Source Matters: A Comparative Analysis of Mesenchymal Stem Cell Tissue Origins for Targeted Clinical Applications

The therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) is widely recognized, but their clinical translation is complicated by significant functional heterogeneity linked to tissue origin.

Source Matters: A Comparative Analysis of Mesenchymal Stem Cell Tissue Origins for Targeted Clinical Applications

Abstract

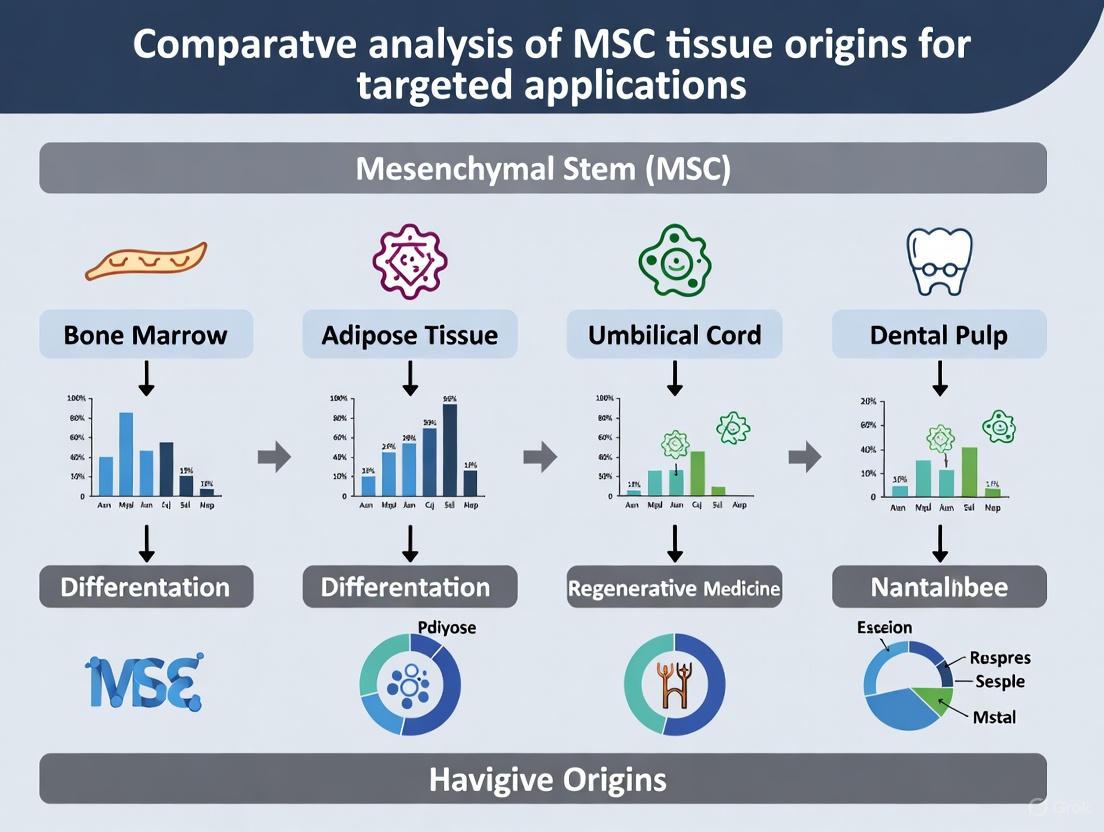

The therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) is widely recognized, but their clinical translation is complicated by significant functional heterogeneity linked to tissue origin. This review provides a comparative analysis of MSCs derived from key sources—including bone marrow, adipose tissue, dental pulp, and umbilical cord—for researchers and drug development professionals. We synthesize foundational biology, methodological protocols, and troubleshooting strategies, emphasizing how intrinsic properties like differentiation potential, immunomodulatory capacity, and secretome profiles are dictated by ontogeny. By validating these differences through direct comparative studies and clinical trial data, this article establishes a strategic framework for selecting the optimal MSC source for specific therapeutic applications, from autoimmune diseases and orthopedic injuries to novel cell-free therapies.

Unraveling MSC Heterogeneity: Developmental Origins and Native Identities

The field of mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC) research is undergoing a significant paradigm shift, moving from a traditional focus on their stem cell characteristics toward a more nuanced understanding of their stromal and immunomodulatory functions. This evolution is reflected in recent nomenclature updates from the International Society for Cell & Gene Therapy (ISCT), which now formally recommends the term "Mesenchymal Stromal Cells" instead of "Mesenchymal Stem Cells" for the majority of clinical applications [1] [2]. This terminological refinement is not merely semantic but represents a fundamental recalibration of the scientific community's understanding of how these cells function therapeutically. The shift acknowledges that the primary mechanism of action for MSCs in most clinical settings is not long-term engraftment and differentiation but rather sophisticated paracrine signaling and immunomodulation [2] [3].

This reframing has profound implications for how researchers characterize MSCs, design potency assays, and develop cell-based therapeutics. The traditional "stem cell" narrative, which emphasized differentiation potential and tissue regeneration, is being supplemented—and in some cases supplanted—by a view of MSCs as complex immunomodulatory and trophic mediators [2]. This article examines the ongoing nomenclature debate, details the updated ISCT criteria, and explores how a more precise understanding of MSC biology is driving a more targeted approach to selecting tissue sources for specific therapeutic applications.

The Nomenclature Debate: From "Stem" to "Stromal"

Historical Context and Rationale for Change

The journey of MSC terminology began with the initial discovery of these cells in the bone marrow and the subsequent coining of the term "Mesenchymal Stem Cells" by Arnold Caplan in 1991 [4] [3]. The original classification was heavily predicated on the in vitro observations of trilineage differentiation potential (adirogenic, chondrogenic, and osteogenic) and their capacity to adhere to plastic surfaces [4]. However, as in vivo data accumulated from clinical trials, a disconnect emerged between the "stem" cell nomenclature and the observed biological effects.

Converging evidence from clinical applications, particularly in immune-mediated diseases like graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), Crohn's disease, and autoimmune disorders, consistently demonstrated that the therapeutic benefits were arising primarily from paracrine effects and immunomodulation rather than lineage-driven tissue regeneration [2]. Transplanted MSCs were found to engage with host immune cells—suppressing effector T-cell activation, expanding regulatory T cells (Tregs), and reprogramming myeloid cells toward inflammation-resolving phenotypes—through the release of bioactive molecules and extracellular vesicles [2]. This mechanistic understanding, supported by the fact that engraftment of administered MSCs is often low and transient, highlighted a misalignment between the historical name and the actual primary function [3].

The ISCT Position: A Mechanism-Aligned Terminology

In 2019, and more forcefully in 2025, the ISCT Mesenchymal Stromal Cell committee released position statements addressing this nomenclature issue [1] [2]. The core recommendation is to use the term "Mesenchymal Stromal Cells (MSCs)" to reflect the predominant in vivo mode of action. The society stipulates that researchers who wish to continue using the "stem cell" terminology must provide experimental evidence of genuine stem cell properties, such as self-renewal and multi-lineage differentiation, in their specific cellular product [1].

This shift is considered corrective, not cosmetic [2]. It aims to:

- Enhance Scientific Clarity: Aligns the cell identity with its established biological function.

- Improve Regulatory Communication: Facilitates more accurate classification and evaluation of cell therapy products.

- Mitigate Public Misunderstanding: Reduces the potential for public confusion and the misuse of the emotionally charged "stem cell" label by unregulated clinics [2].

- Refine Clinical Trial Design: Encourages the development of mechanism-aligned potency assays and clinical endpoints centered on immunomodulation rather than purely regeneration-centric outcomes.

Updated ISCT Criteria: From Minimal Definition to Comprehensive Characterization

The ISCT has substantially refined the identification and characterization criteria for MSCs, moving beyond the minimal standards established in 2006 toward a framework suited for clinical translation.

Table 1: Evolution of ISCT MSC Identification Criteria

| Standard Element | 2006 Standard | 2025 Standard |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Definition | Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | Mesenchymal Stromal Cells (MSCs) |

| Stemness Requirement | Must demonstrate trilineage differentiation | Must provide evidence to use the term "stem" |

| Marker Detection | Qualitative (positive/negative) | Quantitative (thresholds and percentages) |

| Tissue Origin | Not emphasized | Must be specified and considered |

| Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) | Not required | Must assess efficacy and functional properties |

| Culture Conditions | No standard reporting requirement | Detailed parameter reporting required [1] |

Key Updates in the 2025 Framework

- Clarification of Terminology: As discussed, the default nomenclature is now "Mesenchymal Stromal Cells" [1].

- Optimization of Identification Criteria: The updated standards introduce more rigorous requirements for surface marker characterization. While CD73, CD90, and CD105 are retained as basic positive markers, and CD45 is a mandatory negative marker to exclude hematopoietic contamination, reporting must now be quantitative. Researchers must specify the percentage of positive cells and the threshold used for identification via flow cytometry [1].

- Emphasis on Tissue Origin: The new standard requires explicit specification of the tissue source (e.g., bone marrow, adipose tissue, umbilical cord), acknowledging that cells from different origins exhibit distinct phenotypic and functional properties that influence their therapeutic potential [1].

- Introduction of Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs): A major advancement is the incorporation of CQAs, which moves characterization beyond basic phenotyping. CQAs compel researchers to describe the efficacy and functional properties that define the clinical functionality of their MSC product, such as immunomodulatory potency or secretome profile [1].

- Standardization of Culture and Reporting: Detailed reporting on culture conditions, including medium components, passaging methods, and environmental parameters, is now required to enhance reproducibility and transparency across studies [1].

Comparative Analysis of MSCs from Different Tissue Origins

The updated ISCT focus on tissue origin is supported by a body of evidence demonstrating that MSCs from different sources have distinct biological characteristics. This functional heterogeneity is a critical consideration for targeted therapeutic development.

Bone Marrow-Derived MSCs (BM-MSCs)

As the most historically studied type, BM-MSCs are considered the "gold standard" for comparison.

- Immunomodulation: BM-MSCs have been shown to be potent inhibitors of lymphocyte proliferation in vitro [5].

- Clinical Use: They formed the basis for the first FDA-approved MSC product for steroid-refractory pediatric acute GVHD [2]. However, a drawback is the painful isolation process and a cell yield that declines with the age of the donor [6] [3].

Adipose Tissue-Derived MSCs (AT-MSCs)

Adipose tissue is an abundant and readily accessible source of MSCs.

- Proliferation and Yield: Adipose tissue provides a 500-fold higher yield of stem cells per gram of tissue compared to bone marrow [6].

- Immunomodulation: Similar to BM-MSCs, AT-MSCs are potent inhibitors of T-cell proliferation [5]. However, studies have raised safety concerns, as AT-MSC infusions have been associated with pro-coagulant activity in vitro and, in one mouse study, with sudden death, suggesting a need for careful safety monitoring [5].

- Differentiation: They efficiently differentiate into adipogenic, osteogenic, and chondrogenic lineages [6].

Umbilical Cord-Derived MSCs (UC-MSCs)

UC-MSCs, being ontogenically primitive, offer several advantages for allogeneic therapy.

- Proliferation: They exhibit superior proliferative capacity compared to AT-MSCs and BM-MSCs, a characteristic maintained even under serum-free culture conditions [6] [7].

- Immunomodulation: Their immunomodulatory profile can differ. While they may be less potent at directly inhibiting lymphocyte proliferation than BM-MSCs, they are reported to induce a higher regulatory T-cell (Treg)/Th17 ratio, suggesting a different mode of immune regulation [5]. Like AT-MSCs, they also exhibit a higher pro-coagulant potential than BM-MSCs [5].

- Differentiation: While they show strong chondrogenic and osteogenic potential, some studies indicate their adipogenic differentiation may be less efficient than that of AT-MSCs [6] [7].

Table 2: Functional Comparison of MSCs from Different Tissue Sources

| Characteristic | Bone Marrow (BM) | Adipose Tissue (AT) | Umbilical Cord (UC) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relative Cell Yield | Low | Very High (500-fold > BM) | High [6] |

| Proliferation Rate | Moderate | Moderate | High [6] [7] |

| In Vitro T-cell Inhibition | Potent | Potent | Less Potent [5] |

| Treg/Th17 Induction | Not Specified | Higher | Higher [5] |

| Pro-coagulant Risk | Lower | Higher | Higher [5] |

| Osteogenic Potential | High | High | High [6] [7] |

| Adipogenic Potential | High | High | Variable / Moderate [7] |

| Chondrogenic Potential | High | High | High [6] |

| Key Advantages | Established history, potent immunomodulation | High yield, easy access | High proliferation, low immunogenicity |

Experimental Data and Methodologies for Comparison

To ensure robust and reproducible comparisons between MSC sources, standardized experimental protocols are essential.

Key Experimental Workflow

The following diagram outlines a generalized workflow for the isolation, characterization, and functional comparison of MSCs from different tissues.

Detailed Methodologies

1. Isolation and Culture:

- AT-MSCs: Are typically isolated from lipoaspirate or adipose tissue fragments via enzymatic digestion (e.g., collagenase), followed by centrifugation to separate the stromal vascular fraction (SVF) containing the MSCs [6].

- UC-MSCs: Can be isolated using enzymatic methods or explant cultures, where small pieces of Wharton's jelly or cord tissue are placed in culture dishes, allowing MSCs to migrate out [5] [6]. To comply with modern standards, culture should be performed in serum-free medium (SFM) to avoid batch-to-batch variability and safety issues associated with animal serum [7].

2. Immunophenotypic Characterization by Flow Cytometry:

- Method: Cells are harvested, incubated with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies, and analyzed using a flow cytometer.

- Positive Markers (≥95% positive): CD73, CD90, CD105.

- Negative Markers (≤2% positive): CD34, CD45, CD11b or CD14, CD19 or CD79α, and HLA-DR [4] [8]. The 2025 standards require reporting the precise percentage of positive cells for each marker [1].

3. Trilineage Differentiation Assays:

- Adipogenic Differentiation: Cells are cultured in induction medium containing corticosteroids, such as dexamethasone, and indomethacin for 2-3 weeks. Differentiation is confirmed by intracellular lipid droplet accumulation using Oil Red O staining [6] [7].

- Osteogenic Differentiation: Cells are induced with medium containing dexamethasone, ascorbate-2-phosphate, and β-glycerophosphate for 3 weeks. Calcium deposition in the extracellular matrix is visualized with Alizarin Red S staining [6] [7].

- Chondrogenic Differentiation: A pellet culture system is often used, where pellets of MSCs are spun down and cultured in a defined chondrogenic medium with TGF-β for 3 weeks. The formation of sulfated glycosaminoglycans in the cartilage matrix is detected with Alcian Blue staining [6] [7].

4. Immunomodulatory Potency Assays:

- Lymphocyte Proliferation Assay: A standard method to quantify MSC immunomodulatory capacity. MSCs are cocultured with activated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) or T-cells. The inhibition of T-cell proliferation is measured via techniques like 3H-thymidine incorporation or CFSE dilution assay [5]. This assay directly tests a key proposed mechanism of action for many clinical applications.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for MSC Research

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for MSC Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Serum-Free Medium (SFM) | Provides defined, xeno-free culture environment; ensures reproducibility and safety for clinical translation. | Expansion of UC-MSCs under GMP-compliant conditions [7]. |

| TrypLE / Trypsin | Enzymatic detachment of adherent MSCs during subculturing. | Standard passaging of MSC cultures. |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies | Quantitative analysis of surface markers (CD73, CD90, CD105, CD45, etc.) for phenotype validation. | Verification of MSC identity per ISCT criteria [7]. |

| Trilineage Differentiation Kits | Pre-formulated media for inducing adipogenic, osteogenic, and chondrogenic differentiation. | In vitro assessment of multilineage differentiation potential [7]. |

| Recombinant Human IFN-γ | Inflammatory priming agent; enhances MSC immunomodulatory potency by upregulating IDO and PD-L1/2. | Preconditioning MSCs before in vivo administration or in vitro co-culture assays [5]. |

| Lymphocyte Activation Reagents | Activate T-cells in co-culture systems to measure MSC-mediated immunosuppression. | Used in PBMC or T-cell proliferation assays (e.g., with PHA or anti-CD3/CD28 beads) [5]. |

The ongoing debate and subsequent refinement of MSC nomenclature and criteria by the ISCT mark the maturation of the field from exploratory research to targeted therapeutic development. The shift from "stem" to "stromal" is a pivotal correction that aligns terminology with the predominant immunomodulatory and paracrine mechanisms of action observed in clinical settings [2]. The updated 2025 standards, with their emphasis on quantitative reporting, tissue origin, and Critical Quality Attributes, provide a robust framework for developing more consistent, reproducible, and effective MSC-based therapies.

The functional comparisons between tissue sources reveal that there is no single "best" MSC type. Instead, the choice of source—be it bone marrow, adipose tissue, or umbilical cord—should be strategically aligned with the intended clinical application. The future of MSC therapy lies in a precision medicine approach, where a detailed understanding of a cell product's mechanistic profile, informed by the updated ISCT criteria, guides its selection for specific disease pathologies. This evolution in thinking, from a one-size-fits-all "stem cell" to a nuanced toolkit of functionally distinct "stromal cells," promises to unlock the full clinical potential of these remarkable therapeutic agents.

The prevailing classification of Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) often associates them primarily with a mesodermal lineage. However, emerging research reveals a critical exception: a significant population of MSCs, particularly those derived from dental tissues, originates from the ectoderm, specifically the neural crest. This ectodermal heritage endows dental MSCs with unique biological properties and functional predispositions that distinguish them from their mesodermal counterparts, such as Bone Marrow MSCs (BMMSCs) and Adipose-derived Stem Cells (ADSCs). Understanding this distinction is paramount for selecting the optimal MSC source for targeted regenerative applications. This guide provides a comparative analysis of MSCs based on their embryonic origin, consolidating key experimental data and methodologies to inform research and development strategies in regenerative medicine and drug discovery.

Embryonic Origins and Developmental Trajectories

The fundamental difference between dental MSCs and classical MSCs lies in their embryological genesis. While BMMSCs and ADSCs are derived from the mesoderm, dental MSCs originate from the cranial neural crest, an ectodermal structure that gives rise to a vast array of craniofacial tissues [9] [10].

This developmental pathway was conclusively demonstrated using double-transgenic mouse systems (e.g., P0-Cre/Rosa26EYFP and Wnt1-Cre/Rosa26EYFP), which allow for the lineage tracing of neural crest-derived cells. Studies using these models showed that approximately 90% of dental mesenchymal cells are positive for the neural crest lineage marker, whereas only about 7% are derived from the mesoderm (traced by Mesp1-Cre) [10]. This ectodermal origin is not a mere developmental footnote; it imprints a unique molecular and functional signature on dental MSCs, predisposing them toward neurogenic and odontogenic lineages and influencing their secretome and immunomodulatory functions [11] [12].

The diagram below illustrates this developmental divergence.

Comparative Analysis: Ectodermal vs. Mesodermal MSCs

The distinct embryonic origins translate into measurable differences in the biological properties and functional outputs of MSCs. The following tables provide a side-by-side comparison based on current research.

Table 1: Core Properties and Marker Expression

| Property | Ectodermal Dental MSCs (e.g., DPSCs, SHED) | Mesodermal MSCs (e.g., BMMSCs, ADSCs) |

|---|---|---|

| Embryonic Origin | Ectoderm (Cranial Neural Crest) [9] [10] | Mesoderm [11] [13] |

| Key Markers | Positive: CD29, CD44, CD73, CD90, CD105, CD146, STRO-1, Nestin [11] [9] | Positive: CD73, CD90, CD105 [14] [13] |

| Negative: CD14, CD19, CD34, CD45, HLA-DR [11] | Negative: CD34, CD45, HLA-DR [14] | |

| Proliferation & Clonogenicity | High proliferative and colony-forming capacity; SHED > DPSCs > BMMSCs [9] [15] | Moderate proliferative capacity; lower than dental MSCs [9] [13] |

| Immunogenicity | Low immunogenicity; negative for MHC-II [15] | Low immunogenicity |

Table 2: Differentiation Potential and Secretome Profile

| Characteristic | Ectodermal Dental MSCs | Mesodermal MSCs |

|---|---|---|

| Neurogenic Potential | High. Constitutive expression of Nestin, βIII-tubulin; superior neuronal differentiation in vitro [9] [12] [16] | Moderate. Can be induced toward neuronal lineage but with lower efficiency [13] [12] |

| Osteogenic Potential | Strong, primarily toward osteodentinogenesis [13] [17] | Strong, toward osteogenesis [13] |

| Adipogenic Potential | Weak or absent. DPSCs fail to differentiate into adipocytes in vitro [12] [16] | Strong. Readily form lipid droplets [13] [16] |

| Secretome Profile | Enriched in neurotrophic and angiogenic factors; microRNAs involved in oxidative stress and apoptosis pathways [16] | microRNAs more related to cell cycle and proliferation regulation [16] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

To validate the comparative properties outlined above, here are detailed methodologies for two critical experimental paradigms.

Isolation and Culture of Dental Pulp Stem Cells (DPSCs)

This protocol is adapted from established methods for isolating MSCs from human third molars [11] [9].

- Tissue Preparation: Clean the tooth surface thoroughly with disinfectants. Using sterilized dental fissure burs, cut around the cementum-enamel junction to reveal the pulp chamber.

- Pulp Extraction: Gently separate the dental pulp tissue with tweezers.

- Digestion: Rinse the pulp with a basic medium (e.g., α-MEM). Mince the tissue into small pieces (1-2 mm³) and digest in a solution of 3 mg/mL collagenase type I and 4 mg/mL dispase II for 1 hour at 37°C.

- Cell Suspension Preparation: Neutralize the digest with complete medium. Pass the cell suspension through a 70 μM cell strainer to obtain a single-cell suspension.

- Culture: Centrifuge the filtrate and resuspend the cell pellet. Seed cells in culture flasks with a standard growth medium (e.g., α-MEM supplemented with 10-15% FBS, L-ascorbic acid, L-glutamine, penicillin, and streptomycin). Incubate at 37°C in 5% CO₂.

- Expansion: Refresh the medium every 2-3 days. Passage cells upon reaching 80-90% confluence.

The workflow is summarized in the diagram below.

In Vitro Trilineage Differentiation Assay

This is a standard functional assay to confirm MSC multipotency, following ISCT guidelines [14] [16].

Osteogenic Differentiation:

- Culture Medium: Basic medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 50 µM ascorbic acid-2 phosphate, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, and 0.1 µM dexamethasone.

- Procedure: Culture cells for 21 days, changing the medium every 3-4 days.

- Analysis: Detect mineralization by Alizarin Red S staining, which labels calcium deposits red.

Adipogenic Differentiation:

- Culture Medium: Use an adipogenic induction cocktail (typically containing insulin, indomethacin, IBMX, and dexamethasone).

- Procedure: Culture for 14-21 days.

- Analysis: Visualize lipid vacuoles by Oil Red O staining.

Chondrogenic Differentiation:

- Culture Method: Pellet culture or micromass culture in a defined chondrogenic medium containing TGF-β.

- Procedure: Culture for 21-28 days.

- Analysis: Assess cartilage matrix production (proteoglycans) by Toluidine Blue or Alcian Blue staining.

Key Consideration: A definitive outcome of this assay for dental MSCs is their consistent failure to undergo adipogenesis, a key differentiator from mesodermal MSCs [12] [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table lists critical reagents for working with and characterizing dental MSCs.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Collagenase Type I / Dispase II | Enzymatic digestion of collagen and extracellular matrix to isolate cells from dental pulp tissue [11]. | Initial isolation of DPSCs, SHED, SCAP. |

| STRO-1 Antibody | Identifies a key perivascular marker for a primitive, multipotent subpopulation of MSCs via flow cytometry or immunomagnetic sorting [9]. | Enrichment of stem cell-rich fractions from heterogeneous dental MSC populations. |

| Nestin Antibody | Detects the intermediate filament protein Nestin, a neural progenitor marker highly expressed in dental MSCs due to their neural crest origin [9] [16]. | Immunocytochemistry or flow cytometry to confirm ectodermal/neurogenic predisposition. |

| Osteo-Inductive Supplements (Ascorbate, β-Glycerophosphate, Dexamethasone) | Provides critical components to induce and support osteogenic differentiation and matrix mineralization in vitro [16]. | Trilineage differentiation assays; studying dentin regeneration. |

| Alizarin Red S | A diazo dye that binds to calcium salts, used to visualize and quantify calcium deposition in differentiated cultures [16]. | End-point analysis of successful osteogenic differentiation. |

The evidence unequivocally demonstrates that dental MSCs are not merely MSCs from a different anatomical location; they are a distinct class of MSCs shaped by their ectodermal, neural crest ancestry. This origin confers upon them a superior capacity for neurogenesis and a specific bias toward odontogenic, rather than pure osteogenic, differentiation. For researchers and drug development professionals, this knowledge is transformative. It moves the selection of an MSC source from a generic choice to a targeted, rational decision. For applications in nervous system repair, dental pulp regeneration, or leveraging a uniquely programmed secretome, ectoderm-derived dental MSCs present a compelling and powerful alternative to traditional mesodermal sources. Future research will continue to unravel the full therapeutic potential of these specialized cells, solidifying their role in the next generation of regenerative medicine.

Within the complex architecture of nearly every tissue, the perivascular niche serves as a critical in vivo reservoir for mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (MSCs). For decades, MSCs were primarily defined by their in vitro behavior, leaving their native identity and physiological functions poorly understood. Emerging research has since identified two primary perivascular cell types—pericytes and adventitial cells—as the in vivo counterparts to culture-derived MSCs. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these cellular reservoirs, detailing their anatomical positions, marker expression, functional characteristics, and experimental methodologies for their study. Understanding the distinct biological properties of these perivascular stem cells is essential for leveraging their full potential in regenerative medicine and drug development.

The concept of the "perivascular niche" has revolutionized our understanding of mesenchymal stem cell biology. Initially isolated through plastic adherence in long-term cultures, MSCs were later discovered to reside natively in perivascular locations throughout the body [18]. This discovery provided a physiological context for MSCs, linking them to specific anatomical positions and in vivo functions.

Two principal cell types constitute these in vivo reservoirs: pericytes, which envelop capillaries and microvessels, and adventitial cells, located in the outer layer (tunica adventitia) of larger arteries and veins [18]. Collectively termed perivascular stem cells (PSCs), these populations exhibit MSC characteristics in culture, including multipotency, self-renewal capacity, and expression of classic MSC surface markers [18] [19]. Their strategic positioning throughout the vascular tree makes them readily accessible for tissue repair and regeneration, with both populations contributing differentially to tissue homeostasis and pathological processes.

Defining the Cellular Reservoirs

Pericytes

Pericytes are branched, contractile cells embedded within the basement membrane of capillaries and microvessels, making direct contact with endothelial cells through cytoplasmic processes [20] [19]. First described in the 19th century by Rouget and later named "pericytes" by Zimmermann in 1923, these cells play crucial roles in vascular development, stability, and permeability [20] [19] [21].

- Morphology and Distribution: Pericytes exhibit diverse morphologies ranging from typical flat and stellate shapes in the central nervous system to more round shapes in kidneys [20]. Their density varies significantly across tissues, with the highest pericyte-to-endothelial cell ratios found in the central nervous system and retina (approximately 1:1), correlating with more stringent endothelial barrier functions [20].

- Identification Markers: No single specific marker exists for pericytes, necessitating combinatorial approaches. Common markers include PDGFR-β, NG2, CD146, CD13, RGS5, and α-SMA (though α-SMA expression is heterogeneous) [20] [19] [21].

- Developmental Origins: Pericytes originate from multiple embryonic sources, including mesoderm-derived mesenchymal stem cells, neuroectoderm-derived neural crest cells (particularly in the head and thymus), and mesothelium (in coelomic organs) [20].

Adventitial Cells

Adventitial cells reside in the outermost layer of larger blood vessels (tunica adventitia) and represent a phenotypically and anatomically distinct population from pericytes [18]. These cells function as progenitors and can give rise to bona fide MSCs in culture.

- Anatomical Position: Located in the adventitial layer of arteries and veins, these cells are not directly embedded in the capillary basement membrane like pericytes [18].

- Identification: Adventitial cells natively express typical MSC markers (CD73, CD90, CD105) and may express specific markers such as TNAP (tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase) [22].

- Functional Significance: Recent lineage tracing studies demonstrate that TNAP+ adventitial cells contribute to myogenesis during fetal development, differentiating into both skeletal and smooth muscle cells [22].

Table 1: Comparative Characteristics of Perivascular Stem Cells

| Feature | Pericytes | Adventitial Cells |

|---|---|---|

| Anatomical Location | Capillaries & microvessels, embedded in basement membrane | Tunica adventitia of larger arteries & veins |

| Morphology | Branched, stellate to round shapes; cytoplasmic processes | Stromal, fibroblast-like |

| Key Identification Markers | PDGFR-β, NG2, CD146, CD13, RGS5, α-SMA (subset) | CD73, CD90, CD105, TNAP |

| Developmental Origins | Mesoderm, neural crest, mesothelium | Mesoderm |

| Primary Functions | Vascular stability, blood flow regulation, BBB maintenance | Progenitor reservoir, tissue regeneration |

Comparative Analysis of Marker Expression

The reliable identification of perivascular stem cells requires a multifaceted approach combining anatomical position with marker expression profiles. The heterogeneity of these populations necessitates using marker panels rather than relying on single antigens.

Table 2: Comprehensive Marker Expression Profiles

| Marker | Pericytes | Adventitial Cells | Also Expressed By |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD73 | + [20] | + [18] | MSCs, lymphocytes |

| CD90 | + [20] | + [18] | MSCs, hematopoietic stem cells |

| CD105 | + [20] | + [18] | MSCs, endothelial cells |

| CD146 | + [20] [19] | Not reported | Endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells |

| NG2 | + [20] [19] | Not reported | Neural cells, some progenitors |

| PDGFR-β | + [20] [19] | Not reported | Fibroblasts, smooth muscle cells |

| α-SMA | +/- (heterogeneous) [20] [19] | Not typically | Smooth muscle cells, myofibroblasts |

| TNAP | + (subset) [19] | + [22] | Osteoblasts, endothelial cells |

Marker expression can be labile and context-dependent. For instance, pericyte α-SMA expression is minimal in normal skin and brain but increases significantly after tumorigenesis or during activation states [20] [19]. Similarly, NG2 expression is associated with proliferative rather than mature pericyte phenotypes [19]. This dynamic expression underscores the importance of considering physiological and pathological contexts when identifying these cells.

Functional Comparison in Physiology and Pathology

Physiological Roles

Both pericytes and adventitial cells contribute to tissue homeostasis through related but distinct mechanisms:

- Vascular Regulation: Pericytes are essential for angiogenesis, vascular stability, and regulation of capillary diameter and blood flow [20] [19] [21]. They inhibit endothelial cell proliferation through activation of transforming growth factor beta-1 (TGF-β1), particularly during vessel maturation [19]. Adventitial cells serve as progenitors that can be recruited during vascular remodeling and tissue development [22].

- Barrier Function: Pericytes are crucial components of specialized barriers, including the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and retinal barrier [20] [21]. Pericyte deficiency increases vascular permeability, demonstrating their role in maintaining barrier integrity [19].

- Tissue Regeneration: Both cell types contribute to tissue maintenance and repair. Pericytes participate in the regeneration of white adipocytes, skeletal muscle, and dental pulp [18], while TNAP+ adventitial cells contribute to prenatal myogenesis, giving rise to skeletal and smooth muscle cells [22].

Pathological Involvement

Perivascular stem cells play dual roles in disease processes, contributing to both protective and pathogenic mechanisms:

- Fibrosis: Multiple lineage tracing studies have identified pericytes as major myofibroblast progenitors in fibrotic reactions affecting multiple organs [18]. When normal function becomes dysregulated, this differentiation contributes to pathological extracellular matrix accumulation.

- Tumor Progression: Pericytes within the tumor microenvironment modulate cancer initiation and progression, directly impacting metastatic potential and therapy resistance [19]. Specific pericyte subpopulations (type 2: Nestin-GFP+/NG2-DsRed+) are recruited during cancer angiogenesis [19].

- Cerebrovascular Diseases: CNS pericytes constrict capillaries under ischemic conditions, hindering microcirculatory reperfusion even after plaque removal in stroke [21]. They are also implicated in white matter injury, cerebral hemorrhage, and hypoxic-ischemic brain damage [21].

Experimental Protocols for Isolation and Study

Isolation Techniques

Different tissue sources require tailored isolation approaches:

- Bone Marrow-derived MSCs: Isolated from bone marrow aspirate using density gradient centrifugation to collect the mononuclear cell fraction, followed by plastic adherence [23]. Only 0.001-0.01% of cells obtained represent MSCs [23].

- Adipose Tissue-derived MSCs: Isolated from liposuction material through enzymatic digestion with collagenase, followed by centrifugation and washing [23]. Yield is approximately 5 × 10³ stem cells per gram of adipose tissue—500 times higher than equivalent bone marrow [23].

- Umbilical Cord-derived MSCs: Isolated from various umbilical cord components, including Wharton's jelly and perivascular regions, through explant culture or enzymatic digestion [23].

Functional Characterization Assays

Standardized assays evaluate the stem cell properties of isolated perivascular cells:

- Tri-lineage Differentiation: Culture in specific inductive media to assess differentiation potential:

- Osteogenic Differentiation: Cells cultured in media supplemented with β-glycerophosphate, ascorbic acid, and dexamethasone for 2-3 weeks, with mineralization detected by Alizarin Red staining [24] [25].

- Adipogenic Differentiation: Induction with insulin, indomethacin, and IBMX for 3-4 weeks, with lipid vacuoles visualized by Oil Red O staining [24] [25].

- Chondrogenic Differentiation: Pellet culture in TGF-β3-containing media for 3-4 weeks, with sulfated proteoglycans detected by Alcian Blue staining [25].

- Immunomodulatory Assays: Co-culture of MSCs with peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) stimulated with mitogens, measuring T-cell proliferation inhibition and regulatory T-cell induction [5].

- Tube Formation Assay: Evaluation of angiogenic potential by seeding cells on Matrigel and assessing capillary-like network formation [24].

Diagram Title: Perivascular Stem Cell Isolation & Characterization Workflow

Signaling Pathways Governing Perivascular Stem Cell Function

Multiple signaling pathways coordinate the behavior of perivascular stem cells, maintaining their quiescence or activating them in response to injury:

- PDGF-B/PDGFR-β Pathway: This key signaling axis coordinates pericyte recruitment and migration during angiogenesis [19]. Endothelial cells secrete PDGF-B, attracting PDGFR-β-expressing pericytes. Disruption causes microaneurysms due to pericyte deficiency [19].

- TGF-β Pathway: Activation of TGF-β1 mediates the inhibitory effect of pericytes on endothelial cell proliferation, crucial for vessel stabilization [19]. Formation of gap junctions between endothelial cells and pericyte precursors enables production of active TGF-β [19].

- Notch Signaling: Perivascular MSCs in human dental pulp and periodontal tissue express NOTCH3, which participates in niche maintenance [26]. Notch signaling in perivascular stem cells dynamics influences their fate decisions [26].

Diagram Title: Key Signaling Pathways in Perivascular Niches

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Perivascular Stem Cell Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isolation Enzymes | Collagenase | Tissue dissociation for cell isolation | Digests extracellular matrix to release perivascular cells |

| Culture Media | DMEM/F12, Alpha-MEM, MSC Serum-free Media | Cell expansion & maintenance | Provides nutrients and growth factors for cell growth |

| Induction Media | Osteo-, Adipo-, Chondro-Induction Media | Tri-lineage differentiation assessment | Directs stem cell differentiation into specific lineages |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies | Anti-CD73, -CD90, -CD105, -CD146, -NG2, -PDGFR-β | Cell population identification & sorting | Identifies and isolates target cells based on surface markers |

| Histological Stains | Alizarin Red, Oil Red O, Alcian Blue | Detection of differentiation outcomes | Visualizes mineralized matrix, lipids, and proteoglycans |

| Cytokines/Growth Factors | PDGF-BB, TGF-β1, FGF-2 | Functional studies of signaling pathways | Activates specific receptors to study downstream effects |

Application-Oriented Recommendations for Research

Selecting appropriate perivascular stem cell sources depends on specific research objectives:

- Neurological Research: Brain-derived pericytes are optimal for blood-brain barrier studies and neurovascular unit modeling, given their high density in CNS and critical barrier functions [20] [21].

- Musculoskeletal Engineering: Umbilical cord-derived MSCs represent a preferred population with superior proliferation capacity and differentiation potential for bone and cartilage formation [23].

- Vascular Biology Studies: Adventitial cells from larger vessels or specific pericyte subpopulations (type 2: Nestin-GFP+/NG2-DsRed+) are ideal for angiogenesis research [19].

- Immunomodulation Studies: Bone marrow-derived MSCs have well-documented immunosuppressive properties, making them suitable for GVHD and autoimmune disease research [5].

When designing experiments, consider that fetal and neonatal tissue-derived MSCs (from umbilical cord, placenta) generally exhibit greater proliferative capacity and longer in vitro lifespans compared to adult tissue-derived MSCs (from bone marrow, adipose tissue) [23]. However, adult tissue sources may better represent age-related pathological processes.

Mesenchymal Stromal Cells (MSCs) represent a cornerstone of regenerative medicine, with their therapeutic potential largely dictated by their tissue of origin. While MSCs from various sources share fundamental characteristics—adherence to plastic, specific surface marker expression, and multilineage differentiation capacity—their biological properties and functional specializations vary significantly based on their anatomical niche [4]. This comparative analysis examines three prominent MSC sources: bone marrow (BM-MSCs), adipose tissue (ADSCs), and dental pulp (DPSCs), each occupying unique microenvironments that shape their distinctive regenerative profiles. Understanding these tissue-specific differences is paramount for selecting the optimal MSC source for targeted clinical applications, from orthopedic repair to neurovascular regeneration.

Defining Characteristics Across Tissue Niches

The International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) establishes minimal criteria for defining MSCs, including plastic adherence, specific surface marker expression (CD73, CD90, CD105 ≥95%; CD34, CD45, CD14/CD11b, CD79α/CD19, HLA-DR ≤2%), and trilineage differentiation potential [4] [27]. However, beyond these shared characteristics, MSCs from different niches exhibit substantial heterogeneity in their differentiation bias, proliferation kinetics, and molecular signaling, reflecting adaptations to their native tissue environments.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of MSCs from Different Niches

| Feature | Bone Marrow (BM-MSCs) | Adipose Tissue (ADSCs) | Dental Pulp (DPSCs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue Origin | Bone marrow cavity [28] | Subcutaneous adipose tissue (e.g., abdomen, thighs) [27] | Dental pulp chamber [28] |

| Isolation Yield | Low (0.001-0.01% of nucleated cells) [29] | High (~500,000 stem cells/1g adipose tissue) [27] | Variable, depending on pulp volume [13] |

| Key Morphological Traits | Heterogeneous, fibroblast-like [13] | Fibroblast-like, adherent [30] | Spindle-shaped, smaller size [30] |

| Distinctive Markers | STRO-1, CD146 [13] | CD49d (high), Stro-1 (low) [29] | Nestin-positive [30] |

| Proliferation Rate | Moderate, declines with passages [13] [29] | High, stable proliferation [29] | High [30] |

Comparative Differentiation Potential

The trilineage differentiation capacity—osteogenic, adipogenic, and chondrogenic—is a hallmark of MSCs, but the efficacy with which cells from different niches execute these programs varies dramatically, revealing a clear lineage bias rooted in their tissue of origin.

Osteogenic Potential

Bone marrow MSCs, residing in the osseous environment, are considered the gold standard for osteogenesis [31]. Adipose-derived MSCs demonstrate robust but generally inferior osteogenic capability compared to BM-MSCs, with donor-matched comparisons showing BM-MSCs exhibit earlier and higher alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity and calcium deposition [29]. Dental pulp stem cells retain a strong osteogenic/dentinogenic molecular profile, expressing genes like RUNX2, ALP, and COL1A1 even under adipogenic induction conditions, highlighting their inherent commitment to a hard tissue lineage [31].

Adipogenic Potential

Adipose tissue is, unsurprisingly, the most potent source for adipogenic differentiation. ADSCs form numerous, large lipid vesicles and significantly upregulate adipogenic genes like PPARγ2, LPL, and ADIPONECTIN [29]. In contrast, DPSCs exhibit a markedly limited adipogenic potential. When induced, they form only tiny, small lipid droplets and show minimal upregulation of late adipogenic markers [30] [31]. This represents one of the most significant functional distinctions between these MSC populations.

Chondrogenic and Neurogenic Potential

While chondrogenesis is a key defining criterion, comparative studies suggest that BM-MSCs may possess a superior chondrogenic capacity compared to ADSCs [29]. DPSCs, owing to their neural crest origin, demonstrate a pronounced neurogenic propensity. They can differentiate into functionally active neurons and glial cells and secrete neurotrophic factors that support neuroprotection and angiogenesis [28].

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Differentiation Potential

| Differentiation Lineage | Bone Marrow (BM-MSCs) | Adipose Tissue (ADSCs) | Dental Pulp (DPSCs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Osteogenesis | High (Gold Standard) [31] | Moderate [29] | High (osteogenic/dentinogenic) [31] |

| Adipogenesis | Moderate [29] | High [29] | Low/Limited [30] [31] |

| Chondrogenesis | High [29] | Moderate [29] | Not fully characterized |

| Neurogenesis | Limited [13] | Possible [29] | High (Neural crest origin) [28] |

Proliferation, Secretome, and Molecular Signaling

Proliferation and Immunomodulation

ADSCs and DPSCs generally exhibit higher proliferation rates than BM-MSCs [30] [29]. This, combined with the higher yield from adipose tissue, makes ADSCs a practical choice for applications requiring large cell numbers. All MSCs possess immunomodulatory properties, interacting with T cells, B cells, dendritic cells, and macrophages through direct contact and paracrine signaling [4]. The potency of this effect can vary with source and donor health.

Secretome and Extracellular Vesicles

The therapeutic effects of MSCs are increasingly attributed to their secretome—the bioactive molecules they release, including growth factors, cytokines, and extracellular vesicles (EVs) [4] [32]. The composition of this secretome is highly source-dependent. Analysis of conditioned media shows significant variations in the profiles of anti-inflammatory and pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors between ADSCs and DPSCs [30]. While all MSC populations release a comparable number of EVs, ADSCs produce a significantly higher number of smaller exosomes than DPSCs [30]. Crucially, the microRNA (miRNA) cargo within these EVs also differs; DPSC-derived miRNAs are often involved in oxidative stress and apoptosis pathways, while ADSC-derived miRNAs play a larger role in regulating cell cycle and proliferation [30].

Underlying Molecular Pathways

The distinct differentiation biases are governed by differential regulation of key developmental signaling pathways. During adipogenic induction, BM-MSCs downregulate Wnt pathway genes and upregulate NOTCH pathway genes (NOTCH1, NOTCH3, JAGGED1) [31]. Conversely, DPSCs, which resist adipogenesis, maintain their osteogenic/dentinogenic profile (RUNX2, ALP) and upregulate Wnt-specific genes while not activating the NOTCH pathway [31]. The Wnt pathway is a known inhibitor of adipogenesis and promoter of osteogenesis, explaining these divergent commitments.

Experimental Protocols for MSC Comparison

To generate the comparative data cited in this guide, researchers employ standardized in vitro protocols. Below are detailed methodologies for key characterization experiments.

Isolation and Culture

- Bone Marrow MSCs (BM-MSCs): Bone marrow aspirate is diluted, centrifuged, and the cell pellet is resuspended and plated in a culture medium (e.g., DMEM with 10% FBS). Non-adherent cells are removed after 24 hours. Adherent MSCs are expanded and used at passages 3-6 [33] [29].

- Adipose-Derived MSCs (ADSCs): Adipose tissue is washed, minced, and digested with collagenase (e.g., 0.1% collagenase type I). The digest is centrifuged, the pellet is resuspended, and cells are plated. ADSCs are also used at passages 3-6 [30] [29].

- Dental Pulp MSCs (DPSCs): The pulp is extracted, fragmented into 1-2 mm³ pieces, and explants are placed in culture dishes. Cells growing out from the fragments are passaged and used at passages 4-6 [30].

Trilineage Differentiation Assays

- Osteogenic Differentiation: Cells are cultured in growth medium supplemented with osteogenic inducers such as 50 µM ascorbic acid-2 phosphate, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, and 0.1 µM dexamethasone. Differentiation is assessed by alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity and mineralized matrix staining (e.g., Alizarin Red) [30] [29].

- Adipogenic Differentiation: Cells are induced with a cocktail typically containing 0.5 mM isobutylmethylxanthine (IBMX), 1 µM dexamethasone, and 50 µM indomethacin. Differentiated adipocytes are identified by the accumulation of intracellular lipid vesicles stained with Oil Red O or Nile Red [30] [31] [29].

- Chondrogenic Differentiation: Pellet cultures or micromass cultures are maintained in a medium with TGF-β (e.g., TGF-β3) and other supplements. Chondrogenesis is confirmed by Alcian Blue or Safranin O staining for proteoglycans [29].

Secretome and Extracellular Vesicle Analysis

- Conditioned Media (CM) Collection: MSCs are cultured until sub-confluent, washed, and then incubated with a serum-free medium for 24-48 hours. The supernatant (CM) is collected, centrifuged to remove cells and debris, and concentrated or analyzed directly [30].

- Extracellular Vesicle (EV) Characterization: EVs are isolated from CM by sequential ultracentrifugation or size-exclusion chromatography. They are characterized by nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) for concentration and size, and Western blotting for markers like CD63, CD81, and CD9 [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for MSC Isolation, Culture, and Characterization

| Reagent / Kit | Function / Application | Example Use in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Collagenase Type I | Enzymatic digestion of tissues for cell isolation. | Digestion of adipose tissue (ADSC isolation) and bone marrow (ADSC-SVF method) [30] [29]. |

| DMEM / αMEM Medium | Base culture medium for MSC expansion. | Used as the basic medium for culturing all three MSC types, supplemented with FBS [30] [33]. |

| Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) | Essential supplement for cell growth and adhesion. | Added at 10-20% to base medium to support MSC adhesion and proliferation [30] [33]. |

| Osteogenic Induction Kit | Contains components to induce osteoblast differentiation. | Typically includes ascorbic acid, β-glycerophosphate, and dexamethasone [30]. |

| Adipogenic Induction Kit | Contains components to induce adipocyte differentiation. | Typically includes IBMX, dexamethasone, indomethacin, and insulin [31] [29]. |

| Flow Cytometry Antibody Panel | Cell surface immunophenotyping. | Antibodies against CD73, CD90, CD105 (positive) and CD34, CD45, HLA-DR (negative) for MSC definition [4] [29]. |

| Nile Red / Oil Red O | Fluorescent or colorimetric staining of intracellular lipid droplets. | Staining and quantification of adipogenic differentiation [31]. |

| Alizarin Red S | Colorimetric staining of calcium deposits. | Evaluation of mineralized matrix formation in osteogenic differentiation [29]. |

| Extracellular Vesicle Isolation Kit | Enrichment of exosomes and microvesicles from conditioned media. | Used for isolating EVs for downstream NTA and miRNA profiling [30]. |

BM-MSCs, ADSCs, and DPSCs are not interchangeable. Each possesses a unique functional profile shaped by its tissue niche: BM-MSCs are osteogenic champions, ADSCs are prolific and adipogenic, and DPSCs are neuro-vascular potent with a hard tissue commitment. The choice of MSC source should be a deliberate decision aligned with the target clinical application. Future research and clinical translation must move beyond treating MSCs as a monolithic entity and instead leverage these niche-specific specializations to develop more effective and precise regenerative therapies.

Influence of Embryonic Origin on Innate MSC Properties and Plasticity

Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) represent a cornerstone of regenerative medicine, yet their properties and therapeutic potential are profoundly influenced by their tissue of origin. This comparative analysis synthesizes current research on MSCs derived from bone marrow, adipose tissue, umbilical cord, and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), focusing on how embryonic origin dictates their phenotypic, transcriptomic, and functional characteristics. We provide structured experimental data demonstrating that origin-specific differences in differentiation capacity, immunomodulatory potential, and gene expression profiles directly impact their suitability for targeted clinical applications. By integrating quantitative comparisons, detailed methodologies, and signaling pathway visualizations, this guide equips researchers with the necessary framework to select optimal MSC sources for specific therapeutic development, ultimately advancing the rational design of MSC-based therapies.

The term "mesenchyme" originates from embryonic development, describing a loose, migratory cellular organization derived from all three germ layers—ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm—through epithelial-mesenchymal transitions (EMTs) [34]. This developmental history is crucial for understanding adult MSC heterogeneity. While often simplified as mesodermal derivatives, mesenchymal populations in fact have diverse embryonic origins that imprint lasting influences on their biological properties [34].

True to their embryonic nature, MSCs retain multipotent differentiation capacity, typically giving rise to mesodermal lineages like osteoblasts, chondrocytes, and adipocytes [4]. The International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) establishes minimal criteria for defining MSCs: plastic adherence, specific surface marker expression (CD73+, CD90+, CD105+, CD34-, CD45-, CD11b-, CD19-, HLA-DR-), and trilineage differentiation potential [4]. However, MSCs isolated from different tissue sources demonstrate remarkable variation in their functional capabilities, proliferation rates, and molecular signatures—differences rooted in their embryonic derivation and tissue-specific niches [35].

Comparative Analysis of MSC Types by Tissue Origin

Bone Marrow-Derived MSCs (BM-MSCs)

As the most extensively studied type, BM-MSCs represent the historical "gold standard" for MSC research and applications. They originate from the mesodermal germ layer and demonstrate high differentiation potential, particularly toward osteogenic lineages, and strong immunomodulatory properties [4]. BM-MSCs have been successfully used in clinical applications since 1993, with over 950 registered clinical trials submitted to the FDA [35]. Their limitations include invasive harvesting procedures, declining cell quality and quantity with donor age, and relatively slow proliferation rates compared to alternative sources [4].

Adipose Tissue-Derived MSCs (AD-MSCs)

AD-MSCs share comparable therapeutic properties with BM-MSCs but offer practical advantages of easier harvesting and higher yields from lipoaspirate procedures [4]. These cells demonstrate robust adipogenic differentiation capacity and have shown particular promise in applications requiring enhanced angiogenesis and soft tissue regeneration. Like BM-MSCs, they originate from the mesodermal lineage but exhibit distinct gene expression profiles reflective of their adipose tissue niche, including enhanced lipid metabolism pathways [35].

Umbilical Cord-Derived MSCs (UC-MSCs)

UC-MSCs display enhanced proliferation capacity, lower immunogenicity, and distinct immunomodulatory properties compared to adult-derived MSCs, making them particularly suitable for allogeneic transplantation approaches [4]. Their fetal origin contributes to increased telomere length and enhanced replicative potential. UC-MSCs have demonstrated particular efficacy in modulating inflammatory responses and have been applied in trials for graft-versus-host disease and other immune-mediated conditions [35].

iPSC-Derived MSCs (iMSCs)

iMSCs represent a promising approach for generating standardized, high-quality cell populations for therapeutic applications [36]. However, substantial differences exist between iMSCs and primary tissue-derived MSCs. iMSCs consistently demonstrate markedly reduced chondrogenic and adipogenic propensity while maintaining efficient osteogenic differentiation [36]. Transcriptomic analyses reveal that iMSCs express very high levels of KDR and MSX2 with significantly lower PDGFRα compared to BM-MSCs, maintaining a gene expression profile more closely related to vascular progenitor cells (VPCs) than authentic MSCs [36]. This fundamental difference in cellular identity persists through culture expansion and necessitates different inductive conditions for effective differentiation.

Table 1: Functional Properties of MSCs by Tissue Source

| Property | BM-MSCs | AD-MSCs | UC-MSCs | iMSCs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Osteogenic Potential | High | Moderate | Moderate | High |

| Chondrogenic Potential | High | Moderate | Moderate | Low |

| Adipogenic Potential | High | High | Moderate | Low |

| Proliferation Rate | Moderate | Moderate | High | High |

| Immunomodulatory Strength | High | High | Very High | Variable |

| Transcriptomic Similarity to BM-MSCs | Reference | High | Moderate | Low |

Table 2: Surface Marker Expression Profiles Across MSC Types

| Marker | BM-MSCs | AD-MSCs | UC-MSCs | iMSCs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD73 | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ |

| CD90 | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| CD105 | +++ | +++ | +++ | + |

| CD44 | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| CD34 | - | +/- | - | - |

| CD45 | - | - | - | - |

| HLA-DR | - | - | - | - |

| KDR | + | + | + | +++ |

| MSX2 | + | + | + | +++ |

| PDGFRα | +++ | ++ | ++ | + |

Experimental Data: Quantitative Comparisons

Differentiation Capacity

Quantitative analyses of trilineage differentiation potential reveal profound differences between MSC types. In controlled differentiation experiments, BM-MSCs consistently demonstrate robust mineralization in osteogenic conditions (approximately 3-fold increase in calcium deposition), strong lipid accumulation in adipogenic conditions (approximately 80% of cells showing lipid droplets), and abundant proteoglycan production in chondrogenic conditions [4]. In contrast, iMSCs show equivalent or enhanced osteogenic capacity but significantly reduced adipogenic and chondrogenic differentiation, with adipocytes derived from iMSCs expressing significantly lower levels of lineage marker genes (PPAR-γ and ADIPOQ) and chondrocytes showing reduced expression of ACAN and COL2A1 compared to primary MSCs [36].

Gene Expression Profiles

Transcriptomic analyses using RNA sequencing have identified distinct gene expression patterns across MSC types. Hierarchical clustering demonstrates that iMSCs form a separate cluster from primary MSCs, despite similar surface marker expression [36]. BM-MSCs show elevated expression of genes related to skeletal development and hematopoiesis support, while UC-MSCs exhibit enhanced expression of genes involved in developmental processes and immune modulation. iMSCs maintain expression profiles characteristic of vascular progenitor cells, with persistent elevation of KDR and MSX2 even after extended culture [36].

DNA methylation studies further confirm these differences, with iMSCs demonstrating distinct epigenetic patterns compared to BM-MSCs, particularly in genes associated with neuronal and cardiovascular development [37]. When iPSCs were differentiated within 3D fibrin hydrogels, the resulting cells showed upregulated neural development genes rather than MSC-characteristic genes, indicating the strong influence of microenvironment on differentiation trajectory [37].

Table 3: Quantitative Differentiation Potential Across MSC Types

| Differentiation Lineage | BM-MSCs | AD-MSCs | UC-MSCs | iMSCs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Osteogenic Marker Expression | +++ | ++ | ++ | +++ |

| Calcium Deposition | +++ | ++ | ++ | +++ |

| Adipogenic Marker Expression | +++ | +++ | ++ | + |

| Lipid Droplet Formation | +++ | +++ | ++ | + |

| Chondrogenic Marker Expression | +++ | ++ | ++ | + |

| Proteoglycan Synthesis | +++ | ++ | ++ | + |

Methodologies: Key Experimental Protocols

Standard MSC Differentiation Protocol

The fundamental protocol for trilineage differentiation of MSCs involves specific induction cocktails and culture conditions:

Osteogenic Differentiation: Culture MSCs to 70-80% confluence in basal medium, then switch to osteogenic induction medium containing Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 50 μM ascorbic acid, and 100 nM dexamethasone. Culture for 2-4 weeks with medium changes every 3-4 days. Confirm differentiation by Alizarin Red S staining of mineralized matrix [4].

Adipogenic Differentiation: Culture MSCs to complete confluence in basal medium, then switch to adipogenic induction medium containing DMEM with 10% FBS, 1 μM dexamethasone, 0.5 mM isobutylmethylxanthine (IBMX), 10 μg/mL insulin, and 200 μM indomethacin. Culture for 1-3 weeks with medium changes every 3-4 days. Confirm differentiation by Oil Red O staining of lipid droplets [4].

Chondrogenic Differentiation: Pellet 2.5 × 10^5 MSCs by centrifugation and culture in chondrogenic induction medium containing DMEM with 1% FBS, 1% insulin-transferrin-selenium (ITS), 100 nM dexamethasone, 50 μM ascorbic acid, and 10 ng/mL transforming growth factor-beta 3 (TGF-β3). Culture for 3-4 weeks with medium changes every 3-4 days. Confirm differentiation by Alcian Blue staining of proteoglycans [4].

iMSC Generation from iPSCs

Generate iMSCs using the embryoid body (EB) outgrowth method: Maintain iPSCs in suspension culture for 8 days to form EBs, then transfer to gelatin-coated plates in EB formation medium (80% KO-DMEM, 20% FBS, 1 mM L-glutamine, 14 μM β-mercaptoethanol, 1% nonessential amino acids). When outgrown cells form confluent areas, passage to new gelatin-coated flasks, removing EB clumps with a 40 μm cell strainer. Transition cells to MSC culture medium when majority display MSC-like morphology [36]. Note that resulting iMSCs require different inductive conditions for chondrogenic and adipogenic differentiation compared to primary MSCs, reflecting their vascular progenitor cell signature [36].

Directed Differentiation of MSCs into Endothelial Cells

For efficient differentiation of MSCs into functional endothelial cells, transduce MSCs with lentivirus encoding the transcription factor ER71. Culture transduced cells in endothelial differentiation medium supplemented with TGF-β inhibitor (SB431542), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and ascorbic acid for 7 days. Using this protocol, approximately 75.4 ± 4.5% of MSCs differentiate into endothelial cells as defined by double-positivity for VE-cadherin/PECAM1 [38]. The resulting cells demonstrate endothelial characteristics and functions, with potentiated immune tolerance properties mediated by IKAROS, a direct transcriptional target of ER71 [38].

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

The therapeutic effects of MSCs are mediated through complex signaling pathways that vary by tissue source. MSCs from all sources release bioactive molecules including growth factors, cytokines, and extracellular vesicles that modulate the local cellular environment, promote tissue repair, angiogenesis, and cell survival, and exert anti-inflammatory effects [4]. Key pathways include:

Immunomodulatory Pathways: MSCs interact with various immune cells (T cells, B cells, dendritic cells, macrophages) through direct cell-cell contacts and release of immunoregulatory molecules like prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) [4]. When primed with interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF), MSCs uniformly polarize toward a Th1 phenotype characterized by expression of immunosuppressive factors IDO, IL-10, CD274/PD-L1, and IL-4 [35].

Differentiation Pathways: Osteogenic differentiation is regulated through Wnt signaling (including CCN4/WISP-1) and BMP pathways, while adipogenesis follows PPAR-γ and C/EBPβ cascades [35]. The distinct differentiation propensities of iMSCs compared to primary MSCs result from their alternative transcriptional regulation, with maintained expression of vascular progenitor genes despite standard MSC surface marker expression [36].

The following diagram illustrates key signaling pathways that govern MSC differentiation and immunomodulation, highlighting how different MSC types vary in their activation of these pathways:

The experimental workflow for generating and characterizing MSCs from different sources involves specific processes that significantly impact the resulting cell properties:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for MSC Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Culture Media | KO-DMEM, DMEM/F12, α-MEM | Basal media for MSC expansion and maintenance |

| Serum Supplements | Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), Human Platelet Lysate (hPL) | Provide essential growth factors and adhesion molecules |

| Differentiation Inducers | Dexamethasone, β-glycerophosphate, IBMX, Insulin, TGF-β3 | Direct lineage-specific differentiation |

| Cytokines/Growth Factors | VEGF, FGF, EGF, IFN-γ, TNF | Modulate MSC function and priming |

| Surface Marker Antibodies | CD73, CD90, CD105, CD34, CD45, HLA-DR | Phenotypic characterization by flow cytometry |

| Transcriptional Regulators | ER71, KLF2, TAL1 (for endothelial differentiation) | Direct cell fate conversion |

| Enzymatic Dissociation Agents | Trypsin/EDTA, Collagenase, Accutase | Cell passaging and tissue dissociation |

| Matrix Scaffolds | Gelatin, Collagen I, Fibrin Hydrogels | 2D/3D culture systems for differentiation studies |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors | SB431542 (TGF-β inhibitor), ROCK inhibitor | Enhance differentiation efficiency and cell survival |

| Staining Reagents | Alizarin Red, Oil Red O, Alcian Blue | Detection of differentiated lineages |

The embryonic origin and tissue source of MSCs fundamentally determine their functional properties and therapeutic specialization. BM-MSCs remain the gold standard for skeletal regeneration, AD-MSCs excel in soft tissue and angiogenic applications, UC-MSCs offer superior immunomodulation for allogeneic settings, and iMSCs provide scalability with distinct differentiation biases. Understanding these origin-dependent differences enables researchers to select optimal MSC sources for specific therapeutic goals.

Future research directions should focus on establishing more refined molecular signatures for different MSC populations, developing precision priming protocols to enhance specific functions, and creating standardized differentiation protocols that account for source-specific requirements. As the field advances toward more targeted applications, recognizing the inherent biological differences between MSC types will be essential for developing safe, effective, and reproducible cell-based therapies.

From Bench to Bedside: Isolation, Characterization, and Therapeutic Mechanisms

Standardized Protocols for MSC Isolation from Different Tissues (BM-MSCs, AD-MSCs, UC-MSCs, DP-MSCs)

Mesenchymal Stromal Cells (MSCs) represent a cornerstone of regenerative medicine due to their multipotent differentiation capabilities, immunomodulatory properties, and relative ease of isolation from various tissue sources. The therapeutic potential of MSCs is heavily influenced by their tissue of origin, which dictates their biological characteristics, differentiation potential, and functional behavior in clinical applications. This comparative guide provides a systematic analysis of isolation methodologies, phenotypic characterization, and functional capabilities of MSCs derived from four prominent sources: bone marrow (BM-MSCs), adipose tissue (AD-MSCs), umbilical cord (UC-MSCs), and dental pulp (DP-MSCs). Understanding these distinctions enables researchers to select the most appropriate MSC source for specific therapeutic applications, thereby optimizing experimental outcomes and clinical efficacy.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Key Characteristics Across MSC Tissue Sources

| Characteristic | BM-MSCs | AD-MSCs | UC-MSCs | DP-MSCs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolation Yield | Low (0.001-0.01% of nucleated cells) [39] | High (500,000 cells/gram tissue) [30] | High [39] | Variable [30] |

| Proliferation Capacity | Moderate, age-dependent [40] | High [30] | Very High, fetal origin [40] [41] | High, Nestin-positive [30] |

| Key Positive Markers | CD73, CD90, CD105 [4] | CD29, CD73, CD90 [30] [42] | CD73, CD90, CD105 [4] | CD73, CD90, CD105 [4] |

| Key Negative Markers | CD34, CD45, HLA-DR [4] | CD34, CD45 [42] | CD34, CD45, HLA-DR [4] | CD34, CD45, HLA-DR [4] |

| Osteogenic Potential | Strong [4] | Variable by depot [42] | Strong [4] | Strong [4] |

| Adipogenic Potential | Strong [4] | Strong, superior in perirenal vs. subcutaneous [42] | Moderate [4] | Weak/Absent [30] |

| Chondrogenic Potential | Strong [4] | Moderate [42] | Strong [4] | Strong [4] |

| Immunomodulatory Strength | Strong, well-characterized [4] | Strong [35] | Very Strong, enhanced innate immune response [41] | Moderate [30] |

| Transcriptomic Stability | Age-related decline [40] | Donor-dependent [30] | High, stable to late passage [41] | Limited data |

Table 2: Quantitative Differences in Marker Expression and Functional Capacity

| Parameter | Specific Comparison | Experimental Finding | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD105 Expression | Perirenal vs. Subcutaneous AD-MSCs (Hanwoo) | P-AMSCs: 26.3% vs. S-AMSCs: 1.2% [42] | Anatomical depot influences marker profile. |

| Proliferation Rate | UC-MSCs vs. AD-MSCs | DPSCs were consistently smaller and had a higher proliferation rate than ADSCs [30] | Source impacts expansion potential for scaling. |

| Adipogenic Outcome | DP-MSCs vs. Other MSCs | All primary cell lines possessed typical MSC characteristics, apart from the inability of DPSCs to perform adipogenesis [30] | Critical for lineage-specific application selection. |

| Transcriptomic Profile | Fetal (UC) vs. Adult (BM, AD) MSCs | 2,208 upregulated and 2,594 downregulated DEGs; enriched pathways in fetal MSCs: glycolysis, cholesterol biosynthesis, TNF-α signaling [41] | Fetal and adult MSCs are biologically distinct. |

Standardized Isolation Protocols

Bone Marrow-Derived MSCs (BM-MSCs)

Methodology: The established protocol for isolating BM-MSCs relies on density gradient centrifugation to separate mononuclear cells from other bone marrow components [39]. Bone marrow samples are diluted with Dulbecco's Phosphate-Buffered Saline (DPBS) in a 1:1 ratio and carefully layered onto a Ficoll-Paque Premium solution. This is followed by centrifugation at 400 g for 30 minutes at 20°C with the brake disengaged [41]. The resulting mononuclear cell layer is harvested, washed with DPBS to remove residual separation media, and centrifuged again. The cell pellet is then resuspended in a low-glucose Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (LG-DMEM) supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) and antibiotics. Cells are plated at a high density (1 × 10⁵ cells/cm²) and maintained in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO₂. The culture medium is replaced regularly to remove non-adherent cells, and adherent MSCs are expanded through trypsin-EDTA detachment upon reaching 80% confluency [41].

Adipose Tissue-Derived MSCs (AD-MSCs)

Methodology: Two primary methods are prevalent for isolating AD-MSCs, both beginning with tissue washing and removal of connective tissue and blood vessels.

- Enzymatic Digestion (SVF): The washed adipose tissue is subjected to digestion using collagenase (e.g., Collagenase 1A) overnight at 37°C with agitation [30]. The digested slurry is centrifuged to pellet the Stromal Vascular Fraction (SVF). The pellet is then resuspended in a basic medium (e.g., αMEM or LG-DMEM) supplemented with 10% FBS and plated on tissue culture dishes [30].

- Mechanical Fragmentation (Explant): As an alternative to enzymatic digestion, the adipose tissue can be minced into small fragments (1-2 mm³) and explanted directly onto culture dishes. These fragments are allowed to adhere, and culture medium (e.g., αMEM with 20% FBS) is added. AD-MSCs migrate out from the tissue explants over 1-2 weeks, after which they can be detached and expanded [30].

Umbilical Cord-Derived MSCs (UC-MSCs)

Methodology: The umbilical cord must be thoroughly washed with DPBS to remove blood contaminants before processing [39] [41].

- Enzymatic Digestion: The cord tissue is dissected and treated with collagenase type I (e.g., 0.1% concentration) for several hours at 37°C with gentle agitation [41]. The digested tissue is filtered through a 100-μm cell strainer to remove undigested fragments. The filtrate is centrifuged, and the cell pellet is resuspended in culture medium and plated.

- Explant Method (MCE): The Minimal Cube Explant (MCE) method involves cutting the washed umbilical cord into small 2-4 mm cubes using surgical scissors [41]. These tissue pieces are placed directly in culture dishes and allowed to adhere firmly for about an hour in an incubator. Culture medium (LG-DMEM with 10% FBS) is then gently added. MSCs that grow out from the explants are termed "smumf cells" and exhibit high proliferative capacity and genomic stability [41].

Dental Pulp-Derived MSCs (DP-MSCs)

Methodology: Sound teeth (e.g., third molars with open apex) are cleaned and cut at the amelo-cement junction using a sterile diamond disc [30]. The dental pulp is carefully extracted from the pulp chamber and radicular canals using a sterile dental instrument. The isolated pulp is then fragmented into 1-2 mm³ pieces using a scalpel. These pieces are washed, seeded onto culture plates, and maintained in a basic medium supplemented with 10% FBS [30]. Cells migrating from the pulp explants typically form a monolayer within 2-4 weeks. For comparative studies, DP-MSCs can be isolated from specific regional compartments of the pulp, such as the coronal pulp (CPSCs) and radicular pulp (RPSCs) [30].

Molecular Basis and Signaling Pathways

The functional properties of MSCs, including their stemness, proliferation, and differentiation, are governed by a complex network of intrinsic genetic regulators and extrinsic signaling pathways. Key transcription factors such as TWIST1, OCT4, SOX2, and various HOX genes play critical roles in maintaining MSC stemness and preventing senescence [40]. For instance, TWIST1 promotes proliferation and suppresses senescence by increasing EZH2, which silences senescence genes like p14 and p16 via H3K27me3 chromatin modification [40]. The distinct "HOX code" expression pattern is stable throughout life and reflects the tissue origin of MSCs, influencing their differentiation bias and functional properties [40].

Diagram 1: Key molecular regulators of MSC stemness and their functional outcomes. Transcription factors like TWIST, OCT4, SOX2, and HOX genes coordinately regulate critical processes such as proliferation, self-renewal, and differentiation, while simultaneously inhibiting senescence pathways.

Single-cell transcriptomic analyses further reveal fundamental distinctions between true stem cells and MSCs. Stem cells express critical self-renewal genes (SOX2, NANOG, POU5F1, SFRP2, DPPA4, SALL4, ZFP42, MYCN) that are absent in MSCs. Conversely, MSCs express functional markers (TMEM119, FBLN5, KCNK2, CLDN11, DKK1) not found in stem cells, highlighting their different biological identities [43].

Experimental Workflow for MSC Characterization

Diagram 2: Comprehensive MSC characterization workflow. The process begins with tissue harvest and isolation via various methods, progresses through essential in vitro characterization (immunophenotyping, proliferation, differentiation), and culminates in advanced functional analyses to determine therapeutic potential.

Trilineage Differentiation Assessment

A fundamental criterion for defining MSCs is their capacity for trilineage differentiation into osteogenic, adipogenic, and chondrogenic lineages under specific in vitro conditions [30] [4] [35].

Osteogenic Differentiation: MSCs are seeded at 3 × 10³ cells/well in 48-well plates and cultured in an osteogenic induction medium. This medium typically consists of DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 50 µM ascorbic acid-2 phosphate, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, and 0.1 µM dexamethasone [30]. Successful differentiation is confirmed by alkaline phosphatase staining and Alizarin Red S staining of mineralized deposits after 2-3 weeks.

Adipogenic Differentiation: Cells are induced using a medium containing DMEM, 10% FBS, 0.5 mM isobutylmethylxanthine (IBMX), 1 µM dexamethasone, 10 µM insulin, and 200 µM indomethacin [30]. Lipid accumulation within cytoplasmic droplets, the hallmark of adipogenesis, is visualized after 2-3 weeks using Oil Red O staining. Quantitative differences can be significant, with one study showing P-AMSCs achieving 10.95% differentiation compared to 7.26% in S-AMSCs [42].

Chondrogenic Differentiation: Chondrogenesis is typically induced in a pellet culture system. Approximately 2.5 × 10⁵ MSCs are centrifuged to form a micromass pellet, which is then cultured in a serum-free chondrogenic medium. This medium is supplemented with 1% ITS (Insulin-Transferrin-Selenium), 100 nM dexamethasone, 50 µM ascorbic acid-2 phosphate, and 10 ng/mL TGF-β3 [30]. The resulting cartilage pellets are assessed after 3-4 weeks by histological staining for sulfated proteoglycans with Alcian Blue or Safranin O.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for MSC Isolation and Characterization

| Reagent/Chemical | Primary Function | Application Example | Source/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collagenase Type I | Enzymatic digestion of extracellular matrix. | Isolation of AD-MSCs (SVF) and UC-MSCs. | Sigma-Aldrich [30] [41] |

| Ficoll-Paque Premium | Density gradient medium for cell separation. | Isolation of mononuclear cells from bone marrow. | GE Healthcare [41] |

| Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) | Critical supplement for cell culture media, providing growth factors and nutrients. | Standard component (10-20%) for MSC expansion and maintenance. | Gibco [30] [41] |

| Trypsin-EDTA | Proteolytic enzyme solution for detaching adherent cells. | Passaging and subculturing of adherent MSCs. | Sigma-Aldrich [30] [41] |