct | For mapping long-range chromatin interactions via targeted proximity labeling (CRISPR-DamID). | Enabled the discovery of interchromosomal interactions between the Oct4 distal enhancer and the Lgl2 and Grb7 genes [4]. |

| E14 mESCs | A commonly used mouse embryonic stem cell line. | Used for studying long-range chromatin interactions and the functional roles of Oct4:Sox2 binding in a native context [3] [4]. |

The OCT4-SOX2-NANOG core represents a paradigm of a robust, self-sustaining transcriptional network that is fundamental to pluripotency. The experimental data demonstrate that these factors do not operate in isolation but function collaboratively through extensive co-occupancy of genomic targets and intricate autoregulatory circuits. Contemporary research continues to uncover layers of complexity, revealing their distinct temporal roles in establishing versus maintaining transcriptional states [3], their intricate crosstalk with signaling pathways like LIF and BMP [5] [7], and their influence on the 3D architecture of the genome [4] [6].

Future investigations will likely focus on quantitatively modeling the dynamics of this network, understanding its heterogeneity in stem cell populations, and exploiting this knowledge to improve the efficiency and fidelity of cellular reprogramming for regenerative medicine. A deep understanding of this core circuitry is not only essential for basic stem cell biology but also for comprehending how its dysregulation may contribute to diseases such as cancer.

The maintenance of pluripotency and self-renewal in embryonic stem cells (ESCs) is not governed by a single pathway but is instead the result of a complex, integrated signaling network. The core of this network involves the precise interplay between the LIF/STAT3, TGF-β/Activin/Nodal, and BMP pathways, which communicate extensively to coordinate cell fate decisions [8] [9]. These interactions are highly dependent on the species-specific pluripotency state—"naïve" in mouse ESCs (mESCs) and "primed" in human ESCs (hESCs)—and determine whether a cell remains undifferentiated or commits to a particular lineage [8] [10]. Dysregulation of this cross-talk is implicated in developmental defects and disease, underscoring its biological importance [11] [12]. This review provides an in-depth analysis of the molecular mechanisms underlying this signaling integration, framed within the context of stem cell pluripotency research for a scientific audience.

Core Pathway Architectures and Functions

LIF/STAT3 Signaling

The LIF/STAT3 pathway is a cornerstone for maintaining the naïve pluripotent state in mESCs [9] [10]. The binding of Leukemia Inhibitory Factor (LIF) to its heterodimeric receptor (LIFR and GP130) initiates intracellular signaling, which is transduced primarily through the JAK/STAT module.

- Mechanism: Receptor activation triggers the phosphorylation of Janus Kinases (JAKs), which in turn phosphorylate Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 (STAT3) on tyrosine residues [13]. Phosphorylated STAT3 (p-STAT3) dimerizes and translocates to the nucleus, where it binds to specific genomic sites and activates the transcription of key pluripotency genes, including Tbx3, Gjb3, Ly6g6e, and Esrrb [13] [9].

- Functional Role: In mESCs, LIF/STAT3 activation is sufficient to suppress differentiation and sustain self-renewal, even in the absence of feeder cells [9] [10]. Its activity is tightly linked to the core pluripotency transcription factor network; for instance, STAT3 physically interacts with the genomic loci occupied by Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog [9]. In primed hESCs, however, the role of LIF/STAT3 is less pronounced, highlighting a key species-specific difference.

TGF-β/Activin/Nodal Signaling

The TGF-β/Activin/Nodal branch signals through a canonical SMAD2/3 cascade and is crucial for maintaining the primed pluripotent state characteristic of hESCs [8] [14].

- Mechanism: Ligands (TGF-β, Activin A, Nodal) bind to type I and type II receptor complexes (e.g., ALK5/TGFBR1 and TGFBR2), leading to the phosphorylation and activation of the Receptor-SMADs, SMAD2 and SMAD3 [11] [12]. Activated R-SMADS form a complex with the common mediator SMAD4, and this complex accumulates in the nucleus to regulate target gene expression.

- Functional Role: In hESCs, this pathway is instrumental for self-renewal. It directly activates the expression of Nanog and collaborates with other factors to sustain the expression of Oct4 and Sox2 [8]. It maintains pluripotency partly by suppressing autocrine BMP signaling, which would otherwise promote differentiation [8]. The pathway's effect is concentration-dependent; for example, low Activin A (5 ng/mL) supports pluripotency, while high concentrations (50–100 ng/mL) drive endodermal differentiation [8].

BMP Signaling

The BMP pathway exerts context-dependent effects on pluripotency, with distinct, and often opposing, functions compared to the TGF-β/Activin/Nodal branch [8] [15] [16].

- Mechanism: BMP ligands (e.g., BMP4) bind to receptor complexes involving type I receptors (ALK1, ALK2, ALK3, ALK6) and type II receptors (BMPR2, ActRIIA, ActRIIB). This triggers the phosphorylation of SMAD1, SMAD5, and SMAD8 [11] [12]. These R-SMADS then partner with SMAD4, and the complex translocates to the nucleus to regulate transcription.

- Functional Role: In mESCs, BMP4 works synergistically with LIF to support self-renewal. It does so by inducing the expression of Id genes, which inhibit neural differentiation, and by suppressing the ERK/MAPK pathway, a pro-differentiation signal [8]. In stark contrast, in hESCs, BMP4 promotes differentiation towards trophectoderm and other extra-embryonic lineages [14] [16]. This dichotomy is a primary example of the antagonism observed between the BMP and TGF-β/Activin/Nodal pathways in primed pluripotency [15].

Table 1: Core Signaling Pathways in Pluripotency

| Pathway | Key Ligands | Receptors | Signal Transducers | Primary Role in Naïve mESCs | Primary Role in Primed hESCs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LIF/STAT3 | LIF | LIFR/GP130 | JAK, STAT3 | Promotes self-renewal; Core pluripotency support [9] [10] | Limited role; Not a primary pluripotency driver [10] |

| TGF-β/Activin/Nodal | TGF-β, Activin A, Nodal | ALK4/5/7, TGFBR2 | SMAD2/3, SMAD4 | Limited role in self-renewal [8] | Promotes self-renewal; Activates Nanog; Suppresses BMP [8] [14] |

| BMP | BMP4 | ALK1/2/3/6, BMPR2/ActRII | SMAD1/5/8, SMAD4 | Promotes self-renewal with LIF; Induces Id genes [8] | Promotes differentiation; Drives trophectoderm fate [14] [16] |

Molecular Mechanisms of Pathway Crosstalk

The integration of these pathways occurs at multiple molecular levels, creating a finely tuned regulatory network.

SMAD Protein Integration and Competition

The shared use of SMAD4 by both the TGF-β/Activin/Nodal and BMP pathways creates a central hub for cross-talk. The limited cellular pool of SMAD4 means that active R-SMAD complexes must compete for this common partner to form transcriptionally active complexes [16]. This competition can lead to antagonism; for instance, during palatal shelf development, TGF-β signaling sequesters SMAD4 into complexes with p-SMAD2/3, thereby limiting its availability for BMP-activated p-SMAD1/5/8 and inhibiting the BMP transcriptional response [16]. This mechanism illustrates how one pathway can directly modulate the output of another.

Transcriptional Regulation of Pluripotency Factors

The downstream effectors of these pathways converge directly on the core pluripotency transcriptional network. For example:

- SMAD2/3, activated by TGF-β/Activin, binds to the Nanog promoter and is essential for its expression in hESCs [8].

- STAT3, activated by LIF, cooperates with transcription factors like Klf4 to sustain the expression of Oct4 and other pluripotency factors in mESCs [9] [10].

- BMP-SMAD signaling in mESCs induces Id proteins, which indirectly support the pluripotency network by inhibiting differentiation-promoting transcription factors [8].

Cytoplasmic Kinase Networks: MAPK/ERK

The MAPK/ERK pathway serves as a critical node for non-canonical signaling and cross-talk. While FGF/ERK signaling typically promotes differentiation in mESCs, its activity is modulated by other pathways [10]. BMP signaling in mESCs has been shown to help maintain self-renewal by suppressing the pro-differentiation ERK/MAPK pathway [8]. Furthermore, ERK can directly phosphorylate the linker region of SMAD proteins, which can inhibit their activity and nuclear translocation, as seen with BMP-activated SMAD1/5 [11]. This represents a key mechanism by which growth factor signaling (e.g., via FGF receptors) can fine-tune or antagonize TGF-β/BMP canonical signaling.

Diagram 1: Integrated Signaling Network in Pluripotency. The diagram illustrates the core LIF/STAT3, TGF-β/Activin/Nodal, and BMP pathways, highlighting points of convergence and antagonism, such as the competition for SMAD4 and the inhibitory effect of ERK on BMP-SMADs.

Functional Outcomes in Pluripotency and Differentiation

The integrated output of these signaling pathways dictates cell fate.

- Naïve Pluripotency in mESCs: This state is maintained by the synergistic action of LIF/STAT3 and BMP4. LIF/STAT3 activates a core pluripotency program, while BMP4 simultaneously blocks alternative differentiation pathways, such as neural fate, via Id proteins [8] [9].

- Primed Pluripotency in hESCs: This state relies on a balance between TGF-β/Activin and BMP signaling, which act antagonistically. TGF-β/Activin signaling promotes self-renewal and directly activates Nanog, while BMP signaling drives differentiation. The dominance of TGF-β/Activin signaling in standard hESC culture conditions maintains the undifferentiated state [8] [14].

- Lineage Specification: The cross-talk between these pathways is also critical for the initial steps of differentiation. For example, the interplay between BMP, TGF-β, and Notch signaling is essential for inducing epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) during heart valve formation [16]. Similarly, in mESCs, BMP signaling can induce mesodermal fate in the absence of LIF [8].

Table 2: Experimental Evidence of Pathway Crosstalk

| Experimental Context | Key Finding | Molecular Mechanism | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Palatal shelf development (mouse) | TGF-β signaling inhibits BMP signaling outcomes. | Preferential sequestration of limited SMAD4 by p-SMAD2/3, outcompeting p-SMAD1/5/8 [16]. | [16] |

| hESC self-renewal | Activin/Nodal signaling maintains pluripotency. | SMAD2/3 binds to and activates the Nanog promoter, while simultaneously suppressing autocrine BMP signaling [8]. | [8] |

| mESC self-renewal | BMP4 works with LIF to sustain pluripotency. | BMP-SMAD signaling induces Id genes, which inhibit neural differentiation, and suppresses the ERK/MAPK pathway [8]. | [8] |

| Oncogenic Ras models | Ras/ERK activation inhibits TGF-β cytostatic responses. | ERK phosphorylates the linker region of SMAD2/3, inhibiting their transcriptional activity without affecting nuclear translocation [11]. | [11] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Advancing research in this field requires a specific toolkit of reagents to manipulate and monitor these signaling pathways.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Pathway Analysis

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Target | Example Use in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant LIF | Activates LIF/STAT3 pathway | Maintain naive pluripotency in mESC cultures [9] [10]. |

| Recombinant Activin A | Activates TGF-β/SMAD2/3 pathway | Maintain primed pluripotency in hESCs at low concentrations (e.g., 5 ng/mL); induce endoderm at high concentrations [8]. |

| Recombinant BMP4 | Activates BMP/SMAD1/5/8 pathway | Support mESC self-renewal in combination with LIF; induce differentiation in hESCs [8] [16]. |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors (e.g., SB431542) | Inhibits TGF-β/Activin type I receptors (ALK4/5/7) | Functionally disrupt TGF-β/Activin/Nodal signaling to study its role in pluripotency and differentiation [8]. |

| STAT3 Inhibitors (e.g., Stattic) | Inhibits STAT3 activation and dimerization | Probe the necessity of the LIF/STAT3 pathway in naive state maintenance [9]. |

| Phospho-Specific Antibodies (p-STAT3, p-SMAD1/5/8, p-SMAD2/3) | Detect activated pathway components | Monitor pathway activity and cross-talk through Western blot, immunofluorescence, and flow cytometry [13]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Analyzing Pathway Crosstalk in ESCs

The following protocol provides a methodology for investigating the functional cross-talk between the LIF/STAT3 and BMP pathways in murine ESCs, adaptable for other pathway interactions.

Objectives and Workflow

Primary Objective: To determine how BMP signaling modulation influences LIF/STAT3 transcriptional activity and its role in maintaining the naive pluripotent state.

Experimental Workflow:

- Cell Culture and Treatment: Culture mouse ESCs (e.g., E14TG2a) in a defined medium like N2B27 supplemented with LIF. Split cells and seed them for experimentation. Once stabilized, treat the cells for 24-48 hours under the following conditions:

- Condition A (Control): LIF-containing medium.

- Condition B (BMP Inhibition): LIF-containing medium + a BMP receptor inhibitor (e.g., LDN-193189, 100 nM).

- Condition C (BMP Activation): LIF-containing medium + recombinant BMP4 (e.g., 10-50 ng/mL).

- Sample Collection: Harvest cells from each condition for downstream molecular analyses. Collect samples for RNA extraction (qRT-PCR), protein extraction (Western Blot), and fixation (Immunofluorescence).

- Functional Readouts:

- Molecular Analysis: Perform qRT-PCR to quantify mRNA levels of LIF/STAT3 target genes (Tbx3, Esrrb), a BMP target gene (Id1), and core pluripotency factors (Nanog, Oct4). Perform Western Blot to analyze protein levels and phosphorylation status of STAT3, SMAD1/5, and ERK.

- Phenotypic Analysis: Assess colony morphology and the expression of pluripotency markers (e.g., Oct4, Nanog) via immunofluorescence. Quantify the alkaline phosphatase activity, a marker for undifferentiated mESCs.

Expected Outcomes and Interpretation

- Condition B (BMP Inhibition): Expected reduction in Id1 expression (confirming BMP inhibition). A subsequent reduction in Tbx3 and Nanog would suggest that BMP signaling is required for the full transcriptional output of the LIF/STAT3 pathway and optimal pluripotency network stability.

- Condition C (BMP Activation): Expected increase in Id1. If LIF/STAT3 target genes and pluripotency markers are maintained or enhanced, it confirms synergistic support of the naive state. If differentiation markers (e.g., FGF5) appear, it may indicate a disruption of the naive balance.

This protocol allows for a direct assessment of how one pathway (BMP) modulates the activity of another (LIF/STAT3) to control the pluripotent state.

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Analyzing LIF/STAT3 and BMP Crosstalk. The diagram outlines the key steps in a protocol designed to probe the functional interaction between two major pluripotency pathways, from cell culture and treatment to molecular and phenotypic analysis.

The precise integration of the LIF/STAT3, TGF-β/Activin/Nodal, and BMP signaling pathways forms the bedrock of the regulatory circuitry governing stem cell pluripotency and fate decisions. Their cross-talk, mediated through mechanisms like SMAD competition, transcriptional synergy, and cytoplasmic kinase networks, creates a robust and flexible system that responds to extracellular cues. A deep and mechanistic understanding of this network is not only fundamental to developmental biology but also critical for advancing applications in regenerative medicine, disease modeling, and drug discovery. Future research using precise genetic and chemical tools will continue to unravel the complexities of this signaling integration, ultimately enhancing our ability to control cell fate for therapeutic purposes.

Epigenetic regulation serves as the fundamental mechanism governing stem cell pluripotency and self-renewal, orchestrating gene expression patterns without altering the underlying DNA sequence. This technical review examines the sophisticated interplay between histone modifications and DNA methylation in directing stem cell fate decisions. Within the context of developmental biology and regenerative medicine, we analyze how these epigenetic marks function as molecular switches that maintain the delicate balance between self-renewal and differentiation. The dynamic nature of these modifications enables stem cells to retain multilineage potential while remaining responsive to developmental cues. Drawing from recent advancements in single-cell multi-omics and epigenetic editing technologies, this whitepaper provides a comprehensive framework for understanding how epigenetic mechanisms control cellular identity, with significant implications for therapeutic development in regenerative medicine and cancer treatment.

Stem cell functionality hinges upon the precise regulation of two defining characteristics: pluripotency, the capacity to differentiate into diverse cell types, and self-renewal, the ability to perpetuate the stem cell pool throughout life [17]. The molecular programs governing these properties extend beyond transcription factor networks to encompass sophisticated epigenetic controls that determine chromatin accessibility and transcriptional potential [18] [19]. DNA methylation and histone modifications constitute complementary regulatory layers that establish and maintain cellular identity during development [20] [21].

The transition from totipotent zygote to pluripotent stem cell and subsequent lineage commitment involves extensive epigenetic reprogramming, including genome-wide demethylation followed by re-establishment of methylation patterns in a cell-type-specific manner [21]. Similarly, histone modifications create a landscape of permissive and repressive chromatin domains that guide differentiation trajectories [22]. These epigenetic mechanisms collectively form a molecular infrastructure that stabilizes developmental transitions while retaining a degree of plasticity necessary for normal development and tissue homeostasis [23] [19].

Histone Modifications: Dynamic Regulators of Chromatin State

Key Histone Modifications and Their Functional Roles

Histone modifications serve as versatile epigenetic marks that directly influence chromatin architecture and gene expression patterns in stem cells [22]. These post-translational modifications occur predominantly on histone N-terminal tails and include methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination. The functional consequences of these modifications depend on specific residues modified, degree of modification (mono-, di-, or tri-methylation), and combinatorial effects with other epigenetic marks [19].

Table 1: Major Histone Modifications in Stem Cell Pluripotency and Differentiation

| Modification | Chromatin State | Functional Role in Stem Cells | Writer Complexes | Eraser Enzymes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3K4me3 | Active | Marks promoters of active pluripotency genes (OCT4, SOX2) [19] | SET1/COMPASS, MLL complexes [22] | KDM5 family |

| H3K27me3 | Repressive | Silences developmental genes in pluripotent state; PRC2-mediated [22] [19] | PRC2 (EZH1/2) [22] | KDM6 family (UTX) [19] |

| H3K9me3 | Repressive | Associated with heterochromatin; repressed in pluripotent cells [19] | SUV39H1 [19] | KDM4 family [19] |

| H3K27ac | Active | Marks active enhancers; increased during differentiation [19] | p300/CBP | HDAC1-3 |

| H3K9ac | Active | Associated with open chromatin; promotes transcription [19] | GCN5/PCAF | HDAC1-3 |

| Bivalent Domains (H3K4me3 + H3K27me3) | Poised | Marks developmental genes in ESCs; "poised" for activation upon differentiation [22] | SET1/COMPASS + PRC2 | Dual demethylase activity |

The bivalent domain configuration, characterized by the simultaneous presence of H3K4me3 (activating) and H3K27me3 (repressing) marks at promoter regions of key developmental regulators, represents a particularly important chromatin state in pluripotent stem cells [22]. This configuration maintains genes in a transcriptionally poised state, enabling rapid activation or permanent silencing in response to differentiation signals [22] [19]. During lineage commitment, bivalent domains resolve to monovalent states through the loss of one modification, thereby establishing stable expression patterns appropriate for specific cell fates [19].

Metabolic and Cell Cycle Regulation of Histone Modifications

The establishment and maintenance of histone modifications are influenced by global cellular processes, including metabolism and cell cycle progression. Stem cells exhibit a specialized metabolism that directly impacts the epigenetic landscape by regulating substrate availability for histone-modifying enzymes [22]. Key metabolites including acetyl-CoA, S-adenosyl methionine (SAM), NAD, and α-ketoglutarate serve as essential cofactors for histone-modifying enzymes, creating a direct link between cellular metabolic state and epigenetic regulation [22].

The cell cycle imposes another layer of regulation on the histone modification landscape. With each replication cycle, newly synthesized histones are incorporated into chromatin, diluting existing modification patterns [22]. The re-establishment of histone marks on nascent chromatin occurs with different kinetics—some modifications like H3K27me1/2 and H3K36me1 are imposed quickly after deposition, while heterochromatic marks such as H3K9me3 accumulate more slowly over multiple cell cycles [22]. This dynamic creates a relationship between cell cycle length and epigenetic plasticity, with rapidly dividing stem cells maintaining more acetylated chromatin states while slower-cycling cells accumulate repressive methylation marks [22].

Diagram 1: Interplay between histone modifications, metabolism, and cell cycle in regulating stem cell identity. Metabolic states provide essential cofactors for histone-modifying enzymes, which establish chromatin states that determine gene expression profiles and cellular identity. The cell cycle periodically dilutes histone marks through replication, creating dynamic regulation.

DNA Methylation: Stable Repressive Control in Fate Determination

Molecular Machinery and Dynamics During Development

DNA methylation involves the covalent addition of a methyl group to the 5-carbon position of cytosine bases within CpG dinucleotides, primarily catalyzed by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) [20]. This epigenetic modification typically associates with transcriptional repression when present in promoter regions, though it can also facilitate transcription when located in gene bodies [20]. The mammalian DNA methylation system comprises multiple enzymes with specialized functions: DNMT1 maintains methylation patterns during DNA replication, while DNMT3A, DNMT3B, and DNMT3C perform de novo methylation [20]. DNMT3L, though catalytically inactive, serves as a crucial cofactor that enhances de novo methylation activity [20].

The dynamics of DNA methylation during mammalian development involve dramatic waves of genome-wide demethylation followed by lineage-specific remethylation [20] [21]. Primordial germ cells (PGCs) undergo extensive DNA demethylation, erasing parental epigenetic marks to restore totipotency [21]. Similarly, the early embryo experiences global demethylation post-fertilization, with the paternal genome undergoing active demethylation before the first cleavage division and the maternal genome undergoing passive demethylation in subsequent divisions [21]. These reprogramming events create a hypomethylated state that characterizes pluripotent cells, with DNA methylation levels progressively increasing during differentiation to stabilize lineage commitment [21] [24].

Table 2: DNA Methylation Machinery and Developmental Functions

| Enzyme/Protein | Type | Function | Phenotype of Loss-of-Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNMT1 | Maintenance methyltransferase | Copies methylation patterns during DNA replication | Apoptosis of germline stem cells; hypogonadism and meiotic arrest [20] |

| DNMT3A | De novo methyltransferase | Establishes new methylation patterns during development | Abnormal spermatogonial function [20] |

| DNMT3B | De novo methyltransferase | Establishes new methylation patterns during development | Fertility with no distinctive phenotype [20] |

| DNMT3C | De novo methyltransferase | Testis-specific de novo methylation | Severe defect in DSB repair and homologous chromosome synapsis during meiosis [20] |

| DNMT3L | Cofactor | Enhances DNMT3A/B activity; targets retrotransposons | Decrease in quiescence SSCs [20] |

| TET1/2/3 | Demethylase | Initiates active DNA demethylation via 5mC oxidation | Fertile (TET1/2); role in reprogramming [20] |

DNA Methylation in Lineage Restriction and Germline Specification

DNA methylation plays a critical role in restricting developmental potential during stem cell differentiation. Studies using DNA methylation-free embryonic stem cells (ESCs) with triple DNMT knockout (TKO) demonstrate that the absence of DNA methylation skews differentiation potential, enhancing neural lineage specification while extending competence for primordial germ cell-like cell (PGCLC) formation [24]. This suggests that DNA methylation serves as a barrier that regulates the temporal window for specific lineage commitments during early development.

The mechanism by which DNA methylation controls lineage preference involves its influence on enhancer dynamics. In the absence of DNA methylation, enhancers associated with both neural and germline lineages fail to be properly decommissioned during exit from the naive pluripotent state, maintaining a permissive chromatin environment for these related lineages [24]. This results in a coordinated neural-germline axis that remains accessible in DNA methylation-deficient cells, revealing how DNA methylation normally constrains this developmental trajectory to appropriate developmental timing.

During germ cell development, DNA methylation dynamics are particularly crucial. Mouse primordial germ cells undergo genome-wide DNA demethylation between embryonic days 8.5-13.5, reducing 5mC levels to approximately 16.3% compared to 75% in embryonic stem cells [20]. This hypomethylation is driven by repression of de novo methyltransferases DNMT3A/B and elevated activity of DNA demethylation factors like TET1 [20]. The subsequent re-establishment of DNA methylation patterns during spermatogonial development demonstrates the precise regulation of this epigenetic mark in germline stem cell function [20].

Experimental Approaches: Methodologies for Epigenetic Analysis

Advanced Microscopy Techniques for Epigenetic Visualization

Microscopy-based approaches provide spatial and quantitative information about epigenetic marks that complement sequencing-based methods [25]. These techniques enable direct visualization of epigenetic modifications within single cells, preserving architectural context that is lost in bulk analyses.

Super-resolution microscopy (SRM), particularly single-molecule localization microscopy (SMLM), has been employed to map histone modifications on meiotic chromosomes with nanometer-scale precision [25]. This approach revealed distinct spatial patterns for different histone modifications: H3K4me3 extends outward in loop structures from the synaptonemal complex, H3K27me3 forms periodic clusters along the chromosome axis, and H3K9me3 localizes to centromeric regions [25]. Such detailed spatial information helps elucidate the functional significance of these modifications in chromosomal events.

Electron microscopy (EM) with immunogold labeling enables ultrastructural localization of DNA methylation marks like 5-methylcytosine (5mC) [25]. Surprisingly, EM studies have revealed that 5mC shows decreasing density toward the nuclear envelope, contrary to expectations given its association with heterochromatin [25]. This paradox may reflect limited antibody accessibility in highly condensed chromatin regions, highlighting both the utility and potential limitations of microscopy-based epigenetic mapping.

FLIM-FRET (Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging-Förster Resonance Energy Transfer) microscopy provides a powerful approach for studying chromatin compaction states [25]. Since FRET efficiency is distance-dependent, it can probe the proximity of fluorophores tagged to chromatin components, with higher FRET efficiency indicating more condensed heterochromatin [25]. This technique has been applied to measure DNA compaction, gene activity, and chromatin changes in response to various stimuli [25].

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for visualizing epigenetic modifications. The process begins with sample preparation, followed by specific labeling of epigenetic marks, advanced microscopy imaging, computational analysis, and biological interpretation. Microscopy approaches complement sequencing methods through data integration.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Epigenetic Studies in Stem Cells

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Histone Modification Antibodies | Anti-H3K4me3, Anti-H3K27me3, Anti-H3K9ac | Detection and localization of specific histone marks | ChIP-seq, Immunofluorescence, Western blot [22] [25] |

| DNA Methylation Detection Tools | Anti-5mC, Methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes | Identify methylated DNA regions | Immunofluorescence, BS-seq, MeDIP-seq [20] [25] |

| Epigenetic Enzyme Inhibitors | Valproic acid (HDACi), EZH2 inhibitors, DNMT inhibitors (5-aza) | Manipulate epigenetic marks to study function | Reprogramming studies, Cancer stem cell targeting [19] |

| Metabolic Regulators | Methionine, Threonine, SAM precursors | Modulate substrate availability for epigenetic enzymes | Study metabolism-epigenetics interplay [22] |

| Reprogramming Factors | OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC | Induce pluripotency in somatic cells | iPSC generation studies [18] [19] |

| Epigenetic Reporters | MBD-based sensors, HMRD-based sensors | Live imaging of epigenetic marks | Real-time tracking of epigenetic dynamics [25] |

Discussion: Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

The intricate interplay between histone modifications and DNA methylation creates a robust yet plastic regulatory network that maintains stem cell identity while allowing responsive differentiation. The therapeutic implications of understanding these mechanisms are substantial, particularly in regenerative medicine and oncology. Cancer stem cells (CSCs) utilize similar epigenetic mechanisms to maintain their self-renewing capacity and resistance to therapies [19]. For instance, EZH2-mediated H3K27me3 is frequently overexpressed in CSCs, silencing tumor suppressor genes and maintaining an undifferentiated state [19]. Similarly, DNA methylation patterns in cancerous cells often mirror those observed in stem cells, highlighting the reactivation of developmental programs in tumorigenesis [19].

Emerging therapeutic strategies aim to target these epigenetic mechanisms. HDAC inhibitors like valproic acid have been shown to enhance reprogramming efficiency in induced pluripotent stem cell generation [19]. EZH2 inhibitors are being explored to disrupt CSC maintenance in various cancers [19]. DNMT inhibitors such as 5-azacytidine have demonstrated potential in reversing aberrant methylation patterns in cancer cells [20] [19]. However, challenges remain in achieving selectivity and avoiding broad epigenetic disruptions that might activate oncogenes or impair normal stem cell function.

Future research directions should focus on developing more precise epigenetic editing tools, such as CRISPR-based systems that can target specific loci for modification rather than global epigenetic manipulation. Single-cell multi-omics approaches will provide deeper insights into the heterogeneity of epigenetic states within stem cell populations [20]. Additionally, understanding the metabolic regulation of epigenetic modifications may reveal new therapeutic avenues for manipulating stem cell fate in controlled manner [22]. As our knowledge of epigenetic regulation in stem cells advances, so too will our ability to harness these mechanisms for therapeutic intervention in degenerative diseases, aging, and cancer.

{start of main content}

Metabolic Control: Glycolytic Shift and Mitochondrial Reprogramming in Pluripotency

An In-Depth Technical Guide for Stem Cell Research and Therapeutic Development

The acquisition and maintenance of pluripotency in stem cells are metabolically active processes, not mere passive consequences of a transcriptional program. A fundamental metabolic reprogramming event—a switch from oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) to aerobic glycolysis—is now recognized as a critical driver for inducing and sustaining the pluripotent state [26] [27] [28]. This shift, reminiscent of the Warburg effect in cancer cells, supports the anabolic demands of rapid proliferation and provides essential biosynthetic precursors while simultaneously influencing the epigenetic landscape [26] [29]. Concurrently, mitochondria undergo a profound functional and structural transformation, relinquishing their primary role as energy powerhouses to become signaling hubs that orchestrate pluripotency [26] [30]. Understanding the precise mechanisms governing this metabolic control is paramount for improving the efficiency and safety of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) generation, enhancing directed differentiation protocols for disease modeling and drug screening, and advancing the translational potential of regenerative medicine. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical analysis of the glycolytic shift and mitochondrial reprogramming, framing them within the core mechanisms of stem cell pluripotency and self-renewal research.

The Metabolic and Mitochondrial Phenotype of Pluripotency

The Glycolytic State

Pluripotent stem cells (PSCs), including both embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), exhibit a characteristic reliance on glycolysis for energy production, even in the presence of ample oxygen [26] [27]. This metabolic configuration is not an indicator of mitochondrial dysfunction but an active adaptation to meet the unique demands of a pluripotent cell. Key features of this state include:

- High Glycolytic Flux: PSCs demonstrate elevated glucose consumption and lactate secretion, indicative of a high flux through the glycolytic pathway [27]. This rapid ATP generation, though inefficient per glucose molecule, supports fast cell multiplication [26].

- Biosynthetic Precursor Supply: Glycolytic intermediates are shunted into ancillary pathways, such as the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), to generate nucleotides, amino acids, and lipids essential for building the biomass required for continuous self-renewal [26] [29].

- Transcriptional and Enzyme Regulation: The core pluripotency factors OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG directly upregulate key glycolytic enzymes, including hexokinase 2 (HK2) and the M2 isoform of pyruvate kinase (PKM2) [27]. This creates a positive feedback loop where pluripotency factors reinforce the metabolic state that supports their expression.

Mitochondrial Reconfiguration

The metabolic shift to glycolysis is accompanied by a dramatic restructuring of the mitochondrial network, reflecting a state of functional immaturity that is primed for later differentiation.

Table 1: Mitochondrial Characteristics in Somatic Cells vs. Pluripotent Stem Cells

| Characteristic | Differentiated Somatic Cells | Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs/ESCs) |

|---|---|---|

| Morphology | Elongated, tubular, branched network [26] | Round, globular, punctate organelles [26] [27] |

| Cristae Structure | Highly developed, cristae-rich [26] | Poorly developed, immature cristae [26] [27] |

| Subcellular Distribution | Reticulated throughout the cytoplasm | Perinuclear localization [26] [27] |

| mtDNA Copy Number | High [26] | Low [26] [27] |

| Primary Metabolic Function | Oxidative Phosphorylation (OXPHOS) [26] | Glycolysis, signaling [26] |

| Membrane Potential (ΔΨ) | High, coupled to ATP production | Variable; reported as both low and hyperpolarized [26] |

This mitochondrial "reversion" is an active process facilitated by mechanisms such as NIX-mediated mitophagy, which clears the somatic mitochondrial population during the early stages of reprogramming [26]. Despite their immature structure, mitochondria in PSCs are not inert; they maintain a functional electron transport chain (ETC) and are capable of producing ATP via OXPHOS, though this contributes less to the total energy budget [26] [27]. Their role extends beyond energy production to include the generation of metabolites like α-ketoglutarate (αKG), which serve as cofactors for epigenetic enzymes, thereby linking mitochondrial metabolism to the regulation of the pluripotent epigenome [29].

Molecular Mechanisms Governing the Metabolic Shift

The transition from a somatic to a pluripotent metabolic state is orchestrated by a complex interplay of transcription factors, signaling pathways, and mitochondrial dynamics.

Core Pluripotency Factors as Metabolic Regulators

The Yamanaka factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC) directly instigate metabolic reprogramming. c-MYC is a well-known master regulator of glycolytic genes in cancer and similarly upregulates glycolysis in PSCs [27]. OCT4 and SOX2 contribute by binding to the promoter regions of glycolytic genes like Hk2 and Pkm2, enhancing their expression and cementing the glycolytic flux [27]. Furthermore, the non-coding RNA Lncenc1 interacts with proteins PTBP1 and HNRNPK to form a complex that occupies promoter regions of glycolytic genes, further promoting their transcription and sustaining the self-renewal capacity of ESCs [27].

Signaling Pathways and Environmental Cues

- Hypoxia-Inducible Factors (HIFs): A hypoxic microenvironment, typical of the inner cell mass, stabilizes HIFα subunits. HIF2α promotes the expression of core pluripotency factors, while HIF1α activates the transcription of glycolytic enzymes and represses mitochondrial OXPHOS, thereby reinforcing the glycolytic phenotype [27] [30].

- PKCλ/ι-HIF1α-PGC1α Axis: The atypical protein kinase C lambda/iota (PKCλ/ι) has been identified as a key upstream regulator. Depletion of PKCλ/ι in ESCs leads to impaired mitochondrial maturation and a sustained glycolytic state, even under differentiating conditions. Mechanistically, PKCλ/ι regulates the transcription of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC1α), a master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis, through a mechanism involving HIF1α [30]. This pathway represents a crucial node balancing self-renewal and the capacity for differentiation.

- Sirtuin Signaling: The NAD+-dependent deacetylase SIRT1, whose activity is governed by the cytoplasmic NAD+/NADH ratio (a reflection of glycolytic flux), has been implicated in metabolic fate decisions. In muscle progenitor cells, SIRT1 activity directly interacts with the transcriptional co-repressor p107, impeding its mitochondrial localization and thereby influencing OXPHOS and cell cycle progression [31]. This highlights a conserved mechanism where metabolic status feeds back to regulate proliferation.

Mitochondrial Dynamics and Quality Control

The balance between mitochondrial fission and fusion is critical for reprogramming. Reprogramming-induced mitochondrial fission, governed by the profission dynamin-related protein 1 (DRP1), is necessary for the full activation of pluripotency [28] [29]. This fragmentation facilitates the removal of older, somatic mitochondria via selective autophagy (mitophagy) and is associated with the metabolic shift towards glycolysis. Proteins such as PINK1 and PARKIN are known to regulate mitophagy in various cell types, including beta cells, and play important roles in this quality control process during metabolic reprogramming [26].

The diagram below integrates these key mechanisms into a unified signaling network.

Diagram Title: Core Signaling Network Controlling the Pluripotent Metabolic State

Quantitative Assessment of Metabolic Parameters

Tracking metabolic parameters is essential for validating the pluripotent state and evaluating the efficiency of reprogramming or differentiation protocols. The following table summarizes key quantitative metrics and the techniques used to assess them.

Table 2: Key Metabolic Parameters and Assays in Pluripotency Research

| Parameter | Technical Assay/Method | Observation in Pluripotent State vs. Somatic Cell |

|---|---|---|

| Extracellular Acidification Rate (ECAR) | Seahorse XF Glycolysis Stress Test | Significantly Higher in PSCs, indicating elevated glycolytic flux [32] |

| Oxygen Consumption Rate (OCR) | Seahorse XF Mito Stress Test | Lower in PSCs, indicating reduced reliance on OXPHOS [32] |

| Lactate Production | Colorimetric/Fluorometric assay of culture medium | Markedly Increased in PSCs [26] [27] |

| Glucose Consumption | Colorimetric assay (e.g., Glucose Uptake Assay Kit) | Markedly Increased in PSCs [27] |

| ATP Production Rate | Luciferase-based assay, Seahorse XF ATP Rate Assay | Shift in source: majority from Glycolysis in PSCs vs. OXPHOS in somatic cells [26] |

| Mitochondrial Membrane Potential (ΔΨ) Flow Cytometry | Flow Cytometry with TMRE/JC-1 dye | Variable reports; can be lower or hyperpolarized; a predictive indicator of differentiation potential [26] |

| mtDNA Copy Number | Quantitative PCR (qPCR) against mtDNA vs. nuclear DNA | Lower in PSCs, increases upon differentiation [26] [32] |

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Metabolic Control

Protocol: Metabolic Analysis of Reprogramming Intermediates using the Seahorse XF Analyzer

This protocol outlines the procedure for performing a real-time metabolic flux analysis to track the glycolytic shift during iPSC generation.

- Objective: To measure the dynamic changes in glycolysis and mitochondrial respiration during somatic cell reprogramming to iPSCs.

- Principle: The Seahorse XF Analyzer simultaneously measures the Oxygen Consumption Rate (OCR, an indicator of OXPHOS) and the Extracellular Acidification Rate (ECAR, a proxy for glycolytic lactate production) in live cells.

- Workflow:

Diagram Title: Metabolic Flux Analysis Workflow for Reprogramming

- Detailed Steps:

- Cell Seeding: Seed wild-type and experimental (e.g., Fahd1-KO [32]) murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) onto a Seahorse XF cell culture microplate coated with an appropriate substrate (e.g., 0.1% gelatin). Optimize cell density to achieve 80-90% confluence at the time of the assay to ensure a tight monolayer.

- Reprogramming Induction: Initiate reprogramming using the method of choice (e.g., retroviral transduction with Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc [32]). Include non-reprogrammed control cells.

- Assay Preparation: On the day of the assay (e.g., days 4, 8, and 12 post-induction), replace the culture medium with XF base medium (e.g., DMEM, pH 7.4) supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine. Incubate the cell culture microplate in a non-CO2 incubator for 45-60 minutes to allow temperature and pH equilibration.

- Glycolysis Stress Test: Load the XF Glycolysis Stress Test kit compounds (Glucose, Oligomycin, and 2-Deoxy-D-glucose) into the injection ports of the sensor cartridge. The assay run will sequentially measure:

- Basal ECAR.

- Glycolytic Capacity after glucose injection.

- Maximal Glycolytic Capacity after ATP synthase inhibition by oligomycin.

- Non-glycolytic acidification after shutdown of glycolysis by 2-DG.

- Data Analysis: Normalize the recorded ECAR and OCR values to total protein content (e.g., via BCA assay) per well. Calculate key parameters: Glycolysis (Glucose response), Glycolytic Capacity (Oligomycin response), and Glycolytic Reserve.

Protocol: Assessing Mitochondrial Clearance via Mitophagy during Reprogramming

This protocol describes a method to monitor mitophagy, a key process in mitochondrial remodeling.

- Objective: To visualize and quantify the activation of mitophagy during the early stages of somatic cell reprogramming.

- Principle: A fluorescent reporter protein (e.g., mt-Keima) that exhibits a pH-dependent excitation shift is targeted to the mitochondrial matrix. In neutral pH (healthy mitochondria), it is excited at ~440 nm. Upon delivery to acidic lysosomes (during mitophagy), it is excited at ~550 nm, allowing for quantification via confocal microscopy or flow cytometry.

- Detailed Steps:

- Reporter Introduction: Stably transduce somatic cells (e.g., MEFs) with a lentivirus encoding the mt-Keima reporter. Select and expand positive clones.

- Reprogramming Induction: Initiate reprogramming in the mt-Keima expressing cells.

- Monitoring and Quantification: At defined time points (e.g., days 0, 2, 4, 6 post-induction), analyze cells.

- Confocal Microscopy: Image live cells using a confocal microscope with 440 nm and 550 nm excitation lasers and collect emission at ~620 nm. Co-localization of the 550 nm-excited signal with lysosomal markers (e.g., LAMP1) confirms mitophagy. An increase in the 550/440 nm fluorescence ratio indicates enhanced mitophagic flux.

- Flow Cytometry: Analyze cells using a flow cytometer equipped with 405 nm and 561 nm lasers. The ratio of fluorescence in the 561/405 nm channels provides a quantitative measure of mitophagy for a large cell population. The use of autophagy inhibitors (e.g., Bafilomycin A1) can confirm the specificity of the signal.

- Key Reagents:

- mt-Keima plasmid (e.g., Addgene #72342)

- Polybrene or other transduction enhancers

- Selection antibiotic (e.g., Puromycin)

- Bafilomycin A1 (for inhibition control)

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolic and Mitochondrial Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Target | Example Use in Pluripotency Research |

|---|---|---|

| 2-Deoxy-D-Glucose (2-DG) | Competitive inhibitor of hexokinase, blocks glycolysis | Inhibiting glycolysis to test its necessity for reprogramming efficiency and pluripotency maintenance [27]. |

| Rapamycin | mTOR complex inhibitor, induces autophagy/mitophagy | Enhancing iPSC reprogramming efficiency by promoting mitochondrial cleanup [26]. |

| Oligomycin | ATP synthase inhibitor, blocks OXPHOS | Measuring maximal glycolytic capacity in a Seahorse assay; forcing cells to rely on glycolysis. |

| MitoTracker Probes | Cell-permeable dyes that stain active mitochondria (ΔΨ-dependent) | Visualizing mitochondrial mass, membrane potential, and network morphology via fluorescence microscopy [26] [30]. |

| TMRE / JC-1 Dyes | Fluorescent potentiometric dyes for ΔΨ | Quantifying mitochondrial membrane potential by flow cytometry or fluorescence microscopy [26]. |

| Retroviral Vectors (OSKM) | Delivery of reprogramming factors | Standard method for generating integration-prone iPSCs from somatic cells [32]. |

| Sendai Virus Vectors (OSKM) | Non-integrating RNA viral vector for factor delivery | Generating integration-free iPSCs for clinical applications. |

| 2i/LIF Medium | Contains MEK inhibitor (PD0325901) & GSK3 inhibitor (CHIR99021) + LIF | Maintaining mouse ESCs/iPSCs in a naive ground state of pluripotency for metabolic studies [30]. |

| Seahorse XF Glycolysis/Mito Stress Test Kits | Pre-configured reagent kits for metabolic flux analysis | Quantifying real-time glycolytic and oxidative function in live PSCs [32]. |

The metabolic control of pluripotency, characterized by a definitive glycolytic shift and extensive mitochondrial reprogramming, is a cornerstone of stem cell biology. This active process, driven by core pluripotency factors and fine-tuned by key signaling pathways like the PKCλ/ι-HIF1α-PGC1α axis, is not merely correlative but causative in establishing and maintaining the pluripotent state. The experimental frameworks and tools detailed herein provide a roadmap for researchers to dissect these mechanisms further. Advancing our understanding of this metabolic nexus will be instrumental in overcoming current challenges in iPSC technology, such as low reprogramming efficiency and functional maturation of differentiated progeny, thereby accelerating the development of robust models for drug discovery and safe, effective cell-based therapies.

{end of main content}

The regulation of the cell cycle, particularly the G1 phase, is a fundamental mechanism underpinning the unique capacities of embryonic stem cells (ESCs) for unlimited self-renewal and pluripotency. Unlike somatic cells, ESCs exhibit a strikingly abbreviated G1 phase, which is not merely a consequence of rapid proliferation but is actively implicated in maintaining an undifferentiated state [33] [34]. This truncated G1 phase is governed by a specialized regulatory network that minimizes the window of opportunity for differentiation signals to act, thereby reinforcing pluripotency [35]. The core pluripotency transcription factors, including OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG, are now understood to perform dual roles, directly influencing the expression of key cell cycle regulators to facilitate this rapid progression [35]. This in-depth review synthesizes current mechanistic understanding of G1 phase control in ESCs, detailing the molecular players, experimental methodologies for its study, and its critical role in the transition from pluripotency to lineage commitment, providing a critical resource for researchers and drug development professionals in the field of regenerative medicine.

Distinct Cell Cycle Features of Embryonic Stem Cells

Embryonic stem cells possess a characteristic cell cycle structure that is a functional hallmark of their pluripotent identity. The most prominent feature is a significantly shortened G1 phase and a prolonged S phase, resulting in a cell cycle profile where S-phase cells can constitute 60-70% of the population, while G1 phase cells account for only 15-20%—a stark inversion of the cycle observed in somatic cells [34]. In human ESCs (hESCs), the G1 phase is approximately 3 hours, compared to about 10 hours in a typical somatic cell [33]. This rapid cycling is crucial for the exponential expansion of the pluripotent cell pool during the initial stages of embryonic development [34].

The abbreviated G1 phase acts as a developmental barrier; the expression of lineage-specific genes and the establishment of bivalent chromatin domains at developmental gene promoters occur predominantly during G1, making it a "sensitive period" for differentiation cues [34] [35]. By shortening this phase, ESCs limit their exposure to inductive signals, thereby maintaining their undifferentiated state. Consequently, the lengthening of G1 phase is one of the earliest correlative and causative events associated with the onset of differentiation [33] [34].

Table 1: Comparative Cell Cycle Profiles of Pluripotent Stem Cells and Somatic Cells

| Cell Cycle Feature | Mouse/Human ESCs | Somatic Cells | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| G1 Phase Duration | ~2.5 - 4 hours [33] [35] | ~10 hours or more [33] | Limits exposure to differentiation signals [34] |

| S Phase Proportion | 60-70% of population [34] | Lower proportion | Supports rapid genome replication |

| RB Pathway Activity | Compromised; RB hyperphosphorylated [35] | Active; regulates G1/S restriction point | Permits constitutive S-phase entry [35] |

| CIP/KIP CKI Expression | Low (p21, p27) [33] [34] | Variable, can be high | Sustains high CDK activity for G1/S progression [34] |

| Cell Cycle Checkpoints | Relaxed DNA damage checkpoints [33] | Stringent | Favors proliferation over repair |

Core Molecular Machinery Governing G1/S Transition

The rapid traversal of the G1 phase and the transition into S-phase in ESCs are driven by a unique configuration of the core cell cycle engine, centered on Cyclin-CDK complexes and their inhibitors.

Constitutive Cyclin-CDK Activity

ESCs exhibit constitutively high activity of G1/S Cyclin-CDK complexes. A non-cyclic expression of cyclins contributes to precocious CDK activity, leading to the hyperphosphorylation and inactivation of the retinoblastoma protein (RB) [35]. Unlike in somatic cells, where hypo-phosphorylated RB binds and inhibits E2F transcription factors, ESCs maintain RB in a hyper-phosphorylated state, allowing for constitutive E2F activity and the unabated expression of genes required for DNA replication and S-phase entry [35]. The low overall expression level of RB in naive ESCs further reduces the threshold of CDK activity needed to trigger the G1/S transition [35].

Suppression of Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Inhibitors (CKIs)

The expression of the two major families of CKIs is actively suppressed in ESCs. The CIP/KIP family (p21, p27, p57) is typically expressed at low levels in naive-state ESCs, which helps sustain high CDK2 activity [34]. This repression is mediated by ESC-specific microRNAs and nonsense-mediated decay [35]. The levels of p21 and p27 increase upon differentiation, inhibiting Cyclin E-CDK2 complexes, lengthening G1, and promoting the acquisition of a differentiated fate [33] [34]. Similarly, the INK4 family (e.g., p16) is generally not expressed, preventing inhibition of CDK4/6 [34].

Table 2: Key Cell Cycle Regulators and Their Roles in ESCs

| Regulator | Family/Type | Expression/Activity in ESCs | Primary Function in G1/S Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| RB | Pocket Protein | Hyperphosphorylated & low total level [35] | Inactive; allows constitutive E2F activity for S-phase entry |

| p21 / p27 | CIP/KIP CKI | Low expression [33] [34] | Relief of inhibition on Cyclin E/A-CDK2 complexes |

| Cyclin E / A | G1/S Cyclin | Constitutively high expression/activity [35] | Drives phosphorylation of RB and replication machinery |

| CDK2 | CDK | Constitutively active [34] | Key kinase for G1/S progression; targeted by p21/p27 |

| E2F | Transcription Factor | Constitutively active [35] | Transcribes S-phase genes |

Interplay Between Pluripotency Network and Cell Cycle

The core pluripotency factors OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG are not passive beneficiaries of the rapid cell cycle but are active architects of it. They form a network that directly and indirectly regulates the expression of cell cycle genes to reinforce the abbreviated G1 phase.

- OCT4 influences G1 progression by regulating the expression of long non-coding RNAs (lincRNAs) and microRNAs that target cell cycle inhibitors, thereby promoting S-phase entry [35].

- SOX2 has been shown to directly promote the expression of cyclins and also to regulate the expression of the CKI p21 (Cdkn1a), further facilitating rapid cycling [35].

- NANOG contributes to G1/S progression by upregulating positive regulators such as CDK6 and CDC25 phosphatases, and downregulating inhibitors like CDKN1C (p57) [35].

This coupling creates a positive feedback loop: the rapid cell cycle helps maintain the pluripotent state by limiting time for differentiation, while the pluripotency network actively sustains the rapid cell cycle. This interconnection means that perturbations in the pluripotency network often lead to cell cycle remodeling, and vice-versa.

Figure 1: Coupling of the Core Pluripotency Network with G1/S Phase Control. The core pluripotency transcription factors OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG directly promote a shortened G1 phase by suppressing CDK inhibitors and sustaining RB hyperphosphorylation. The resulting abbreviated G1 phase, in turn, helps maintain pluripotency by limiting the time available for cells to respond to differentiation signals, creating a reinforcing loop.

Critical Signaling Pathways Shaping the G1 Phase

Extracellular signaling pathways, which are instrumental in defining pluripotency states, exert significant control over the G1 phase duration by interfacing with the core cell cycle machinery.

- FGF/ERK Signaling: This pathway is a key promoter of G1-phase progression. Its activation leads to elevated CDK/cyclin activity. Notably, inhibition of MEK1/2 (the kinase upstream of ERK) in naive ESCs increases the G1 phase duration, demonstrating its critical role in maintaining the rapid cycle [36] [35]. MEK1/2 inhibition can lead to stabilization of p53, which further contributes to G1 lengthening [36].

- WNT Signaling: The WNT pathway also promotes G1/S progression, primarily through the transcriptional upregulation of cyclins D and E [35]. This places WNT as another developmental signaling pathway co-opted in ESCs to regulate proliferation.

- LIF/JAK-STAT3 Signaling: The Leukemia Inhibitory Factor (LIF) signal, crucial for maintaining mouse ESC self-renewal, acts through JAK-STAT3. This pathway helps maintain the expression of the core pluripotency network and, by extension, its cell cycle targets. Recent studies have identified Src homology 2 domain-containing phosphatase-2 (SHP-2) as a negative regulator of STAT3 phosphorylation, and its inhibition promotes pluripotency maintenance [37].

Experimental Models and Methodologies for Analysis

Investigating the unique G1 phase of ESCs requires a combination of sophisticated cell cycle reporters, precise synchronization methods, and high-resolution imaging techniques.

Key Methodologies

- Fluorescent Ubiquitination-based Cell Cycle Indicator (FUCCI) System: This powerful technology utilizes cell cycle phase-specific proteolysis to label nuclei in G1 phase (e.g., with red fluorescence from Cdt1-mCherry/mKO2) and S/G2/M phases (e.g., with green fluorescence from Geminin-GFP) [38]. It allows for real-time visualization and tracking of the G1 phase in live cells.

- Cell Cycle Synchronization: Researchers use chemical inhibitors to obtain populations enriched in specific phases. For example, thymidine or aphidicolin (an inhibitor of DNA polymerase) can be used to block cells at the G1/S boundary, allowing for the study of synchronous progression upon release [39].

- Intravital Live-Cell Imaging: Advanced microscopy techniques enable the tracking of stem cell growth and division in living tissues (e.g., mouse epidermis or zebrafish models), providing data on cell size, cycle phase duration, and division dynamics in a physiologically relevant context [38].

- EdU/BrdU Pulse-Chase Assays: Incorporation of thymidine analogs like 5-ethynyl-2'-deoxyuridine (EdU) during S-phase, followed by a chase period, allows for precise measurement of S-phase duration and the timing of subsequent mitoses to calculate G2 phase length [39].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying G1 Phase in ESCs

| Reagent / Tool | Category | Key Function in G1 Phase Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| FUCCI Reporters | Fluorescent Reporter | Visualizes G1 (red) vs. S/G2/M (green) phases in live cells [38] | Real-time tracking of G1 duration and exit in single cells. |

| MEK1/2 Inhibitors (e.g., PD0325901) | Small Molecule Inhibitor | Lengthens G1 phase by inhibiting pro-proliferative ERK signaling [36] [35] | Probing the link between signaling and cell cycle; promoting naive pluripotency. |

| Aphidicolin | Chemical Synchronizer | Reversibly inhibits DNA synthesis, arresting cells at G1/S boundary. | Synchronizing ESC populations for phase-specific biochemical analysis. |

| EdU / BrdU Kits | Nucleotide Analog | Labels and detects cells in S-phase via click chemistry or immunofluorescence. | Quantifying S-phase fraction; pulse-chase experiments to measure phase lengths [39]. |

| Anti-pRB Antibodies | Antibody | Detects phosphorylation status of RB (hyper vs. hypo-phosphorylated). | Assessing activity of the RB pathway and CDK activity in ESCs [35]. |

| Kinetin & Riboside (MOP-1) | Novel Nanomaterial | A vanadium-based metal-organic polyhedra that mimics LIF activity to maintain pluripotency [37]. | Alternative to unstable protein factors for long-term ESC culture. |

Figure 2: A Generalized Experimental Workflow for Analyzing G1 Phase Dynamics. A typical protocol begins with synchronization of an ESC population at the G1/S boundary using a reversible inhibitor like aphidicolin. Upon release, cells progress synchronously through the cycle, allowing researchers to monitor G1 duration in real-time using FUCCI reporters or to harvest cells at specific intervals for biochemical and molecular analyses like immunoblotting, flow cytometry, and gene expression profiling.

The G1 Phase in Differentiation and Therapeutic Applications

The transition from pluripotency to lineage commitment is marked by a fundamental remodeling of the cell cycle, beginning with a lengthening of the G1 phase. This is not a passive consequence but an active prerequisite for differentiation. The prolongation of G1 provides the necessary time for the activation of lineage-specific genes and the extensive chromatin remodeling required for cell fate commitment [33] [35].

Furthermore, recent research has highlighted the importance of other cell cycle phases in differentiation. For instance, a G2 cell cycle pause has been identified as obligatory for the differentiation of hESCs into endodermal and mesodermal lineages [33]. This underscores that cell cycle regulation in stem cell fate decisions is not confined to G1 but involves phase-specific checkpoints throughout the cycle.

From a therapeutic perspective, controlling the ESC cell cycle is crucial for directed differentiation protocols aimed at generating specific somatic cell types for regenerative medicine and drug screening. Manipulating the duration of G1 phase, for example by modulating MEK/ERK signaling, could enhance the efficiency and homogeneity of differentiation outcomes. Furthermore, understanding the cell cycle's role in somatic cell reprogramming to induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) is vital, as the process requires a dramatic shortening of the G1 phase, reminiscent of the ESC state [34]. Overcoming the barriers imposed by the somatic cell cycle is a key challenge in improving reprogramming efficiency.

Reprogramming Technologies and Therapeutic Applications in Disease Modeling

The discovery that somatic cell identity is not terminal but can be reset to a pluripotent state has fundamentally transformed regenerative medicine and developmental biology research. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of the two predominant reprogramming methodologies: transcription factor-mediated induction using Yamanaka factors and emerging chemical reprogramming using fully defined small molecule cocktails. We examine the molecular mechanisms, transcriptional dynamics, and epigenetic remodeling events inherent to each approach, highlighting the distinct technical advantages and experimental considerations for research applications. Detailed protocols for implementing these technologies are presented alongside comprehensive reagent solutions, enabling researchers to select appropriate strategies for disease modeling, drug screening, and therapeutic development.

The conceptual foundation for induced pluripotency emerged from challenging the long-standing dogma that cellular differentiation was a unidirectional process. Conrad Waddington's iconic 1957 "epigenetic landscape" metaphor depicted differentiation as a ball rolling downhill into increasingly irreversible valleys of specialization [40] [41]. This paradigm was first fundamentally challenged by John Gurdon's seminal somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) experiments in 1962, which demonstrated that an oocyte could reprogram a differentiated somatic nucleus to support embryonic development [40]. These experiments revealed that cellular identity was maintained through reversible epigenetic mechanisms rather than irreversible genetic changes.

The field advanced significantly with the isolation of embryonic stem cells (ESCs) from mouse embryos in 1981 and human embryos in 1998 [40]. Researchers observed that fusion between ESCs and somatic cells resulted in hybrid cells with pluripotent characteristics, suggesting that ESCs contained dominant factors capable of reprogramming somatic nuclei [42] [40]. This insight culminated in the landmark discovery by Shinya Yamanaka and Kazutoshi Takahashi in 2006 that retroviral introduction of four transcription factors—Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc (collectively termed OSKM or Yamanaka factors)—could reprogram mouse fibroblasts into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [43] [40]. This finding demonstrated that pluripotency could be induced without embryos or SCNT, offering an unprecedented platform for disease modeling and regenerative medicine. The subsequent confirmation in 2007 that human somatic cells could similarly be reprogrammed opened new avenues for patient-specific cell therapies [43] [40].

Molecular Mechanisms of Pluripotency Induction

Core Transcriptional Network and Regulatory Dynamics