Patient-Specific Disease Modeling with Stem Cells: Bridging the Gap Between Bench and Bedside

Patient-specific disease modeling, particularly using induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), is revolutionizing biomedical research and drug development.

Patient-Specific Disease Modeling with Stem Cells: Bridging the Gap Between Bench and Bedside

Abstract

Patient-specific disease modeling, particularly using induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), is revolutionizing biomedical research and drug development. This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals, exploring the foundational principles of stem cell-based models and their advantages over traditional systems. It delves into advanced methodological applications across neurology, cardiology, and metabolic diseases, while addressing key challenges in model maturity, standardization, and scalability. The content further examines rigorous validation frameworks and comparative analyses with animal models and immortalized cell lines, offering insights into how these human-relevant systems are accelerating therapeutic discovery and paving the way for personalized medicine.

The New Paradigm: Foundations of Stem Cell-Based Disease Modeling

Historical Foundations and Core Concepts

The field of pluripotent stem cells is built upon the fundamental principle that most somatic cells retain a complete genetic blueprint, with cellular diversity arising from reversible epigenetic mechanisms rather than irreversible genetic changes [1]. The conceptual journey began with John Gurdon's seminal somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) experiments in 1962, which demonstrated that a nucleus from a differentiated frog cell could generate entire tadpoles when transplanted into an enucleated egg [1]. This pivotal work established that cellular differentiation does not involve irreversible loss of genetic potential.

The isolation of mouse embryonic stem cells (ESCs) in 1981 by Evans and Kaufman and later human ESCs (hESCs) by James Thomson in 1998 provided the first in vitro platforms for studying pluripotency [2] [1]. However, the ethical concerns surrounding embryo destruction for hESC derivation prompted the search for alternatives. The field transformed in 2006 when Takahashi and Yamanaka discovered that introducing four transcription factors—Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc (OSKM)—could reprogram mouse fibroblasts into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [3] [1]. This breakthrough was successfully replicated with human cells in 2007 by both Yamanaka's group (using OSKM) and Thomson's group (using OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, and LIN28) [4] [1], establishing iPSCs as a revolutionary tool that bypassed ethical concerns while enabling patient-specific disease modeling.

Pluripotent stem cells are defined by two essential properties: self-renewal, the capacity for unlimited division while maintaining the undifferentiated state, and pluripotency, the ability to differentiate into derivatives of all three embryonic germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm) [2]. These properties make them indispensable for studying human development, disease mechanisms, and regenerative medicine.

Technical Comparison of Pluripotent Stem Cell Types

Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs)

ESCs are derived from the inner cell mass of pre-implantation blastocysts [2]. They represent the gold standard for pluripotency and possess extensive self-renewal capacity [2]. Their isolation typically involves microsurgical dissection or immunological targeting of trophoblast cells to separate the inner cell mass [2]. ESCs have been instrumental in foundational studies of early human development and differentiation pathways. However, their clinical application faces significant hurdles, including ethical controversies related to embryo destruction, potential for immune rejection upon transplantation since they are genetically distinct from recipients, and strict regulatory constraints governing their use [2] [5].

Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs)

iPSCs are generated by reprogramming somatic cells through the forced expression of specific transcription factors, effectively returning them to an embryonic-like pluripotent state [5] [1]. The core advantage of iPSC technology lies in its ability to create patient-specific cell lines that reflect the individual's genetic background, making them invaluable for personalized disease modeling and potentially avoiding immune rejection in autologous transplantation [5] [6]. Additionally, they circumvent the major ethical issues associated with ESCs [5].

Despite these advantages, iPSC technology faces its own challenges. The reprogramming process can introduce genetic abnormalities and carries a potential tumorigenic risk, particularly when using oncogenic factors like c-Myc or if partially reprogrammed cells remain in the final population [3] [5]. iPSCs may also retain epigenetic memory of their tissue of origin, which can influence their differentiation potential [5]. Furthermore, the reprogramming process has historically been inefficient, though methods have improved significantly [5].

Table 1: Comparison of Embryonic and Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells

| Feature | Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) | Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Inner cell mass of blastocyst [2] | Reprogrammed somatic cells (e.g., skin, blood) [5] |

| Reprogramming Factors | N/A (naturally occurring) | OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC (OSKM) or OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, LIN28 (OSNL) [4] [3] [1] |

| Key Advantages | Gold standard for pluripotency [5] | Patient-specific; avoids ethical concerns of ESCs; suitable for autologous therapy [5] [6] |

| Major Challenges | Ethical controversies; immune rejection in recipients; tumorigenesis [2] [5] | Genetic instability; tumorigenic risk; epigenetic memory; lower efficiency in some protocols [3] [5] |

| Primary Applications | Early development studies; differentiation paradigm [2] | Disease modeling; drug screening; personalized regenerative medicine [5] [6] |

The Molecular Machinery of Reprogramming

Core Mechanisms and Dynamics

The reprogramming of somatic cells to iPSCs is not a simple reversal of development but involves profound remodeling of the epigenetic landscape and gene expression networks [1]. The process typically occurs in two broad phases: an early, stochastic phase where somatic genes are silenced and early pluripotency genes activated, followed by a late, more deterministic phase where the core pluripotency network is stabilized [1]. The Yamanaka factors (OSKM) function as pioneer transcription factors that can bind to condensed chromatin and initiate its opening, allowing access to other transcriptional regulators [1].

During reprogramming, cells undergo mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET), a critical step involving cadherin switching and cytoskeletal reorganization [1]. The process also involves global epigenetic changes, including DNA demethylation at pluripotency gene promoters and histone modification shifts that favor an open chromatin state [1]. Metabolic reprogramming from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis also occurs, mirroring the metabolic state of ESCs [1]. Additionally, somatic cell identity factors must be silenced while the endogenous pluripotency network (including OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG) becomes autonomously activated [1].

Reprogramming Methodologies and Delivery Systems

Significant progress has been made in developing safer and more efficient reprogramming methods. Early approaches used integrating retroviral and lentiviral vectors, which posed risks of insertional mutagenesis and oncogene activation [4] [3]. Current non-integrating methods include:

- Sendai Virus: A replication-deficient RNA virus that does not integrate into the host genome [4].

- Synthetic mRNA: Transient delivery of modified mRNA encoding reprogramming factors [4].

- Episomal Plasmids: DNA vectors that replicate extrachromosomally and are gradually diluted through cell divisions [3].

- Proteins: Direct delivery of recombinant reprogramming transcription factors [3].

- Small Molecules: Chemical compounds that can replace some transcription factors and enhance reprogramming efficiency [3] [1].

Table 2: Key Reprogramming Delivery Systems

| Delivery System | Genetic Material | Genomic Integration | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retrovirus | RNA | Yes | High efficiency [3] | Integration; silencing; tumorigenesis risk [3] |

| Lentivirus | RNA | Yes | Can infect non-dividing cells [3] | Integration; potential insertional mutagenesis [3] |

| Sendai Virus | RNA | No | High efficiency; no integration [4] | Require clearance; immunogenic potential [4] |

| Synthetic mRNA | RNA | No | High safety; controlled timing [4] | Requires multiple transfections; immunogenic [4] |

| Episomal Plasmid | DNA | No | Simple delivery; low cost [3] | Low efficiency; potential integration [3] |

| Recombinant Protein | Protein | No | Highest safety; no genetic material [3] | Very low efficiency; challenging delivery [3] |

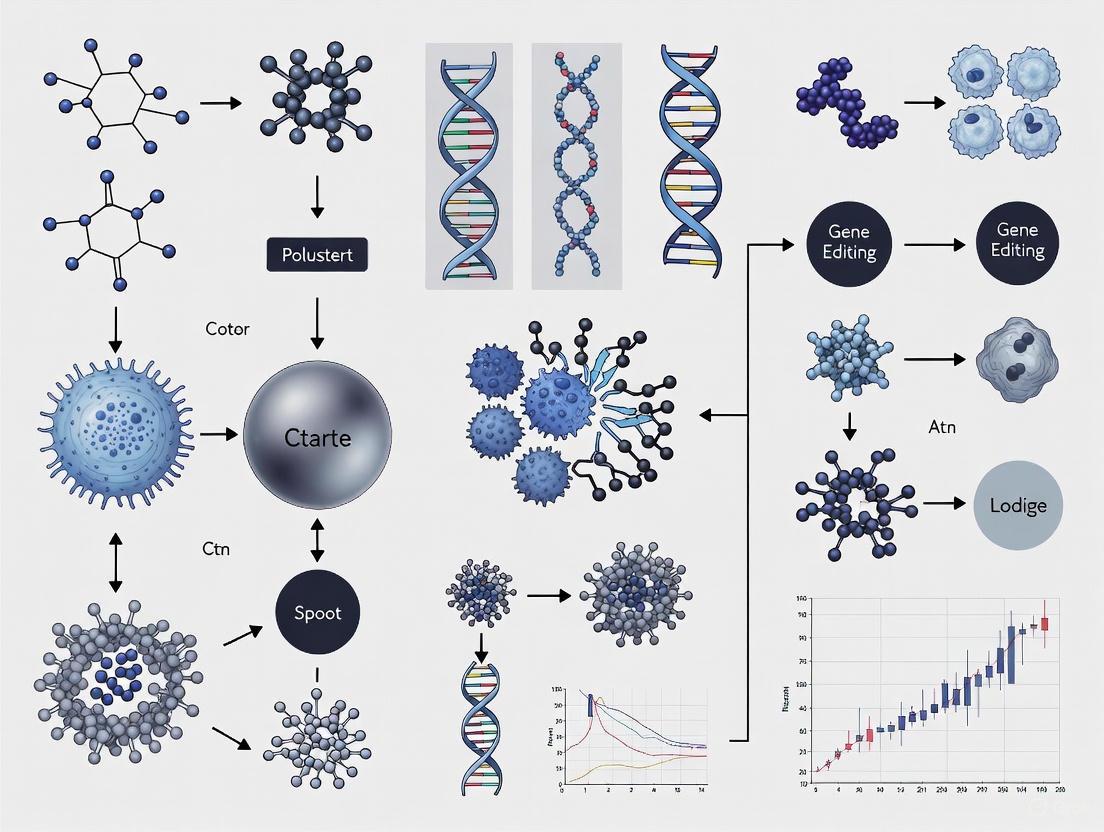

Reprogramming Mechanism Overview

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Protocols

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for iPSC Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC (OSKM) [3] [1] | Core transcription factors inducing pluripotency |

| Reprogramming Enhancers | Valproic acid (VPA), Sodium butyrate, 5-aza-cytidine [3] | Epigenetic modifiers that increase reprogramming efficiency |

| Culture Matrices | Matrigel, Vitronectin, Laminin-521 [7] | Synthetic or purified extracellular matrix for feeder-free culture |

| Pluripotency Media | mTeSR, StemFlex, Essential 8 [4] | Defined, xeno-free media for maintaining pluripotent state |

| Differentiation Inducers | BMP4, Activin A, CHIR99021, Retinoic Acid [4] [6] | Small molecules and growth factors directing lineage specification |

| Gene Editing Tools | CRISPR-Cas9, Base Editors [4] [5] | Precision genome engineering for creating isogenic controls |

Experimental Workflow for iPSC Generation and Characterization

A standard protocol for generating iPSCs involves the following key steps:

Somatic Cell Source Selection and Preparation: Obtain starting cells (typically dermal fibroblasts or peripheral blood mononuclear cells) and culture in appropriate media to achieve optimal density and viability [3].

Reprogramming Factor Delivery: Transduce cells with non-integrating vectors (e.g., Sendai virus or mRNA) encoding the OSKM factors. The choice of delivery system depends on the balance between efficiency and safety requirements [4] [3].

Culture and Colony Expansion: Transfer transduced cells to feeder-free conditions on defined matrices approximately 4-7 days post-transduction. Replace media with defined pluripotency-supporting medium (e.g., mTeSR). Monitor for emergence of compact, ESC-like colonies with defined borders between days 14-28 [4].

Colony Picking and Expansion: Mechanically pick or dissociate distinct iPSC colonies and transfer to new culture vessels for expansion. Clonally expanded lines should be banked at early passages [4].

Quality Control and Characterization:

- Pluripotency Marker Validation: Confirm expression of key proteins (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, SSEA-4) via immunocytochemistry and/or flow cytometry [1].

- Trilineage Differentiation Potential: Demonstrate differentiation into ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm derivatives in vitro (embryoid body formation) or in vivo (teratoma assay) [1].

- Karyotype Analysis: Perform G-banding or spectral karyotyping to ensure genomic integrity [5].

- Short Tandem Repeat (STR) Profiling: Authenticate cell line identity and confirm match to donor somatic cells [8].

- Microbiological Testing: Screen for mycoplasma and other contaminants [8].

Applications in Patient-Specific Disease Modeling

The ability to generate iPSCs from patients with genetic diseases has revolutionized biomedical research by providing unprecedented access to human-specific disease models. These models retain the patient's complete genetic background, enabling investigation of disease mechanisms and drug responses in a personalized context [9] [6].

Advanced Modeling Platforms

Two-Dimensional (2D) Models represent the foundational approach, where iPSCs are differentiated into specific cell types (e.g., neurons, cardiomyocytes) as monolayers [7]. These systems have successfully modeled monogenic disorders like Parkinson's disease and Long QT syndrome, revealing disease-specific phenotypes such as impaired mitochondrial function and electrophysiological abnormalities [7]. However, 2D models lack the tissue-level complexity and cell-cell interactions present in native organs [7].

Three-Dimensional Organoids are self-organizing structures that more accurately recapitulate tissue architecture and cellular heterogeneity [9] [7]. These complex models have been developed for brain, kidney, liver, and heart tissues, enabling the study of cell-cell interactions and tissue-level disease phenotypes not observable in 2D cultures [9] [7]. For example, brain organoids have been used to model neurodevelopmental disorders, while kidney organoids have replicated cyst formation in polycystic kidney disease [9].

Microphysiological Systems (Organ-on-a-Chip) integrate iPSC-derived tissues with microfluidic platforms to incorporate physiological cues such as fluid flow, mechanical strain, and tissue-tissue interfaces [7]. These systems enable real-time monitoring of functional parameters and have been applied to model the blood-brain barrier, cardiac function, and drug-induced organ toxicity [7].

Disease Modeling Pipeline

Integration with Gene Editing for Disease Modeling

The combination of iPSC technology with CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing has become particularly powerful for disease modeling [9] [7]. Isogenic controls—where disease-causing mutations are corrected in patient-derived iPSCs or introduced into healthy iPSCs—enable researchers to study the specific effects of a mutation without confounding genetic background effects [7]. This approach has been successfully applied to model cardiac channelopathies, neurodegenerative diseases, and cystic fibrosis, allowing precise correlation between genetic lesions and cellular phenotypes [7].

Clinical Translation and Regulatory Landscape

Current Clinical Trial Landscape

The clinical application of pluripotent stem cell-based therapies has gained significant momentum. As of December 2024, a comprehensive review identified 115 global clinical trials involving 83 distinct PSC-derived products, with over 1,200 patients dosed and more than 10¹¹ cells administered without significant class-wide safety concerns [8]. These trials primarily target three therapeutic areas:

Ophthalmology: The eye represents a leading target due to its immune-privileged status, ease of surgical access, and precise functional assessment. OpCT-001, an iPSC-derived therapy for retinal degeneration, received FDA IND clearance in 2024 [8].

Neurology: Multiple iPSC-derived neural progenitor cell therapies for Parkinson's disease, spinal cord injury, and ALS have received FDA IND clearance [8]. These off-the-shelf products aim to provide scalable cell sources for neurodegenerative conditions.

Oncology: iPSC-derived immune cells, particularly natural killer (NK) cells and CAR-T cells, are being developed as allogeneic cancer immunotherapies [8]. FT819, an off-the-shelf iPSC-derived CAR T-cell therapy for systemic lupus erythematosus, received FDA RMAT designation in 2025 [8].

Table 4: Select FDA-Authorized Stem Cell Clinical Trials (2023-2025)

| Therapy Name | Cell Type | Indication | Development Stage | Key Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fertilo | iPSC-derived ovarian support cells | Infertility | Phase III (FDA IND cleared) | First iPSC-based therapy in U.S. Phase III; supports ex vivo oocyte maturation [8] |

| OpCT-001 | iPSC-derived photoreceptor cells | Retinal degeneration | Phase I/IIa | First iPSC-based therapy for primary photoreceptor diseases [8] |

| FT819 | iPSC-derived CAR T-cells | Systemic lupus erythematosus | Phase I (RMAT designation) | Off-the-shelf allogeneic approach [8] |

| iPSC-derived NPCs | Neural progenitor cells | Parkinson's disease, SCI, ALS | Phase I (FDA IND cleared) | Multiple off-the-shelf products [8] |

| MyoPAXon | iPSC-derived muscle progenitors | Duchenne muscular dystrophy | Phase I | Allogeneic muscle progenitor cells [8] |

Regulatory Pathways and Approved Therapies

The transition from research to clinically approved therapies requires navigating rigorous regulatory pathways. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) distinguishes between Investigational New Drug (IND) authorization, which permits clinical trials, and full Biologics License Application (BLA) approval for marketing [8]. Recent FDA-approved stem cell products include:

Omisirge (omidubicel-onlv): Approved in 2023 for hematologic malignancies, this cord blood-derived hematopoietic progenitor cell product accelerates neutrophil recovery after transplantation [8].

Lyfgenia (lovotibeglogene autotemcel): Approved in 2023 for sickle cell disease, this autologous cell-based gene therapy modifies patient hematopoietic stem cells to produce anti-sickling hemoglobin [8].

Ryoncil (remestemcel-L): Approved in 2024 as the first MSC therapy for pediatric steroid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease [8].

The FDA's Regenerative Medicine Advanced Therapy (RMAT) designation provides expedited development pathways for promising therapies, reflecting the agency's commitment to advancing the field [8].

Future Perspectives and Challenges

The future of pluripotent stem cell research will be shaped by several key developments. Precision medicine integration will leverage patient-specific iPSCs to tailor drug therapies to individual genetic backgrounds, potentially revolutionizing treatment personalization [2] [6]. Advanced bioengineering approaches, including better organoid vascularization, maturation, and the creation of multi-organ systems ("body-on-a-chip"), will enhance physiological relevance [9] [7]. Immune evasion strategies, such as CRISPR-mediated deletion of HLA genes and induction of hypoimmunogenic cells, will facilitate allogeneic transplantation without immunosuppression [4].

Despite remarkable progress, significant challenges remain. Tumorigenicity risks associated with residual undifferentiated cells or genetic abnormalities necessitate stringent safety monitoring [5]. Manufacturing scalability must be addressed through automated, cost-effective Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) processes to enable widespread clinical application [9]. Functional maturity of iPSC-derived cells often remains fetal-like, requiring improved maturation protocols to accurately model adult-onset diseases [7]. Standardization and reproducibility across different laboratories and cell lines continue to present hurdles that the field must overcome through established benchmarking and quality control measures [9] [10].

As these challenges are addressed, pluripotent stem cell technologies will increasingly transform biomedical research, drug development, and clinical practice, ultimately fulfilling their potential to provide personalized regenerative therapies for a wide range of debilitating conditions.

Patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) are catalyzing a paradigm shift in biomedical research and drug discovery. By enabling the generation of patient-specific somatic cells, iPSC technology directly addresses the critical limitations of traditional animal models and primary cell cultures. This whitepaper details the three core advantages of iPSC-based platforms: (1) patient specificity for modeling genetic diseases and personalizing therapeutic interventions; (2) human relevance for superior predictive power in pharmacology and toxicology; and (3) unlimited scalability for high-throughput drug screening and regenerative medicine. We provide a technical overview of the experimental methodologies, signaling pathways, and reagent solutions that underpin these advantages, offering researchers a framework for implementing these transformative technologies.

Patient Specificity: Modeling the Individual in a Dish

The ability to derive iPSCs from any individual imbues disease models with the unique genetic and epigenetic makeup of the patient. This patient specificity is foundational for precision medicine, allowing for the study of disease mechanisms in a genetically relevant context and the tailoring of drug therapies [11].

Technical Implementation and Workflow

The core process involves reprogramming a patient's somatic cells (e.g., dermal fibroblasts or blood cells) into pluripotent stem cells, which are then differentiated into the target cell types affected by the disease.

Diagram 1: Workflow for generating patient-specific disease models from iPSCs.

Key Methodologies and Validation

Initial reprogramming often uses the Yamanaka factors (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc) delivered via non-integrating methods (e.g., Sendai virus, mRNA) to minimize genomic alteration risks [12]. The resulting iPSCs are characterized for pluripotency markers (OCT3/4, NANOG) before directed differentiation. Disease phenotypes are validated through functional assays (e.g., electrophysiology for cardiomyocytes, cytochrome P450 activity for hepatocytes) and genetic correction to confirm causality of identified variants [11] [12].

Human Relevance: Bridging the Translational Gap

Traditional drug development relies heavily on animal studies, which suffer from interspecies differences in physiology, genetics, and disease pathogenesis, contributing to a >90% failure rate in clinical trials [13]. iPSC-derived human cells offer a biologically relevant alternative.

Quantitative Superiority of Human-Relevant Models

The table below summarizes the comparative performance of traditional models versus human iPSC-based systems.

| Model Characteristic | Animal Models | Primary Human Cells | iPSC-Derived Cells |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physiological Relevance | Low (e.g., mouse heart rate: 500 bpm vs. human: 60-100 bpm) [11] | High | High |

| Genetic Diversity | Limited (inbred strains) [13] | High, but limited availability | Can capture population diversity |

| Predictive Value for Drug Toxicity | Poor (false positives/negatives) [13] | Good, but limited lifespan | High (e.g., Liver Chips outperform animals) [14] |

| Scalability for HTS | Low | Very Low | High [11] |

| Cost and Timeline | High cost, long duration [14] | High cost, limited supply | Cost-effective after initial setup |

Advanced Human-Relevant Model Systems

To enhance physiological accuracy, iPSCs are being integrated into complex in vitro systems:

- Organ-on-Chips (OoCs): Microfluidic devices lined with iPSC-derived cells that emulate tissue-tissue interfaces, mechanical forces, and vascular perfusion. For example, Liver Chips have demonstrated superior prediction of drug-induced liver injury compared to animal models [14] [13].

- 3D Organoids: Self-organizing, three-dimensional structures that recapitulate key aspects of organ development and cellular complexity, such as the presence of multiple cell types and spatial organization [15] [13].

Unlimited Scalability: Enabling High-Throughput Science

The self-renewal capacity of iPSCs provides a limitless source of specific cell types, overcoming the critical bottleneck of cell sourcing that has plagued primary cell research [11] [12].

Scalable Differentiation Protocols

Modern cardiac differentiation protocols, for instance, achieve efficiencies >90% using a chemically defined, small-molecule-directed approach in monolayer cultures, enabling mass production of cardiomyocytes [11]. The process is orchestrated by manipulating key developmental signaling pathways.

Diagram 2: Signaling pathway control in scalable cardiomyocyte differentiation.

Applications in Drug Discovery and Screening

The scalable production of human cells enables applications previously deemed impractical:

- High-Throughput Toxicity Screening: iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes are used to screen compounds for cardiotoxic effects, such as QT interval prolongation, on a large scale [11].

- Phenotypic Drug Screens: Large libraries of compounds can be tested on patient-specific disease models (e.g., for Long QT syndrome, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy) to identify novel therapeutics [11].

- Clinical Trial in a Dish: Using a diverse bank of iPSC lines, researchers can pre-test drug efficacy and safety across a genetically varied human population, potentially de-risking clinical trials [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

A successful iPSC-based research program relies on a suite of core reagents and tools, as detailed below.

| Research Reagent | Function and Application | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | Induce pluripotency in somatic cells. | Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc (OSKM) [12]. |

| Small Molecule Inducers | Direct lineage-specific differentiation by modulating key signaling pathways. | GSK-3β inhibitor (CHIR99021) for mesoderm induction; WNT inhibitors (IWR-1) for cardiac specification [11]. |

| Chemically Defined Media | Provide a controlled, reproducible environment for differentiation and maintenance. | Essential for robust, high-efficiency generation of cells like cardiomyocytes and hepatocytes [11] [12]. |

| Extracellular Matrix (ECM) | Provides the physical scaffold for 3D cell culture and organoid formation. | Matrigel or synthetic hydrogels used for organoid generation and OoC seeding [13]. |

| Characterization Antibodies | Validate pluripotency and differentiation efficiency via immunostaining or flow cytometry. | Antibodies against OCT3/4, NANOG (pluripotency); TNNT2 (cardiomyocytes) [11]. |

Overcoming Ethical and Practical Limitations of Traditional Models

Traditional preclinical models, particularly animal systems, have long been the cornerstone of biomedical research. However, a significant translational gap persists, with a high proportion of drug candidates failing in human clinical trials due to unpredicted toxicities or inefficacies not predicted by animal studies [9]. This disconnect stems from fundamental species-specific differences in genetics, immune responses, and organ physiology [9]. The field is now undergoing a paradigm shift toward patient-specific disease modeling using human stem cells, which offers unprecedented access to human-specific biology and a path to overcome both the ethical and practical limitations of traditional models.

The advent of human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) has been particularly transformative. These cells, generated by reprogramming adult somatic cells, bypass the ethical controversies associated with embryonic stem cells while providing a patient-specific pluripotent cell source [16]. This breakthrough, coupled with advances in organoid culture and genome editing, has positioned stem cell-based approaches as a cornerstone for ethical and clinically predictive research [9].

The Limitations of Traditional Animal Models

The reliance on animal models has created a bottleneck in the drug development pipeline. Their limitations can be categorized into practical and ethical concerns.

Practical and Translational Shortcomings

The primary practical limitation is the poor predictive power for human outcomes. Rodents, despite their utility, often fail to capture key aspects of human physiology and disease pathogenesis [9]. This species disconnect contributes to high dropout rates in drug development, where promising interventions fail in human clinical trials. Furthermore, immortalized cell lines (e.g., HeLa, SH-SY5Y), while easy to culture, are often derived from cancers and display unpredictable or non-physiological behaviors, making them poor models for human disease [17].

Ethical Considerations

The use of animal models raises significant welfare concerns, which are subject to increasing public scrutiny and regulatory pressure. While the "3Rs" (Replacement, Reduction, Refinement) have been a guiding principle, the ultimate goal for many researchers is the complete replacement of animal models where scientifically possible. Stem cell-based human models represent the most promising path toward achieving this goal, aligning with ethical principles of social justice and minimizing harm [18].

Stem Cell-Based Models: A Paradigm Shift

Stem cell technologies offer a revolutionary toolbox for creating human-relevant systems. The key cell types and their characteristics are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Human Stem Cell Types for Disease Modeling

| Stem Cell Type | Source | Differentiation Potential | Key Advantages | Primary Ethical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) | Reprogrammed somatic cells (e.g., skin, blood) [16] | Pluripotent | Patient-specific; avoids embryo destruction; suitable for autologous therapy [16] | Donor consent; potential misuse [16] |

| Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) | Inner cell mass of blastocysts [16] | Pluripotent | Gold standard for pluripotency; robust differentiation protocols | Destruction of human embryos [16] |

| Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | Adult tissues (e.g., bone marrow, adipose) [9] | Multipotent | Immunomodulatory effects; lower ethical concerns; readily accessible | Tissue procurement and handling affect quality [9] |

| Organoids | Self-organizing stem cells (PSCs or adult) [9] | Varies (tissue-specific) | 3D architecture; recapitulates tissue heterogeneity; models cell-cell interactions [9] | Complexity of oversight for sensitive models (e.g., neural) [18] |

Core Technological Advantages

The superiority of stem cell models is built on three pillars:

- Patient Specificity: iPSCs carry the donor's genome, including disease-associated mutations, enabling direct modeling of rare or complex genetic diseases in a human cellular context [17].

- Human Relevance: Differentiated iPSC-derived cells (e.g., neurons, cardiomyocytes) recapitulate key functional aspects of real human tissue, such as synaptic activity and contractility, providing a physiologically accurate platform for study [17].

- Scalability and Throughput: Once a differentiation protocol is established, iPSC lines can be expanded indefinitely and manufactured at a scale required for high-throughput drug screening, including in 384- or 1536-well formats [17].

Experimental Protocols for Patient-Specific Disease Modeling

This section provides a detailed methodology for establishing a patient-specific disease model using iPSCs, from somatic cell reprogramming to phenotypic analysis.

Protocol 1: Generating and Validating an iPSC-Based Disease Model

Goal: To create a patient-specific iPSC line, differentiate it into relevant target cells, and model a disease phenotype.

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Somatic Cell Source and Reprogramming:

- Obtain patient somatic cells (e.g., skin fibroblasts or peripheral blood mononuclear cells) with appropriate informed consent and ethical approval [18].

- Reprogram cells using a non-integrating method, such as Sendai virus or synthetic mRNA delivery of the Yamanaka factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC). This avoids genomic integration, a critical safety consideration.

- Culture emerging iPSC colonies on feeder layers or in defined, feeder-free conditions. Manually pick and expand clonal lines based on characteristic embryonic stem cell-like morphology.

iPSC Line Validation:

- Pluripotency Validation: Confirm the expression of key pluripotency markers (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG) via immunocytochemistry and flow cytometry. Perform in vitro trilineage differentiation (ectoderm, mesoderm, endoderm) to confirm differentiation potential.

- Genetic Integrity: Perform karyotype analysis (G-banding) or higher-resolution CNV analysis to ensure genomic stability acquired during reprogramming [9].

- Identity Confirmation: Use STR profiling to confirm the line matches the original donor.

In Vitro Disease Modeling:

- Differentiate validated iPSCs into the relevant cell type(s) using established, published protocols. For example:

- For complex tissue modeling, generate 3D organoids that self-organize to recapitulate tissue architecture and cellular heterogeneity [9]. For kidney disease, organoids carrying PKD1 or PKD2 mutations form cysts, mimicking polycystic kidney disease pathology [9].

Phenotypic and Functional Analysis:

- Characterization: Use immunostaining and single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) to validate cell types and maturity. Compare disease lines to isogenic controls or healthy lines.

- Functional Assays: Perform assays relevant to the disease, such as:

- Multi-electrode arrays (MEA) for neuronal or cardiac electrophysiology.

- Calcium imaging for neuronal or cardiomyocyte functional analysis.

- High-content imaging to quantify disease-relevant phenotypes (e.g., tau aggregation in neurons, lipid accumulation in hepatocytes) [17].

Creating Isogenic Controls (Optional but Recommended):

- Use CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing to correct the disease-causing mutation in the patient iPSC line, creating a perfect genetic control [9].

- Alternatively, introduce the disease mutation into a healthy control line. This step strengthens causal inference by isolating the effect of the specific genetic variant from the patient's background genetic variation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Reagents for iPSC-Based Disease Modeling

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Kits | CytoTune (Sendai Virus), mRNA Reprogramming Kits | Deliver transcription factors to convert somatic cells into iPSCs without genomic integration. |

| Culture Media | mTeSR1, StemFlex, Essential 8 | Maintain iPSCs in a defined, pluripotent state. |

| Differentiation Kits & Reagents | Small molecules (CHIR99021, SB431542), GMP-grade cytokines (BMP4, FGF2) | Direct lineage-specific differentiation into target cells (e.g., neurons, cardiomyocytes). |

| Characterization Antibodies | Anti-OCT4, SOX2, NANOG; Cell-type specific markers (e.g., TUJ1 for neurons, cTnT for cardiomyocytes) | Validate pluripotency and differentiation efficiency via immunocytochemistry and flow cytometry. |

| Genome Editing Tools | CRISPR-Cas9 systems (e.g., ribonucleoprotein complexes), HDR donors | Create isogenic control lines via precise gene correction or mutation. |

| Analysis Tools | Multi-electrode Arrays (MEA), High-Content Imagers, scRNA-seq kits | Perform functional and phenotypic analysis of derived cells and tissues. |

Data Presentation: Quantitative Advantages of Stem Cell Models

The quantitative benefits of stem cell models are evident across applications, from disease modeling to drug screening.

Table 3: Applications and Performance of Stem Cell-Derived Models in Drug Discovery

| Application Area | Stem Cell Model Used | Key Findings and Advantages | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiotoxicity Screening | iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes | Routinely used to screen for drug-induced arrhythmia risk; integrated into regulatory safety initiatives (CiPA). Used by pharmaceutical companies (Roche, Takeda) for preclinical cardiac profiling. [17] | [17] |

| Neurodegenerative Disease | iPSC-derived neurons from Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and ALS patients | Model disease phenotypes (tau aggregation, mitochondrial dysfunction). Support phenotypic screens identifying compounds that rescue neuronal function in vitro. [17] | [17] |

| Metabolic Disease | Hepatocyte-like cells from iPSCs of Familial Hypercholesterolemia patients | Revealed drug repurposing opportunity: cardiac glycosides reduced ApoB secretion. Provided a human-relevant system for testing lipid-lowering therapies. [17] | [17] |

| Kidney Disease | Kidney organoids with PKD1 or PKD2 mutations | Displayed cyst formation reminiscent of patient pathology, providing a robust system for mechanistic studies and therapeutic screening. [9] | [9] |

Addressing Remaining Challenges and Future Directions

Despite the promise, the field must overcome several hurdles to fully realize its potential. Key challenges and developing solutions are outlined below.

- Challenge: Functional Immaturity. iPSC-derived cells often exhibit a fetal-like gene expression profile and electrophysiological activity, limiting their ability to model late-onset diseases [9] [17].

Solution: Advanced maturation strategies are under development, including prolonged culture, biomechanical stimulation, electrical pacing for cardiomyocytes, co-culture with supporting cell types, and the introduction of vascularization to improve nutrient exchange and mimic the in vivo environment more closely [9].

Challenge: Lack of Standardization. Differentiation protocols vary significantly between laboratories, leading to inconsistent results and limiting reproducibility [9].

Solution: The field is moving toward harmonized quality standards. This includes benchmarking efforts using high-dimensional molecular profiling (e.g., scRNA-seq) and the use of commercial, QC-verified cell batches to improve cross-study comparability [9] [17].

Challenge: Scalability and Manufacturing. Translating laboratory protocols into robust, cost-effective, and cGMP-compliant production systems remains difficult [9].

Solution: Implementation of automation, closed culture systems, and high-throughput bioprocessing in bioreactors is key to bringing down costs and ensuring reproducible, large-scale production of cells for therapies and screening [9] [17].

Challenge: Evolving Ethical Oversight. As models increase in complexity (e.g., stem cell-based embryo models - SCBEMs, neural organoids), new ethical questions emerge [18].

- Solution: Adherence to updated international guidelines, such as those from the International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR). These guidelines provide frameworks for oversight, mandate a clear scientific rationale and defined endpoint for research, and prohibit the culture of SCBEMs to the point of potential viability [18].

The adoption of patient-specific stem cell models marks a critical evolution in biomedical research, directly addressing the ethical and practical limitations of traditional animal models. By providing a human-relevant, scalable, and genetically defined platform, iPSCs and organoids are bridging the long-standing translational gap in drug discovery. While challenges in standardization and functional maturation persist, they are being actively addressed through bioengineering and international collaboration. As the field moves forward, guided by rigorous science and thoughtful ethics, these technologies promise to accelerate the development of safer, more effective therapies for a wide range of debilitating human diseases.

Stem cell research has fundamentally transformed the landscape of biomedical science, providing unprecedented tools for modeling human diseases and developing regenerative therapies. This technical guide examines the current state and methodologies of patient-specific disease modeling across three key therapeutic areas: cardiovascular, neurological, and metabolic disorders. The advent of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) has been particularly revolutionary, enabling the generation of patient-specific cellular models that recapitulate disease phenotypes in vitro. These models serve as powerful platforms for deciphering disease mechanisms, screening therapeutic compounds, and developing personalized treatment approaches. While significant progress has been made, challenges remain in achieving full cellular maturation, standardization of protocols, and clinical translation. This document provides researchers with a comprehensive technical resource covering experimental protocols, key reagents, and analytical frameworks for advancing stem cell-based disease modeling and therapeutic development.

Patient-specific disease modeling using stem cells represents a paradigm shift in biomedical research, addressing critical limitations of traditional animal models. The ability to generate human iPSCs from somatic cells through genetic reprogramming has created unprecedented opportunities to study human diseases in genetically relevant human cellular systems [9]. These models more accurately reflect human pathophysiology and species-specific biology, thereby enhancing the predictive validity of preclinical research [9].

The fundamental workflow involves reprogramming patient somatic cells (typically dermal fibroblasts or blood cells) to pluripotency, differentiating these iPSCs into disease-relevant cell types, and utilizing the resulting cellular models for mechanistic studies or drug screening. The integration of CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing allows for creation of isogenic control lines, strengthening causal inference between genetic variants and disease phenotypes [9]. For neurological disorders, stem cell models have enabled researchers to "reconstitute events of human brain development that occur after birth," providing unprecedented access to previously inaccessible developmental processes [19].

Cardiovascular Disease Modeling

Current Landscape and Challenges

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) remain the leading cause of death globally, accounting for approximately 18.6 million deaths annually [20]. Myocardial infarction (MI) and atherosclerosis represent particularly devastating manifestations, with conventional treatments unable to fully regenerate damaged myocardial or vascular tissues [20]. The adult mammalian heart exhibits very limited regenerative capacity, making stem cell-based approaches particularly promising for cardiac regeneration [21].

Stem Cell Platforms and Methodologies

Multiple stem cell types are being investigated for cardiovascular disease modeling and therapy:

Table: Stem Cell Types for Cardiovascular Applications

| Stem Cell Type | Sources | Key Advantages | Major Limitations | Primary Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | Bone marrow, adipose tissue, umbilical cord [20] | Strong immunomodulatory capacity; abundant paracrine function [20] | Low survival post-transplantation (<10%); functional heterogeneity [20] | Paracrine effects; immunomodulation; homing [20] |

| Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) | Reprogrammed somatic cells [20] | Patient-specific; differentiation potential of embryonic stem cells [20] | Tumorigenic risk; residual epigenetic memory [20] | Direct differentiation; tissue replacement [20] |

| Cardiac Stem Cells (CSCs) | Adult heart [20] | Tissue-specific; can be transplanted directly to damaged heart [20] | Limited studies; mechanisms not fully elucidated [20] | Exosome secretion; anti-apoptosis; angiogenesis [20] |

| Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) | Inner cell mass of blastocyst [20] | High differentiation efficiency (70-85%) [20] | Ethical concerns; tumorigenic risk; immune rejection [20] | Direct differentiation [20] |

Key Experimental Protocols

iPSC-Derived Cardiomyocyte Differentiation

The directed differentiation of iPSCs into cardiomyocytes has been optimized using stage-specific signaling pathway modulation:

- Mesoderm Induction (Days 0-3): Culture iPSCs in RPMI/B27 medium supplemented with 6-8 µM CHIR99021 (GSK-3β inhibitor) to activate Wnt signaling [20].

- Cardiac Mesoderm Specification (Days 3-5): Replace medium with RPMI/B27 containing 2-5 µM IWP2 (Wnt inhibitor) to suppress Wnt signaling and promote cardiac commitment.

- Cardiomyocyte Maturation (Days 5-30+): Maintain cells in RPMI/B27 with occasional metabolic selection (lactate-containing media) to enrich for cardiomyocytes, achieving up to 95% purity [20].

Cardiovascular Organoid Generation

Three-dimensional cardiovascular organoids provide more physiologically relevant models for disease modeling:

- Aggregation Phase: Harvest iPSC-derived cardiac progenitors and aggregate in U-bottom plates via centrifugation (500 × g, 3 min).

- Organoid Maturation: Culture in suspension with rotational orbital shaking (60-80 rpm) for 30-60 days with defined maturation factors [9].

- Functional Assessment: Evaluate contractile function via video-based analysis, electrophysiology by microelectrode array, and structure by immunostaining for cardiac troponins, α-actinin, and connexin-43.

Technical Workflow: Cardiovascular Disease Modeling

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for creating patient-specific cardiovascular disease models using stem cells:

Neurological Disease Modeling

Current Landscape and Challenges

Neurological disorders represent a diverse set of conditions with limited treatment options and complex underlying pathophysiology. Stem cell models have emerged as essential tools for investigating disease mechanisms in human-relevant systems, particularly for disorders affecting the central nervous system [19] [22].

Advanced Modeling Platforms

Cerebral Organoids and Assembloids

Three-dimensional models have revolutionized neurological disease modeling:

- Extended Maturation Timelines: Unlike traditional 2D cultures, 3D assembloid models require extended culture periods (up to 390 days) to recapitulate postnatal developmental processes [19].

- Chain Migration of Interneurons: Advanced models demonstrate that "newly born migratory interneurons arrange themselves into connected chains that are surrounded by astrocytes," essentially recapitulating early postnatal migration patterns [19].

- Cell Biological Analysis: These models enable genetic and cell biological analysis of human-specific developmental processes previously only observable in postmortem tissue [19].

Disease-Specific Modeling Approaches

Table: Neurological Disorder Modeling Strategies

| Disorder | Stem Cell Approach | Key Phenotypes Modeled | Therapeutic Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parkinson's Disease | iPSC-derived dopaminergic neurons [22] | Loss of dopaminergic neurons; motor deficits | Cell replacement; neuroprotection via BDNF/GDNF secretion [22] |

| Multiple Sclerosis | iPSC-derived oligodendrocytes [22] | Demyelination; immune activation | Immunomodulation; remyelination promotion [22] |

| Alzheimer's Disease | iPSC-derived cortical neurons [22] | Amyloid-beta accumulation; tau pathology; cognitive decline | Reduction of amyloid plaques; enhanced neurogenesis [22] |

| Spinal Cord Injury | Neural stem cell transplantation [22] | Axonal damage; glial scar formation | Axon regeneration; glial scar modulation via MMP secretion [22] |

| Schizophrenia | Village editing in iPSC-derived neurons [19] | Transcriptional changes influenced by genetic background | NRXN1 knockout models across donors with varying polygenic risk [19] |

Key Experimental Protocols

Dorsal-Ventral Forebrain Assembloid Generation

This protocol models interneuron migration, critical for understanding neurological disorders:

- Dorsal Organoid Differentiation: Pattern iPSCs toward cortical fates using dual SMAD inhibition (LDN193189, SB431542) and Wnt activation (CHIR99021).

- Ventral Organoid Differentiation: Generate medial ganglionic eminence identities using SHH pathway activation (SAG, Purmorphamine).

- Assemblage and Maturation: Fuse dorsal and ventral organoids at day 120 and maintain for extended culture (200+ days) to observe chain migration of interneurons [19].

- Analysis: Employ time-lapse imaging, single-cell spatial transcriptomics, and mathematical modeling to quantify migration dynamics.

DRG Organoid Modeling for Pain Disorders

For Hereditary Sensory and Autonomic Neuropathy Type IV (HSAN IV):

- iPSC Differentiation: Generate dorsal root ganglion (DRG) organoids from patient-specific iPSCs carrying NTRK1 mutations.

- Isogenic Control Creation: Correct patient mutations using CRISPR/Cas9 to establish genetically matched controls.

- Phenotypic Analysis: Assess neuronal-glial differentiation balance, focusing on ISLET+/BRN3A+ sensory neuron reduction and premature gliogenesis marked by FABP7 upregulation [19].

Technical Workflow: Neurological Disease Modeling

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for creating sophisticated neural models using stem cell technologies:

Metabolic Disease Modeling

Current Landscape and Challenges

Metabolic disorders, including metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) and diabetes, represent growing global health challenges. Stem cell-derived somatic cells offer promising avenues for both disease modeling and cell replacement therapies [23].

Key Cell Types and Applications

- Hepatocyte-like Cells (HLCs): iPSC-derived HLCs model liver-specific metabolic functions and pathologies, including lipid accumulation and inflammatory responses characteristic of MASLD [23].

- Pancreatic β-like Cells: Glucose-responsive insulin-producing cells generated from stem cells hold potential for diabetes treatment, though full functional maturation remains challenging [23].

- Disease Modeling Applications: These cell types enable investigation of disease mechanisms and screening for therapeutic compounds that modulate metabolic pathways [23].

Experimental Challenges and Solutions

The field continues to address significant technical hurdles:

- Functional Maturation: Stem cell-derived hepatocyte-like and β-cells often exhibit fetal-like characteristics rather than fully mature adult phenotypes [23].

- Protocol Standardization: Differentiation protocols vary significantly between laboratories, complicating comparison of results [9].

- Metabolic Function: Achieving full metabolic capacity comparable to primary cells remains challenging, with current models showing reduced cytochrome P450 activity in HLCs and suboptimal glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in β-cells [23].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Stem Cell Disease Modeling

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC [20] | iPSC generation | Somatic cell reprogramming to pluripotency |

| Gene Editing Tools | CRISPR/Cas9 systems [9] | Isogenic control creation | Precise genetic modification |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors/Activators | CHIR99021 (Wnt activator), IWP2 (Wnt inhibitor), LDN193189 (BMP inhibitor) [20] | Directed differentiation | Lineage specification |

| Extracellular Matrix | Matrigel, laminin-521, synthetic hydrogels [20] | 3D culture systems | Structural support for organoids |

| Characterization Antibodies | CD73, CD90, CD105 (MSC markers); TRA-1-60 (pluripotency); cardiac troponins [24] | Cell type validation | Lineage confirmation |

| Secreted Factor Assays | VEGF, HGF, FGF ELISA kits [20] | Paracrine effect analysis | Quantification of secretory profiles |

| Functional Assay Kits | Microelectrode arrays, calcium imaging dyes, Seahorse metabolic kits | Physiological assessment | Functional characterization |

Technical Challenges and Future Directions

Current Limitations

Despite significant advances, stem cell disease modeling faces several persistent challenges:

- Cellular Immaturity: Stem cell-derived tissues frequently exhibit fetal-like characteristics rather than adult phenotypes, limiting their utility for modeling late-onset diseases [9].

- Protocol Variability: Lack of standardization in differentiation protocols across laboratories compromises reproducibility and comparability [9].

- Tumorigenic Risk: Residual undifferentiated pluripotent cells in therapeutic products pose potential safety concerns [20].

- Immune Compatibility: Even autologous iPSC derivatives can trigger immune responses under certain conditions [9].

- Scalability: Current manufacturing workflows are often labor-intensive and difficult to scale for widespread clinical application [9].

Innovative Solutions

The field is rapidly developing solutions to address these challenges:

- Village Editing: "CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing in a cell village format" enables parallel analysis of genetic variants across multiple donor backgrounds, revealing how genetic context influences phenotype [19].

- Lysosomal Reprogramming: Targeting lysosomal dysfunction can reverse aging in blood stem cells, with potential applications for improving stem cell function in age-related diseases [25].

- Bioengineering Approaches: Smart hydrogel scaffolds and 3D bioprinting technologies improve stem cell survival and enable construction of complex tissue architectures [20].

- Machine Learning-Assisted Differentiation: EpiCRISPR technology reduces inter-batch variation in gene expression to 6.4%, significantly improving differentiation consistency [20].

Signaling Pathways in Stem Cell-Based Therapy

The following diagram summarizes the key molecular mechanisms through which stem cells exert their therapeutic effects:

Patient-specific disease modeling using stem cells has emerged as a transformative approach across cardiovascular, neurological, and metabolic disorders. The integration of iPSC technology with advanced gene editing, 3D culture systems, and multi-omics analyses has created unprecedented opportunities for understanding disease mechanisms and developing targeted therapies. While challenges remain in achieving full cellular maturation, protocol standardization, and clinical translation, ongoing innovations in bioengineering, computational biology, and manufacturing processes continue to advance the field. As these technologies mature, stem cell-based disease models will play an increasingly central role in drug discovery, personalized medicine, and regenerative therapies, ultimately enabling more effective and precise interventions for complex human diseases.

The Shift from Animal Models to Human-Relevant Systems

The field of biomedical research has long depended on animal models to investigate disease mechanisms and test therapeutic candidates. However, the translational gap between preclinical models and human clinical trials has become increasingly evident, with a significant proportion of drug candidates failing due to unpredicted toxicities or inefficacies in humans [9]. This disconnect stems from fundamental species-specific differences in genetics, immune responses, and organ physiology that limit the predictive power of traditional animal models [9]. In response to these challenges, human stem cell research has undergone a remarkable transformation over the last two decades, transitioning from pioneering discoveries in developmental biology to clinical applications that now shape the future of regenerative medicine and drug development [9].

The advent of human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), followed by advanced organoid culture systems and genome editing technologies, has provided unprecedented access to patient-specific and pluripotent cell sources capable of differentiating into virtually any cell type [9]. These technological advances have positioned stem cell-based approaches as a cornerstone for disease modeling, drug development, and therapeutic innovation, offering a transformative opportunity to improve translational fidelity, increase therapeutic success rates, and reduce the reliance on animal models [9]. This whitepaper examines the scientific foundations, current applications, and methodological considerations underlying this paradigm shift toward human-relevant systems in biomedical research.

The Limitations of Traditional Animal Models

Traditional animal models, particularly rodents, have been the mainstay of biomedical research for decades. However, their limitations in predicting human responses have become increasingly apparent throughout the drug development pipeline. The fundamental biological differences between species contribute to high dropout rates for drug candidates, as promising interventions frequently fail in human clinical trials despite showing efficacy in animal models [9].

The disconnect between animal models and human biology manifests in several critical areas:

- Genetic and metabolic differences that alter drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics

- Divergent immune system responses to pathogens and therapeutic interventions

- Structural and functional variations in organ systems and tissue architecture

- Species-specific disease mechanisms that do not fully recapitulate human pathology

These limitations are particularly problematic for complex human-specific diseases, including many neurological disorders, autoimmune conditions, and metabolic diseases, where animal models often fail to capture essential aspects of disease pathophysiology and progression [9]. The inability of traditional models to accurately predict human responses has driven the search for more relevant experimental systems that better mirror human biology.

Human Stem Cell-Based Model Systems: Technological Foundations

Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs)

The development of human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) represents a watershed moment in biomedical research. iPSCs are generated by reprogramming adult somatic cells to a pluripotent state, capable of differentiating into virtually any cell type in the human body [9]. This breakthrough technology provides three distinct advantages that make it a powerful tool across research and early-stage drug development [17]:

Table 1: Key Advantages of iPSC-Based Disease Models

| Advantage | Description | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Patient Specificity | iPSCs carry the donor's genome, including disease-associated mutations | Direct modeling of rare or complex genetic diseases in human cells [17] |

| Human Relevance | Differentiated cells recapitulate key functional aspects of real tissue | Study of synaptic activity, contractility, metabolic capacity in human context [17] |

| Scalability | Indefinite expansion potential with locked-in differentiation protocols | Manufacturing at scale required for high-throughput screening [17] |

iPSCs have moved from niche innovation to mainstream application, becoming a go-to tool for building more predictive, human-relevant assays in drug discovery workflows [17]. Their ability to maintain the donor's genotype and demonstrate complex functional behaviors that immortalized cell lines cannot replicate makes them particularly valuable for disease modeling and drug screening [17].

Organoid and Assembloid Technologies

The ability to generate organoids—self-organizing, three-dimensional tissue structures derived from stem cells—has been especially transformative for disease modeling [9]. Organoids recapitulate aspects of tissue architecture and function, and their emergence has opened new frontiers in disease modeling for neurological disorders, congenital heart disease, polycystic kidney disease, and cancer [9].

Complementing organoid technology, assembloids represent a more advanced approach that combines multiple organoid types or tissue lineages. These complex systems have allowed the modeling of inter-organ interactions, such as brain–muscle or brain–vascular connectivity, providing unprecedented opportunities to study human physiology and disease in a more integrated manner [9].

When provided with the proper 3D scaffold and biochemical factors, stem cells can differentiate and self-organize to form tissue-specific organoids like the optic cup, brain, intestine, liver, and kidney [26]. The homeostasis of these tissues is maintained through self-renewal and differentiation mechanisms similar to those observed in vivo, making organoids particularly valuable for studying tissue development, disease mechanisms, and drug responses [26].

Genome Editing Technologies

The combination of stem cell technologies with CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing has revolutionized disease modeling by allowing for precise manipulation of disease-associated mutations in human cells [9]. This approach enables researchers to create isogenic control lines that differ only at specific disease-relevant loci, strengthening causal inference in disease modeling studies [9].

Genome editing has already been successfully used to model monogenic conditions such as cystic fibrosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and Duchenne muscular dystrophy, providing robust platforms for mechanistic studies and therapeutic screening [9]. The precision of these editing technologies, combined with the human relevance of iPSC-derived models, exemplifies the maturation of human stem cell platforms into predictive disease models that bridge the gap between traditional cell culture and clinical research.

Applications in Disease Modeling and Drug Development

Neurodegenerative Disorders

iPSC-based models have shown particular promise in modeling neurodegenerative diseases, which have been notoriously difficult to recapitulate in animal models. iPSC-derived neurons from patients with Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and ALS are used to model disease phenotypes like tau aggregation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and motor neuron degeneration [17]. These cultures support phenotypic screens that have identified compounds capable of rescuing neuronal function in vitro [17].

For Parkinson's disease specifically, recent advances have included the generation of dopaminergic neurons from unconventional sources such as ovarian cortical-derived progenitors, which demonstrate electrophysiological activity and point to new avenues for autologous therapies [9]. Additionally, MSC-based approaches have shown therapeutic potential for spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA), with preclinical studies suggesting that MSCs can enhance Purkinje cell survival and motor coordination through immunomodulatory and neurotrophic effects [9].

Cardiovascular Disease and Cardiotoxicity

iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes have become a standard tool in cardiac safety screening and are gaining regulatory acceptance. These cells are now used routinely to screen for drug-induced arrhythmia risk and have been integrated into regulatory safety initiatives like CiPA (Comprehensive in Vitro Proarrhythmia Assay) [17]. Companies including Roche and Takeda utilize iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes for preclinical cardiac profiling, reflecting the growing acceptance of these human-relevant systems in pharmaceutical development [17].

Cardiovascular organoids derived from pluripotent stem cells provide valuable insights into cardiac development, congenital heart disease, and drug-induced cardiotoxicity [9]. These models enable the study of cardiomyocyte maturation and tissue-level electrophysiology in a human-relevant context, though challenges remain in achieving full vascularization and structural maturation comparable to adult heart tissue [9].

Metabolic and Renal Diseases

In metabolic disease research, hepatocyte-like cells derived from iPSCs have been used to model conditions such as familial hypercholesterolemia and test potential lipid-lowering therapies [17]. In one notable example, an iPSC-based drug screen revealed a drug repurposing opportunity when cardiac glycosides were found to reduce ApoB secretion [17].

Kidney organoids have demonstrated significant utility for modeling renal diseases, particularly autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) [9]. Organoids carrying PKD1 or PKD2 mutations display cyst formation reminiscent of patient pathology, providing a robust system for mechanistic studies and therapeutic screening for a condition with limited treatment options [9].

Table 2: Stem Cell Applications Across Disease Areas

| Disease Area | Stem Cell Model | Key Applications | Notable Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neurodegeneration | iPSC-derived neurons, MSC therapies | Disease modeling, phenotypic screening, cell therapy | Compounds rescuing neuronal function; Enhanced Purkinje cell survival with MSCs [9] [17] |

| Cardiovascular | iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes, cardiovascular organoids | Cardiotoxicity screening, disease modeling, developmental studies | Integration into CiPA safety initiative; Identification of arrhythmia risks [9] [17] |

| Metabolic | iPSC-derived hepatocyte-like cells | Disease modeling, drug screening | Cardiac glycosides reduce ApoB secretion [17] |

| Renal | Kidney organoids | Disease modeling, mechanism studies | Cyst formation in ADPKD models [9] |

| Reproductive | Ovarian stem cells (OSCs) | Infertility treatment | Differentiation into oocyte-like cells for premature ovarian failure [9] |

High-Throughput Screening and Drug Discovery

iPSC-derived cells are not just biologically relevant—they are also compatible with high-throughput screening methodologies essential for modern drug discovery. These cells can be plated in 384- or 1536-well formats, imaged automatically, and used to extract rich phenotypic data at scale [17].

iPSC-based models are increasingly being used in industrial phenotypic screens to identify new drugs, predict toxicity, and uncover mechanisms of action. Using high-content imaging, researchers can quantify changes in cell morphology, protein localization, or organelle health across thousands of wells. When combined with machine learning approaches, this data can be analyzed in bulk to identify compounds that reverse disease features, even when the molecular target isn't known beforehand [17].

This compatibility with automated screening platforms makes iPSC technology particularly valuable for early drug discovery, where the ability to test large compound libraries against human-relevant disease models can significantly improve the efficiency of identifying promising therapeutic candidates.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

iPSC Differentiation Workflows

The successful implementation of stem cell-based disease models requires robust and reproducible differentiation protocols. While specific methods vary by cell type and application, general principles underlie most iPSC differentiation workflows:

Cardiomyocyte Differentiation Protocol

- iPSC Maintenance: Culture iPSCs in essential 8 medium on vitronectin-coated plates until 80-85% confluent

- Mesoderm Induction: Treat with CHIR99021 (GSK-3β inhibitor) in RPMI/B27-insulin medium for 24-48 hours

- Cardiac Specification: Switch to RPMI/B27-insulin medium without CHIR99021 for 48 hours

- Metabolic Selection: Replace medium with RPMI/B27-complete (containing insulin) for 10-15 days with regular feeding

- Functional Validation: Assess beating behavior, cardiac troponin expression, and electrophysiological properties

Neuronal Differentiation Protocol

- Neural Induction: Treat iPSCs with dual SMAD signaling inhibitors (dorsomorphin and SB431542) in neural induction medium for 10-14 days

- Neural Progenitor Expansion: Passage neural rosettes and expand in neural expansion medium containing FGF2 and EGF

- Terminal Differentiation: Withdraw mitogens and culture in neuronal differentiation medium containing BDNF, GDNF, and cAMP

- Functional Maturation: Maintain cultures for 4-8 weeks with regular feeding, assess synaptic activity and neuronal marker expression

These protocols highlight the importance of precise temporal control of signaling pathways and growth factors to direct stem cell differentiation toward specific lineages. However, variability between laboratories remains a challenge, underscoring the need for standardized approaches and rigorous quality control [9].

Organoid Generation and Maintenance

The generation of complex 3D organoids requires additional considerations beyond 2D differentiation protocols:

Essential Components for Organoid Culture

- Extracellular Matrix: Matrigel or synthetic hydrogels to provide 3D scaffold

- Patterning Factors: Small molecules and growth factors to establish regional identity

- Maturation Factors: Hormones, nutrients, and mechanical stimuli to promote functional maturation

Recent advances have incorporated bioengineering strategies such as microfluidic platforms, electrical stimulation, and mechanical loading to improve the physiological fidelity of organoid models [9]. These approaches address limitations in vascularization and structural maturation that often constrain the utility of stem cell-derived tissues [9].

Diagram 1: Stem Cell Disease Modeling Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of stem cell-based disease models requires careful selection of research reagents and materials. The following table details essential components and their functions in establishing robust experimental systems:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Stem Cell Disease Modeling

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | OSKM factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC) | Reprogram somatic cells to pluripotency | Integration-free methods preferred for clinical applications |

| Extracellular Matrices | Matrigel, vitronectin, laminin, synthetic hydrogels | Provide structural support and biochemical cues | Batch variability; defined synthetic alternatives reducing variability |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors/Activators | CHIR99021 (GSK-3β inhibitor), SB431542 (TGF-β inhibitor), dorsomorphin | Direct differentiation by modulating signaling pathways | Concentration and timing critical for specific lineage commitment |

| Growth Factors & Cytokines | FGF2, EGF, BDNF, GDNF, BMPs, WNTs | Promote survival, proliferation, and differentiation | Cost considerations for large-scale applications; recombinant human proteins preferred |

| Culture Media Formulations | mTeSR, Essential 8, neural induction medium, cardiac differentiation medium | Provide nutrients and maintain specific cell states | Xeno-free formulations important for clinical translation |

| Genome Editing Tools | CRISPR-Cas9 systems, base editors, prime editors | Introduce disease-associated mutations or correct genetic defects | Off-target effects monitoring; isogenic control generation |

| Characterization Tools | Flow cytometry antibodies, PCR primers, electrophysiology systems | Validate cell identity, purity, and function | Multimodal characterization recommended for comprehensive assessment |

Current Challenges and Future Directions

Technical and Standardization Challenges

Despite the promising advances in human stem cell-based models, several significant challenges remain that must be addressed for the field to realize its full potential:

Standardization and Reproducibility The lack of standardization in differentiation protocols represents a major hurdle. Even for the same lineage, methods can vary significantly between laboratories, leading to inconsistent results and limiting reproducibility [9]. Recent benchmarking efforts using high-dimensional molecular profiling have highlighted the extent of this variability and underscored the need for harmonized quality standards across laboratories [9].

Functional Maturation Stem cell-derived systems frequently display developmental immaturity, maintaining fetal-like gene expression profiles, electrophysiological activity, or metabolic states [9]. This immaturity affects both their structural and functional fidelity and their ability to respond to stimuli in a manner comparable to adult tissues. Addressing this limitation requires the development of advanced maturation strategies, including prolonged culture, biomechanical stimulation, vascularization, and co-culture with supporting cell types that more closely approximate the adult in vivo environment [9].

Scalability and Manufacturing Translating stem cell technologies into widely available research tools and clinical therapies requires robust, cost-effective, and cGMP-compliant production systems [9]. Current workflows are often labor-intensive and difficult to scale, raising concerns about feasibility for widespread use [9]. Advances in automation, closed culture systems, and high-throughput bioprocessing will be critical to overcoming these barriers.

Diagram 2: Challenges and Solutions in Stem Cell Models

Safety and Ethical Considerations

Safety remains a central concern for the clinical translation of stem cell-based technologies. The risks of genomic instability, acquired during prolonged culture or as a consequence of reprogramming, pose significant barriers to clinical application [9]. Furthermore, while iPSCs were initially thought to be immunologically inert, subsequent studies revealed that even autologous iPSC derivatives can trigger immune responses under certain conditions [9]. Addressing these safety issues requires stringent quality control and regulatory oversight, including comprehensive potency assays, long-term biodistribution monitoring of transplanted cells, and careful assessment of tumorigenic potential.

Ethical considerations also remain at the forefront of stem cell research. The field continues to navigate questions related to the use of embryonic stem cells, gene editing, and the commercialization of stem cell therapies [9]. The International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR) has established updated guidelines to address these challenges, promoting an ethical, practical, and sustainable approach to stem cell research and the development of cell therapies [18]. These guidelines emphasize fundamental principles including integrity of the research enterprise, primacy of patient welfare, respect for research subjects, transparency, and social justice [18].

Future Perspectives

Looking forward, several key developments are poised to advance the field of human stem cell-based disease modeling:

Multi-system Integration The development of more sophisticated assembloid systems that combine multiple tissue types will enable researchers to study inter-organ communication and systemic disease processes in ways that have not been previously possible. These integrated approaches may help bridge the gap between isolated tissue models and whole-organism physiology.

Advanced Analytics and AI The integration of high-content screening data with machine learning approaches will enhance the predictive power of stem cell-based assays. These computational methods can identify subtle patterns in complex datasets that may not be apparent through traditional analysis, potentially revealing new disease mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities.

Personalized Medicine Applications As protocols become more standardized and efficient, the use of patient-specific iPSCs for personalized drug screening may become clinically feasible. This approach could help identify optimal treatment strategies for individual patients, particularly for complex or rare genetic disorders where response to conventional therapies is variable.

The continued evolution of human stem cell-based models represents a paradigm shift in biomedical research, offering unprecedented opportunities to study human disease in relevant systems and accelerate the development of safer, more effective therapies. By addressing current challenges through collaborative science and technological innovation, these approaches promise to transform both basic research and clinical medicine in the coming years.

From Cells to Complex Systems: Methodologies and Translational Applications

The advent of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology represents a paradigm shift in biomedical research, creating unprecedented opportunities for patient-specific disease modeling. Since the seminal discovery by Takahashi and Yamanaka that somatic cells could be reprogrammed to a pluripotent state using defined factors, the field has evolved rapidly with significant refinements in technique, safety, and efficiency [3] [1]. This technology now serves as a cornerstone for generating patient-specific cellular models that recapitulate disease pathology in vitro, enabling mechanistic studies of pathogenesis and high-throughput drug screening without the ethical concerns associated with embryonic stem cells [27] [5]. The ability to derive iPSCs from individuals with genetic disorders has transformed our approach to studying human diseases, particularly for neurological conditions, cardiovascular disorders, and rare genetic syndromes where animal models often fail to fully capture human pathophysiology [28] [17]. This technical guide comprehensively outlines the current methodologies, molecular mechanisms, and applications of iPSC derivation, with a specific focus on their utility in disease modeling platforms that support both basic research and therapeutic development.

Historical Foundations and Conceptual Framework

The conceptual foundation for cellular reprogramming was established through decades of pioneering research that challenged the dogma of irreversible cell fate determination. In 1962, John Gurdon demonstrated that the nucleus from a differentiated somatic cell could be reprogrammed to a totipotent state when transferred into an enucleated egg, leading to the generation of cloned tadpoles [29] [1]. This seminal work in somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) provided the first experimental evidence that the genome of differentiated cells retains the information necessary to generate an entire organism, and that factors in the oocyte cytoplasm could reverse epigenetic modifications to restore developmental potential.