Oncogenic Potential in Stem Cells: Assessment Strategies and Risk Mitigation for Research and Therapy

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of oncogenic risk assessment across diverse stem cell types, including pluripotent stem cells (PSCs), induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), and adult stem cells.

Oncogenic Potential in Stem Cells: Assessment Strategies and Risk Mitigation for Research and Therapy

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of oncogenic risk assessment across diverse stem cell types, including pluripotent stem cells (PSCs), induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), and adult stem cells. It explores the fundamental biological mechanisms driving tumorigenicity, details current and emerging methodologies for risk evaluation, addresses key challenges in safety profiling, and presents comparative frameworks for validating assessment strategies. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes the latest advances in the field to inform safer therapeutic development and more robust preclinical screening protocols.

Understanding the Roots of Risk: Stem Cell Biology and Tumorigenic Mechanisms

Stem cells represent a cornerstone of regenerative medicine due to their unique capacities for self-renewal and differentiation. However, these very properties are also hallmarks of cancer, creating a critical challenge for therapeutic development. The oncogenic potential—the ability to initiate tumor formation—varies significantly across different stem cell types and is influenced by distinct molecular mechanisms. Understanding these differences is paramount for advancing safe and effective stem cell-based therapies. This guide provides a systematic comparison of the oncogenic risk profiles of three major stem cell categories: pluripotent stem cells (PSCs), including both embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), and adult stem cells (ASCs). For researchers and drug development professionals, this comparison is essential for making informed decisions about model system selection, risk mitigation strategies, and clinical translation pathways.

Comparative Oncogenic Risk Profiles of Major Stem Cell Types

Table 1: Oncogenic Risk Profile by Stem Cell Type

| Stem Cell Type | Key Oncogenic Risks | Primary Tumor Types | Contributing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) | - Teratoma formation from undifferentiated cells- Malignant transformation from partially reprogrammed cells- Reactivation of reprogramming factors (e.g., c-Myc) [1] | Teratomas, somatic tumors | Genomic integration of vectors, oncogenic transgenes, incomplete reprogramming, epigenetic aberrations [2] [1] |

| Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) | - Teratoma formation from residual undifferentiated cells [1] | Teratomas | Spontaneous differentiation, genomic instability during long-term culture |

| Adult Stem Cells (ASCs) / Cancer Stem Cells (CSCs) | - Initiation of primary tumors- Therapy resistance and cancer recurrence [3] | Carcinomas, leukemias, solid tumors | Accumulated mutations in long-lived cells, aberrant niche signaling, epigenetic dysregulation [4] [3] |

Table 2: Key Molecular Drivers and Markers of Oncogenesis

| Stem Cell Type | Core Pluripotency/Ongenic Drivers | Characteristic Markers | Regulatory Pathways |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSCs (iPSCs/ESCs) | Oct4, Sox2, Nanog, c-Myc, Klf4 [1] | Alkaline Phosphatase, SSEA-4, TRA-1-60, TRA-1-81 | Wnt/β-Catenin, Myc-centered network [1] |

| Adult Stem Cells (ASCs) | Varies by tissue type | Varies by tissue (e.g., Lgr5 for intestine, CD34+CD38- for hematopoiesis) | Notch, Hedgehog, Wnt [4] |

| Cancer Stem Cells (CSCs) | Often Oct4, Sox2, Nanog (re-activated) [3] | CD44+CD24- (breast), CD133+ (brain, colon), CD34+CD38- (AML) [3] | Wnt/β-Catenin, Hedgehog, Notch, JAK/STAT [3] |

Experimental Models and Assays for Assessing Oncogenic Potential

In Vitro Transformation Assays

The oncogenic foci (OF) formation assay is a classical method to study transformation. Strikingly, the methodological parallels between OF production and iPSC generation are profound; both involve transducing fibroblasts with specific sets of genes and result in colonies with distinct morphologies [5]. Direct comparison of the transcriptomes of iPSCs and OF derived from common parental mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) revealed substantial overlap, including shared downregulation of differentiation-associated genes and upregulation of monosaccharide metabolism pathways [5]. However, a critical distinction lies in the specific activation of a 17-gene pluripotency cluster in iPSCs that is absent in OF, underscoring that while the processes are related, the cell types are distinct [5].

In Vivo Tumorigenicity Testing

The gold-standard assay for validating the pluripotency of PSCs—teratoma formation—is simultaneously a demonstration of their oncogenic potential. Upon injection into immunodeficient mice, undifferentiated PSCs form teratomas, benign tumors containing tissues from all three germ layers [1]. The risk extends beyond teratomas; studies have documented the formation of neural overgrowths and ocular tumors from transplanted human ESC-derived dopaminergic neurons and retinal progenitors in animal models [1]. To assess the tumor-initiating capacity of CSCs, researchers employ xenotransplantation models using immunodeficient mice (e.g., NOD/SCID strains). The frequency of CSCs is quantified by limiting dilution assays, which measure the cell dose required to form a tumor upon serial transplantation [3].

Molecular Mechanisms Governing Oncogenic Transformation

Shared Transcriptional Networks in Pluripotency and Cancer

A foundational link between PSCs and cancer is the shared activity of core transcriptional networks. Myc and the core pluripotency circuit (Nanog, Oct4, and Sox2) are fundamental to both pluripotency maintenance and oncogenesis, promoting self-renewal, proliferation, and resistance to differentiation [1]. Bioinformatics analyses reveal that more aggressive cancers often exhibit high expression of these core pluripotency and Myc-centered networks [1]. The ectopic expression of these factors during iPSC reprogramming, particularly the integration and potential reactivation of the potent oncogene c-Myc, presents a significant and well-documented tumorigenic risk [1].

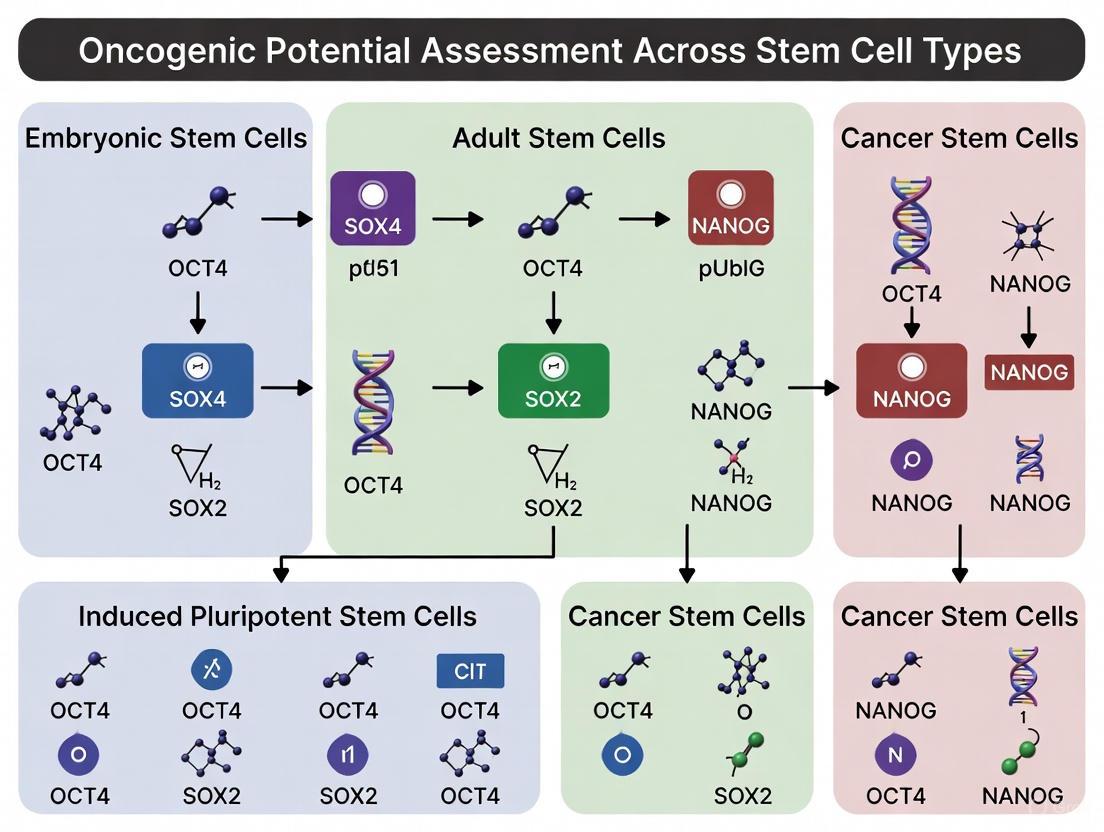

Diagram Title: Shared Transcriptional Networks in Pluripotency and Cancer

Signaling Pathways in Cancer Stem Cells and Niches

In adult tissues, CSCs and normal ASCs reside in specialized niches that regulate their behavior through key developmental signaling pathways. Disruption of this crosstalk is a common mechanism in oncogenesis. The Wnt/β-Catenin, Hedgehog, Notch, NF-κB, JAK/STAT, and TGF-β pathways are frequently dysregulated in CSCs, contributing to their maintenance, self-renewal, and therapeutic resistance [3]. The origin of CSCs is context-dependent, with evidence suggesting they can arise from normal ASCs that accumulate mutations or from more differentiated progenitor cells that re-acquire self-renewal capacity through epigenetic or mutational events [4]. The long lifespan and inherent self-renewal capacity of ASCs make them particularly susceptible to accumulating the genetic "hits" required for transformation [4].

Diagram Title: Key Pathways and CSCs

Research Reagent Solutions for Oncogenicity Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Toolkit for Oncogenic Potential Assessment

| Reagent / Tool Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Vectors | Excisable lentivirus (doxycycline-inducible), PiggyBac transposon, Sendai virus, mRNA [1] | Generating footprint-free iPSCs; minimizing genomic integration risks. |

| Cell Sorting Markers | Antibodies against CD34, CD38, CD44, CD24, CD133, ALDH activity assays [3] | Isulating and purifying putative CSCs and normal ASC populations for functional study. |

| Pathway Modulators | Small molecule inhibitors of Wnt (e.g., IWP-2), Hedgehog (e.g., cyclopamine), Notch (e.g., DAPT) [3] | Probing the functional contribution of specific signaling pathways to stem cell maintenance and transformation. |

| In Vivo Models | Immunodeficient mice (e.g., NOD/SCID, NSG) | Conducting teratoma and tumorigenicity assays via xenotransplantation. |

The landscape of oncogenic potential across stem cell types is complex and multifaceted. PSCs, particularly iPSCs, carry a significant risk of teratoma formation and transformation driven by their core pluripotency networks and the technical challenges of reprogramming. In contrast, the primary risk associated with ASCs is their susceptibility to serve as the cell of origin for cancers over time due to their longevity. The emergence of CSCs across numerous malignancies presents a major therapeutic challenge in oncology, driving disease recurrence and resistance.

Future progress hinges on continued refinement of safety measures. For iPSCs, this includes the adoption of non-integrating reprogramming methods, advanced purification techniques to remove undifferentiated cells (e.g., fluorescence-activated cell sorting using pluripotency surface markers), and the development of "suicide genes" as a safety switch in cell therapies [1]. In the realm of CSCs, the focus is on identifying novel, specific surface markers and understanding the dynamic plasticity that allows non-CSCs to re-acquire stem-like properties, paving the way for more effective combinatorial therapies that can prevent relapse [3]. A deep understanding of these distinct oncogenic risk profiles is indispensable for guiding the safe clinical application of stem cell technologies and for developing novel, curative strategies against cancer.

The therapeutic promise of stem cells in regenerative medicine is underpinned by three core mechanistic properties: self-renewal, differentiation capacity, and genetic stability. These interdependent functions determine both the therapeutic potential and the inherent oncogenic risks of any stem cell population. Self-renewal refers to the ability of a stem cell to divide and produce identical copies of itself, thereby maintaining the stem cell pool throughout life. Differentiation capacity (potency) defines the range of specialized cell types a stem cell can generate, ranging from pluripotent (all embryonic lineages) to multipotent (limited to tissue-specific lineages). Genetic stability ensures the faithful transmission of genomic information during cell division, preventing the accumulation of mutations that could lead to malignant transformation [6] [7].

The precise regulation of self-renewal pathways is critical, as their dysregulation is a hallmark of cancer. Cancer stem cells (CSCs), a subpopulation within tumors, co-opt these same pathways to drive tumor initiation, maintenance, metastasis, and therapy resistance. Consequently, a comparative assessment of these core mechanisms across stem cell types is not merely an academic exercise but a fundamental prerequisite for evaluating their therapeutic safety profile and oncogenic potential [8] [9].

Self-Renewal Pathways: Mechanisms and Dysregulation

Self-renewal in stem cells is governed by a set of evolutionarily conserved signaling pathways. In normal stem cells, these pathways are tightly regulated; however, in CSCs, they are often deregulated, leading to unchecked proliferation.

Key Signaling Pathways in Self-Renewal

The principal pathways governing stem cell self-renewal include Hedgehog (Hh), Wnt, Notch, and the B-cell-specific moloney murine leukemia virus integration site 1 (BMI1) pathway [9].

- Hedgehog (Hh) Pathway: In the absence of the Hh ligand, the Patched (Ptc) receptor inhibits Smoothened (Smo), preventing activation of the Gli transcription factors. Upon Hh binding, this inhibition is relieved, leading to Gli-mediated transcription of target genes (e.g., cyclins) that promote self-renewal. This pathway is crucial in CSCs of cancers like basal cell carcinoma, leukemia, and pancreatic cancer [9].

- Wnt Pathway: In a canonical Wnt-off state, a destruction complex targets β-catenin for degradation. Wnt signaling stabilizes β-catenin, allowing its translocation to the nucleus to activate genes like c-MYC and CYCLIN D1, which drive proliferation and self-renewal. Aberrant Wnt signaling is implicated in various CSCs [9].

- Notch Pathway: Notch signaling is initiated by ligand-receptor (e.g., Delta, Jagged) interaction between adjacent cells. This triggers proteolytic cleavage of the Notch intracellular domain (NICD), which translocates to the nucleus and activates target genes such as Hairy and enhancer of split (HES) family members. Dysregulated Notch signaling contributes to T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) and breast CSCs [9].

- Transcriptional Networks in Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC): A specific bi-stable network involving PITX1, SOX2, and TP63 promotes self-renewal and suppresses differentiation in SCC. PITX1 and SOX2, which are epigenetically repressed in normal skin, become expressed in SCC tumor-propagating cells (TPCs). They cooperatively bind enhancers to activate pro-proliferation genes and repress the differentiation factor KLF4, maintaining the TPC state [10].

The following diagram illustrates the core logic of these self-renewal pathways and their frequent dysregulation in CSCs.

Comparative Self-Renewal Mechanisms Across Stem Cell Types

Different stem cell types exhibit distinct self-renewal behaviors and regulatory mechanisms, which directly influence their oncogenic potential. The following table compares these aspects across major stem cell categories.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Self-Renewal and Oncogenic Risk Across Stem Cell Types

| Stem Cell Type | Self-Renewal Capacity | Key Regulatory Pathways & Factors | Oncogenic Potential & Associated Risks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) [6] [11] | High, unlimited self-renewal in vitro; pluripotent. | Oct4, Nanog, Sox2; dependent on specific growth factors (FGF, TGF-β). | High teratoma risk in vivo due to pluripotency; requires precise pre-differentiation [11] [7]. |

| Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) [6] | High, similar to ESCs; pluripotent. | Reprogramming factors (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc); same pathways as ESCs. | Risk from reprogramming methods (e.g., viral integration); potential for epigenetic abnormalities [6]. |

| Adult/Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) [6] [12] | Limited in vitro expansion; multipotent. | Microenvironment (niche) dependent; express CD73, CD90, CD105. | Lower tumorigenicity; primary risk is genomic instability during long-term culture [7] [12]. |

| Hematopoietic Stem Cells (HSCs) [6] [13] | Lifelong, balanced self-renewal and differentiation. | Tightly regulated by bone marrow niche; transcription factors (EVI1). | Imbalance linked to hematological malignancies; aging increases self-renewal bias [13]. |

| Cancer Stem Cells (CSCs) [8] [9] | Deregulated, excessive self-renewal. | Dysregulated Hh, Wnt, Notch, BMI1; SCC-specific: PITX1-SOX2-TP63 network [10]. | Directly drives tumorigenesis, metastasis, and therapy resistance. |

Assessing Differentiation Capacity and Genetic Stability

The differentiation potential of a stem cell is a double-edged sword, offering regenerative capability while posing a risk of uncontrolled growth if differentiation fails.

Differentiation Capacity and Its Therapeutic Implications

- Pluripotency and Lineage Specification: ESCs and iPSCs can differentiate into derivatives of all three embryonic germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, endoderm), making them powerful for disease modeling and generating diverse cell types for therapy. However, this broad potential necessitates rigorous in vitro differentiation protocols to ensure no undifferentiated cells remain in therapeutic products, as these can cause teratomas [6] [11].

- Multipotency and Tissue Repair: Adult stem cells, including MSCs and HSCs, are multipotent, with differentiation restricted to lineages of their tissue of origin. MSCs can differentiate into osteoblasts, chondrocytes, and adipocytes, and their therapeutic effect is largely mediated via paracrine signaling and immunomodulation, reducing the risk of aberrant differentiation [6] [12].

- Blocked Differentiation in Cancer: A hallmark of CSCs is their ability to self-renew excessively while failing to undergo terminal differentiation. The PITX1-SOX2-TP63 network in SCCs, for example, actively suppresses the differentiation factor KLF4, locking cells in a proliferative, stem-like state [10].

Genetic Stability Assessment and Protocols

Maintaining genetic integrity is paramount for safe clinical application. The following experimental protocols are central to biosafety assessment.

- Karyotyping and Genetic Analysis: This is a standard method for detecting gross chromosomal abnormalities (e.g., aneuploidy, translocations) that may arise during long-term culture of stem cells like ESCs and iPSCs. It involves arresting cells in metaphase, staining the chromosomes, and analyzing their number and structure [7].

- In Vivo Tumorigenicity Assay: This is the definitive test for assessing the potential of a stem cell product to form tumors. The protocol involves immunocompromised mice (e.g., NOD/SCID) [7] [8].

- Cell Preparation: The stem cell product is prepared at the intended clinical dose and higher doses.

- Administration: Cells are implanted into mice via a clinically relevant route (e.g., subcutaneous, intramuscular).

- Observation: Animals are monitored for an extended period (e.g., 6 months) for signs of tumor formation.

- Necropsy and Histopathology: At the endpoint, the implantation site and major organs are examined grossly and microscopically for any neoplastic growths or teratomas.

- Oncogenicity/Teratogenicity Testing: This assesses the potential of cells, particularly pluripotent ones, to cause tumors or disruptive embryonic growth. It uses a combination of in vitro methods and in vivo models in immunocompromised animals, evaluating the formation of complex, disorganized tissues indicative of teratoma formation [7].

The workflow for a comprehensive biosafety assessment integrates multiple of these experimental approaches, as shown below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Research Solutions

Advancing research in stem cell self-renewal and oncogenic potential requires a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details essential solutions for key experimental workflows.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Stem Cell and CSC Mechanism Studies

| Research Reagent / Tool | Primary Function in Research | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Small Molecule Pathway Inhibitors [9] | Chemically inhibit key self-renewal pathway components (e.g., Smo for Hh, γ-secretase for Notch). | Functional validation of pathway necessity in CSCs; target identification for therapeutic development. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems [6] | Enable precise genome editing for gene knockout, knock-in, or mutation. | Functional screens to identify self-renewal genes; introduce or correct oncogenic mutations; generate disease models. |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies (CD44, CD133, CD73, CD90, CD105) [8] [12] | Identify and isolate specific stem cell and CSC populations based on surface marker expression. | Phenotypic characterization; purification of homogeneous cell populations for functional assays. |

| scRNA-Seq Kits [6] [8] | Profile gene expression at single-cell resolution. | Deconvolute intra-tumor heterogeneity; identify rare CSC subpopulations; trace lineage commitment. |

| 3D Organoid Culture Systems [8] | Provide a more physiologically relevant, three-dimensional environment for cell growth. | Model tumor-stroma interactions; study CSC dynamics and drug response ex vivo. |

The path from bench to bedside for stem cell therapies is fraught with the challenge of harnessing potent self-renewal and differentiation capacities while mitigating oncogenic risks. A direct comparison reveals that pluripotent cells (ESCs, iPSCs) offer unparalleled therapeutic potential but carry the highest inherent risk of teratoma formation, demanding stringent pre-differentiation and genetic stability checks. In contrast, adult stem cells like MSCs present a lower tumorigenic risk but have limited expansion and differentiation potential. The most critical insight is that the very pathways essential for normal stem cell function—Hedgehog, Wnt, and Notch—are the ones most frequently subverted by CSCs to drive malignancy [6] [9].

Therefore, a rigorous, multi-parametric biosafety assessment is non-negotiable. This includes comprehensive product quality control (sterility, identity, potency), validated tumorigenicity assays in sensitive models, and long-term genetic stability monitoring [7]. Emerging tools like AI-driven multi-omics analysis [8] and proteomic-based stemness indices [14] promise more refined risk stratification. The future of safe and effective stem cell-based therapies lies in an integrated approach that continuously evaluates the delicate balance between regenerative potential and oncogenic danger across all stages of product development.

Cancer Stem Cells (CSCs) represent a functionally distinct subpopulation within tumors that possess the capacity to drive tumor initiation, progression, metastasis, and therapeutic resistance. According to the CSC hypothesis, only a small subset of cancer cells has the ability to recapitulate the formation of a growing tumor [15]. These cells share critical properties with normal stem cells, most notably long-term self-renewal capacity and the ability to differentiate into heterogeneous cancer cell lineages that comprise the tumor bulk [15] [8]. The concept that stemness plays a dual role in both initiating and maintaining tumors has fundamentally transformed our understanding of oncogenesis and presents crucial implications for therapeutic development.

The CSC model contrasts with earlier stochastic models of cancer development, which proposed that most cancer cells possess similar tumorigenic potential [15]. Instead, accumulating evidence supports a hierarchical organization in many tumors, with CSCs sitting at the apex and driving the production of more differentiated daughter cells with limited proliferative potential [15] [8] [16]. This paradigm shift necessitates a reevaluation of oncogenic potential assessment across stem cell types and demands therapeutic strategies that specifically target the CSC population to achieve durable remission and prevent recurrence.

Biological Foundations of Cancer Stem Cells

Historical Context and Theoretical Evolution

The conceptual foundations of CSCs extend back to the 19th century with Rudolf Virchow's dictum "omnis cellula e cellula" (every cell from a cell) and Julius Cohnheim's "embryonal rest hypothesis," which proposed that tumors arise from residual embryonic cells persisting in adult tissues [8]. Modern CSC theory gained substantial experimental support in 1994-1997 with John Edgar Dick's groundbreaking work identifying SCID-leukemia-initiating cells (SL-ICs) in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) characterized by a CD34⁺CD38⁻ phenotype [8]. This established that only a specific cellular subpopulation possessed leukemia-initiating potential, providing the first rigorous experimental evidence for the CSC model in human cancer [8].

Subsequent research has demonstrated that CSCs exist across diverse cancer types, including solid tumors such as glioblastoma, breast cancer, lung cancer, prostate cancer, colon cancer, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, pancreatic cancer, and melanoma [8]. The CSC hypothesis serves as a supplement rather than a replacement for conventional oncogenic theory, focusing attention on the cell type targeted by molecular events rather than questioning the events themselves [15].

Functional Properties and Defining Characteristics

CSCs are functionally defined by several hallmark characteristics that distinguish them from the bulk tumor population:

Self-Renewal Capacity: CSCs undergo extended self-renewal through mitotic division, maintaining the stem cell pool through either asymmetric or symmetric division [15]. This capacity is thought to be a determining factor in tumor maintenance and regrowth [15].

Differentiation Potential: CSCs can differentiate into the heterogeneous lineages of cancer cells that constitute the tumor, contributing to intratumoral heterogeneity [15] [8].

Therapy Resistance: CSCs demonstrate enhanced resistance to conventional therapies including chemotherapy and radiation, attributed to mechanisms such as enhanced DNA repair systems, drug efflux pumps, and quiescence [8] [17].

Metabolic Plasticity: CSCs can switch between glycolysis, oxidative phosphorylation, and alternative fuel sources such as glutamine and fatty acids, enabling survival under diverse environmental conditions [8].

Interaction with the Tumor Microenvironment: CSCs constantly interact with stromal cells, immune components, and vascular endothelial cells, facilitating metabolic symbiosis that further promotes CSC survival and drug resistance [8] [18].

Table 1: Core Functional Properties of Cancer Stem Cells

| Property | Functional Significance | Therapeutic Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Self-Renewal | Sustains long-term tumor growth and regeneration | Targeting self-renewal pathways may deplete CSC reservoir |

| Differentiation Capacity | Generates cellular heterogeneity within tumors | Differentiation therapy may reduce tumor aggressiveness |

| Therapy Resistance | Leads to treatment failure and relapse | Requires specific CSC-targeting approaches |

| Metabolic Plasticity | Adapts to nutrient deprivation and stress | Dual metabolic inhibition may overcome adaptation |

| Microenvironment Interaction | Creates protective niches | Targeting niche components may sensitize CSCs |

The Dual Role of Stemness: Initiation Versus Maintenance

Stemness in Tumor Initiation: Cellular Origins

The origin of CSCs remains a subject of ongoing investigation, with evidence supporting multiple potential cellular sources. Current research indicates that CSCs may originate from either transformed tissue-resident stem cells or de-differentiated somatic cells that reacquire stem-like properties [16]. The specific cell of origin significantly influences tumor characteristics, prognosis, and aggressiveness [16].

In hematopoietic malignancies, the cellular origin is relatively well-established. Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) typically originates from hematopoietic stem or progenitor cells [16], while chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is characterized by the Bcr-Abl oncogene resulting from chromosomal translocation between chromosomes 9 and 22 [16]. For solid tumors, the picture is more complex. Gastric cancers may arise from slow-cycling Mist1-expressing cells in the gastric corpus or Lgr5-expressing cells in the gastric antrum [16]. Breast tumors originating from luminal progenitors are generally associated with better prognosis, while those originating from basal-like progenitors display more aggressive phenotypes [16].

The transformation process involves both genetic and epigenetic alterations. Normal stem cells may require fewer genomic changes for transformation since they already possess inherent self-renewal capacity [16]. Differentiated cells, in contrast, must undergo de-differentiation and acquire self-renewal capabilities, potentially through the reactivation of embryonic programs [19]. This process shares remarkable similarities with induced pluripotency, utilizing overlapping molecular signaling and epigenetic pathways [19].

Stemness in Tumor Maintenance: Mechanisms and Pathways

Once tumors are established, stemness properties shift to maintenance functions, promoting continuous growth, fostering heterogeneity, and enabling adaptation to therapeutic pressures. Several evolutionarily conserved signaling pathways play critical roles in maintaining CSC self-renewal and survival:

- Wnt/β-catenin Signaling: Regulates self-renewal in various CSC populations and contributes to therapeutic resistance [15] [19].

- Notch Signaling: Plays essential roles in cell fate decisions and maintains CSC populations across multiple cancer types [15].

- Hedgehog (Hh) Signaling: Contributes to CSC maintenance and tissue patterning [15].

- NF-κB Pathway: Promotes inflammatory responses and supports CSC survival [15].

- BMI1 Polycomb Protein: Regulates self-renewal through epigenetic mechanisms [15].

These pathways operate within a complex regulatory network influenced by both intrinsic genetic programs and extrinsic cues from the tumor microenvironment [8] [18]. The dynamic interaction between CSCs and their niches creates specialized microenvironments that maintain stemness properties through cytokine networks, metabolic symbiosis, and physical interactions [18].

Diagram 1: Signaling Pathways Regulating CSC Stemness Properties. Multiple evolutionarily conserved pathways converge to maintain core CSC functionalities that support both tumor initiation and maintenance.

Experimental Assessment of CSCs: Methodologies and Biomarkers

CSC Identification and Isolation Techniques

Experimental assessment of CSCs relies on a combination of surface marker expression, functional assays, and transplantation models. No single marker is entirely specific for CSCs, requiring multiparameter approaches for reliable identification [15] [19]. The gold standard for validating CSC properties remains the demonstration of tumor-initiating capacity in immunodeficient mouse models, where purified cell populations are transplanted to assess their ability to recapitulate tumor heterogeneity [15].

Table 2: Key Experimental Methods for CSC Identification and Characterization

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Experimental Readouts | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Marker-Based Isolation | FACS (Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting), MACS (Magnetic-Activated Cell Sorting) | Purity of CSC populations, Marker expression profiles | Marker heterogeneity across cancer types, Dynamic expression changes |

| Functional Assays | Sphere Formation, Limiting Dilution Transplantation, Side Population Analysis | Self-renewal capacity, Tumor-initiating frequency, Drug efflux capability | Microenvironment influence, Assay stringency, Technical variability |

| Omics Profiling | Single-Cell RNA Sequencing, Proteomics, Phosphoproteomics, Glycoproteomics | Molecular signatures, Pathway activation, Heterogeneity mapping | Computational complexity, Data integration challenges |

| In Vivo Tracking | Lentiviral barcoding, Bioluminescent imaging, Lineage tracing | CSC dynamics, Clonal evolution, Metastatic patterns | Model organism limitations, Microenvironment differences |

CSC Biomarkers Across Cancer Types

Biomarkers for CSCs include cell surface antigens, intracellular transcription factors, and functional characteristics that vary across different cancer types. These biomarkers facilitate both experimental assessment and therapeutic targeting of CSCs.

Table 3: Established CSC Biomarkers Across Different Cancer Types

| Cancer Type | Key Biomarkers | Associated Functional Properties | Clinical Correlations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) | CD34⁺CD38⁻ [15] [8] | Chemoresistance, Dormancy | Poor prognosis, Relapse risk |

| Breast Cancer | CD44⁺CD24⁻/low, ALDH1⁺ [8] [19] | Metastasis, Therapy resistance | Shorter recurrence-free survival |

| Glioblastoma | CD133⁺, Nestin⁺, SOX2⁺ [15] [8] | Radioresistance, Invasion | Tumor aggressiveness |

| Colon Cancer | CD133⁺, CD44⁺, LGR5⁺ [8] [19] | Metastasis, Regeneration capacity | Recurrence risk |

| Pancreatic Cancer | CD133⁺, CD44⁺, CXCR4⁺ [8] | Stromal interaction, Drug resistance | Therapeutic resistance |

| Lung Cancer | CD133⁺, ALDH⁺ [8] | Plasticity, Adaptability | Advanced disease stage |

It is important to note that CSC biomarkers demonstrate significant plasticity, altering their expression in response to therapy, microenvironmental cues, and metabolic stress [19]. This dynamic regulation complicates both experimental assessment and therapeutic targeting, necessitating multiparameter approaches that account for CSC heterogeneity and adaptability.

Experimental Protocols for CSC Assessment

Tumor Sphere Formation Assay

The tumor sphere formation assay represents a fundamental functional test for CSC self-renewal and survival under non-adherent conditions. This protocol assesses the capacity of single cells to form clonal non-adherent spheres in serum-free conditions with defined growth factors [8].

Materials and Reagents:

- Ultra-low attachment plates

- Serum-free DMEM/F12 medium

- B27 supplement (50x)

- Recombinant human EGF (20 ng/mL)

- Recombinant human bFGF (10 ng/mL)

- Penicillin-Streptomycin solution

- Accutase enzyme solution for dissociation

Procedure:

- Dissociate tumor samples or cultured cells to single-cell suspension using Accutase

- Filter cells through 40μm strainer to remove aggregates

- Resuspend cells in serum-free sphere medium at 1,000-10,000 cells/mL

- Plate 100-200 μL per well in 96-well ultra-low attachment plates

- Culture for 7-14 days at 37°C with 5% CO₂

- Supplement with fresh growth factors every 3-4 days

- Quantify sphere number and diameter using inverted microscopy

- Passage spheres for serial sphere formation assays to assess self-renewal capacity

Interpretation and Analysis: Sphere-forming efficiency (SFE) is calculated as (number of spheres formed / number of cells seeded) × 100. Primary spheres can be dissociated and replated to assess self-renewal capacity through secondary and tertiary sphere formation. This assay provides a functional readout of CSC frequency and self-renewal potential under defined conditions.

Limiting Dilution Transplantation Assay

The limiting dilution transplantation assay represents the gold standard for quantifying tumor-initiating cell frequency through in vivo transplantation [15] [8]. This method provides the most rigorous assessment of CSC functional properties.

Materials and Reagents:

- Immunocompromised mice (NOD/SCID, NSG)

- Matrigel basement membrane matrix

- Cell sorting equipment (FACS) with appropriate antibodies

- Anesthetic reagents (isoflurane, ketamine/xylazine)

- Sterile surgical instruments for orthotopic transplantation

Procedure:

- Prepare single-cell suspensions from tumor specimens or cell lines

- Sort cells into defined subpopulations based on marker expression

- Serially dilute cells (e.g., 10⁵, 10⁴, 10³, 10², 10 cells) in PBS:Matrigel (1:1)

- Transplant cells orthotopically or subcutaneously into immunocompromised mice

- Monitor tumor formation weekly by palpation or imaging

- Continue observation for 12-24 weeks depending on cancer type

- Sacrifice animals at endpoint or when tumors reach 1.5cm diameter

- Analyze tumor histology to confirm recapitulation of original heterogeneity

Data Analysis: Tumor-initiating cell frequency is calculated using limiting dilution analysis software (e.g., ELDA) that applies Poisson statistics to determine the frequency of tumor-initiating cells in each population. Confidence intervals and statistical significance between different populations are determined using chi-square tests.

Emerging Therapeutic Approaches Targeting CSC Stemness

Strategic Approaches to CSC Eradication

The dual role of stemness in tumor initiation and maintenance presents corresponding dual opportunities for therapeutic intervention. Successful CSC-targeted therapies must address both the intrinsic properties of CSCs and their interactions with the tumor microenvironment.

Table 4: Therapeutic Strategies Targeting CSC Stemness Properties

| Therapeutic Strategy | Molecular Targets | Representative Agents | Development Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Signaling Pathway Inhibition | Wnt, Notch, Hedgehog | Vismodegib, Demcizumab | Clinical trials |

| Differentiation Therapy | Retinoic acid receptors | All-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) | Approved for AML |

| Metabolic Targeting | OXPHOS, Glycolysis, Autophagy | Metformin, Chloroquine | Preclinical/Clinical trials |

| Immunotherapy Approaches | CSC-specific antigens | CAR-T, Bispecific antibodies | Early clinical trials |

| Microenvironment Disruption | CXCR4, IL-6, TGF-β | Plerixafor, Siltuximab | Clinical evaluation |

| Epigenetic Modulation | EZH2, BMI1, DNMTs | GSK126, Azacitidine | Preclinical/Clinical development |

Innovative CSC-Targeting Platforms

Recent advances in therapeutic platforms have enabled more precise targeting of CSC populations. Engineering stem cells themselves to generate renewable cancer-fighting immune cells represents a particularly innovative approach [20]. In a first-in-human clinical trial, UCLA scientists successfully reprogrammed a patient's blood-forming stem cells to generate a continuous supply of functional T cells targeting the NY-ESO-1 cancer marker [20]. This approach creates an "internal factory" that produces tumor-targeting immune cells over time, potentially offering longer-lasting protection against recurrence [20].

Bispecific antibody-drug conjugates represent another emerging platform for CSC targeting. Iza-bren, a bispecific ADC targeting EGFR and HER3 mutations, has shown promise in early clinical trials for non-small cell lung cancer, with 75% of patients receiving the optimal dose showing tumor regression [21]. This dual-targeting approach may help address the heterogeneity and adaptability of CSC populations.

Diagram 2: Multidimensional Therapeutic Strategies for Targeting CSCs. Effective CSC eradication requires combined approaches targeting stemness pathways directly, disrupting supportive niches, and forcing differentiation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents for CSC Investigation

| Reagent Category | Specific Products | Research Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSC Surface Marker Antibodies | Anti-CD44, Anti-CD133, Anti-CD34, Anti-EPCAM, Anti-LGR5 | FACS isolation, Immunofluorescence, IHC | Species specificity, Clone validation, Multipanel compatibility |

| Stemness Transcription Factor Antibodies | Anti-OCT4, Anti-SOX2, Anti-NANOG, Anti-c-MYC | Intracellular staining, Western blot, ChIP | Fixation/permeabilization requirements, Nuclear localization |

| Pathway Modulators | Wnt agonists/antagonists, Notch inhibitors, Hh pathway blockers | Functional assays, Mechanism studies | Off-target effects, Dose optimization |

| Cell Culture Supplements | B27, N2, Recombinant EGF/FGF, KnockOut Serum Replacement | Tumor sphere assays, Clonal expansion | Batch-to-batch variability, Stability concerns |

| Proteomics Reagents | TMT/Isobaric tags, Phospho-enrichment materials, RPPA antibodies | Multi-omics profiling, Signaling analysis | Sample preparation rigor, Platform validation |

The dual role of stemness in tumor initiation and maintenance establishes CSCs as critical targets for oncogenic potential assessment and therapeutic development. Future research directions will need to address several key challenges, including the dynamic plasticity of CSC phenotypes, the lack of universal CSC biomarkers, and the complexities of CSC-microenvironment interactions [8]. Emerging technologies such as single-cell multi-omics, CRISPR-based functional screens, AI-driven analysis, and 3D organoid models are paving the way for more precise CSC characterization and targeting [8].

The clinical translation of CSC-targeting therapies will require careful assessment of therapeutic indices to avoid damaging normal tissue stem cells [22]. Additionally, the development of reliable biomarkers for monitoring CSC populations in patients during therapy remains an urgent need [16]. As our understanding of CSC biology deepens, integrative approaches combining metabolic reprogramming, immunomodulation, and targeted inhibition of core stemness pathways hold promise for overcoming therapy resistance and preventing tumor recurrence [8] [17]. The continued investigation of the dual role of stemness in cancer will undoubtedly yield crucial insights for both basic cancer biology and clinical oncology practice.

The study of mutation accumulation in stem cells is critical for understanding carcinogenesis and for assessing the oncogenic potential of stem cells intended for use in regenerative medicine. Somatic mutations acquired during a stem cell's lifetime can initiate tumorigenesis, making the rate and patterns of this accumulation a key area of research. This guide provides a direct comparison of mutation rates between developmental and adult stages of stem cells, synthesizing quantitative data, experimental methodologies, and molecular mechanisms to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

Quantitative Comparison of Mutation Rates

Data from genomic studies reveal distinct patterns of mutation accumulation in stem cells during developmental and adult life stages. The tables below summarize key quantitative findings.

Table 1: Comparison of Developmental and Adult Stem Cell Mutation Rates

| Life Stage | Stem Cell Type | Mutation Rate | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Developmental | Omnipotent stem cells (immediately after conception) | 2–3 mutations per division [23] | Pre-genome activation, limited DNA repair, diluted maternal factors [23] |

| Developmental | Stem cells (between conception and gastrulation) | ~1.6 mutations per division [23] | Rapid proliferation, chromatin remodeling, lenient DNA damage checkpoints [23] |

| Developmental | Hematopoietic Stem/Progenitor Cells (HSPCs) | 5.8-fold higher per year than postnatal rate [23] | Developmental processes and proliferation rate |

| Adult | Pluripotent Stem Cells (PSCs) in vitro | 3.5 ± 0.5 base substitutions per population doubling [24] | Culture conditions, particularly oxidative stress at 20% O₂ [24] |

| Adult | Intestinal & Liver Adult Stem Cells (ASCs) in vitro | 7.2 ± 1.1 and 8.3 ± 3.6 base substitutions per population doubling, respectively [24] | Culture conditions, oxidative stress [24] |

| Adult | Intestinal, Colon, & Liver ASCs in vivo | ~40 novel mutations per genome per year [25] | Endogenous mutational processes, tissue-specific cell division rates [25] |

Table 2: Impact of Culture Conditions on PSC Mutation Rates

| Culture Condition | Mutation Rate | Effect Compared to Standard Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Standard (20% O₂) | 0.28-0.37 x 10⁻⁹ SNVs per base-pair per day [26] | Baseline rate [26] |

| Low Oxygen (5% O₂) | 0.13 x 10⁻⁹ SNVs per base-pair per day [26] | >50% reduction in mutation rate [26] |

| Low Oxygen (3% O₂) | Not explicitly quantified | Lower mutational load, specifically in mutations linked to oxidative stress [24] |

| With ROCK Inhibitor (Y27632) | Not significantly different from standard [26] | No substantial impact on mutation rate [26] |

Experimental Protocols for Mutation Detection

Accurately measuring the low burden of somatic mutations in normal stem cells requires sophisticated, high-fidelity techniques.

Clonal Culture and Whole-Genome Sequencing

This method involves expanding a single stem cell into a clonal population to obtain sufficient DNA for whole-genome sequencing (WGS). Any mutation present in the original founding cell will be present in all descendant cells and thus show a high variant allele frequency (VAF) in the sequencing data. To measure mutations accumulated during a specific period, a subcloning step is performed after a defined culture period. Mutations found in the subclone, but not the original clone, represent those acquired during the intervening time [24] [23]. This approach effectively filters out germline variants and allows for the calculation of mutation rates per population doubling.

Duplex Sequencing (NanoSeq)

Duplex sequencing is an error-corrected bulk sequencing method that provides single-molecule sensitivity. The latest NanoSeq protocols use optimized fragmentation (sonication or enzymatic) and dideoxynucleotides during library preparation to prevent error transfer between DNA strands, achieving an ultralow error rate of below 5 errors per billion base pairs. This allows for the accurate detection of somatic mutations present in single cells within a polyclonal sample, without the need for clonal expansion. It is particularly powerful for profiling the driver mutation landscape across hundreds of clones from a single sample [27].

Signaling Pathways and Mutational Processes

The mutational processes active in stem cells leave distinct footprints in the genome, known as mutational signatures.

Oxidative Stress as a Key Driver in Vitro

A dominant mutational process in standard stem cell cultures is oxidative stress. Culturing pluripotent and adult stem cells under atmospheric oxygen (20% O₂) leads to a mutation spectrum dominated by C>A transversions, a signature linked to reactive oxygen species (ROS) [24]. This signature is significantly reduced when cells are cultured under physiological oxygen tension (3-5% O₂), demonstrating that oxidative stress is a major, modifiable contributor to in vitro mutation accumulation [26] [24].

Developmental vs. Adult Mutational Processes

The high mutation rate in early development is attributed to a unique biological context: cell division occurs before the full activation of the genome and the associated transcription-coupled repair machinery, and maternal DNA repair factors become diluted. Additionally, rapid proliferation, extensive chromatin remodeling, and more lenient cell-cycle checkpoints contribute to unavoidable mutation accumulation during this critical period [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Studying Stem Cell Mutations

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| Rho Kinase (ROCK) Inhibitor (Y27632) | Improves survival of human pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) after passaging, though it does not significantly alter the underlying mutation rate [26]. |

| Clinical Grade Human ES/iPS Cell Lines | Provides a standardized, physiologically relevant model for quantifying mutation rates in a therapeutic context [26] [28]. |

| Organoid Culture Systems | Enables the long-term, clonal expansion of primary adult stem cells (e.g., from intestine, liver) for mutation accumulation studies [24] [25]. |

| Duplex Sequencing (NanoSeq) Reagents | Ultra-low error rate sequencing is essential for detecting very low-frequency somatic mutations in polyclonal samples or single DNA molecules [27]. |

| Targeted Sequencing Panels | Focused gene panels allow for cost-effective, deep sequencing to profile driver mutation landscapes across hundreds of samples [27]. |

Stem cell mutation rates are not static, but are highly dependent on the biological context, with developmental stages exhibiting higher per-division rates than most adult tissues. A critical finding for regenerative medicine is that standard in vitro culture conditions can dramatically increase the mutational load in stem cells, primarily through oxidative stress. However, this risk is modifiable, as culturing under physiologically low oxygen tension significantly reduces mutation accumulation. These insights are paramount for developing safer stem cell-based therapies and for accurately assessing their oncogenic potential. Future research leveraging even more sensitive sequencing technologies will continue to refine our understanding of the complex interplay between mutation, selection, and cancer initiation in stem cell pools.

The stem cell niche is a dynamic microenvironment that plays a critical role in regulating stem cell behavior, maintenance, and transformation. Comprising various cellular components, signaling molecules, and physical factors, the niche provides essential cues that balance self-renewal and differentiation. Disruption of this delicate balance can drive malignant transformation, leading to cancer initiation and progression. This review systematically compares the oncogenic potential across different stem cell types by examining their unique niche interactions, supported by experimental data and signaling pathway analysis. Understanding these mechanisms provides crucial insights for developing targeted cancer therapies and assessing transformation risks in regenerative medicine applications.

The concept of the stem cell niche was first formally proposed by R. Schofield in 1978, hypothesizing that specialized microenvironments within tissues preserve stem cell proliferative potential and block maturation [29]. This niche hypothesis has since been validated across numerous mammalian tissues, with the niche functioning as a fundamental regulatory unit that governs stem cell fate decisions through direct cell-cell contact, secreted factors, and physical constraints [29] [30]. The niche maintains tissue homeostasis by precisely balancing stem cell activity—ensuring adequate self-renewal while producing differentiated progeny for tissue maintenance and repair.

When normal niche function is disrupted, the resulting dysregulation of stem cell behavior can initiate transformation processes. Cancer stem cells (CSCs), a subpopulation within tumors that exhibit stem-like properties, similarly depend on specialized "CSC niches" for their maintenance and protection [31]. These CSC niches share functional similarities with normal stem cell niches but promote tumorigenesis, immune evasion, and therapy resistance through aberrant signaling [32] [31]. This comparison guide examines how niche interactions influence transformation potential across stem cell types, providing experimental methodologies and analytical frameworks for oncogenic risk assessment.

Comparative Analysis of Stem Cell Niches and Transformation Risks

Table 1: Stem Cell Niche Characteristics and Transformation Potential Across Tissue Types

| Stem Cell Type | Key Niche Support Cells/Components | Critical Signaling Pathways | Transformation Risks/Cancer Associations | Experimental Model Systems |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hematopoietic Stem Cells (HSCs) | Osteoblasts, vascular cells, perivascular cells [29] | CXCL12, Wnt, Notch, ANG1 [29] | Acute Myeloid Leukemia (CD34+/CD38- phenotype) [32] [3] | Serial transplantation in immunodeficient mice [29] [8] |

| Intestinal Stem Cells | Paneth cells, vascular cells, fibroblasts [29] | Wnt, BMP, Notch [29] | Colorectal cancer (LGR5+ or CD133+ CBC cells) [29] [8] | Lineage tracing with Lgr5-CreERT2; intestinal organoids [29] |

| Neural Stem Cells | Vascular cells, ependymal cells, astrocytes [29] | Wnt, SHH, FGF, VEGF, Notch [29] | Glioblastoma (CD133+ or Nestin+ cells) [8] [3] | In vitro neurosphere assays; patient-derived organoids [8] |

| Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | Bone marrow stromal cells, adipocytes [33] | TGF-β, PDGFR-β/GPR91 [32] [33] | Sarcoma; niche-induced transformation via metabolic symbiosis [32] [7] | In vivo tracking with PET/MRI; immunocompromised mouse models [7] |

| Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) | Trophoblast cells, stromal fibroblasts [7] | LIF/STAT3, TGF-β/Activin [7] | Teratoma formation (testicular teratomas in 129-strain mice) [8] [3] | Teratoma assay in immunodeficient mice [7] |

Table 2: Quantitative Assessment of Stem Cell Transformation Potential

| Stem Cell Type | Transplantation Tumorigenicity Threshold | Time to Tumor Formation | CSC Frequency in Resulting Tumors | Key Transformation Markers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSCs (AML) | 1,000-10,000 CD34+/CD38- cells [3] | 8-12 weeks [3] | 0.2-1% in primary AML [3] | CD34+/CD38-, ALDH1 activity [32] [3] |

| Intestinal Stem Cells | As few as 200 LGR5+ cells [29] | 4-8 weeks [29] | 0.4-20% (varies by cancer stage) [8] [3] | LGR5, CD133, CD44 [29] [8] |

| Breast Stem Cells | 200 CD44+CD24-/low cells [3] | 12 weeks [3] | 3-4x higher in stage III vs. stage I [3] | CD44+/CD24-/low, ALDH1+ [32] [3] |

| Glioblastoma Stem Cells | 1,000-10,000 CD133+ cells [3] | 10-16 weeks [3] | 1-20% (depending on tumor subtype) [3] | CD133, Nestin, SOX2 [8] [3] |

| Melanoma Stem Cells | Varies significantly by model [8] | 6-20 weeks [8] | 0.4-82.5% (highly variable) [3] | CD133, CD166, ABC transporters [8] |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Niche-Driven Transformation

Lineage Tracing and Fate Mapping

Lineage tracing represents a fundamental methodology for identifying stem cell populations and characterizing their niche interactions in vivo [29]. The protocol utilizes genetic labeling to mark specific cell populations and track their progeny over time, enabling researchers to visualize differentiation hierarchies and identify cells with multilineage differentiation potential—a hallmark of stemness.

Detailed Protocol:

- Genetic Marker Selection: Choose a stem cell-specific promoter (e.g., Lgr5 for intestinal stem cells, Nestin for neural stem cells) to drive Cre recombinase expression [29]

- Reporter System: Cross with reporter mice containing a loxP-flanked STOP cassette preceding a fluorescent protein (e.g., tdTomato, GFP)

- Induction: Administer tamoxifen to activate CreERT2, inducing recombination and permanent label expression in target cells and their descendants

- Temporal Analysis: Track labeled cells at multiple timepoints (days to months) to assess self-renewal and differentiation capacity

- Tissue Processing: Analyze tissue sections via immunohistochemistry and fluorescence microscopy to quantify lineage contributions

This approach demonstrated that Lgr5+ crypt base columnar cells function as intestinal stem cells and can give rise to intestinal adenomas upon Apc deletion, identifying them as a cell-of-origin for colorectal cancer [29].

Serial Transplantation Assays

The gold standard for assessing functional stem cell activity, particularly for hematopoietic stem cells, involves serial transplantation into immunocompromised recipient animals [29] [8]. This method quantitatively measures self-renewal capacity—a critical property of both normal stem cells and CSCs.

Detailed Protocol:

- Cell Isolation: Purify candidate stem cell populations using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) with specific surface markers (e.g., CD34+CD38- for leukemia, CD44+CD24- for breast cancer)

- Primary Transplantation: Inject limiting dilutions of test cells into primary immunodeficient recipients (NOD/SCID or NSG mice)

- Engraftment Assessment: Monitor recipients for tumor development or tissue reconstitution over 8-24 weeks

- Secondary Transplantation: Isolate cells from primary recipients and transplant into secondary recipients to assess self-renewal capacity

- Quantitative Analysis: Calculate stem cell frequency using extreme limiting dilution analysis (ELDA) software

This methodology identified CD34+CD38- cells as acute myeloid leukemia stem cells, demonstrating their ability to recapitulate disease in recipient mice while more differentiated cells lacked this potential [8] [3].

Single-Cell Multi-Omics Analysis

Advanced sequencing technologies enable comprehensive characterization of stem cell heterogeneity and niche interactions at single-cell resolution, providing insights into transformation mechanisms [32] [8].

Detailed Protocol:

- Single-Cell Suspension: Dissociate tissue or tumor samples into single-cell suspensions while maintaining viability

- Cell Partitioning: Load cells into droplet-based systems (10X Genomics) for barcoding

- Library Preparation: Generate transcriptome (scRNA-seq), epigenome (scATAC-seq), or multimodal libraries

- Sequencing: Perform high-throughput sequencing on Illumina platforms

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Cluster cells based on expression profiles using Seurat or Scanpy

- Reconstruct differentiation trajectories with pseudotime algorithms (Monocle, PAGA)

- Identify cell-cell communication networks (NicheNet, CellChat)

- Correlate transcriptional states with niche localization through spatial transcriptomics

This approach has revealed the plastic nature of CSCs and their adaptive responses to microenvironmental cues, explaining how non-CSCs can reacquire stem-like properties under therapeutic pressure [8].

Signaling Pathways in Niche-Mediated Transformation

Niche-Activated Signaling Pathways in Stem Cell Transformation

The niche regulates stem cell behavior through complex signaling networks that, when dysregulated, drive oncogenic transformation. The diagram above illustrates key pathways implicated in this process, with the following mechanistic insights:

Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway: Niche-derived Wnt ligands maintain stemness in intestinal crypts and hematopoietic systems [29]. Dysregulation through APC mutations or β-catenin stabilization transforms LGR5+ intestinal stem cells, initiating colon carcinoma within days [29]. In hepatocellular carcinoma, β-catenin forms a positive feedback loop with PD-L1, simultaneously promoting immune evasion and stemness [31].

Notch Signaling: Mediates direct cell-cell communication between stem cells and niche cells [29]. In intestinal and neural niches, Notch activation inhibits differentiation, maintaining stem cell pools. In breast and pancreatic cancers, aberrant Notch activation expands CSC populations and drives therapy resistance [3].

Hedgehog Signaling: Regulates stem cell quiescence in multiple tissues [3]. In basal cell carcinoma and medulloblastoma, mutational activation of Hedgehog signaling drives tumor initiation from stem cells [3]. ADAR1-mediated RNA editing of GLI1 in hepatic CSCs enhances nuclear localization, promoting tumor initiation [32].

TGF-β/BMP Pathway: Exhibits context-dependent effects, often suppressing stemness in normal tissues but promoting epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and CSC phenotypes in advanced cancers [3]. In head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, TGF-β induces CD80 expression on CSCs, enabling immune evasion [31].

JAK/STAT Signaling: Regulates stem cell maintenance in Drosophila testes and mammalian epithelia [29]. Persistent STAT3 activation in CSCs promotes self-renewal and upregulates PD-L1 expression, contributing to immunosuppression [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Studying Niche-Driven Transformation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Transformation Assessment Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Surface Markers | CD34, CD38, CD44, CD24, CD133, LGR5, EpCAM | FACS isolation of stem cell populations | Identifies and purifies CSCs for functional assays [8] [3] |

| Signaling Pathway Inhibitors | DKK1 (Wnt inhibitor), DAPT (Notch inhibitor), Cyclopamine (Hedgehog inhibitor), SD-208 (TGF-β inhibitor) | Pathway perturbation studies | Tests functional dependency of CSCs on specific niche signals [3] |

| Cytokines/Growth Factors | CXCL12, EGF, FGF, TGF-β, BMP4, Wnt3a | In vitro niche reconstitution | Maintains stemness in culture and supports organoid formation [29] |

| Reporter Systems | Lgr5-GFP, Axin2-lacZ, PD-L1-GFP, TCF/LEF-GFP | Lineage tracing and signaling activity | Visualizes stem cell locations and pathway activation in real-time [29] |

| Immune Checkpoint Reagents | Anti-PD-1/PD-L1, anti-CTLA-4, anti-CD47, anti-CD24 | Immune evasion studies | Evaluates CSC ability to evade immune surveillance [31] |

| Metabolic Probes | 2-NBDG (glucose uptake), MitoTracker, C11-BODIPY581/591 (lipid peroxidation) | Metabolic profiling | Assesses metabolic adaptations in CSCs within hypoxic niches [32] [8] |

Discussion: Clinical Implications and Therapeutic Targeting

The comparative analysis reveals that transformation risk varies significantly across stem cell types, influenced by their respective niche interactions, turnover rates, and intrinsic regulatory mechanisms. Hematopoietic and intestinal stem cells demonstrate high susceptibility to niche-driven transformation, correlating with their high proliferative activity and well-defined hierarchical organizations [29] [8]. In contrast, mesenchymal stem cells exhibit lower inherent transformation risk but can promote tumor progression through paracrine signaling within established tumor microenvironments [7] [33].

Emerging therapeutic strategies aim to target niche interactions to eliminate CSCs while sparing normal stem cells. Approaches include:

- Niche Disruption: Targeting CSC-TME interactions through CXCR4 inhibitors to disrupt protective niches in leukemia [32]

- Immune Evasion Blockade: Combining PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors with CSC-specific vaccines to overcome immune privilege [32] [31]

- Metabolic Interdiction: Dual targeting of glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation to exploit CSC metabolic dependencies [8]

- Differentiation Therapy: Inducing CSC differentiation through BMP signaling to reduce therapy resistance [3]

Advanced model systems including 3D organoids, CRISPR-based functional screens, and AI-driven multiomics integration are accelerating the development of niche-targeted therapies [8]. Future research should focus on resolving niche heterogeneity at single-cell resolution across tumor types and developmental stages to identify context-specific vulnerabilities for therapeutic exploitation.

Assessment Arsenal: From Traditional Models to Cutting-Edge Screening Platforms

In the field of stem cell research and therapeutic development, assessing oncogenic potential represents a critical safety imperative. Tumorigenicity testing in immunocompromised mice serves as the gold-standard methodology for evaluating the risk of unwanted cell growth in living organisms, forming an essential component of the safety assessment for novel cell-based therapies [7]. These specialized animal models enable researchers to study the behavior of human-derived cells in an in vivo environment while circumventing the immune-mediated rejection that would normally eliminate foreign cells, thereby allowing for the detection of malignant transformation and uncontrolled proliferation [34].

The fundamental principle underlying these models involves implanting human stem cells or their differentiated derivatives into mice with compromised immune systems and monitoring for tumor formation over time. This approach provides invaluable preclinical data on the safety profile of cellular products, particularly for pluripotent stem cell-derived therapies where residual undifferentiated cells could pose significant tumorigenic risks [7]. As regenerative medicine continues to advance toward clinical applications, robust tumorigenicity assessment using these models has become indispensable for regulatory approval and patient safety, helping to identify and mitigate the risks of teratoma formation and malignant transformation before human trials commence [7].

Comparative Analysis of Immunocompromised Mouse Models

The evolution of immunocompromised mouse models has progressed significantly since the first nude mice were discovered in the 1960s, with each successive generation offering improved engraftment rates and broader applications for tumorigenicity testing [35] [34]. The selection of an appropriate model depends on multiple factors including the cell type being tested, required observation period, and specific research questions. The table below provides a comprehensive comparison of the most commonly utilized immunocompromised mouse strains in tumorigenicity assessment.

Table 1: Comparison of Immunocompromised Mouse Models for Tumorigenicity Testing

| Mouse Strain | Genetic Mutation(s) | Immune Deficiencies | Success Rate for PDX | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nude mice | Foxn1 | T-cell deficient | Low | Easy tumor monitoring; Cost-effective | Functional B cells and NK cells; Lower engraftment success |

| SCID mice | Prkdc | T-cell and B-cell deficient | Low | Better implantation than nude mice | NK cell activity; Radio-sensitive; Lymphocyte "leakage" |

| NOD-SCID mice | SCID (Prkdc) + NOD background | T-cells, B-cells, reduced NK cells, defective macrophages/dendritic cells | Moderate | Improved engraftment over SCID | Spontaneous lymphoma; Short lifespan; Radio-sensitive |

| NOG/NSG/NOJ mice | SCID + IL2Rγ null (Jak3) | T-cells, B-cells, NK cells, reduced macrophage/dendritic function | High | Outstanding engraftment success; Longer lifespan | Require strict SPF conditions; Higher cost |

| BRG/BRJ mice | IL2Rγ, Jak3, Rag-2 | T-cells, B-cells, NK cells, functional macrophages | High | Excellent engraftment; Radiation-resistant | Higher cost; Limited availability |

The progression from nude to more severely immunocompromised strains like NSG (NOD-scid gamma) mice has dramatically improved the success rates of patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models, which are crucial for accurate tumorigenicity assessment [34]. The NSG strain, with its deficiencies in T cells, B cells, and natural killer (NK) cells, along with defective macrophage and dendritic cell function, provides the most permissive environment for engrafting human cells, including those with lower tumorigenic potential [34]. This high level of immunodeficiency makes NSG mice particularly valuable for detecting minimal residual tumorigenic cells in stem cell populations, a critical consideration for clinical safety.

Experimental Design and Methodological Framework

Model Establishment and Cell Implantation

The construction of robust tumorigenicity models requires careful consideration of implantation methods and locations. Two primary approaches dominate the field: subcutaneous injection and orthotopic implantation. Subcutaneous injection involves depositing cells into the loose connective tissue beneath the skin, allowing for direct visual monitoring of tumor growth through simple caliper measurements [34]. This method offers technical simplicity and straightforward monitoring but may lack the appropriate tissue microenvironment that influences tumor development. Alternatively, orthotopic implantation places cells into the equivalent tissue of origin in the mouse (e.g., neural stem cells into brain tissue), potentially providing a more biologically relevant microenvironment but requiring more sophisticated monitoring techniques such as in vivo imaging [36].

The preparation of cells for implantation typically follows one of two strategies: single-cell suspensions or tissue fragment implantation. Single-cell suspensions, often prepared using enzymatic digestion, provide more controlled cell dosing and reduce sample heterogeneity, but may compromise cellular viability and intercellular interactions through the dissociation process [34]. Conversely, tissue fragment implantation better preserves native tissue architecture and cell-cell interactions, potentially maintaining crucial survival signals, though with less precise control over the number of cells implanted [34]. For tumorigenicity testing of stem cell populations, the use of basement membrane matrix (such as Matrigel) as a carrier has demonstrated improved engraftment efficiency by providing structural support and essential survival signals [34].

Monitoring and Endpoint Analysis

Comprehensive tumorigenicity assessment requires multimodal monitoring throughout the experimental timeline. The standard observation period typically extends from several weeks to months, with specific duration determined by the expected doubling time of the tested cells and their theoretical tumorigenic potential [7]. Regular tumor volume measurements using calipers (for subcutaneous models) or advanced imaging techniques (for orthotopic models) provide growth kinetics data. In vivo imaging technologies, including bioluminescent and fluorescent reporters, enable longitudinal tracking of cell survival and proliferation without sacrificing animals at intermediate timepoints [35].

Endpoint analyses encompass both gross pathological examination and detailed histological assessment. Histological staining of explanted tissues remains the definitive method for identifying tumor formation and characterizing tumor type [7]. Key techniques include hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining for general tissue architecture and identification of undifferentiated cells, immunohistochemistry for specific markers of pluripotency (OCT4, NANOG, SOX2) or differentiation, and special stains to identify tissue types representative of all three germ layers in the case of teratoma formation [7]. Additional molecular analyses may include PCR-based detection of human-specific genes to confirm human cell origin and quantify biodistribution beyond the implantation site [7].

Table 2: Key Analytical Methods in Tumorigenicity Assessment

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Primary Application | Key Output Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| In Vivo Monitoring | Caliper measurements, Bioluminescent imaging, PET/CT | Tumor growth tracking | Tumor volume, Growth kinetics, Cell survival |

| Histopathological Analysis | H&E staining, Immunohistochemistry, Special stains | Tumor identification and characterization | Tissue architecture, Pluripotency markers, Teratoma composition |

| Molecular Analysis | qPCR, Biodistribution studies, Genomic integration assays | Origin and distribution assessment | Human cell quantification, Off-target engraftment, Genetic stability |

| Functional Assessment | Secondary transplantation, Differentiation assays | Malignant potential evaluation | Self-renewal capacity, Differentiation potential |

Research Reagent Solutions for Tumorigenicity Testing

The successful implementation of tumorigenicity assays requires access to specialized reagents and resources. The following table outlines essential research tools and their applications in model development and analysis.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Tumorigenicity Testing

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Basement Membrane Matrix (Matrigel) | Provides extracellular matrix support for engrafted cells | Enhancing cell survival and engraftment efficiency after implantation [34] |

| Immunodeficient Mouse Strains | Host environment for human cell engraftment | NSG, NOG, NOD-SCID strains for tumorigenicity studies [34] |

| Cell Line Tracking Systems | Longitudinal monitoring of cell fate | Bioluminescent (luciferase) or fluorescent (GFP) reporters for in vivo imaging [35] |

| PDX Biobanks | Source of validated tumor models | NCI PDMR, EurOPDX Consortium, Jackson Laboratory PDX resources [34] |

| Human-Specific Detection Assays | Discrimination of human vs. mouse cells | qPCR for human-specific Alu sequences, human MHC immunohistochemistry [7] |

| Pluripotency Markers | Identification of undifferentiated stem cells | Antibodies against OCT4, NANOG, SOX2, SSEA-4 for immunohistochemistry [7] |

Experimental Workflow for Tumorigenicity Testing

The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow for conducting tumorigenicity testing in immunocompromised mice, from experimental design through data interpretation:

Integration with Complementary Preclinical Models

While immunocompromised mouse models represent the current gold standard for tumorigenicity testing, they are most informative when integrated with complementary preclinical approaches. Advanced in vitro systems such as 3D organoid cultures and organ-on-a-chip platforms provide valuable preliminary safety data with higher throughput capabilities [37]. These systems can model aspects of the tumor microenvironment and cell-cell interactions that influence tumorigenic potential, serving as important screening tools before progressing to more resource-intensive in vivo studies [37].

The emergence of proteomic-based stemness indices (PROTsi) and other computational approaches offers promising avenues for predicting tumorigenic risk based on molecular signatures [14]. These tools can quantify oncogenic dedifferentiation in relation to histopathological features and molecular profiles, potentially identifying high-risk cell populations before in vivo implantation [14]. Similarly, innovative imaging technologies such as immuno-PET with targeted tracers enable non-invasive monitoring of specific cell populations and their functional status in living animals, providing dynamic information about engrafted cell behavior [38].

Tumorigenicity testing in immunocompromised mice remains an indispensable component of the safety assessment pipeline for stem cell-based therapies. The strategic selection of appropriate mouse models, coupled with robust experimental design and comprehensive endpoint analyses, provides critical data on oncogenic risk that informs clinical translation decisions. As the field advances, the integration of these gold-standard in vivo models with emerging technologies in molecular imaging, multi-omics analysis, and complex in vitro systems will further enhance our ability to predict and mitigate tumorigenic potential in regenerative medicine applications.

Researchers must carefully match model selection to their specific research questions, considering the balance between engraftment efficiency, physiological relevance, and practical constraints. The continued refinement of these models and the development of standardized assessment protocols will strengthen the preclinical safety evaluation process, ultimately supporting the development of safer cell-based therapies for patients with unmet medical needs.

The assessment of oncogenic potential—the ability of cells to form tumors—is a critical step in stem cell research, safety profiling for cell therapies, and cancer biology. For decades, the soft agar colony formation assay has been the gold-standard in vitro method for detecting anchorage-independent growth, a hallmark of cellular transformation. However, the rise of more physiologically relevant three-dimensional (3D) models, particularly organoids, is revolutionizing the field. This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of these two pivotal techniques, framing them within the context of modern oncogenic risk assessment across different stem cell types. While the soft agar assay offers a straightforward, quantitative readout of transformation, 3D organoid cultures deliver unprecedented physiological relevance, recapitulating the complex architecture and cell-cell interactions of in vivo tissues [39] [40]. Understanding the strengths, limitations, and appropriate applications of each method is essential for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to accurately evaluate the tumorigenic risk of novel stem cell-based therapies or to model cancer initiation and progression.

Fundamental Technique Comparison

The following table summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and limitations of the soft agar and 3D organoid methods.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Soft Agar and 3D Organoid Assays

| Feature | Soft Agar Colony Formation Assay | 3D Organoid Cultures |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Measures anchorage-independent growth in a semi-solid medium [41]. | Stem cells self-organize into 3D structures mimicking organ architecture [39] [42]. |

| Key Readout | Number and/or size of colonies formed after 2-4 weeks [41]. | Organoid morphology, growth, viability, and differentiation over long-term culture [39] [40]. |

| Throughput | High; suitable for drug screening and large-scale experiments [41]. | Variable; can be medium to high with specialized platforms, but often lower than soft agar [40] [43]. |

| Physiological Relevance | Low; lacks tissue context, ECM, and complex cell interactions [40]. | High; recapitulates cell-ECM interactions, nutrient gradients, and in vivo-like architecture [39] [40]. |

| Key Applications | - Identifying transformed cells- Oncogene validation- Drug cytotoxicity screening [41] | - Disease modeling (including cancer)- Drug screening & personalized medicine- Host-microbe interaction studies [39] [44] |

| Primary Limitations | - Does not model tissue-specific contexts- Can yield false positives/negatives- Opaque matrix complicates imaging [41] | - Technically challenging & costly- Batch-to-batch variability (e.g., Matrigel)- Limited scalability & standardization [40] [43] |

Application in Oncogenic Potential Assessment

When specifically applied to evaluating the oncogenic risk of different stem cell types, the two assays provide complementary insights. The choice of model depends heavily on the research question, balancing throughput with biological complexity.

Table 2: Assessing Oncogenic Potential Across Stem Cell Types

| Stem Cell Type | Oncogenic Risk & Context | Soft Agar Assay Utility | 3D Organoid Model Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) | High risk due to reprogramming factors and culture-induced mutations; critical for safety of regenerative therapies [7]. | Excellent for initial, high-throughput screening of transformation events in undifferentiated or differentiated iPSCs. | Models multi-stage transformation within a tissue context; can co-culture with stromal cells to assess microenvironmental impact [39]. |

| Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cells (MSCs) | Lower but present risk; potential for transformation after long-term culture; used in numerous clinical trials [7] [45]. | Standardized method for quality control during biomanufacturing to ensure safety prior to clinical application. | Patient-derived tumor organoids can be used to study MSC-tumor interactions and assess pro- or anti-tumorigenic effects of MSC therapies [8]. |