Optimizing Neuronal Maturation from iPSCs: Strategies for Robust Models in Research and Drug Development

The efficient generation of mature, functional neurons from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) is critical for advancing disease modeling and drug screening.

Optimizing Neuronal Maturation from iPSCs: Strategies for Robust Models in Research and Drug Development

Abstract

The efficient generation of mature, functional neurons from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) is critical for advancing disease modeling and drug screening. This article synthesizes the latest research to provide a comprehensive guide on neuronal maturation. We first explore the foundational biology, including the essential metabolic remodeling and key transcriptional changes that define neuronal maturation. We then compare core differentiation methodologies, such as direct NGN2 programming and SMAD inhibition, detailing their specific applications. A dedicated section addresses common challenges like heterogeneity and immaturity, offering proven optimization strategies to enhance reproducibility and functional output. Finally, we outline rigorous validation frameworks, emphasizing the importance of multi-omics profiling and functional electrophysiology for benchmarking neuronal maturity. This resource is tailored for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to establish robust, high-fidelity neuronal models.

The Blueprint of Maturation: Metabolic and Molecular Hallmarks of Neuronal Development

The maturation of neurons derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) involves a critical metabolic transition from glycolytic metabolism to oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS). This reprogramming is essential for neurons to meet their high energy demands and acquire adult-like function. iPSCs and neural progenitor cells (NPCs) primarily utilize aerobic glycolysis, similar to cancer cells in the Warburg effect, to generate energy and biosynthetic precursors. However, as neurons differentiate and mature, they undergo a fundamental metabolic shift toward mitochondrial OXPHOS, which supports more efficient adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production, mitochondrial biogenesis, and the maintenance of redox homeostasis [1] [2].

This metabolic transition is not merely a passive consequence of differentiation but an actively regulated process essential for neuronal survival and function. Disruptions in this metabolic shift can lead to impaired neuronal maturation, dysfunction, and even cell death, highlighting its critical role in neurodevelopment and the modeling of neurological diseases [2]. Understanding and controlling this metabolic reprogramming is therefore crucial for optimizing neuronal maturation from iPSCs for research and therapeutic applications.

Key Metabolic Changes During the Transition

The shift from glycolysis to OXPHOS during neuronal maturation is marked by distinct molecular and metabolic events. The table below summarizes the core changes in key metabolic enzymes and regulators.

Table 1: Key Metabolic Parameters in the Glycolysis to OXPHOS Transition

| Metabolic Parameter | Status in NPCs / Glycolytic Phase | Status in Mature Neurons / OXPHOS Phase | Functional Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hexokinase 2 (HK2) | High expression [2] | Loss of expression [2] | Reduces glycolytic flux; essential for neuronal survival |

| Lactate Dehydrogenase A (LDHA) | High expression [2] | Loss of expression [2] | Shunts pyruvate away from lactate production |

| Pyruvate Kinase Splicing (PKM) | Predominantly PKM2 isoform [2] | Shift to PKM1 isoform [2] | Alters glycolytic rate and metabolic intermediate availability |

| c-MYC / N-MYC | High protein levels [2] | Dramatic decrease [2] | Derepresses transcription of HK2 and LDHA |

| PGC-1α / ERRγ | Lower expression [2] | Significant increase [2] | Sustains transcription of OXPHOS and mitochondrial genes |

| Mitochondrial Mass | Lower relative mass [3] | Increases proportionally with neuronal growth [2] | Enhances capacity for oxidative metabolism |

| NAD+/NADH Ratio | Lower (e.g., ~0.53 in young iNs) [3] | Higher (indicative of oxidative metabolism) [3] | Reflects the redox state and metabolic capacity of the cell |

This metabolic switch ensures that neurons can generate sufficient ATP through efficient OXPHOS to support their high energy requirements for functions like action potential firing and synaptic transmission. The upregulation of mitochondrial and antioxidant pathways, along with an increase in enzyme-bound NAD(P)H, is consistent with this shift toward oxidative metabolism [1].

Experimental Protocols for Monitoring Metabolic Reprogramming

Protocol: Multi-Phenotypic Imaging Assay for Neuronal Maturity

This protocol uses high-content imaging to simultaneously track morphological and functional maturation readouts, which are intrinsically linked to the metabolic state of the neurons [4].

Key Materials:

- Cells: hPSC-derived cortical neurons (e.g., NGN2-induced).

- Culture Vessels: 96-well plates suitable for high-content imaging.

- Key Reagents:

- Primary antibodies: anti-MAP2 (for dendrites), anti-FOS, anti-EGR-1 (for Immediate Early Genes).

- Secondary antibodies with suitable fluorophores.

- DAPI (for nuclear staining).

- 75mM KCl solution (for depolarization).

- Cell fixation and permeabilization reagents.

Methodology:

- Cell Culture and Differentiation: Plate and differentiate hPSC-derived cortical neurons according to established protocols.

- Compound Treatment (Optional): If testing maturation accelerants, apply compounds between days 7-14 of differentiation.

- Compound Withdrawal: Culture cells in compound-free medium for an additional 7 days (e.g., days 14-21) to identify long-lasting maturation effects.

- Stimulation and Fixation: On the day of analysis, stimulate one set of wells with 75mM KCl for 2 hours to induce neuronal activity. Keep a parallel set of wells under basal conditions. After stimulation, immediately fix the cells.

- Immunostaining: Perform immunostaining for MAP2 (neurite outgrowth), FOS, and EGR-1 (neuronal activity), with DAPI counterstain (nuclear morphology).

- High-Content Imaging and Analysis: Acquire images using a high-content microscope and analyze the following parameters with appropriate software:

- Neurite Outgrowth: Automated tracing of MAP2-positive structures to quantify total neurite length and branching.

- Nuclear Morphology: DAPI staining to measure nuclear size and roundness.

- Functional Activity: Calculate the fraction of neurons positive for FOS and EGR-1 in KCl-stimulated wells after subtracting the baseline signal from unstimulated wells.

Protocol: Functional Metabolic Analysis with Seahorse XF Analyzer

This protocol directly measures the metabolic flux of live neurons, quantifying glycolytic rate and mitochondrial respiration in real-time [3].

Key Materials:

- Cells: Mature iPSC-derived neurons or iNs.

- Instrument: Seahorse XF Analyzer (Agilent).

- Key Kits and Reagents:

- Seahorse XF Glycolysis Stress Test Kit (contains glucose, oligomycin, 2-DG).

- Seahorse XF Cell Mito Stress Test Kit (contains oligomycin, FCCP, rotenone/antimycin A).

- Seahorse XF Base Medium (assay-specific, without bicarbonate).

- Coating matrix (e.g., poly-l-ornithine/laminin) for assay plates.

Methodology for Glycolysis Stress Test:

- Cell Preparation: Seed neurons in a Seahorse XF assay plate and allow them to mature for the desired time. On the day of the assay, cells should be at an appropriate density (e.g., 50,000-100,000 cells per well).

- Medium Exchange: One hour before the assay, replace the culture medium with Seahorse XF Base Medium (pH 7.4) supplemented with 2mM L-glutamine. Incubate cells in a non-CO₂ incubator at 37°C.

- Assay Run: Load the compound ports and run the assay in the Seahorse XF Analyzer. The standard injection sequence is:

- Port A: Glucose (final conc. 10mM) → Measures basal glycolysis.

- Port B: Oligomycin (ATP synthase inhibitor, final conc. 1µM) → Measures glycolytic capacity.

- Port C: 2-Deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG, hexokinase inhibitor, final conc. 50mM) → Confirms glycolytic dependency.

- Data Analysis: Calculate key parameters from the Extracellular Acidification Rate (ECAR) profile: Glycolysis (rate after glucose), Glycolytic Capacity (rate after oligomycin), and Glycolytic Reserve.

Methodology for Mito Stress Test:

- Cell Preparation: Follow the same steps as for the Glycolysis Stress Test.

- Assay Run: The standard injection sequence is:

- Port A: Oligomycin (final conc. 1µM) → Inhibits ATP synthase, revealing ATP-linked respiration.

- Port B: FCCP (mitochondrial uncoupler, final conc. 0.5-2µM, must be optimized) → Measures maximal respiratory capacity.

- Port C: Rotenone & Antimycin A (Complex I and III inhibitors, final conc. 0.5µM each) → Shuts down mitochondrial respiration, revealing non-mitochondrial oxygen consumption.

- Data Analysis: Calculate key parameters from the Oxygen Consumption Rate (OCR) profile: Basal Respiration, ATP-linked Respiration, Maximal Respiration, and Spare Respiratory Capacity.

Visualization of Metabolic Pathways and Regulatory Logic

Diagram 1: Logic of Metabolic Reprogramming During Neuronal Maturation. The transition from NPCs to mature neurons is driven by a transcriptional switch where MYC proteins decline and PGC-1α/ERRγ increase, leading to a shut-down of aerobic glycolysis and activation of OXPHOS [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Studying Metabolic Reprogramming in Neuronal Maturation

| Reagent / Tool | Category | Primary Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| NGN2-iPSC Line | Cell Model | Enables rapid, synchronous differentiation of iPSCs into excitatory cortical neurons [1]. | Base model for studying metabolic transitions during neurogenesis. |

| GSK2879552 | Small Molecule Inhibitor | Inhibits Lysine-Specific Demethylase 1 (LSD1/KDM1A), an epigenetic regulator [4]. | Part of maturation cocktails (e.g., GENtoniK) to accelerate neuronal maturity. |

| EPZ-5676 (Pevonedistat) | Small Molecule Inhibitor | Inhibits Disruptor of Telomerase-like 1 (DOT1L), a histone methyltransferase [4]. | Part of maturation cocktails to promote epigenetic remodeling for maturation. |

| NMDA & Bay K 8644 | Receptor Agonists | Activate NMDA receptors and L-Type Calcium Channels (LTCC), respectively, to induce calcium-dependent transcription [4]. | Part of maturation cocktails to trigger activity-dependent maturation pathways. |

| Seahorse XF Glycolysis Stress Test Kit | Metabolic Assay Kit | Measures glycolytic function in live cells by quantifying extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) [3]. | Functional profiling of glycolytic flux in NPCs vs. neurons. |

| Seahorse XF Mito Stress Test Kit | Metabolic Assay Kit | Measures mitochondrial respiratory function in live cells by quantifying oxygen consumption rate (OCR) [3]. | Functional profiling of OXPHOS capacity in maturing neurons. |

| Anti-HK2 / Anti-LDHA Antibodies | Biochemical Reagent | Detect protein levels of key glycolytic enzymes via Western Blot or Immunostaining [2]. | Tracking the downregulation of the glycolytic program. |

| Anti-PGC-1α Antibody | Biochemical Reagent | Detects protein levels of a master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis [2]. | Confirming the upregulation of the oxidative program. |

| ¹³C₆-Glucose | Metabolic Tracer | Allows for metabolic flux analysis (MFA) to track glucose utilization through various pathways [1]. | Mapping precise metabolic routes (e.g., glycolysis, PPP, TCA) during differentiation. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: My iPSC-derived neurons are maturing too slowly, failing to achieve robust electrophysiological activity even after 50+ days in culture. What strategies can accelerate this process?

Answer: Slow maturation is a common challenge due to the intrinsically slow human developmental clock. A proven strategy is to use a combination of small molecules that target epigenetic and activity-dependent pathways.

- Recommended Solution: Treat neurons between days 7-14 of differentiation with a cocktail such as "GENtoniK," which includes:

- GSK2879552 (LSD1 Inhibitor): Promotes epigenetic remodeling.

- EPZ-5676 (DOT1L Inhibitor): Alters histone methylation.

- NMDA & Bay K 8644: Activates NMDA receptors and L-type calcium channels to stimulate calcium-dependent transcription.

- Protocol: After treatment, culture the neurons in compound-free medium for an additional 7 days. This triggers a long-lasting "memory" of maturation, leading to significant improvements in synaptic density, neurite outgrowth, and electrophysiological function [4].

FAQ 2: How can I conclusively demonstrate that the metabolic shift from glycolysis to OXPHOS has occurred in my neuronal cultures?

Answer: A multi-modal approach is required to confirm this metabolic transition conclusively.

- Molecular Level: Use Western Blot or RNA analysis to show the downregulation of glycolytic enzymes (HK2, LDHA) and a splicing shift in pyruvate kinase from PKM2 to PKM1.

- Functional Level: Employ the Seahorse XF Analyzer to directly measure metabolic fluxes. You should observe a high Extracellular Acidification Rate (ECAR, indicating glycolysis) in NPCs/precursors, which decreases as the Oxygen Consumption Rate (OCR, indicating OXPHOS) increases in mature neurons [3] [2].

- Metabolic Flux Analysis: Use ¹³C₆-Glucose tracing to track the fate of glucose carbons. In mature neurons, you should see enhanced labeling of TCA cycle intermediates and a shift in glucose utilization toward biosynthetic and antioxidant pathways like the pentose phosphate pathway [1].

FAQ 3: I am observing high cell death during the metabolic transition phase. What could be the cause, and how can I prevent it?

Answer: Failure to properly downregulate the glycolytic program is a potential cause of cell death during neuronal maturation.

- Root Cause: Constitutive expression of glycolytic enzymes HK2 and LDHA during differentiation has been shown to induce neuronal cell death. The shut-off of aerobic glycolysis is essential for neuronal survival [2].

- Prevention Strategy:

- Monitor Expression: Check that your differentiation protocol effectively reduces the protein levels of HK2 and LDHA over time.

- Avoid Over-feeding: Do not use media with excessively high glucose concentrations (e.g., >17.5 mM) during later stages of maturation, as this can force sustained glycolysis. Switching to neuronal media with lower glucose (e.g., 2.5-5 mM) may be beneficial [1].

- Support Mitochondrial Health: Ensure mitochondrial function is not compromised. Assess mitochondrial membrane potential and reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels. Supplementing culture media with antioxidants (e.g., uridine, catalase) can help manage oxidative stress associated with increased OXPHOS [3].

FAQ 4: My neuronal cultures show inconsistent metabolic profiles. How can I account for metabolic heterogeneity?

Answer: Metabolic heterogeneity can arise from mixed cell populations or intrinsic variability.

- Characterization: First, use neuronal markers (e.g., MAP2) to confirm the purity and homogeneity of your culture. Contamination with proliferative NPCs or non-neuronal cells, which have different metabolic profiles, can skew results [4].

- Single-Cell Analysis: Consider techniques like single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) to profile metabolic gene expression across the entire population and identify distinct subpopulations [1].

- Functional Heterogeneity: Use the Seahorse Mito Stress Test to calculate the spare respiratory capacity. A low and variable spare capacity can indicate a population with limited metabolic flexibility and high vulnerability to stress, which may be a sign of immaturity or underlying dysfunction [3].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the key transcriptional differences between the two main neuronal differentiation protocols?

The choice between differentiation through neural stem cells (NSCs) via DUAL SMAD inhibition and direct differentiation via NGN2 overexpression significantly impacts the transcriptional profile and cellular composition of the resulting neural cultures [5].

Table: Transcriptional and Cellular Profiles of Differentiation Methods

| Differentiation Method | Key Transcriptional Features | Resulting Cellular Population | Time Requirement |

|---|---|---|---|

| DUAL SMAD Inhibition | Enriched in neural stem cell (NSC) and glial markers [5] | Heterogeneous mix of neurons, neural precursors, and glial cells [5] | Time-consuming, several weeks [5] |

| NGN2 Overexpression | Elevated markers for cholinergic and peripheral sensory neurons; reduced glial markers [5] | Homogeneous culture composed predominantly of mature neurons [5] | Rapid, single-step induction [5] |

FAQ 2: What are the critical functional milestones during neuronal maturation, and when do they typically occur?

A comprehensive study tracking neurons over 10 weeks identified a consistent sequence of functional maturation events, providing a robust temporal framework for experiments [6].

Table: Functional Maturation Timeline of Human iPSC-Derived Neurons

| Weeks In Vitro | Key Maturation Milestones |

|---|---|

| Up to Week 5 | Neurons exhibit high membrane resistance and developing excitability. Firing profiles evolve towards maturity [6]. |

| Week 5 | Firing profiles become consistent with those of mature, regular-firing neurons [6]. |

| Week 6 Onwards | Abundant fast glutamatergic and depolarizing GABAergic synaptic connections emerge. Synchronized network activity is observed [6]. |

FAQ 3: Beyond transcriptomics, what proteomic and phosphoproteomic changes occur during maturation?

Proteomic and phosphoproteomic analyses provide a crucial layer of information that is often discordant with transcriptomic data, revealing distinct functional pathways activated during neuronal differentiation [7].

Table Key Proteomic and Phosphoproteomic Signatures During Neuronal Maturation

| Analysis Type | Key Dynamic Pathways and Signatures |

|---|---|

| Proteomics | Distinct changes in mitochondrial pathways and functions over the differentiation time course [7]. |

| Phosphoproteomics | Specific regulatory dynamics in GTPase signaling pathways and microtubule proteins. Phosphosites related to axon functions and RNA transport show changes independent of protein expression levels [7]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Heterogeneity and Immature Neuronal Cultures Issue: The resulting neuronal cultures are too heterogeneous, contain unwanted cell types like glia, or exhibit immature electrophysiological properties after several weeks. Solution:

- Protocol Selection: Consider using the direct NGN2 overexpression method if a homogeneous, highly neuronal population is required for your application (e.g., disease modeling of specific neuronal subtypes) [5] [8].

- Functional Validation: Do not rely solely on transcriptomic data or the expression of early neuronal markers like Tuj1. Implement functional assays, such as patch-clamp electrophysiology, to confirm the development of mature action potentials and synaptic activity, which typically stabilize around week 5 [6].

- Monitor Network Activity: Use calcium imaging to track the emergence of synchronized network activity, a key indicator of functional maturation that typically appears from the sixth week [6].

Problem: Inconsistent Maturation Across Cell Lines or Batches Issue: Neuronal maturation timelines or efficiency vary significantly between different iPSC lines or different differentiation batches. Solution:

- Standardize Progenitors: Incorporate an intermediate step where neuronal progenitors are generated and banked. This allows for the use of a consistent, homogenous starting population for terminal differentiation, improving reproducibility [8].

- Multi-Omics Quality Control: Establish a set of baseline quality control checks. This can include tracking the progressive increase in GABAergic or other neuronal subtype markers via transcriptomics [9] and monitoring specific proteomic signatures, such as mitochondrial protein dynamics [7].

- Monitor Metabolic Shifts: Assess mitochondrial function, as maturation is accompanied by specific metabolic changes. Aged or impaired neurons often show decreased ATP levels, mitochondrial membrane potential, and respiration [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for iPSC-Derived Neuronal Maturation Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Neuronal Maturation | Examples / Key Components |

|---|---|---|

| Small Molecule Inhibitors | Directs neural induction by patterning cell fate. | DUAL SMAD inhibitors (SB431542, LDN-193189) [5] |

| Inducible Transcription Factors | Drives rapid, synchronous neuronal differentiation. | Doxycycline-inducible NGN2 systems [5] [8] |

| Specialized Neuronal Media | Supports long-term survival, health, and synaptic activity of mature neurons. | BrainPhys medium, supplemented with BDNF, GDNF, cAMP, and ascorbic acid [6] |

| Trophic Factors & Signaling Molecules | Enhances neuronal survival, outgrowth, and synaptic maturation. | BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor), GDNF (glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor) [6] |

| Cell Culture Substrates | Provides an adhesive, biologically relevant matrix for neurite outgrowth. | Poly-L-Ornithine (PLO), Laminin, Poly-D-Lysine (PDL) [6] |

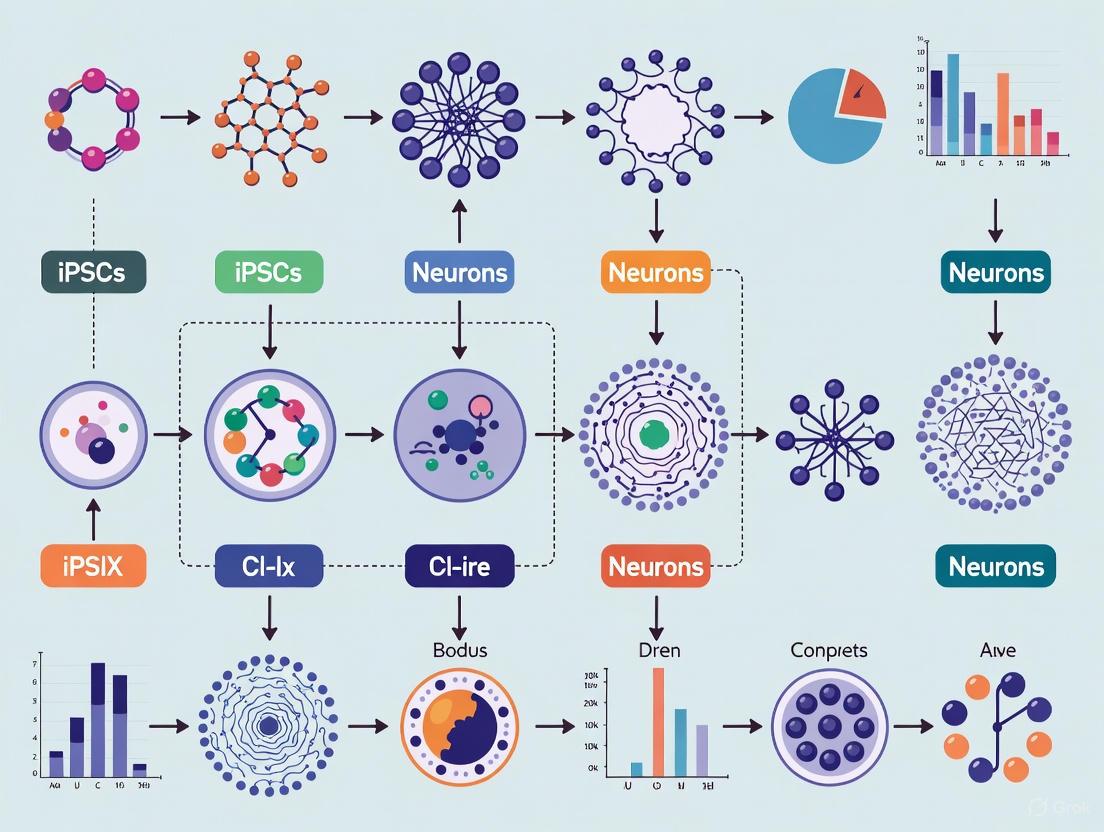

Experimental Workflow & Data Integration

The following diagram outlines a comprehensive workflow for differentiating iPSCs into mature neurons and validating their maturation status using multi-omics and functional approaches.

Signaling Pathways in Neuronal Maturation

The maturation process is regulated by intricate signaling pathways that are reflected in both transcriptional and proteomic data. The following diagram summarizes key pathways and their functional outcomes.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the most critical period for metabolic remodeling during neuronal differentiation, and how can I confirm it in my cultures?

The first week of differentiation is a critical window for metabolic specialization in human iPSCs differentiating into cortical neurons [10]. During this period, cells undergo a essential metabolic shift from glycolysis towards oxidative phosphorylation. You can confirm this transition in your cultures using Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy (FLIM) to detect a progressive increase in enzyme-bound NAD(P)H, which is a hallmark of a shift toward oxidative metabolism [10]. Additionally, 13C₆-glucose metabolic flux analysis can reveal enhanced labeling of pentose phosphate pathway intermediates and glutathione, indicating a shift toward biosynthetic and antioxidant glucose utilization [10].

Q2: My iPSC-derived neurons show inconsistent maturation after 4 weeks. What functional benchmarks should I use to track their development?

A multifaceted assessment strategy is essential. The table below outlines key functional parameters that evolve during neuronal maturation, based on a comprehensive 10-week study [6].

Table: Functional Maturation Benchmarks for Human iPSC-Derived Neurons

| Maturation Week | Membrane Resistance | Firing Profile | Synaptic Activity | Network Activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-4 | High | Immature, inconsistent | Limited | None |

| 5 | Decreasing | Mature, regular firing pattern emerges | Developing | None |

| 6-7 | Lower | Consistent regular firing | Abundant fast glutamatergic and depolarizing GABAergic | Synchronized network bursts appear |

| 8-10 | Adult-like | Stable, mature | Mature, balanced inhibition/excitation | Robust, synchronized |

Q3: Does 3D culture improve the maturation of neural progenitor cells (NPCs), and when should I transition to this system?

Yes, transitioning NPCs to 3D floating neurosphere cultures significantly improves homogeneity and differentiation potential [11]. This method promotes a more homogenous expression of the NPC marker PAX6 and increases the subsequent differentiation potential toward astrocytes, as evidenced by higher expression of markers like GFAP and aquaporin 4 (AQP4) [11]. You should implement this system during the NPC expansion phase, after initial neural induction but before terminal differentiation [11] [12].

Q4: I am working with cardiomyocyte differentiation. What combined stimuli most effectively define a maturation window for electrophysiological maturity?

For iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes (iPSC-CMs), a combination of metabolic, structural, and electrical stimuli applied during the post-differentiation phase drives advanced maturity. A 2025 study systematically tested these factors and found that electrostimulation (ES) was the key driver for mitochondrial development and metabolic maturation [13]. When combined with a lipid-enriched maturation medium (MM) with high calcium and nanopatterning (NP) for cell alignment, the protocol generated cardiomyocytes with adult-like electrophysiological properties, including a more negative resting membrane potential and a faster action potential upstroke [13].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Tracking Metabolic Maturation in Cortical Neurons

This protocol defines the critical window for metabolic remodeling during the first two weeks of neuronal differentiation [10].

- Key Materials: Human iPSCs with inducible NGN2, neural differentiation media, doxycycline.

- Week 0-1 (Critical Window): Initiate differentiation with doxycycline to induce NGN2 overexpression. Analyze cells at day 7.

- Day 7 Analysis: Perform high-resolution respirometry to detect early enhancements in oxidative phosphorylation. Use FLIM to measure the ratio of enzyme-bound to free NAD(P)H, indicating a shift toward oxidative metabolism [10].

- Week 1-2 (Progression): Continue differentiation and analyze cells at day 14.

- Day 14 Analysis: Conduct 13C₆-glucose metabolic flux analysis. Expect to see delayed labeling of TCA cycle metabolites but enhanced labeling of pentose phosphate pathway intermediates and glutathione, confirming a metabolic shift to support biosynthesis and antioxidant defense [10].

- Troubleshooting: If metabolic shift is not observed, ensure the purity of your neuronal population by checking NGN2 induction efficiency and the health of the starting iPSC culture.

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow and the key metabolic shifts to monitor during this critical period.

Protocol 2: A Multifactorial 10-Week Maturation Timeline for Neurons

This protocol provides a week-by-week framework for functional maturation, allowing you to plan experiments based on defined neuronal capabilities [6].

- Key Materials: Human NPCs, Poly-L-Ornithine/Laminin coated plates, BrainPhys Neuronal Medium, BDNF, GDNF, dibutyryl cyclic-AMP, ascorbic acid [6].

- Weeks 1-4 (Baseline Excitability): Plate NPCs and initiate terminal differentiation. During this phase, neurons will exhibit high membrane resistance and developing, inconsistent firing profiles. Focus on immunocytochemistry for morphological markers (e.g., MAP2, TAU) and initial patch-clamp recordings to confirm the presence of action potentials [6].

- Weeks 5-6 (Functional Synapse Formation): This is a critical window for the emergence of mature electrophysiological properties.

- Week 5: Perform patch-clamp to identify the emergence of a mature, regular firing pattern. Membrane resistance will noticeably decrease [6].

- Week 6: Test for the appearance of fast glutamatergic synaptic currents and depolarizing GABAergic responses. Calcium imaging can now be used to detect the first synchronized network bursts [6].

- Weeks 7-10 (Network Stabilization): The culture develops into a stable, interconnected network.

- Focus: Continue monitoring synaptic and network activity. The alterations in GABAA receptor subunit expression occur during this period, leading to more mature inhibitory signaling. Use Sholl analysis on biocytin-filled neurons to quantify complex morphological development [6].

- Troubleshooting: If synchronized network activity fails to develop by week 7, ensure a sufficient density of neurons and consistent, twice-weekly half-medium changes with fresh BDNF/GDNF.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Maturation Studies

Table: Key Reagents for Defining Maturation Windows

| Reagent/Condition | Function in Maturation | Key Readouts |

|---|---|---|

| NGN2 Inducible System [10] | Drives rapid, synchronous differentiation of iPSCs to excitatory cortical neurons. | Neuronal purity, expression of cortical markers. |

| BDNF & GDNF [6] | Neurotrophins that support neuronal survival, neurite outgrowth, and synaptic plasticity during long-term maturation. | Increased neurite complexity, emergence of synaptic activity. |

| 3D Neurosphere Culture [11] [12] | Provides a more in vivo-like environment, enhancing NPC homogeneity and astrocyte differentiation potential. | Increased PAX6 homogeneity, higher GFAP expression post-differentiation. |

| Metabolic Maturation Media [14] | Shifts energy metabolism from glycolysis to fatty acid oxidation; critical for cardiomyocyte maturation. | TTX-sensitive action potentials, increased mitochondrial content & respiration. |

| Electrostimulation (ES) [13] | Key driver for mitochondrial development and electrophysiological maturation in cardiomyocytes. | More negative resting membrane potential, faster action potential upstroke, "notch-and-dome" morphology. |

| Nanopatterning (NP) [13] | Provides structural cues that promote sarcomere organization and cell alignment in cardiomyocytes. | Organized sarcomeres, elongated nuclei, improved connexin 43 localization. |

The following diagram summarizes how these different stimuli can be integrated in a combined maturation strategy for specific cell types.

Protocols in Practice: A Guide to Differentiation Methods and Their Target Applications

Transcription factor programming of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) using Neurogenin-2 (NGN2) has emerged as a powerful method for generating human excitatory neurons. This approach significantly reduces heterogeneity and improves consistency across different stem cell lines compared to extrinsic factor-based differentiation methods [15] [16]. As a master regulator of neurogenesis, NGN2 overexpression can rapidly differentiate functional neurons from hPSCs, neural progenitors, or fibroblasts with high reproducibility, typically within 1-2 weeks [15] [17]. However, researchers often encounter challenges with variable maturation rates, unwanted cell populations, and protocol-dependent heterogeneity that can compromise experimental outcomes. This technical support center addresses these specific issues through troubleshooting guides and FAQs designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working within the context of optimizing neuronal maturation from iPSCs.

Key Research Reagents and Materials

The table below summarizes essential reagents for successful NGN2 neuronal differentiation:

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for NGN2 Neuronal Differentiation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Induction System | Doxycycline (Dox)-inducible NGN2 | Controls transgene expression; typically used at 1-3 μg/mL [18] [17] |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors | LDN-193189 (BMP inhibitor), SB431542 (TGF-β inhibitor), DAPT (Notch inhibitor) | Enhances neural induction purity and prevents progenitor contamination [17] [19] |

| Anti-proliferative Agents | Cytarabine (Ara-C), Mitomycin-C, Fluorouracil (5-FU) | Eliminates dividing progenitor cells and reduces clump formation [17] |

| Maturation Enhancers | GENtoniK cocktail (GSK2879552, EPZ-5676, NMDA, Bay K 8644) | Accelerates functional maturation through epigenetic and calcium signaling modulation [4] |

| Cryopreservation Aids | Rho-kinase (ROCK) inhibitor | Improves cell survival after freezing and thawing [17] |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Heterogeneous Neuronal Populations

Problem: Resulting cultures contain mixed neuronal subtypes or non-neuronal cells despite NGN2 expression.

Solutions:

- Implement FACS sorting: Isolate iPSCs with homogeneous NGN2 expression levels using linked GFP reporters before differentiation initiation. This addresses heterogeneity caused by variable transgene expression [16].

- Optimize NGN2 induction duration: Extend doxycycline-mediated NGN2 expression beyond standard protocols. Recent studies indicate that prolonged NGN2 dosage dramatically improves neuronal purity by more completely converting progenitors [18].

- Incorporate dual SMAD inhibition: Combine NGN2 programming with SMAD (LDN-193189, SB431542) and WNT inhibitors during early differentiation phases to generate patterned induced neurons (hpiNs) with more consistent excitatory glutamatergic identity [19].

- Use anti-proliferative agents: Include cytarabine (Ara-C) or similar compounds during replating to eliminate actively dividing neural progenitor cells that create contaminating niches [17].

Incomplete Neuronal Maturation

Problem: Neurons exhibit immature electrophysiological properties, simplified morphology, or fetal-like transcriptomic signatures even after extended culture.

Solutions:

- Apply maturation-accelerating cocktails: Implement the GENtoniK cocktail (GSK2879552 [LSD1 inhibitor], EPZ-5676 [DOT1L inhibitor], NMDA, and Bay K 8644 [LTCC agonist]) which targets both chromatin remodeling and calcium-dependent transcription to drive adult-like maturity [4].

- Validate with appropriate markers: Assess multiple maturity dimensions simultaneously:

- Extend culture duration: Maintain neurons for at least 100-150 days with appropriate trophic support, as human neurons follow protracted timelines regardless of induction method [20] [17].

Technical Variability Across Experiments

Problem: Inconsistent differentiation outcomes between replicates, batches, or laboratory sites.

Solutions:

- Use safe-harbor engineered lines: Employ iPSCs with NGN2 stably integrated into the AAVS1 locus rather than lentiviral delivery to minimize copy number variation and position effects [18] [17].

- Standardize plating conditions: Optimize and consistently maintain critical parameters:

- Implement quality controls: Perform rigorous genomic stability assessment post-reprogramming using SNP arrays rather than conventional karyotyping to detect subtle rearrangements that might affect differentiation consistency [16].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the typical efficiency and timeline for generating functional neurons using NGN2 programming?

NGN2 programming can generate neurons with neuronal morphology appearing within 2-4 days, with most cells exhibiting neuronal morphology by day 4 [17]. However, achieving functionally mature neurons with robust synaptic activity requires significantly longer culture periods—typically 28-56 days for basic electrophysiological properties, and up to 150 days for complete maturation resembling postnatal states [17] [4]. Efficiency can reach 75-90% glutamatergic neurons when optimized protocols are used [17].

Q2: Why do my NGN2-induced neurons show variable responses to depolarizing stimuli?

Neuronal responses to stimuli like KCl are highly maturation-dependent. Immature neurons (7-10 DIV) exhibit dramatically different electrophysiological properties and immediate early gene responses compared to more developed cultures (21+ DIV) [22]. This reflects natural development of calcium signaling, receptor composition, and synaptic connectivity. Consistently control for and report neuronal age in experiments, and consider using maturation-accelerating compounds like the GENtoniK cocktail for more consistent responses [4].

Q3: How can I minimize the presence of non-neuronal cells in my NGN2 cultures?

Persistent non-neuronal cells (often neural progenitors or astrocytes) typically result from:

- Incomplete NGN2-mediated conversion - address through extended NGN2 expression [18]

- Progenitor proliferation - suppressed using anti-mitotics like cytarabine or 5-fluorouracil [17]

- Insufficient patterning - improved by combining NGN2 with SMAD/WNT inhibition [19] Single-cell RNA sequencing can identify contaminating cell types for targeted troubleshooting [17].

Q4: What are the key differences between NGN2-programmed neurons and those from directed differentiation?

Table 2: Comparison of Neuronal Differentiation Methods

| Parameter | NGN2 Programming | Directed Differentiation |

|---|---|---|

| Timeline | 7-28 days for basic neurons [17] | Weeks to months for similar stages [15] |

| Efficiency | High (≥75% glutamatergic) [17] | Variable, often lower [15] |

| Heterogeneity | Lower with optimization [16] | Higher, multiple cell types [15] |

| Regional Identity | Mixed cortical/thalamic features [17] | More specific regional identities possible [15] |

| Technical Demand | Lower with engineered lines [17] | Higher, requires precise timing [15] |

Q5: Can NGN2 programming generate specific neuronal subtypes beyond generic glutamatergic neurons?

Yes, with additional patterning. While NGN2 alone predominantly produces excitatory neurons with mixed cortical and thalamic features [17], combining NGN2 with regionalizing factors can generate more specific subtypes:

- Cortical neurons: NGN2 + SMAD/WNT inhibition [19]

- Motor neurons: NGN2 with additional patterning factors [15]

- Sensory neurons: NGN2 with specific morphogens [15] The resulting neuronal identity should be validated through combination of marker expression (FOXG1 for forebrain, ISL1 for motor/sensory) and transcriptomic profiling [17].

Experimental Workflows and Signaling Pathways

Optimized NGN2 Neuronal Differentiation Workflow

Maturation Acceleration via GENtoniK Cocktail Mechanism

Successful generation of homogeneous glutamatergic neurons via NGN2 programming requires attention to three critical aspects: (1) starting cell quality with homogeneous NGN2 expression, (2) appropriate patterning during early differentiation, and (3) systematic maturation enhancement. By implementing the troubleshooting strategies and optimized protocols outlined in this technical guide, researchers can significantly improve the reproducibility and translational relevance of their iPSC-derived neuronal models for studying neurological disorders and screening therapeutic compounds.

DUAL SMAD inhibition represents a foundational methodology in human pluripotent stem cell (hPSC) research for efficiently directing cells toward neuronal lineages. By simultaneously blocking transforming growth factor–beta (TGF-β) and bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling pathways, this protocol enables robust and reproducible induction of neuroectoderm, serving as the basis for generating diverse brain region–specific neuronal subtypes [23]. The approach has become indispensable for both basic neuroscience research and translational applications, including its recent use in clinical trials for Parkinson's disease [23] [24].

Within the context of optimizing neuronal maturation from iPSCs, DUAL SMAD inhibition offers a unique advantage: it produces heterogeneous neural cultures that closely mimic developmental processes. Unlike direct differentiation methods that generate homogeneous neuronal populations, this approach yields cultures containing a mix of neurons, neural precursors, and glial cells through a stepwise differentiation process that passes through a neural stem cell stage [5]. This heterogeneity is particularly valuable for modeling complex neural environments and studying the interactions between different neural cell types during maturation.

Mechanism of Action: Core Signaling Pathways

Molecular Foundations of Neural Induction

During embryonic development, the formation of three germ layers—ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm—is orchestrated by a complex interplay of signaling pathways, primarily WNT/β-catenin, FGF, TGF-β, and BMP families [23]. Active TGF-β and BMP signaling normally prevent neuronal differentiation by maintaining pluripotency or diverting cells toward mesodermal and endodermal lineages. The DUAL SMAD inhibition protocol induces neuronal fate in hPSCs by simultaneously blocking both pathways, thereby eliminating signals necessary for pluripotency and mesendodermal fate induction [23].

The TGF-β and BMP pathways converge on intracellular SMAD proteins, which transmit extracellular signals to the nucleus upon phosphorylation. Phosphorylated SMAD proteins form complexes with SMAD4 and translocate to the nucleus to regulate gene expression. DUAL SMAD inhibition disrupts this process using specific inhibitors [23]:

- SB431542: A cell-permeable small molecule that inhibits TGF-β signaling by selectively targeting Activin receptor–like kinases ALK4, ALK5, and ALK7, thereby suppressing SMAD2/3 activation

- Noggin: An endogenous BMP antagonist that binds to and sequesters BMP ligands, preventing receptor activation

- LDN193189: A synthetic small-molecule inhibitor that targets ALK2/3/6 receptors, blocking phosphorylation of SMAD1/5/8

The outcome of this coordinated inhibition is the robust and reproducible induction of neural fate, with hPSCs exiting the pluripotent state and defaulting to a neuroectodermal lineage [23].

Figure 1: DUAL SMAD Inhibition Signaling Mechanism. Simultaneous inhibition of TGF-β and BMP pathways prevents SMAD phosphorylation and nuclear translocation, removing barriers to neural differentiation and enabling formation of heterogeneous neural cultures.

Experimental Protocols: Methodology and Workflows

Core DUAL SMAD Inhibition Protocol

The standard DUAL SMAD inhibition protocol for neural differentiation from iPSCs follows a well-established workflow with specific timing and reagent requirements. The process typically begins with undifferentiated iPSCs maintained under standard culture conditions, then transitions through defined stages of neural induction and maturation [5] [25].

Key Methodological Steps:

Initial Cell Plating: Undifferentiated iPSCs are dissociated into single cells and plated onto Matrigel-coated dishes in conditioned medium supplemented with ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 to promote cell survival [25].

Neural Induction: After 72 hours, cells are switched to knock-out serum replacement media (KSR) containing both Noggin (or LDN193189) and SB431542 to initiate neural induction [25].

Neural Precursor Formation: Treatment with DUAL SMAD inhibitors typically continues for 10-14 days, during which cells differentiate into neuroepithelial cells expressing PAX6 and other early neural markers [25].

Terminal Differentiation: Neural precursors can be further differentiated into specific neuronal subtypes through the addition of patterning factors and maturation media [5].

This protocol yields heterogeneous cultures containing a mix of central nervous system (CNS) progenitors and neural crest cells, with the initial plating density influencing the ratio of CNS versus neural crest progeny [25].

Workflow for Synchronized Neuronal Maturation

For researchers focusing specifically on neuronal maturation, a modified DUAL SMAD inhibition approach can generate temporally synchronized cortical neurons:

Figure 2: Synchronized Neuronal Maturation Workflow. This specialized protocol using DUAL SMAD inhibition followed by Notch inhibition enables generation of temporally synchronized cortical neurons for maturation studies.

This synchronized approach produces homogeneous populations of cortical neurons that mature gradually over months in vitro, exhibiting progressive increases in neurite complexity, electrophysiological maturity, and synaptic function [26]. The timeline mirrors the protracted development of human cortical neurons in vivo, providing a valuable model for studying maturation processes.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials

Table 1: Key Reagents for DUAL SMAD Inhibition Protocol

| Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| SB431542 | TGF-β pathway inhibitor; targets ALK4/5/7 receptors | Used at typical concentrations of 10-20 μM; critical for suppressing mesendodermal differentiation [23] [25] |

| Noggin | Recombinant BMP antagonist; binds and sequesters BMP ligands | Can be replaced by small molecule LDN193189 for more consistent results [23] |

| LDN193189 | Small molecule BMP inhibitor; targets ALK2/3/6 receptors | Often preferred over Noggin for higher purity and reproducibility [23] |

| Y-27632 | ROCK inhibitor; prevents apoptosis in dissociated cells | Essential for single-cell passaging; used at 5-10 μM [5] |

| Doxycycline | Tetracycline analog; induces transgene expression in Tet-ON systems | Used at 1-2 μg/mL for inducible differentiation protocols [5] |

| DAPT | γ-secretase inhibitor; blocks Notch signaling | Used for synchronized neurogenesis at progenitor stage [26] |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Low Neural Induction Efficiency

Problem: Poor yield of neural progenitor cells despite DUAL SMAD inhibition treatment.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Inadequate inhibitor concentration: Validate working concentrations of SB431542 (typically 10-20 μM) and Noggin/LDN193189 through dose-response testing

- Improper initial cell density: Optimize plating density as this significantly affects neural conversion efficiency and the ratio of CNS versus neural crest progeny [25]

- Cell line variability: Different iPSC lines may show varying differentiation efficiencies; consider testing multiple lines or optimizing protocol for specific lines

- Pluripotency maintenance: Ensure iPSCs are in undifferentiated state before initiation of neural induction

Excessive Heterogeneity or Unwanted Cell Types

Problem: Cultures contain unexpected non-neural cell types or incorrect neural subtypes.

Troubleshooting Strategies:

- Validate patterning factors: Ensure appropriate anterior-posterior and dorsal-ventral patterning cues are applied after initial neural induction [23]

- Timing of protocol steps: Precise timing of inhibitor treatment and growth factor addition is critical; extend DUAL SMAD inhibition if persistent pluripotent cells observed

- Cell sorting strategies: Implement fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) using neural surface markers if higher purity is required [27]

- Metabolic selection: Consider using selective media conditions that favor neural cell survival

Poor Neuronal Maturation

Problem: Neurons fail to develop mature electrophysiological properties or synaptic connectivity.

Optimization Approaches:

- Extended culture duration: Human neurons require extended time (months) to mature fully; ensure adequate culture maintenance [26]

- Epigenetic modulation: Consider transient inhibition of EZH2, EHMT1/2, or DOT1L at progenitor stage to precociously enhance maturation [26]

- Activity-dependent stimulation: Implement chronic stimulation protocols to promote functional maturation

- Co-culture systems: Consider astrocyte co-cultures or conditioned media to provide trophic support

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: How does DUAL SMAD inhibition compare to NGN2 overexpression for neuronal differentiation?

A: These methods produce distinctly different neural cultures. DUAL SMAD inhibition generates heterogeneous cultures containing a mix of neurons, neural precursors, and glial cells through a developmental process that includes neural stem cell stages. In contrast, NGN2 overexpression produces more homogeneous cultures composed predominantly of mature neurons without going through extended progenitor stages. Transcriptomic analyses reveal enrichment of neural stem cell and glial markers in DUAL SMAD inhibition cultures, while NGN2 cultures show elevated markers for cholinergic and peripheral sensory neurons [5].

Q: What is the typical efficiency of neural conversion using DUAL SMAD inhibition?

A: When properly optimized, the protocol can achieve very high efficiencies of neural conversion. Original reports demonstrated greater than 80% PAX6+ neural progenitor cells using combined Noggin and SB431542 treatment, compared to less than 10% with either inhibitor alone [25]. Efficiency can be monitored using neural markers like PAX6, SOX1, and SOX2 at early timepoints.

Q: Can DUAL SMAD inhibition generate region-specific neuronal subtypes?

A: Yes, the protocol serves as a foundation for generating diverse brain region-specific neuronal subtypes. By default, DUAL SMAD inhibition produces anterior (forebrain) neural progenitors that predominantly give rise to cortical neurons. Specific neuronal subtypes can be generated by adding appropriate patterning factors – for example, caudalizing agents like WNT activators or retinoic acid can shift identity toward midbrain, hindbrain, or spinal cord fates [23].

Q: How long does complete neuronal maturation take using this method?

A: Neuronal maturation following DUAL SMAD inhibition follows a protracted timeline that mirrors human development. While early neuronal markers appear within 1-2 weeks, full electrophysiological maturation with repetitive action potentials and functional synapses typically requires 50-100 days in vitro, with continued maturation occurring over even longer periods [26]. This slow maturation timeline reflects cell-intrinsic mechanisms that include specific epigenetic barriers [26].

Q: What are the key advantages of DUAL SMAD inhibition for disease modeling?

A: The method offers several advantages: (1) It produces heterogeneous cultures that better mimic the cellular diversity of neural tissue; (2) It follows developmental principles, allowing study of disease processes across different developmental stages; (3) The inclusion of glial precursors enables modeling of neuron-glia interactions; (4) It has been validated across numerous hPSC lines and in clinical-grade applications [23].

Advanced Applications: Integration with Emerging Technologies

CRISPR/Cas9 Engineering in DUAL SMAD Inhibition

The combination of DUAL SMAD inhibition with CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing enables powerful approaches for disease modeling and lineage tracing. For example, researchers have successfully generated knock-in reporter lines where fluorescent proteins are inserted into endogenous neural genes such as tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), allowing specific identification and purification of dopaminergic neurons following differentiation [27]. This integration provides:

- Precise lineage tracking: Endogenous fluorescent reporters enable real-time monitoring of neuronal differentiation and maturation

- Cell sorting capabilities: FACS purification of specific neuronal populations from heterogeneous cultures

- Disease modeling: Introduction of disease-associated mutations into isogenic iPSC lines

- High-throughput screening: Enables quantitative analysis of differentiation outcomes

3D Organoid Development

DUAL SMAD inhibition serves as the foundational step for generating more complex 3D neural organoids that recapitulate aspects of human brain development and disease. These 3D models overcome limitations of 2D cultures by better mimicking cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix interactions, enabling study of higher-order cellular organization and network dynamics [28] [29]. Recent advances include:

- Disease-specific organoids: Modeling dementia disorders like Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and ALS/FTD

- Multi-regional assemblies: Combining organoids representing different brain regions

- Integration of non-neural lineages: Incorporating microglia or vascular cells for more complete models

Table 2: Characterization of Neural Cultures Following DUAL SMAD Inhibition

| Parameter | Typical Outcome | Measurement Method | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neural Conversion Efficiency | >80% PAX6+ cells | Immunocytochemistry, Flow Cytometry | [25] |

| Culture Composition | Mixed neurons, neural precursors, glial cells | Transcriptomic Analysis, Immunostaining | [5] |

| Action Potential Development | 50-100 days for repetitive firing | Patch Clamp Electrophysiology | [26] |

| Synaptic Function | mEPSCs detectable by 50-75 days | Electrophysiology, Immunostaining | [26] |

| Neurite Complexity | Progressive increase over 100 days | Morphometric Analysis | [26] |

| Cortical Neuron Purity | ~90% TBR1+ with synchronization | scRNA-seq, Immunostaining | [26] |

A critical challenge in iPSC research is selecting a differentiation and screening protocol that aligns with the specific research objective. The choice between building a high-content disease model or a platform for high-throughput screening (HTS) dictates every subsequent experimental parameter. This guide provides troubleshooting and procedural advice to help you match your method to your goal within the context of optimizing neuronal maturation from iPSCs.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. How do I decide between a 2D monolayer and a 3D organoid system for my disease modeling project? The decision hinges on the biological question. Use 2D monolayers for investigating cell-autonomous mechanisms, high-content imaging, and electrophysiological studies at the single-cell level. They offer simplicity and reproducibility. Opt for 3D organoids when your research question involves complex cell-cell interactions, tissue-level architecture, and microenvironmental effects, as they more accurately mimic the cellular complexity of the developing brain [30] [31]. However, be prepared to address higher heterogeneity and technical complexity.

2. What are the key considerations for adapting a neuronal differentiation protocol for high-throughput screening? The primary considerations are scalability, reproducibility, and quantifiability. The protocol must generate highly uniform cultures in multi-well plates (e.g., 96 or 384-well format) with minimal well-to-well variability. The readout, whether it's cell survival, neurite outgrowth, or a simplified transcriptional signature, must be robust and amenable to automation. Reductionist systems that focus on a key, quantifiable phenotype are often more successful than highly complex models for HTS [32].

3. Why does my iPSC-derived motor neuron model fail to show a disease-relevant phenotype, even with a patient-derived line? The absence of a phenotype is a common hurdle. First, verify that your neurons are fully mature, as many disease phenotypes are age-dependent. Consider extending the maturation period. Second, assess whether non-cell-autonomous factors (e.g., from glial cells) are missing from your culture system. Introducing astrocytes or microglia might be necessary. Finally, implement more sensitive phenotypic assays, such as longitudinal live-cell imaging to track subtle changes in neurite health or single-cell RNA sequencing to identify cryptic transcriptional shifts [32] [33].

4. How can I improve the consistency of neuronal differentiation across multiple iPSC lines? Line-to-line variability is a major challenge. To mitigate it, ensure all your iPSC lines have undergone rigorous quality control for karyotype and pluripotency. Use a highly standardized, possibly automated, differentiation protocol. For spinal motor neuron differentiation, leveraging a neuromesodermal progenitor (NMP) intermediate has been shown to enhance the efficiency and posterior identity of the resulting neurons, improving consistency [34]. Additionally, maintain consistent cell seeding densities and batch-test all critical reagents.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Poor Survival of Mature Neurons in Long-Term Culture

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Toxic metabolite accumulation in the culture medium.

- Solution: Optimize the feeding schedule. For mature neurons, consider half-medium changes every 2-3 days instead of full changes to avoid shocking the cells. Test the addition of antioxidant supplements like N-acetylcysteine.

- Cause 2: Inadequate neurotrophic support.

- Solution: Supplement the maturation medium with a combination of neurotrophic factors. Common choices include BDNF, GDNF, and CNTF, typically in the range of 10-20 ng/mL. Re-evaluate and titrate the concentrations for your specific neuronal subtype.

- Cause 3: Excessive stress from over-dissociation or passaging.

- Solution: Mature post-mitotic neurons are sensitive to passaging. Instead, plate neural progenitors and allow them to differentiate and mature in the same well. Use gentle reagent-based methods for any necessary dissociation.

Issue: High Well-to-Well Variability in a High-Throughput Screening Assay

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Inconsistent starting cell population.

- Solution: Use a large, master bank of pre-differentiated neural progenitor cells (NPCs) that has been thoroughly quality-controlled. Thaw a single vial for an entire screen to ensure a uniform starting point. Employ automated cell counters and dispensers for precise and consistent plating.

- Cause 2: Edge-effect evaporation in multi-well plates.

- Solution: Use tissue culture-treated plates designed for HTS. Fill the outer wells with PBS only and do not use them for experimental data. Consider using plate seals during incubation periods.

- Cause 3: Inconsistent compound dispensing or dosing.

- Solution: Use automated liquid handlers for compound addition. Include control wells that receive only the vehicle (e.g., DMSO) dispersed by the same system to account for any dispensing effects.

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

Detailed Protocol 1: Large-Scale Phenotypic Screening for Motor Neuron Survival

This protocol is adapted from a recent large-scale study that successfully modeled sporadic ALS [32].

Workflow Diagram: High-Throughput Screening Pipeline for Motor Neuron Health

Methodology:

- iPSC Culture and Quality Control: Maintain a curated library of iPSC lines from patients and healthy controls. All lines must undergo rigorous quality control, including genomic integrity checks (e.g., karyotyping), pluripotency verification (e.g., expression of OCT3/4, NANOG), and trilineage differentiation potential [32].

- Motor Neuron Differentiation: Employ a optimized five-stage spinal motor neuron differentiation protocol. Adapt a well-established method to generate high-purity cultures [32] [34].

- Key Steps: Induce neuromesodermal progenitors (NMPs) with CHIR99021 (a GSK3β inhibitor) and growth factors. Pattern towards posterior spinal identity. Differentiate into motor neuron progenitors and then mature motor neurons.

- Quality Control: Validate cultures by immunostaining for motor neuron markers (ChAT, MNX1/HB9, ISL1, TUJ1). Aim for >90% purity. Assess functional maturity via patch-clamp electrophysiology to confirm action potential firing [32] [34].

- Phenotypic Screening with Live-Cell Imaging: Plate mature motor neurons in 96 or 384-well plates. Use a motor neuron-specific reporter (e.g., HB9::GFP) for selective tracking. Place plates in an automated live-cell imaging system. Acquire images every 4-24 hours over 7-14 days to track survival and neurite degeneration [32].

- Compound Library Addition: At a pre-defined maturation stage, add drugs from your library. Include positive controls (e.g., 10 µM Riluzole) and vehicle controls (e.g., 0.1% DMSO). The study screening over 100 clinical trial drugs found that a combination of Riluzole, Memantine, and Baricitinib was effective [32].

- Data Analysis: Use automated image analysis software to quantify:

- Motor neuron survival over time.

- Neurite length and branching complexity.

- Correlate in vitro phenotypes with donor clinical data (e.g., survival time).

Quantitative Data from Screening Campaigns

| Screening Parameter | Performance Metric | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Culture Purity | >92% motor neurons (ChAT+, MNX1+, TUJ1+) [32] | Essential for cell-autonomous effect studies. |

| Phenotype Correlation | Accelerated neurite degeneration correlated with donor survival [32] | Validates clinical relevance of the model. |

| Clinical Trial Drug Re-Creation | ~3% of tested drugs showed efficacy [32] | Reflects actual clinical trial failure rates, validating model predictive power. |

| Key Effective Drugs | Riluzole, Memantine, Baricitinib (combinatorial) [32] | Identified as promising therapeutic combination for SALS. |

Detailed Protocol 2: Establishing a High-Content Model for Hereditary Sensory Neuropathy

This protocol uses 3D organoids to model a complex neurodevelopmental disorder, HSAN IV [33].

Workflow Diagram: Disease Modeling with Isogenic Control iPSC Lines

Methodology:

- Generate Isogenic Control Lines: Use CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing to correct the disease-causing mutation (e.g., in the NTRK1 gene) in the patient-derived iPSCs. This creates a genetically matched control, isolating the mutation as the only variable [33].

- Dorsal Root Ganglion (DRG) Organoid Differentiation: Differentiate both patient and isogenic control iPSCs into 3D DRG organoids, which contain sensory neurons and supporting glial cells.

- Key Steps: Guide iPSCs through a neural crest stem cell pathway. Aggregate cells to form 3D structures and pattern towards a sensory neuron fate using specific morphogens [33].

- Phenotypic Analysis: Compare patient and isogenic organoids across multiple dimensions.

- Lineage Specification: Analyze the balance of neuronal and glial differentiation by immunostaining for markers like ISLET1/BRN3A (sensory neurons) and FABP7 (glia). The HSAN IV model showed premature gliogenesis [33].

- Maturation: Assess expression of mature sensory markers (TRKA, TRPV, CGRP) and evaluate axonal outgrowth.

- Functional Assays: Perform calcium imaging to assess neuronal activity and response to stimuli.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Key materials and reagents used in advanced iPSC-based neuronal research.

| Item | Function/Application | Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Integrating Reprogramming Vectors | Generating clinical-grade iPSCs without genomic integration. | Sendai Virus Vectors: High efficiency, can be diluted out [31] [37]. Episomal Plasmids: Cost-effective, no viral components [32] [31]. |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors/Activators | Directing differentiation by modulating key signaling pathways. | CHIR99021: GSK3β inhibitor, activates Wnt signaling for NMP induction [34]. SMAD Inhibitors (e.g., A-83-01): Promotes neural induction [31] [34]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System with High-Fidelity Variants | Precise genome editing for creating isogenic controls. | SpCas9-HF1 / eSpCas9(1.1): Engineered for reduced off-target effects [36]. AI gRNA Design Tools (e.g., DeepHF): Improve on-target efficiency prediction [35] [36]. |

| Tandem Mass Tag (TMT) Labeling | Multiplexed proteomic analysis from limited samples like neurospheres. | Allows comparative analysis of up to 10+ samples simultaneously, maximizing data yield [30]. |

| Longitudinal Live-Cell Imaging Systems | Automated, non-invasive tracking of cell health and phenotype over time. | Essential for quantifying dynamic processes like neurodegeneration in high-throughput screens [32]. |

The choice between two-dimensional (2D) monolayers and three-dimensional (3D) organoid models is a critical decision in experimental design, particularly within the context of optimizing neuronal maturation from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). While 2D cultures have long been the workhorse for high-throughput assays and straightforward mechanistic studies, 3D organoids are revolutionizing the field by recapitulating the complex architecture and cellular interactions of the human brain [38] [39]. This technical support guide provides a structured comparison, troubleshooting advice, and detailed protocols to help researchers navigate these advanced culture systems effectively.

Comparative Analysis: 2D Monolayers vs. 3D Organoids

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of each model system to inform your experimental planning.

| Feature | 2D Monolayer Cultures | 3D Organoid Models |

|---|---|---|

| Core Structure | Single layer of cells on a flat, rigid plastic/glass surface [38] | Self-organizing 3D structures that mimic organ architecture [38] [39] |

| Cellular Complexity & Microenvironment | Limited cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions; lacks physiological tissue context [38] | Recapitulates complex cell-cell interactions and a more native tissue microenvironment [38] [20] |

| Key Advantages | Simplicity, cost-effectiveness, suitability for high-throughput drug and toxicity screening [38] [39] [40] | Models human-specific developmental processes, patient-specific disease phenotypes, and complex tissue-level functions [38] [20] [40] |

| Primary Limitations | Poor translation to in vivo human physiology; fails to model tissue-level properties [38] | Batch-to-batch variability, hypoxic cores leading to necrosis, extended culture times for maturation (≥6 months) [38] [20] |

| Ideal Applications | High-content imaging, electrophysiology (patch clamp), initial drug efficacy/toxicity screening, genetic manipulation [38] [40] | Disease modeling (e.g., Parkinson's, Alzheimer's), studying cell-cell interactions (e.g., neuro-immune), investigation of complex tissue development [38] [20] [40] |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing 3D Organoid Culture Challenges

Problem: Central Necrosis and Hypoxic Cores

- Cause: Limited diffusion of oxygen and nutrients into the organoid's core, especially in larger structures [20].

- Solution: Integrate bioengineering approaches. Use spinning bioreactors or orbital shakers to improve medium convection. Consider co-culturing with endothelial cells to encourage the formation of vascular networks, or use microfluidic devices to enhance nutrient delivery [20].

Problem: Incomplete or Arrested Maturation

- Cause: Organoids often remain at a fetal-to-early postnatal stage, even after extended culture, lacking adult neuronal and glial markers [20].

- Solution: Extend culture periods to ≥6 months with careful monitoring. Incorporate microenvironmental modulators, such as electrical stimulation or specific growth factor regimens, to promote gliogenesis and synaptic refinement. Employ co-culture systems with microglia or astrocytes to support mature network activity [20].

Problem: High Batch-to-Batch Variability

- Cause: Inconsistencies in iPSC line differentiation potential, reagent lots, and manual handling during complex protocols [38] [20].

- Solution: Standardize protocols and implement rigorous quality control. Use defined matrices and growth factors. For colorectal organoids, ensure prompt tissue processing (<6-10 hours) or optimized cryopreservation methods to maintain consistent cell viability [41].

Guide 2: Addressing 2D Monolayer Culture Challenges

Problem: Poor Differentiation Efficiency into Specific Neuronal Subtypes

- Cause: Inadequate or imprecise patterning signals during neural induction and differentiation [38] [40].

- Solution: Employ well-established, precise patterning protocols. For midbrain dopaminergic neurons (critical for Parkinson's disease research), use a floor plate-based strategy with morphogens like Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) and WNT activators, followed by maturation with BDNF and GDNF [40].

Problem: Lack of Physiologically Relevant Cellular Interactions

- Cause: The simplified 2D environment lacks the diverse cell types and spatial organization found in vivo [38].

- Solution: Develop co-culture systems. For blood-brain barrier (BBB) modeling, co-culture iPSC-derived brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMECs) with pericytes, neurons, and astrocytes to create a more functional barrier in a dish [38].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: When should I choose a 2D model over a 3D organoid model for my drug screening campaign? Choose a 2D model for primary, high-throughput screening of large compound libraries due to its simplicity, lower cost, and easier data readouts. Reserve 3D organoid models for secondary, more physiologically relevant validation of hits identified in the 2D screen, as they can better predict human-specific drug responses and toxicities [38] [39] [40].

Q2: How can I accurately assess the maturity and functionality of my brain organoids? A multimodal assessment framework is essential [20].

- Structural: Use immunofluorescence for cortical layer markers (SATB2 for upper layers, TBR1/CTIP2 for deep layers) and synaptic proteins (PSD-95, SYB2) [20].

- Cellular Diversity: Employ fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) and single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) to quantify neurons, astrocytes (GFAP, S100β), and oligodendrocytes (MBP, O4) [20].

- Functional: Use multielectrode arrays (MEAs) to record synchronized network activity and calcium imaging to visualize dynamic activity across cell populations [20].

Q3: What are the critical steps for successfully generating patient-derived organoids (PDOs) from colorectal tissue?

- Tissue Procurement: Transfer samples immediately in cold antibiotic-supplemented medium to preserve viability [41].

- Processing Time: Process tissue within 6-10 hours. If delayed, use short-term refrigerated storage with antibiotics or cryopreservation, noting a potential 20-30% variability in cell viability between these methods [41].

- Established Culture: Use a matrix like Matrigel and culture in medium supplemented with essential growth factors (e.g., EGF, Noggin, R-spondin1) to support long-term expansion of epithelial cell diversity [41].

Q4: Can 3D organoids model the blood-brain barrier (BBB)? Current brain organoids generally lack a fully functional BBB, which is a major limitation for studying drug penetration and neurovascular interactions. However, rudimentary BBB units with endothelial tubes, pericytes, and astrocytic endfeet have been observed in some advanced models. A more direct approach is to construct a BBB in a dish using iPSC-derived astrocytes, neurons, and endothelial cells in a specialized 2D or 3D setup [38] [20].

Experimental Workflows and Signaling Pathways

Workflow 1: Generating Neural Stem Cells (NSCs) from iPSCs for 2D Culture

This foundational protocol is used to create NSCs, which can then be further differentiated into various neural lineages [38].

Workflow 2: Key Signaling Pathway for Midbrain Patterning

This pathway is critical for directing stem cells to become midbrain dopaminergic neurons, both in 2D and for the generation of midbrain organoids [40].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Category | Function in 2D/3D Cultures | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Growth Factors (FGF-2, EGF, BDNF, GDNF) | Promote NSC self-renewal, proliferation, and neuronal survival/maturation [38] [40]. | Essential in NSC derivation protocol [38]; BDNF/GDNF used for maturation of midbrain dopaminergic neurons [40]. |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors/Activators (Noggin, R-spondin) | Modulate key signaling pathways (e.g., BMP, WNT) to direct cell fate. | Noggin and R-spondin1 are key components in long-term colon organoid culture medium [41]. |

| Defined Extracellular Matrices (e.g., Matrigel) | Provide a 3D scaffold that supports complex tissue morphogenesis and polarization. | Used as a scaffold for embedding and growing colorectal and brain organoids [41] [20]. |

| Chemically Defined Media Supplements (B27, N2) | Provide essential nutrients, hormones, and lipids for the survival and differentiation of neural cells. | Used in the medium for neural rosette and NSC formation from EBs [38]. |

| Cell Type-Specific Markers (SOX2, Nestin, PAX6, TBR1, GFAP) | Enable characterization of undifferentiated stem cells, neural progenitors, and differentiated neurons/glia via immunostaining. | SOX2/Nestin identify NSCs; TBR1 marks deep-layer neurons; GFAP identifies astrocytes [38] [20]. |

Overcoming Immaturity: Strategies to Enhance Reproducibility and Functional Output

The use of Neurogenin-2 (NGN2) programming to generate induced neurons (iNs) from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) has revolutionized neurological disease modeling and drug screening. This transcription factor-driven approach significantly expedites neuronal production compared to traditional directed differentiation methods, typically yielding functional neurons within weeks rather than months [42]. However, a significant challenge persists: substantial molecular heterogeneity within the resulting neuronal populations. Recent single-cell transcriptomic studies have revealed that NGN2-induced neurons (NGN2-iNs) often comprise multiple transcriptionally distinct populations, including neurons with central nervous system (CNS) features alongside unexpected peripheral nervous system (PNS) lineages [43]. This heterogeneity stems primarily from variable NGN2 expression levels and inconsistent transgene integration across cell populations [43] [16]. For researchers aiming to produce reproducible, clinically relevant models for neurological disorders, controlling this heterogeneity is paramount. This technical guide addresses the key sources of variability in NGN2 programming and provides evidence-based troubleshooting strategies to achieve homogeneous, predictable neuronal differentiation outcomes.

FAQs: Core Concepts and Problem Identification

Q1: Why does significant heterogeneity persist in my NGN2-induced neurons despite using a standardized protocol?

Recent single-cell RNA sequencing studies demonstrate that NGN2-induced neurons (NGN2-iNs) exhibit inherent molecular heterogeneity, containing multiple distinct neuronal subtypes rather than a uniform population. This heterogeneity includes cells expressing markers of both central and peripheral nervous system lineages [43]. The primary drivers identified are:

- Variable NGN2 expression levels: The dosage and duration of NGN2 expression directly influence neuronal fate acquisition [43].

- Inconsistent transgene integration: Conventional lentiviral methods result in random integration with varying copy numbers across cells [16].

- Protocol-dependent factors: The use of different small molecules, plating densities, and astrocyte co-culture conditions can further contribute to heterogeneity [17].

This heterogeneity is observed across multiple iPSC clones and lines from different individuals, confirming it as an intrinsic challenge in NGN2 programming systems [43].

Q2: How does heterogeneity impact the reliability of my disease modeling and drug screening applications?

Neuronal heterogeneity can significantly confound experimental results in several ways:

- Variable electrophysiological properties: Different neuronal subtypes exhibit distinct functional characteristics that can mask or mimic disease phenotypes.

- Inconsistent drug responses: Heterogeneous cultures yield unpredictable compound effects due to varying receptor expression and signaling pathways across neuronal subtypes.

- Reduced reproducibility: Batch-to-batch variability increases experimental noise, requiring larger sample sizes and complicating data interpretation [43] [16].

For high-content screening and precise disease modeling, achieving defined neuronal populations is essential for generating statistically robust, interpretable data.

Q3: What are the most effective strategies to minimize heterogeneity at the genetic engineering stage?

The most impactful approaches focus on controlling NGN2 expression at the integration level:

- Safe-harbor integration: Targeting the AAVS1 locus ensures consistent transgene expression and minimizes position effects [17] [44].

- Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS): Isolating cells with homogeneous NGN2-GFP expression levels using a T2A-linked reporter system [16].

- Clonal selection: Expanding single-cell clones to establish lines with identical integration patterns [16].

These methods directly address the fundamental issue of variable transgene expression that underlies much of the observed heterogeneity.

Troubleshooting Guides: Practical Solutions for Common Scenarios

Problem: Heterogeneous NGN2 Expression Despite Selection

Issue: After antibiotic selection, NGN2 expression remains variable upon induction, leading to inconsistent neuronal differentiation.

Solutions:

Implement FACS sorting for homogeneous expression:

- Use a bicistronic vector with NGN2-T2A-GFP

- Induce with doxycycline for 12 hours before sorting

- Isolate the median GFP-expressing population ("GFPsort" gate) to eliminate both negative and ultra-high expressers [16]

- Expand this sorted pool for consistent differentiation experiments

Apply stringent clonal selection:

- After FACS sorting, plate individual cells into 96-well plates

- Expand single-cell clones and validate consistent NGN2 expression upon induction

- Select clones with minimal expression heterogeneity for long-term use [16]

Utilize commercial engineered lines:

- Consider established lines like iP11N or iNgn2-dCas9-KRAB-CloneG12 with targeted AAVS1 integration for more predictable results [17]

Table 1: Comparison of NGN2 Expression Control Methods

| Method | Key Advantage | Implementation Time | Effectiveness | Technical Demand |

|---|---|---|---|---|