Stem Cell Fate Mapping: A Comprehensive Guide to Tracking Techniques and Their Applications in Research and Therapy

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of modern stem cell fate mapping techniques, a critical toolkit for researchers and drug development professionals.

Stem Cell Fate Mapping: A Comprehensive Guide to Tracking Techniques and Their Applications in Research and Therapy

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of modern stem cell fate mapping techniques, a critical toolkit for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of cell fate tracking, from historical methods to the latest breakthroughs in single-cell resolution and live imaging. We detail the mechanisms, strengths, and limitations of key methodological families, including genetic barcoding, CRISPR-based editing, and multi-modal imaging. The content further guides troubleshooting and optimization strategies to address common challenges like label dilution and toxicity. A direct, evidence-based comparison of established and emerging technologies equips scientists to select the optimal method for their specific research goals, whether in fundamental developmental biology, regenerative medicine, or clinical transplantation studies.

Defining Cell Fate: Core Principles and the Evolution of Lineage Tracing

What is Cell Fate? Understanding Differentiation, Migration, and Engraftment

Cell fate encompasses the ultimate identity and function a cell acquires through the processes of differentiation, migration, and engraftment. Understanding these mechanisms is paramount in developmental biology and regenerative medicine. This guide objectively compares the predominant experimental techniques used in stem cell fate mapping, detailing their methodologies, applications, and limitations. We provide structured comparisons of quantitative data and essential reagent solutions to inform research and drug development strategies.

Defining Cell Fate in Biology

Cell fate is defined as the ultimate differentiated state to which a cell has become committed [1]. This commitment is the endpoint of a developmental process where a less specialized cell transitions into a distinct, functional cell type, such as a neuron, blood cell, or muscle cell [2]. The determination of cell fate is a tightly regulated process, governed by the interplay of intrinsic factors (e.g., transcription factors and epigenetic regulators within the cell) and extrinsic factors (e.g., signaling molecules from the cell's environment) [3] [2].

Once a cell is determined, its fate is generally stable and irreversible under normal physiological conditions, meaning a cell destined to become a brain cell will not transform into a skin cell [2]. This is crucial for the maintenance of complex multicellular organisms. The process involves not just the commitment but also the subsequent differentiation, which entails the actual biochemical, structural, and functional changes that result in the specific cell type [2]. Furthermore, for stem cells in therapeutic contexts, fate also involves successful migration to the correct anatomical niche and engraftment—the process of settling, surviving, and functioning within a host tissue [4] [5].

Mechanisms Governing Cell Fate

The specification of cell fate occurs through several conserved modes, primarily through autonomous and conditional specification, and is critically maintained by epigenetic regulation.

Modes of Specification

There are three primary mechanisms by which a cell becomes specified for a particular fate [2]:

- Autonomous Specification: This is a cell-intrinsic process where a cell develops based on inherited maternal cytoplasmic determinants (proteins, RNAs) asymmetrically distributed during cell division. The cell's fate is determined by these internal factors, independent of signals from neighboring cells. This leads to mosaic development, where the removal of a specific cell results in a missing structure, as the remaining cells cannot compensate [2].

- Conditional Specification: This is a cell-extrinsic process that relies on signals from neighboring cells or concentration gradients of morphogens. A cell's fate is determined by its interactions and position within the embryo, a concept known as positional value. This mechanism allows for plasticity; if a cell is removed, another can change its fate to compensate, and a cell transplanted to a new location may adopt a new fate based on its local environment [2].

- Syncytial Specification: A hybrid mechanism observed in insects, where morphogen gradients operate within a syncytium—a cell with multiple nuclei—before cellular boundaries form. The nuclei are influenced by these gradients in a concentration-dependent manner [2].

The Role of Epigenetic Regulation

Cell fate determination is profoundly influenced by epigenetic mechanisms that regulate gene expression without altering the DNA sequence itself [2]. These mechanisms create a cellular "memory" that maintains identity and resists changes in fate. Key epigenetic regulators include:

- DNA methylation: Typically adds methyl groups to DNA, repressing gene activity.

- Histone modifications: Acetylation generally loosens chromatin structure to enhance gene transcription, while other modifications can have repressive effects.

- Chromatin remodeling: Dynamic alteration of nucleosome positioning by remodelers makes specific genomic regions accessible or inaccessible to transcription factors [2].

These modifications are orchestrated by enzymes like DNA methyltransferases and histone acetyltransferases, which respond to both intrinsic programs and extrinsic cues, thereby locking in cell fate decisions [2].

Techniques for Cell Fate Mapping: A Comparative Analysis

Tracking cell fate—a process known as lineage tracing—is fundamental to understanding normal development and disease. The gold standard for cellular trajectory inference, lineage tracing involves marking a progenitor cell and tracking all its descendants to reveal their fate choices and relationships [6]. The following section compares key technologies used in this field.

Comparison of Fate Mapping Techniques

Table 1: Comparison of Key Cell Fate Mapping Techniques

| Technique | Core Principle | Key Applications | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Observation [6] | Visual tracking of cells using light microscopy. | Studying transparent embryos (e.g., zebrafish). | Non-invasive, simple, and provides direct visual data. | Limited to transparent organisms with low cell counts; not suitable for complex tissues. |

| Fluorescent Protein Labeling (e.g., Brainbow) [2] [6] | Cre-recombinase-driven stochastic expression of multiple fluorescent proteins. | Mapping neuronal connectivity [6], stem cell proliferation, and organ homeostasis. | Enables visualization of multiple cells and their spatial relationships simultaneously. | Limited number of colors; challenging to control timing/dosage for single-cell resolution [6]. |

| Viral Barcoding [6] [7] | Ex vivo transduction of cells with a retroviral/library containing unique DNA barcode sequences. | Tracking hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) clones after transplantation [6] [7]. | Allows simultaneous tracking of thousands of clones; high information yield from a single experiment [6]. | Limited to dividing cells; potential for viral silencing; non-random integration may affect cell behavior [6]. |

| In Situ Barcoding (e.g., Polylox, CARLIN) [6] [7] | In vivo generation of high-diversity DNA barcodes via Cre-lox recombination [6] or CRISPR/Cas9 editing [7]. | Studying native hematopoiesis [6], clonal dynamics in development and disease. | No transplantation needed; studies fate in unperturbed physiological conditions; very high barcode diversity [6]. | Complexity of generating and breeding engineered mouse models. |

| Natural Barcoding [6] | Using naturally accumulated somatic mutations (nuclear or mitochondrial) as lineage markers. | Retrospective lineage tracing in human tissues; aging studies. | Safe and non-invasive; can be applied to human samples without genetic manipulation. | Low mutation rate requires costly deep sequencing; analysis is complex and retrospective [6]. |

| Single-Cell Multi-Omics [7] | Combining lineage barcodes with single-cell RNA-seq or ATAC-seq. | Reconstructing lineage trajectories and linking clone identity to molecular state. | Reveals transcriptional and epigenetic heterogeneity driving fate decisions. | High cost; computational complexity for data integration. |

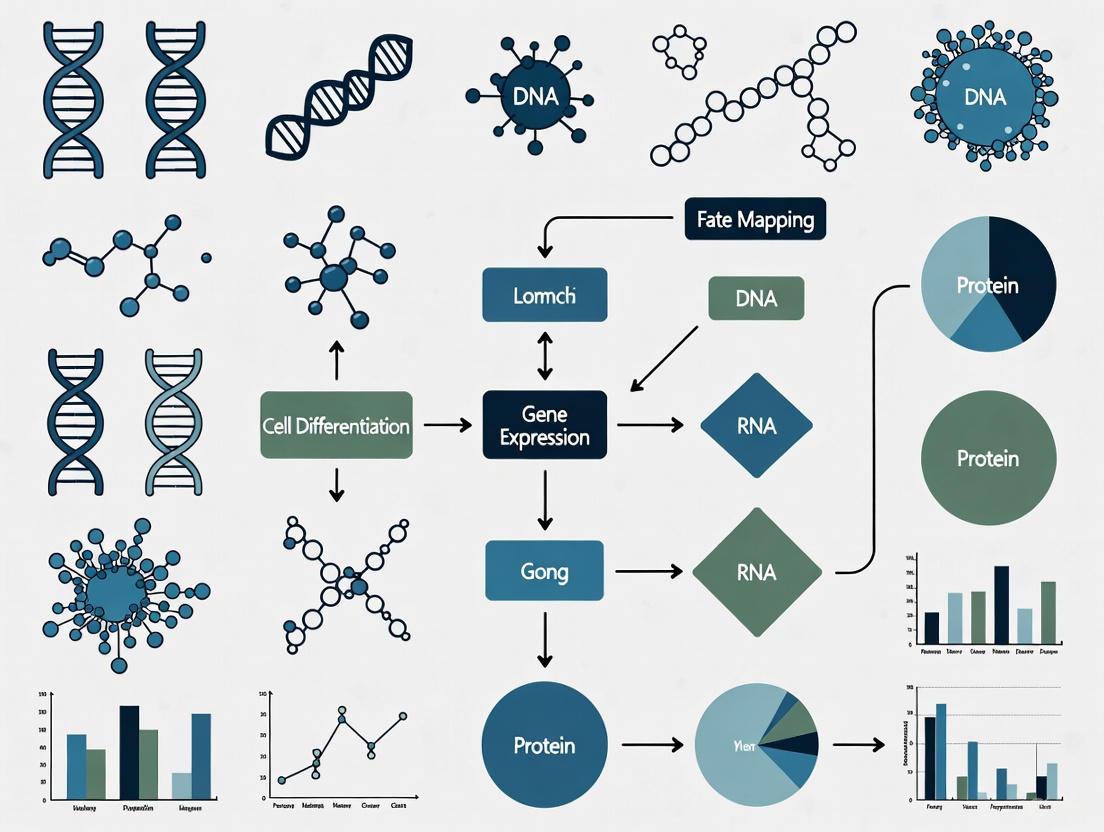

Visualizing a Fate Mapping Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for a DNA barcoding-based fate mapping experiment, integrating both in vivo and ex vivo approaches.

Experimental Protocols in Focus

To provide practical insight, we detail two foundational protocols for studying cell fate in the context of hematopoiesis.

Protocol: Genetic Barcoding of Hematopoietic Stem Cells (HSCs)

This protocol is used to track the clonal output of individual HSCs after transplantation [6] [7].

- Barcode Library Production: Generate a complex library of lentiviral vectors, each containing a unique random DNA sequence (barcode) of 20-30 nucleotides, flanked by universal primer sequences for later amplification.

- HSC Isolation and Transduction: Isolate phenotypically defined HSCs (e.g., Lineage⁻ Sca-1⁺ CD117⁺ CD48⁻/lo CD150⁺) from donor bone marrow. Culture the cells and transduce them with the viral barcode library at a low multiplicity of infection (MOI << 1) to ensure most cells receive a single, unique barcode.

- Transplantation: Transplant the transduced HSCs into lethally irradiated or immunodeficient recipient mice.

- Longitudinal Tracking: Collect peripheral blood and bone marrow samples at various time points post-transplantation (e.g., 4, 8, 16 weeks, 1 year).

- DNA Extraction and Barcode Amplification: Isolve genomic DNA from sorted cell populations (e.g., myeloid cells, T cells, B cells). Amplify the barcode regions using PCR with primers specific to the universal flanking sites.

- High-Throughput Sequencing and Analysis: Sequence the PCR products and map the barcode reads to the original library. Quantify the abundance of each barcode in different cell populations and over time to assess clonal contributions and lineage biases.

Protocol: Enhancing HSC Migration and Engraftment

This functional assay assesses and enhances the homing ability of HSCs, a critical aspect of their fate after transplantation [5].

- HSC Subpopulation Isolation: Isolate distinct HSC subpopulations, such as Short-Term (ST)-HSCs (Flk2⁻CD34⁺) and Long-Term (LT)-HSCs (Flk2⁻CD34⁻), using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS).

- Characterization of Homing Effectors:

- Analyze expression of sialyl Lewis-X (sLex), a ligand for E-selectin critical for the first step of bone marrow homing, via flow cytometry.

- Analyze expression of CXCR4, the receptor for SDF-1α (CXCL12) critical for the second homing step.

- Analyze expression of CD26, a peptidase that deactivates SDF-1α.

- Functional Modulation:

- Fucosylation: Treat HSCs with recombinant human fucosyltransferase VI (rhFTVI) to enhance sLex expression and E-selectin binding.

- CD26 Inhibition: Treat HSCs with a CD26 inhibitor (e.g., Diprotin A) to preserve local SDF-1α gradients.

- In Vitro Migration Assay: Load modulated and control HSCs into a transwell system. Place SDF-1α in the lower chamber. Quantify the number of cells that migrate through the membrane after a set period.

- In Vivo Engraftment Assay: Transplant pretreated HSCs into recipient mice. Analyze bone marrow at early time points to measure homing efficiency, and at later time points (e.g., 4-6 months) to evaluate long-term multi-lineage engraftment in primary and secondary recipients.

Quantitative Data from Fate Mapping and Engraftment Studies

Table 2: Summary of Key Experimental Findings from Cited Research

| Experimental Context | Key Measured Variable | Result / Quantitative Finding | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Native Thrombopoiesis Fate Mapping [8] | Contribution of "short route" vs "long route" to platelet production | The two pathways make comparable contributions in steady state. | Thrombopoiesis is not a single pathway but the sum of functionally distinct routes. |

| HSC Homing Mechanism [5] | sLex expression on Flk2⁻CD34⁺ ST-HSCs | >60% of cells were sLex⁺. | ST-HSCs are intrinsically well-equipped for the initial homing step (E-selectin binding). |

| HSC Homing Mechanism [5] | sLex expression on Flk2⁻CD34⁻ LT-HSCs | <10% of cells were sLex⁺. | LT-HSCs have deficient first-step homing, which can be a target for enhancement. |

| HSC Homing Mechanism [5] | Effect of CD26 inhibition on LT-HSC migration | CD26 inhibition enhanced engraftment in vivo. | Targeting the second homing step (CXCR4/SDF-1) can overcome LT-HSC migration deficits. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Cell Fate Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Cre-loxP System [2] [6] | Enables cell-type-specific and inducible genetic recombination. | Activating fluorescent reporters (e.g., Brainbow) or generating genetic barcodes (e.g., Polylox) in specific cell lineages. |

| Lentiviral Barcode Libraries [6] [7] | Introduces heritable, unique DNA sequences into cells for clonal tracking. | Massively parallel lineage tracing of hematopoietic stem cells after transplantation. |

| Fluorescent Proteins (e.g., GFP, RFP) [4] [2] | Visual labeling of live cells and their progeny. | Tracking engraftment, migration, and differentiation of transplanted neural stem cells. |

| Recombinant Fucosyltransferase (rhFTVI) [5] | Enzymatically modifies cell surface proteins to enhance E-selectin ligand expression. | Improving the homing efficiency of short-term HSCs for transplantation. |

| CD26 Inhibitors (e.g., Diprotin A) [5] | Protects SDF-1α from degradation by inhibiting the CD26 peptidase. | Enhancing the chemotactic migration and engraftment of long-term HSCs. |

| Marker Enrichment Modeling (MEM) [9] | A computational algorithm that generates quantitative labels for cell populations based on enriched features. | Objectively characterizing and comparing novel cell types identified by single-cell cytometry or transcriptomics. |

The journey from a progenitor to a determined cell involves a sophisticated interplay of autonomous and conditional signals, locked in place by epigenetic mechanisms. Mastery of cell fate is not merely an academic pursuit but a cornerstone of advanced regenerative medicine and therapeutic development. Techniques like genetic barcoding and single-cell multi-omics have moved the field from observing static hierarchies to dynamically mapping fate choices with clonal resolution. Furthermore, functional protocols that enhance migration and engraftment are directly translatable to improving clinical outcomes in areas like hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. As the toolkit evolves, the ability to precisely track, predict, and ultimately direct cell fate will continue to unlock new frontiers in treating degenerative diseases and cancer.

For decades, developmental biologists have sought to reconstruct the intricate lineage trees that trace how a single fertilized egg gives rise to the extraordinary complexity of a complete organism. Traditional methods provided glimpses—static snapshots of cellular relationships that offered limited insight into the dynamic temporal sequences of developmental decisions. The central challenge in stem cell research has been transforming these static observations into comprehensive, dynamic lineage trees that capture not only the "what" and "where" of cell fate, but the "when" and "how" of developmental progression. This comparison guide examines the revolutionary technologies reshaping stem cell tracking and fate mapping, objectively evaluating their performance characteristics, experimental requirements, and applications for research and drug development.

Part 1: The Evolution of Lineage Tracing Technologies

Historical Foundations and Technical Limitations

Classical lineage tracing approaches relied on direct visual observation, dye labeling, and enzymatic reporters, which provided foundational insights but suffered from significant technical constraints. Early methods using Nile Blue staining in amphibian blastula and nucleoside analogues (BrdU, EdU) enabled initial fate mapping but were limited by label dilution through cell divisions and inability to resolve complex lineage relationships [10]. The introduction of fluorescent proteins and Cre-loxP recombinase systems in the late 20th century marked a substantial advancement, allowing heritable genetic labeling of specific cell populations [10]. However, these approaches still faced resolution limitations—homogeneous labeling made distinguishing individual clones within populations difficult, and sparse labeling strategies increased experimental burden while reducing reproducibility [10].

Modern Technology Categories

Contemporary lineage tracing technologies fall into three principal categories, each with distinct mechanisms and applications:

Imaging-Based Approaches leverage advanced microscopy and fluorescent reporter systems for spatial resolution. The Brainbow and Confetti systems utilize stochastic Cre-loxP recombination to generate multicolored fluorescent tags, enabling visual distinction of adjacent clones in tissues [11] [10]. Mosaic Analysis with a Repressible Cell Marker (MARCM) identifies lineage branches through mitotic recombination [10]. More recently, dual recombinase systems (e.g., Cre-loxP/Dre-rox) have enabled simultaneous tracing of multiple cell populations, as demonstrated in studies mapping regenerative bone formation and alveolar epithelial stem cells [10].

DNA Recording Systems utilize genomic edits as heritable lineage marks. CRISPR-based barcoding introduces cumulative insertions/deletions (indels) at specific genomic loci during cell divisions, creating evolving lineage-specific barcodes [11] [12]. Base editing systems generate more predictable mutations, while "DNA typewriter" systems record the sequence of cellular events [12]. The Polylox system employs Cre-loxP recombination to generate diverse DNA barcodes without viral integration [11] [7]. These systems excel at reconstructing complex lineage relationships across extensive cell divisions.

Computational Inference Methods leverage single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data to reconstruct developmental trajectories. Algorithms like CytoTRACE 2 use deep learning to predict developmental potential from transcriptomic data [13]. Pseudotemporal ordering methods reconstruct lineage relationships based on transcriptional similarity, effectively arranging cells along differentiation continua [14]. While powerful for hypothesis generation, these inference-based approaches provide probable rather than definitively demonstrated lineage relationships [12] [14].

Part 2: Comparative Performance Analysis of Leading Technologies

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 1: Comprehensive Performance Comparison of Lineage Tracing Technologies

| Technology | Maximum Resolution | Temporal Recording | Throughput | Lineage Tree Accuracy | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brainbow/Confetti | Single-cell (spatial) | None (static label) | Moderate (imaging constraints) | High for clone identification | Limited color palette; spectral overlap |

| CRISPR Barcoding | Single-cell (molecular) | Continuous (cumulative edits) | High (sequencing-based) | Very high (empirical recording) | Requires CRISPR delivery; potential toxicity |

| Polylox Barcoding | Single-cell (molecular) | Inducible (Cre-dependent) | High (sequencing-based) | High (diverse barcode library) | Limited to model organisms; Cre toxicity concerns |

| CytoTRACE 2 | Single-cell (computational) | Inferred (pseudotime) | Very high (transcriptomic) | Moderate (inferential) | Computational inference only; no empirical validation |

| scRNA-seq Trajectory | Single-cell (computational) | Inferred (pseudotime) | Very high (transcriptomic) | Moderate (inferential) | Destructive sampling; trajectory inference only |

Experimental Validation Data

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics from Validation Studies

| Technology | Clonal Reconstruction Accuracy | Maximum Clones Tracked | Long-term Stability | Cross-platform Compatibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CytoTRACE 2 | 60% higher correlation vs. methods [13] | 406,058 cells in atlas [13] | N/A (computational) | 9 platforms validated [13] |

| CRISPR Barcoding | 84-93% bootstrap support [11] | Several thousand cells [11] | Heritable genomic edits | Requires compatible delivery system |

| Polylox | High (low barcode collision) [7] | >1,000 clones [11] | Stable genomic integration | Limited to engineered mouse models |

| Integration Barcodes | Moderate (retroviral silencing) [11] | Thousands simultaneously [11] | Variable (silencing concerns) | Broad (viral transduction) |

Part 3: Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

CytoTRACE 2 Computational Framework

Objective: Predict absolute developmental potential from scRNA-seq data without experimental perturbation [13].

Methodology Details:

- Training Data Curation: Compiled atlas of 33 human/mouse scRNA-seq datasets with experimentally validated potency levels, spanning 406,058 cells and 125 standardized cell phenotypes [13].

- Architecture: Gene Set Binary Network (GSBN) with binary weights (0 or 1) to identify discriminative gene sets for potency categories [13].

- Feature Selection: Multivariate gene expression programs that suppress batch effects through competing representations and training set diversity [13].

- Output Generation: Two primary outputs: (1) potency category with maximum likelihood, and (2) continuous potency score from 1 (totipotent) to 0 (differentiated) [13].

- Validation: Weighted Kendall correlation against known developmental orderings across 62 developmental time points in mouse models [13].

Workflow Diagram:

CRISPR Lineage Tracing Experimental Protocol

Cell Preparation and Barcode Delivery:

- Vector Design: Construct lentiviral vectors containing barcode arrays with multiple gRNA target sites and unique molecular identifiers [11] [12].

- Cell Transduction: Transduce target cells at low multiplicity of infection (MOI < 0.3) to ensure single barcode integration per cell [7].

- Selection and Expansion: Apply antibiotic selection for stable integrants, then expand cell population for sufficient diversity [12].

In Vivo Lineage Tracing:

- Animal Modeling: For in situ approaches, use engineered models like CARLIN mice containing Cas9 and barcode arrays [7].

- Barcode Activation: Induce Cas9 expression (doxycycline or tamoxifen) to initiate stochastic barcode editing [7].

- Temporal Sampling: Harvest tissues at multiple time points to capture lineage progression [11].

Barcode Recovery and Analysis:

- DNA Extraction: Process tissues for high-quality genomic DNA [11].

- Barcode Amplification: PCR amplify barcode regions using flanking primers [7].

- High-Throughput Sequencing: Sequence libraries on Illumina platforms [11].

- Lineage Reconstruction: Bioinformatic processing to identify indel patterns and reconstruct phylogenetic trees [11] [12].

Workflow Diagram:

Part 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Lineage Tracing

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Lineage Tracing Applications

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reporter Systems | R26R-Confetti, Brainbow, Polylox | Visual barcode generation | Stochastic labeling efficiency; spectral separation |

| CRISPR Components | CARLIN model, Base editors, Prime editors | DNA barcode generation | Editing efficiency; off-target effects |

| Recombinases | Cre-ERT2, Dre, Flp | Inducible genetic recombination | Leakiness; toxicity with prolonged expression |

| Viral Delivery | Lentiviral barcode libraries, Retroviral vectors | High-efficiency gene delivery | Insertional mutagenesis; silencing concerns |

| Detection Reagents | Antibody panels, In situ hybridization probes | Barcode detection and visualization | Signal-to-noise ratio; multiplexing capacity |

| Sequencing Kits | Single-cell RNA-seq, Barcode amplification | High-throughput barcode recovery | Amplification bias; sequencing depth requirements |

Part 5: Applications and Validation in Biological Systems

Hematopoietic Stem Cell Tracking

Transplantation studies utilizing DNA barcoding have revealed the remarkable heterogeneity of hematopoietic stem cell fates, demonstrating temporal oligoclonality where a limited number of dominant clones sustain long-term hematopoiesis [7]. Integration site analysis of retrovirally transduced HSPCs has shown variable clonal contributions to mature blood lineages, revealing lineage biases and clonal drift over time [7]. The Polylox system has enabled in situ barcoding without transplantation, uncovering native hematopoietic dynamics and revealing how stress conditions alter clonal output patterns [11] [7].

Cancer Stem Cell Dynamics

Lineage tracing has transformed our understanding of tumor heterogeneity and therapeutic resistance. In acute myeloid leukemia, CytoTRACE 2 potency predictions aligned with known leukemic stem cell signatures, while in oligodendroglioma, it identified multilineage potential in subpopulations [13]. CRISPR lineage tracing has enabled reconstruction of tumor evolution trees, identifying branching patterns and mutation sequences that drive progression and treatment resistance [13].

Developmental Biology Applications

In mammalian development, CytoTRACE 2 correctly captured the progressive decline in potency across 258 phenotypes during mouse development without requiring data integration or batch correction [13]. Multicolor Confetti reporters have enabled visualization of clonal expansion and patterning in epithelial tissues, revealing how progenitor cells contribute to tissue architecture during organogenesis [10].

The optimal lineage tracing technology depends on specific research questions and experimental constraints. CRISPR-based barcoding excels for high-resolution reconstruction of complex lineage relationships across extended timescales, though it requires genomic manipulation. Imaging-based approaches provide unparalleled spatial context and real-time observation capabilities but face throughput limitations. Computational inference methods like CytoTRACE 2 offer non-invasive analysis of existing scRNA-seq data with strong performance for developmental potential assessment but remain inferential rather than empirical.

For research and drug development applications, the integration of multiple complementary technologies provides the most comprehensive insights—combining empirical lineage recording with transcriptional profiling and spatial context to transform static snapshots into dynamic, mechanistic understanding of cell fate decisions. As these technologies continue to evolve, they promise to unravel the fundamental principles governing stem cell behavior, tissue regeneration, and disease pathogenesis with increasingly precise resolution.

Lineage tracing remains an essential approach for understanding cell fate, tissue formation, and human development [10]. This field has evolved from simple microscopic observation to sophisticated genetic labeling that can track single cells across time and space. The core principle involves establishing hierarchical relationships between cells to reconstruct developmental trajectories and fate decisions [10]. This progression has fundamentally transformed developmental biology, stem cell research, and regenerative medicine, providing increasingly precise tools to answer one of biology's most fundamental questions: what becomes of a cell and its descendants?

The historical journey of lineage tracing reflects broader technological revolutions in biology. From its origins in direct observation of transparent embryos to today's integration of sequencing and imaging technologies, each advancement has expanded our ability to decipher cellular narratives in increasingly complex organisms and contexts [10] [15] [6]. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of these techniques, their experimental protocols, and their applications in modern biomedical research.

Historical Techniques and Their Methodologies

Direct Observation and Dye-Based Labeling

The earliest lineage tracing methods relied on visual monitoring of cell behavior. In the late 1800s, Charles Whitman reported the first direct observation of germ layer differentiation in leeches using light microscopy [10] [6]. Data collection was entirely dependent on visual observations of an experimenter in real time, limiting experimental models to those with observable changes via available microscopy [10].

Dye labeling techniques represented the first major technological leap. Eric Vogt fate-mapped an amphibian blastula in 1929 using Nile Blue as a non-specific label [10]. Later approaches used:

- Carbocyanine dyes to stain cell membranes and track migration patterns [15]

- Tritiated thymidine for long-term, non-toxic in vivo labeling [15]

- Nucleoside analogues (BrdU, EdU) incorporated into cellular DNA and subsequently labeled with fluorescent dyes [10]

A significant limitation of these approaches was label dilution proportional to cell proliferation, reducing tracking accuracy over time [10] [15].

Table 1: Historical Lineage Tracing Techniques

| Technique | Era | Key Features | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Observation | Late 1800s | Real-time visual monitoring, minimal technical requirements | Limited to transparent embryos, subjective, low-throughput |

| Dye Labeling (Nile Blue) | 1929 | First non-specific labeling method | Label dilution, limited specificity |

| Nucleoside Analogues (BrdU/EdU) | Mid-late 20th century | Identifies proliferating populations | Label dilution with proliferation, requires fixation |

| Enzyme Reporters (β-galactosidase) | 1980s | First transgenic approaches, stable genetic labeling | Requires substrate addition, lower resolution |

| Fluorescent Proteins (GFP) | 1994 | Endogenous reporting without external stimulus | Potential phototoxicity, limited color palette |

The Recombinase Revolution

The late 20th century introduced genetic recombinase systems that transformed lineage tracing. The Cre-loxP system, discovered in P1 bacteriophage and implemented in mammalian cells in 1988, became a fundamental tool [10] [15]. Cre recombinase recognizes 34-base pair loxP sequences, enabling precise DNA recombination including deletion, inversion, or exchange of gene sequences [15].

Key implementations include:

- LoxP-Stop-loxP (LSL) system: Cre-mediated excision of a STOP cassette activates reporter gene expression [15]

- Double-floxed Inversion Orientation (DIO/DO): Uses two incompatible pairs of inverted loxP sites for more precise control [15]

- CIAO (cross-over insensitive ATG-out) strategy: Places the ATG start codon within loxP sites to prevent nonspecific expression [15]

These systems enabled permanent genetic labeling of specific cell populations and all their progeny, overcoming the dilution problem of dye-based methods [15].

Modern Genetic Labeling Technologies

Advanced Recombinase Systems

Modern lineage tracing has evolved beyond single recombinase systems to address limitations of "non-specific expression" and insufficient spatiotemporal resolution [15]. Key advancements include:

Dual recombinase systems (e.g., Cre-loxP + Dre-rox) enable simultaneous labeling of distinct or overlapping cell lineages [10] [15]. These orthogonal recombinase systems consist of engineered enzyme-substrate pairs that operate independently without cross-reactivity [15]. Applications include:

- Determining origin of regenerative cells in remodelled bone [10]

- Investigating cellular origins of alveolar epithelial stem cells post-injury [10]

- Discriminating senescent cell populations expressing analogous markers [10]

Multicolour lineage tracing approaches like Brainbow and R26R-Confetti report cassettes capable of expressing multiple fluorescent proteins through stochastic Cre-loxP-mediated excision [10] [6]. These enable:

- Clonal analysis at single-cell level in various tissues [10]

- Discrimination of different cells upon Cre activation [6]

- Intravital imaging to trace cell origin and proliferation in real time [10]

Genetic Lineage Tracing Principle

Single-Cell Lineage Tracing (SCLT) and Barcoding Technologies

Single-cell sequencing technology propelled lineage tracing into high-throughput analysis of cell fates at single-cell resolution [15] [6]. SCLT maps cell lineage connectivity at single-cell resolution, becoming the best tool for exploring cellular differentiation heterogeneity [6].

Integration barcodes utilize DNA fragments with extensive sequence variations to label individual cells:

- Retroviral barcoding: Uses vectors with random sequence tags that integrate into chromosomes [6]

- Enables long-term tracking of clonal descendants from host cells [6]

- Allows examination of clonal relationships between cellular compartments [6]

Polylox barcodes represent artificial DNA recombination loci that enable endogenous barcoding using Cre-loxP recombination [6]. CRISPR barcodes utilize cumulative CRISPR/Cas9 insertions and deletions (InDels) as genetic landmarks for reconstructing lineage hierarchies [6].

Base editors represent a recent breakthrough, introducing informative sites to document cell division events with faster mutation rates, allowing recording of more mitotic divisions and construction of more detailed cell lineage trees [6].

Table 2: Modern Genetic Lineage Tracing Technologies

| Technology | Mechanism | Resolution | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cre-loxP Systems | Site-specific recombination | Cell population | General lineage tracing, gene knockout |

| Dual Recombinase (Cre+Dre) | Orthogonal recombination systems | Multiple lineages | Distinguishing overlapping lineages |

| Brainbow/Confetti | Stochastic fluorescent protein expression | Clonal (multicolor) | Visualizing clonal expansion, cell interactions |

| Viral Barcoding | Random viral integration sites | Thousands of clones | Hematopoietic stem cell tracking, large-scale fate mapping |

| CRISPR Barcoding | CRISPR/Cas9-induced mutations | Single-cell | Developmental lineage trees, cancer evolution |

| Base Editors | Targeted nucleotide editing | High-resolution phylogenetic | Detailed cell division history, organ development |

Imaging Modalities for Cell Tracking

Comparative Analysis of Imaging Techniques

Various imaging modalities have been developed to track stem cells in living organisms, each with distinct advantages and limitations [16] [17].

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) provides high-resolution 3D imaging at the anatomical level [16] [17]. Contrast agents include:

- Gadolinium (Gd³⁺): T1-weighted contrast agent that appears hyperintense [16]

- Superparamagnetic iron oxide (SPIO): T2-weighted agent that generates hypointense signals [16] [17]

- Manganese: "Positive" T1 contrast agent that enters cells via voltage-gated Ca²⁺ channels [16]

Radionuclide imaging (PET/SPECT) offers high sensitivity for detecting small cell numbers:

- Direct labeling: Uses ¹¹¹In-oxyquinoline or ⁹⁹mTc-hexamethylpropylene amine oxime [17]

- Can detect 10⁴-10⁵ cells in small animal models [17]

- Applications in tracking endothelial progenitor cells and mesenchymal stem cells [17]

Optical imaging includes bioluminescence and fluorescence approaches:

- Bioluminescence: Uses luciferase enzymes with substrates like luciferin [17]

- Fluorescence proteins: GFP, RFP, and related variants [17]

- Quantum dots: Semiconductor nanocrystals with tunable emission wavelengths [17]

Magnetic Particle Imaging (MPI) is an emerging technology that directly images SPION distribution with high sensitivity and linear quantification [16].

Stem Cell Tracking Workflow

Performance Comparison of Imaging Modalities

Table 3: Quantitative Comparison of Stem Cell Imaging Modalities

| Imaging Modality | Spatial Resolution | Tissue Penetration | Sensitivity (Cell Detection) | Temporal Resolution | Clinical Translation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRI | 25-100 µm | No limit | 10⁵-10⁶ cells | Minutes-hours | Established |

| Magnetic Particle Imaging (MPI) | ~1 mm | No limit | Single cell (theoretical) | Milliseconds-seconds | Preclinical |

| PET | 1-2 mm | No limit | 10⁴-10⁵ cells | Seconds-minutes | Established |

| SPECT | 1-2 mm | No limit | 10⁴-10⁵ cells | Minutes | Established |

| Bioluminescence | 3-5 mm | 1-2 cm | 10²-10⁴ cells | Seconds-minutes | Limited |

| Fluorescence | 2-3 mm | <1 cm | 10³-10⁵ cells | Seconds-minutes | Emerging |

| Quantum Dots | 2-3 mm | <1 cm | 10³-10⁵ cells | Seconds-minutes | Preclinical |

Experimental Protocols and Research Reagents

Key Experimental Workflows

Cre-loxP Lineage Tracing Protocol:

- Transgenic mouse generation: Cross mice expressing Cre recombinase under tissue-specific promoters with reporter strains containing loxP-STOP-loxP sequences before fluorescent proteins [10] [15]

- Induction timing: Administer tamoxifen for CreER[T2] systems at desired developmental stages [10]

- Tissue collection: Harvest tissues at appropriate timepoints post-induction [10]

- Analysis: Process for microscopy, flow cytometry, or single-cell RNA sequencing [10] [6]

Viral Barcoding Workflow:

- Barcode library design: Create diverse DNA barcode sequences in lentiviral or retroviral vectors [6]

- Cell transduction: Infect target cells (e.g., hematopoietic stem cells) with barcode library at low MOI to ensure single integrations [6]

- Transplantation: Introduce barcoded cells into animal models [6]

- Timepoint sampling: Collect cells or tissues at multiple timepoints [6]

- Barcode sequencing: Amplify and sequence barcodes to quantify clonal contributions [6]

CRISPR Lineage Tracing Method:

- Engineered cassette: Introduce CRISPR target sites and unique barcode arrays into genome [6]

- In vivo editing: Express Cas9 to induce accumulating mutations during development [6]

- Single-cell sequencing: Perform scRNA-seq to capture both mutations and transcriptomes [6]

- Lineage reconstruction: Use mutation patterns to build phylogenetic trees [6]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Lineage Tracing

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Site-Specific Recombinases | Cre, Dre, FlpO | DNA recombination at specific target sites | Genetic labeling, gene activation |

| Reporter Genes | GFP, RFP, tdTomato, LacZ | Visualizing labeled cells and progeny | Microscopy, flow cytometry |

| Inducible Systems | CreER[T2], Tet-On/OFF | Temporal control of recombination | Precise fate mapping at specific timepoints |

| Viral Vectors | Lentivirus, Retrovirus | Gene delivery and barcode library introduction | Hematopoietic stem cell tracking |

| CRISPR Components | Cas9, gRNAs, Base editors | Introducing heritable mutations for barcoding | Single-cell lineage tracing |

| Contrast Agents | SPIO, Gd³⁺, ¹¹¹In-oxine | Cell labeling for non-invasive imaging | MRI, PET, SPECT tracking |

| Nucleoside Analogues | EdU, BrdU | Labeling proliferating cells | Short-term lineage tracing |

Applications in Biomedical Research

Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine

Lineage tracing has provided crucial insights into stem cell plasticity, differentiation, and tissue regeneration [15]. In neurology, neural stem cells (NSCs) have been tracked after transplantation to treat conditions like Parkinson's disease, brain trauma, and stroke [16]. These studies revealed migration routes, survival rates, and functional integration of transplanted cells [16].

Cardiac stem cell therapy monitoring has utilized multiple imaging modalities to address contradictory results in clinical trials [17]. Studies tracking ¹¹¹In-labeled endothelial progenitor cells found only 4.7% retention in infarcted myocardium, highlighting delivery efficiency challenges [17].

Cancer Biology and Disease Modeling

Lineage tracing has determined mutations critical to cancer progression and lineage-specificity for therapeutics [10]. In hematology, single-cell lineage tracing technologies unravel heterogeneity of hematopoietic stem cell function and the heterogeneity of malignant tumor cells [6].

CRISPR-based lineage tracing with base editors has been applied to Drosophila melanogaster, generating high-quality cell phylogenetic trees with several thousand internal nodes, enabling estimation of symmetric and asymmetric cell division balances during development [6].

The evolution of lineage tracing from direct observation to sophisticated genetic labeling represents one of the most transformative journeys in modern biology. While direct observation provided foundational principles, the field has progressed through dye labeling, transgenic approaches, and now single-cell barcoding technologies [10] [15] [6].

Current frontiers include multimodal integration of sequencing with spatial information, improved computational tools for lineage reconstruction, and retrospective tracing using natural barcodes in human samples [10] [6]. The continued innovation in this field promises to further unravel the complex dynamics of development, disease, and regeneration at unprecedented resolution.

The ideal future of lineage tracing lies in seamlessly integrating multiple approaches—combining the specificity of genetic labeling with the sensitivity of modern imaging and the throughput of single-cell technologies—to create comprehensive fate maps across entire organisms throughout their lifespan.

In stem cell biology, understanding clonal dynamics (the behavior and evolution of a single cell's progeny), progenitor hierarchies (the structured relationships between stem cells and their differentiated descendants), and fate restriction (the progressive limitation of a cell's developmental potential) is fundamental. Researchers employ various fate-mapping techniques to track these processes in living organisms. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the predominant methodologies, detailing their experimental protocols, applications, and performance to inform tool selection for basic research and drug development.

Comparative Analysis of Fate-Mapping Techniques

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, performance, and applications of major fate-mapping approaches.

| Technique | Core Mechanism | Key Performance Metrics (Typical Results) | Key Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Fate Mapping (e.g., Cre-lox) [18] [19] | Uses cell-type-specific promoters to drive Cre recombinase, which permanently activates a heritable reporter gene (e.g., GFP) in target cells and all their progeny. | - Lineage Resolution: Single-cell to population-level.- Temporal Control: High (with inducible systems like CreERT2).- Clonal Tracking: Possible with multi-color reporters (e.g., Confetti).- Stability: Permanent, long-term marking. | - Tracking developmental origins of adult tissues and organs [19].- Studying immune cell development and function [18].- Mapping diverse macrophage subsets in various tissues [18]. | - Requires generation of transgenic animals.- Promoter specificity is critical and can be a limitation.- Background recombination can occur in inducible systems. |

| Clonal Dynamics Analysis (via Somatic Mutations) [20] | Leverages naturally accumulated somatic mutations (e.g., in clonal hematopoiesis) as endogenous barcodes for retrospective lineage tracing. | - Clonal Contribution: Can quantify a clone's contribution to platelet, erythroid, myeloid, B, and T cell lineages [20].- Fate Bias Identification: Identifies clones with restricted output (e.g., PEMB or PEM-only) [20].- Clonal Longevity: Can trace clones established decades prior to analysis [20]. | - Studying steady-state human hematopoiesis, especially in aged populations [20].- Identifying lineage-restricted stem cells and their stability over years [20]. | - Typically applied in aged individuals where clones have expanded sufficiently.- Requires deep, error-corrected DNA sequencing and complex phylogenetic analysis. |

| Viral Vector-Based Lineage Tracing [21] | Uses viral vectors (e.g., Retroviruses, AAVs) to deliver and integrate a reporter or fate-altering gene (e.g., Neurogenin2) into target cells. | - Cell-Type Specificity: Varies by vector and promoter; Retroviruses target proliferating cells [21].- Reprogramming Efficiency: Retroviral 9SA-Ngn2 successfully converted astrocytes to neurons; AAVs led to artefactual neuronal labeling [21].- Immunogenicity: Retroviruses induce stronger inflammation than AAVs [21]. | - Direct neuronal reprogramming of glial cells [21].- Fate conversion studies in the brain. | - Retroviruses (Mo-MLVs): Infect only dividing cells, superior for fate conversion of proliferative glia [21].- AAVs: Can infect post-mitotic cells; prone to artefactual labeling with strong neurogenic factors [21]. |

| Computational Fate Mapping (e.g., CellRank 2, STORIES) [22] [23] | Infers lineage relationships and dynamics from single-cell omics data (e.g., RNA-seq, spatial transcriptomics) using algorithms, without physical labels. | - Multiview Data Integration: Can combine RNA velocity, pseudotime, experimental time points, and spatial coordinates [23].- Terminal State Identification: CellRank 2 consistently recovered terminal states in human hematopoiesis [23].- Spatial Coherence: STORIES outperforms other methods in learning spatially-informed cell fate landscapes [22]. | - Reconstructing differentiation trajectories from snapshot data [23].- Studying the impact of spatial environment on cell fate decisions [22].- Analyzing clinical single-cell datasets from cancer immunotherapy [24]. | - Is a computational inference, not a direct observation of lineage.- Requires high-quality, often large-scale, single-cell datasets.- Performance depends on the algorithm and data modality. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Techniques

Genetic Fate Mapping with Inducible Cre-loxP

This protocol is used for precise, temporally controlled lineage tracing in transgenic mice [18].

Key Reagents:

- Transgenic Mouse Line: Expressing CreERT2 fusion protein under a cell-type-specific promoter (e.g., Cx3cr1CreERT2 for myeloid cells).

- Reporter Mouse Line: With a floxed-stop cassette upstream of a reporter gene (e.g., GFP) in a permissive locus like Rosa26.

- Tamoxifen: The inducer drug.

Workflow:

- Animal Crosses: Cross the driver Cre line with the reporter line to generate experimental offspring.

- Induction: Administer tamoxifen to the animals (e.g., via intraperitoneal injection or oral gavage) at the desired developmental or experimental time point. Tamoxifen binds to CreERT2, allowing it to translocate to the nucleus.

- Recombination: Nuclear CreERT2 catalyzes the removal of the floxed-stop cassette in the target cells, leading to permanent expression of the reporter gene.

- Tissue Harvest and Analysis: After a desired chase period, harvest tissues and analyze them using flow cytometry or immunohistochemistry to track the location and differentiation of the labeled progeny.

Clonal Dynamics Analysis via Somatic Mutations

This method leverages natural mutations for retrospective lineage tracing in humans [20].

Key Reagents:

- Bone Marrow or Blood Samples: From healthy aged donors or those with clonal hematopoiesis.

- Error-Corrected Targeted DNA Sequencing (ECTS) Panels: For sensitive detection of low-frequency somatic mutations in known driver genes (e.g., DNMT3A, TET2).

- Cell Sorting Equipment: For purifying specific hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell (HSPC) populations and mature lineages.

Workflow:

- Mutation Screening: Screen DNA from bulk bone marrow mononuclear cells using ECTS to identify clonal driver mutations.

- Cell Sorting: Purify distinct cell populations (e.g., HSCs, myeloid cells, B cells, T cells, erythroid progenitors, megakaryocyte progenitors) using FACS.

- Clonal Contribution Assessment: Quantify the variant allele frequency of the identified mutations in each purified cell population to determine the clone's contribution to each lineage.

- Phylogenetic Analysis: Perform whole-genome sequencing on single-cell-derived colonies to retrospectively infer the phylogenetic history and timing of the clone's origin.

Viral Vector-Mediated Fate Mapping and Reprogramming

This protocol is for tracking or converting the fate of specific cell populations in vivo, such as in the brain [21].

Key Reagents:

- Viral Vectors: Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus (Mo-MLV) for targeting proliferating glia or Adeno-Associated Viruses (AAVs) with flexed cassettes for potential specificity.

- Genetic Fate-Mapping Mouse Lines: (e.g., GFAP::Cre) to label starter cells (astrocytes).

- EdU (5-ethynyl-2'-deoxyuridine): For birth-dating endogenous neurons.

Workflow:

- Model and Injury: Use a transgenic mouse (e.g., GFAP::Cre) and subject it to a cortical stab wound injury to induce glial proliferation.

- Viral Injection: Three days post-injury, inject viral vectors (e.g., Mo-MLV-CAG-9SA-Ngn2-IRES-mScarlet) into the injury site.

- Control for Artefacts: Employ two key controls:

- Starter Cell Labeling: Use genetic fate mapping to confirm that converted neurons originate from the labeled astrocytes.

- Endogenous Neuron Labeling: Use EdU birth-dating to rule out artefactual labeling of pre-existing neurons.

- Analysis: After a few weeks, analyze brain sections via immunohistochemistry to identify virally transduced, fate-mapped, and birth-dated cells to confirm true astrocyte-to-neuron conversion.

Visualizing Fate-Mapping Concepts and Workflows

Genetic Fate Mapping with Cre-loxP

Clonal Dynamics in Hematopoiesis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

This table details essential materials used in the featured experiments [20] [18] [21].

| Research Reagent | Function in Fate Mapping | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Tamoxifen-Inducible Cre (CreERT2) | Enables temporal control of lineage tracing; Cre activity is induced only upon tamoxifen administration. | Precisely marking a specific cell population at a defined time point in development or adulthood [18]. |

| Multicolor Reporter Mice (e.g., Confetti) | Allows for stochastic, multi-color labeling of cells, enabling visual distinction between different clones within a tissue. | Clonal analysis and tracking of multiple distinct lineages simultaneously in the same animal [18]. |

| Somatic Mutation Panels (e.g., for DNMT3A, TET2) | Used to identify unique, naturally occurring DNA barcodes that mark expanded clones in human tissue. | Retrospective lineage tracing and clonal contribution analysis in human hematopoiesis [20]. |

| Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus (Mo-MLV) | A retroviral vector that integrates into the host genome only in dividing cells, making it ideal for targeting proliferative populations. | Specific targeting of proliferating reactive glia for direct conversion into neurons in the brain [21]. |

| Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) with Flexed Cassette | A viral vector that can infect non-dividing cells; a double-floxed (FLEX) cassette ensures expression only in Cre-expressing cells. | Requires careful validation, as it can lead to artefactual labeling when used with strong transcriptional activators [21]. |

| Computational Tools (e.g., CellRank 2, STORIES, Clonotrace) | Algorithms that infer cell fate dynamics and trajectories from single-cell omics data without physical labels. | Reconstructing differentiation landscapes and predicting fate biases from snapshot or spatial transcriptomics data [24] [22] [23]. |

The Technological Toolbox: From DNA Barcodes to Live-Cell Imaging

Genetic barcoding has revolutionized stem cell research by enabling precise tracking of individual cells and their progeny over time and space. This powerful approach allows researchers to decipher the complex dynamics of cellular fate, lineage relationships, and clonal dynamics in developing tissues, homeostasis, and disease contexts. As a cornerstone of modern fate mapping techniques, genetic barcoding provides unprecedented insights into the behavior of stem and progenitor cells by marking them with unique, heritable DNA sequences that can be subsequently traced through sequencing-based detection methods [25] [26].

The field has evolved from early methods that relied on visual observation and non-specific dyes to sophisticated molecular technologies capable of simultaneously tracking thousands to millions of clones. Among the most prominent techniques currently employed are retroviral libraries, Polylox barcoding, and transposon tagging, each offering distinct advantages and limitations for specific research applications. These methods have become indispensable tools for understanding stem cell biology, particularly in heterogeneous systems where fate potential and lineage relationships remain incompletely characterized [27] [10].

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these three fundamental genetic barcoding technologies, focusing on their principles, experimental workflows, performance characteristics, and applications in stem cell fate mapping. By synthesizing current methodologies and experimental data, we aim to equip researchers with the information necessary to select the most appropriate barcoding strategy for their specific research questions in stem cell biology and drug development.

Technology Comparison & Performance Data

The table below provides a systematic comparison of the key technical specifications and performance characteristics of retroviral barcoding, Polylox barcoding, and transposon tagging systems:

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Genetic Barcoding Technologies

| Feature | Retroviral Barcoding | Polylox Barcoding | Transposon Tagging |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Introduction of DNA barcodes via viral vector integration | Cre-mediated recombination between loxP sites generates diverse barcodes | Transposase-mediated genomic insertion of DNA sequences |

| Barcode Diversity | High (10⁶-10⁸ with 30bp barcodes) [26] | Very High (theoretical >10⁷) [27] | High (depends on transposon copy number) |

| Integration Mechanism | Semi-random viral integration | Endogenous recombination at defined locus | Semi-random transposition |

| Mutagenesis Risk | Moderate to High (preferential for active genes) [27] | Minimal (defined genomic location) [27] | Moderate (semi-random insertion) [27] |

| In Vivo Applicability | Requires ex vivo transduction & transplantation [27] | Native labeling in situ (transgenic models) [27] | Can be performed in situ with inducible systems [27] |

| Perturbation of Native State | High (transduction + transplantation stress) [27] | Low (minimal system perturbation) [27] | Low to Moderate (depends on delivery method) |

| Lineage Resolution | High (clonal tracking possible) | Very High (single-cell resolution) [27] | High (clonal tracking possible) |

| Single-Cell Compatibility | Yes (with scRNA-seq) | Yes (compatible with scRNA-seq) [27] | Yes (compatible with scRNA-seq) [27] |

| Quantitative Clonal Tracking | Yes (barcode frequency = clonal abundance) | Yes (barcode frequency = clonal abundance) | Yes (integration site = clonal mark) |

| Theoretical Barcode Complexity | 4ⁿ (n=barcode length) [26] | Combinatorial from loxP rearrangements | Limited by transposon diversity |

Table 2: Performance Characteristics in Hematopoietic Stem Cell Tracking

| Performance Metric | Retroviral Barcoding | Polylox Barcoding | Transposon Tagging |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clonal Detection Sensitivity | High (with optimized PCR) | High (with sequencing depth) | Moderate to High |

| Labeling Efficiency | Variable (depends on transduction) | High (in designed models) | Variable (depends on transposition) |

| Long-term Stability | Stable (genomic integration) | Stable (genomic rearrangement) | Stable (genomic integration) |

| Lineage Bias Detection | Yes (through barcode distribution) | Yes (through barcode distribution) | Yes (through integration patterns) |

| Multilineage Reconstitution Analysis | Yes (with lineage sorting) | Yes (with single-cell sequencing) | Yes (with integration site mapping) |

Principles & Experimental Protocols

Retroviral Barcoding

Principle: Retroviral barcoding utilizes lentiviral or γ-retroviral vectors to deliver short, random DNA sequences (typically 20-30 nucleotides) into the genome of target cells. Each unique barcode serves as a heritable mark that can be detected through high-throughput sequencing, enabling quantitative tracking of clonal contributions over time and across different lineages [26] [27]. The semi-random integration pattern of retroviral vectors provides additional clonal marks through integration site analysis, though this approach carries a risk of insertional mutagenesis due to preference for transcriptionally active regions [28] [27].

Experimental Protocol:

- Library Design: Generate a lentiviral library containing 10⁶-10⁸ unique barcode sequences with common PCR priming sites

- Stem Cell Transduction: Transduce hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPCs) at low multiplicity of infection (MOI <0.5) to ensure single barcode integration

- Transplantation: Transplant transduced cells into recipient animals (typically irradiated or immunodeficient mice)

- Time-point Sampling: Collect peripheral blood and bone marrow at multiple time points post-transplantation

- Barcode Recovery: Amplify barcodes from genomic DNA using PCR with library-specific primers

- High-throughput Sequencing: Sequence barcode amplicons to quantify clonal abundances

- Lineage Analysis: Sort specific lineages (myeloid, lymphoid) before barcode recovery to assess lineage bias [27]

Critical Considerations:

- Multiplicity of infection must be optimized to ensure primarily single barcode integration per cell

- Vector design should position barcodes within conserved vector backbone for consistent recovery

- PCR amplification conditions must minimize bias in barcode representation

- Sequencing depth must be sufficient to detect low-abundance clones

Polylox Barcoding

Principle: The Polylox system represents a DNA recombination-based barcoding approach that utilizes Cre-loxP technology to generate diverse barcodes in situ. In engineered mouse models, a transgenic cassette containing multiple loxP sites in alternating orientations is integrated into a defined genomic locus. Upon Cre recombinase activation, stochastic recombination events between loxP sites create unique DNA sequences that serve as heritable barcodes for lineage tracing [27]. This system enables native labeling without transplantation, significantly reducing experimental perturbation.

Experimental Protocol:

- Mouse Model Generation: Create transgenic mice with Polylox cassette containing multiple loxP sites in alternating orientations

- Cre Activation: Cross with tissue-specific or inducible Cre driver lines to activate barcode generation

- Tissue Collection: Harvest tissues of interest at desired time points

- Barcode Amplification: Recover barcodes using PCR with cassette-specific primers

- Sequencing Library Preparation: Prepare sequencing libraries with sample barcodes for multiplexing

- High-throughput Sequencing: Sequence barcode libraries with sufficient depth for clonal detection

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Identify unique barcodes and quantify their abundances across samples

- Single-cell Integration: Combine with single-cell RNA sequencing for multimodal analysis [27]

Critical Considerations:

- Cre efficiency must be optimized for sufficient barcode diversity

- Temporal control of barcode generation can be achieved with inducible Cre systems

- Cassette design determines theoretical barcode diversity and detection reliability

- Background recombination should be monitored in negative controls

Transposon Tagging

Principle: Transposon tagging utilizes mobile genetic elements such as Sleeping Beauty or PiggyBac transposons to integrate marker sequences throughout the genome. The system consists of two components: a transposon vector containing the marker sequence flanked by terminal inverted repeats, and a transposase enzyme that catalyzes excision and reintegration. The quasi-random integration patterns create unique insertion profiles that can serve as clonal markers when mapped to the genome [29] [27]. Recent advancements like TARIS (T7-amplification mediated recovery of integration sites) have improved tag recovery efficiency and reduced amplification bias [27].

Experimental Protocol:

- Transposon Vector Design: Construct transposon vectors with unique molecular tags or barcodes

- Transposase Delivery: Introduce transposase via plasmid transfection, mRNA electroporation, or transgenic expression

- Stem Cell Labeling: Transfer both components to target cells (electroporation or viral delivery)

- Selection: Apply antibiotic selection if vector contains resistance marker

- Transplantation: Transplant labeled cells into recipient animals if studying in vivo reconstitution

- Integration Site Recovery: Use methods like LAM-PCR, TARIS, or nrLAM-PCR to recover integration sites

- Sequencing: Perform high-throughput sequencing of integration sites

- Bioinformatic Mapping: Map sequences to reference genome to identify unique integration sites

- Clonal Tracking: Monitor integration site abundances over time and across lineages [27]

Critical Considerations:

- Transposase activity affects integration efficiency and pattern

- Copy number should be controlled to enable clonal resolution

- Integration bias varies between transposon systems

- Mapping reliability depends on sequencing coverage and genome accessibility

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Genetic Barcoding Applications

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Viral Vectors | Lentiviral barcode libraries, γ-retroviral vectors | Delivery of barcode sequences to target cells |

| Transposon Systems | Sleeping Beauty, PiggyBac transposon/transposase | Genomic integration of marker sequences |

| Site-specific Recombinases | Cre, CreERT2, Dre recombinases | Activation of barcode systems; inducible control |

| Barcode Libraries | Random DNA oligonucleotide pools, Polylox cassettes | Source of diverse barcode sequences |

| Sequencing Adapters | Illumina-compatible adapters, sample barcodes | Preparation of sequencing libraries |

| Cell Sorting Markers | Fluorescent proteins (GFP, RFP), cell surface antigens | Identification and isolation of labeled cells |

| PCR Reagents | High-fidelity polymerases, barcode-specific primers | Amplification of barcode sequences |

| Single-cell RNA-seq Kits | 10x Genomics Chromium, SMART-seq reagents | Combined transcriptomic and barcode analysis |

Comparative Analysis & Research Applications

Each barcoding technology offers distinct advantages for specific research applications in stem cell biology and drug development. Retroviral barcoding provides high diversity and sensitive detection, making it ideal for quantitative studies of clonal dynamics in transplantation settings. However, the requirement for ex vivo manipulation and transplantation introduces significant perturbation to the native stem cell state [27]. Additionally, the semi-random integration pattern raises concerns about insertional mutagenesis, particularly when studying oncogenic transformation or long-term safety [28].

The Polylox system addresses many limitations of viral approaches by enabling in situ barcode generation with minimal system perturbation. This technology excels in fate mapping studies during native development and homeostasis, particularly when combined with single-cell transcriptomic analysis [27]. The main limitations include the requirement for sophisticated mouse models and potential challenges in controlling the timing and efficiency of barcode generation.

Transposon tagging offers a versatile middle ground with reasonable diversity and the potential for in situ application. The Sleeping Beauty system has been particularly valuable for hematopoietic stem cell tracking, especially with improved integration site recovery methods like TARIS that reduce amplification bias [27]. Transposon systems also facilitate stabilization approaches through terminal repeat deletion, addressing concerns about vector remobilization in therapeutic applications [29].

For drug development applications, each technology provides unique insights. Retroviral barcoding enables sensitive tracking of stem cell responses to therapeutic compounds, while Polylox offers a more physiologically relevant model for assessing drug effects on native stem cell populations. Transposon systems balance scalability with genomic safety considerations, making them attractive for preclinical safety assessment of stem cell-based therapies.

Genetic barcoding technologies have fundamentally transformed our ability to interrogate stem cell biology with unprecedented resolution. The complementary strengths of retroviral libraries, Polylox barcoding, and transposon tagging provide researchers with a versatile toolkit for addressing diverse questions in stem cell fate mapping, from basic developmental mechanisms to therapeutic applications.

Selection of the optimal barcoding approach depends on specific research requirements, including whether native or transplant settings are being studied, the required diversity and resolution, technical constraints, and safety considerations. Retroviral barcoding remains the gold standard for sensitive quantitative tracking in transplantation settings, while Polylox excels in physiological fate mapping with minimal perturbation. Transposon tagging offers a balanced approach with flexibility in delivery and application.

As the field advances, integration of these barcoding technologies with multi-omics approaches and computational analysis will continue to enhance our understanding of stem cell biology, ultimately accelerating the development of novel therapeutic strategies for regenerative medicine and cancer treatment.

Reconstructing the developmental trajectories of cells, a process known as lineage tracing, is a fundamental challenge in biology. The core of this endeavor is to understand cells' developmental fates throughout an organism's life, mapping their journey from progenitor cells to specialized descendants and reconstructing these relationships into a lineage tree [30]. For decades, researchers relied on direct observation, dye injection, transplantation, or viral transduction to track cells. However, these methods were limited by scalability, permanence of the marker, and the inability to resolve individual cells in dense tissues [30].

The field was transformed by the ability to introduce permanent, heritable genetic markers—molecular scars—into cells. These scars are passed down to all progeny, creating a readable barcode that records cell division and differentiation history. Early molecular methods used site-specific recombinases like Cre-loxP to generate unique cellular barcodes [30]. The advent of CRISPR-based Lineage Tracing (CbLT) has revolutionized this field by using programmable gene editing to create complex, evolving scar patterns that provide unprecedented resolution for reconstructing lineage relationships [30].

This guide compares the two primary CRISPR-based tools used as molecular scars for fate mapping: the classic CRISPR/Cas9 system, which relies on error-prone repair of DNA double-strand breaks, and more recent DNA Base Editors, which directly chemically alter DNA bases without breaking the DNA backbone. We will objectively compare their performance, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols.

CRISPR/Cas9: Creating Scars via Double-Strand Breaks

The CRISPR/Cas9 system is a bacterial adaptive immune system repurposed for precise genome editing. The system consists of two key components: the Cas9 endonuclease protein and a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) that directs Cas9 to a specific DNA sequence [31] [32]. Upon binding to a target site defined by the sgRNA and an adjacent Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM), Cas9 generates a double-strand break (DSB) in the DNA [33].

In most eukaryotic cells, DSBs are predominantly repaired through the Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) pathway [31]. NHEJ is an error-prone process that often results in small insertions or deletions (indels) at the cut site [33]. These random indels are the "scars" that serve as heritable barcodes for lineage tracing. When a population of cells is engineered with a single sgRNA target site, each initial editing event creates a unique scar. As cells divide and subsequent rounds of editing occur, these scars accumulate, generating a diverse and recordable history of cell divisions [30].

Base Editors: Creating Scars via Direct Chemical Conversion

DNA base editors represent a paradigm shift in CRISPR-based scarring. They do not create double-strand breaks but instead use a catalytically impaired Cas9 (a nickase, nCas9) fused to a deaminase enzyme to directly convert one base into another [34] [32].

Two main classes of base editors are used for lineage tracing:

- Cytosine Base Editors (CBEs): Fuse nCas9 to a cytidine deaminase, converting cytosine (C) to uracil (U), which is later replicated as thymine (T). This results in a C•G to T•A base transition [34] [35].

- Adenine Base Editors (ABEs): Fuse nCas9 to an evolved adenosine deaminase, converting adenine (A) to inosine (I), which is later replicated as guanine (G). This results in an A•T to G•C base transition [34] [36].

For lineage tracing, these precise, programmable base conversions act as the molecular scars. By targeting multiple sites within a synthetic array or endogenous genomic loci, researchers can generate a diverse set of scars without the genetic damage associated with DSBs [30] [35].

Comparative Performance Analysis

The table below summarizes the key technical characteristics of CRISPR/Cas9 and Base Editors when used for lineage tracing.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of CRISPR/Cas9 and Base Editors in Lineage Tracing

| Feature | CRISPR/Cas9 (NHEJ) | Cytosine Base Editor (CBE) | Adenine Base Editor (ABE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Mechanism | DSB → Error-prone NHEJ repair | Direct C to U conversion → T after replication/repair | Direct A to I conversion → G after replication/repair |

| Primary Scar Type | Insertions/Deletions (Indels) | C•G to T•A transition | A•T to G•C transition |

| Editing Outcome | Stochastic and unpredictable | Highly precise and predictable | Highly precise and predictable |

| DSB Formation | Yes (primary mechanism) | No (uses nickase) | No (uses nickase) |

| Theoretical Scar Diversity | Very High (multiple indel types/sizes) | Moderate (limited to transition mutations) | Moderate (limited to transition mutations) |

| Bystander Edits | Not applicable | Common within the editing window [34] | Less common [34] |

| Reported Editing Efficiency | Variable, can be very high | High (>95% in optimal conditions) [35] | High (up to 50-60% for ABE7.10, >99% for ABE8e) [34] |

| Indel Formation at Target | High (intended outcome) | Low (BE4 reduces indels 2.3-fold vs BE3) [34] | Very Low (<1.2%) [34] |

| Typical Editing Window | N/A | Positions 4-8 (BE4max, Spacer-dependent) [35] | Positions 4-7 (ABE7.10), wider for ABE8e [34] |

The table below contextualizes these technologies within specific lineage tracing methodologies, highlighting their practical applications and limitations as revealed in key studies.

Table 2: Comparison of Select Lineage Tracing Methods Utilizing CRISPR/Cas9 and Base Editors

| Method Name | DNA-Editing System | Scar Type / Barcode | Key Application & Finding | Readout | In Vivo? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GESTALT [30] | Cas9 | INDELs | Pioneered large-scale lineage tracing in zebrafish embryos. | Illumina Sequencing | Yes |

| scGESTALT [30] | Cas9 | INDELs | Combined lineage barcoding with single-cell transcriptomics in zebrafish. | scRNA-seq + Illumina | Yes |

| LINNAEUS [30] | Cas9 | INDELs | Lineage tracing in zebrafish to map embryonic origin of blood cells. | scRNA-seq + Illumina | Yes |

| SMALT [30] | Cytidine Deaminase | C-to-T mutations | Lineage tracing in human cells and mice using engineered bacterial cytidine deaminase. | PacBio Long-Read Sequencing | Yes |

| Hwang et al. [30] | Cytidine Deaminase | C-to-T mutations | Lineage tracing in human cells and mice using a similar base-editing approach. | scRNA-seq + Illumina | Yes |

Experimental Protocols for Lineage Tracing

Protocol: CRISPR/Cas9-based Lineage Tracing (e.g., GESTALT/scGESTALT)

This protocol outlines the key steps for a pooled lineage tracing experiment using CRISPR/Cas9 to induce scar-forming indels, based on the GESTALT method [30].

- Design and Clone the Barcode Array: Create a transgenic construct containing multiple (e.g., 9-12) tandemly arranged, unique sgRNA target sites. This array serves as the primary substrate for scar formation. The construct must use a polymerase II (Pol II) promoter for ubiquitous expression in the organism.

- Generate a Transgenic Model: Integrate the barcode array into the genome of a model organism (e.g., zebrafish, mouse) at a defined locus. This creates the founder animal where all cells initially possess the identical, unedited barcode array.

- Induce Scarring via Cas9 Expression: Cross the transgenic barcode-bearing model with a ubiquitous or inducible Cas9-expressing line. The expression of Cas9 during development will lead to stochastic editing (indel formation) at the various target sites within the barcode array in progenitor cells.

- Tissue Harvesting and Single-Cell Preparation: At the desired time point, dissociate tissues of interest into a single-cell suspension.

- Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (for scGESTALT): For methods like scGESTALT, perform droplet-based single-cell RNA sequencing (e.g., 10x Genomics). This captures the transcriptome of individual cells and the lineage barcodes transcribed from the integrated array.

- Barcode Amplification and Analysis: From the single-cell cDNA or bulk genomic DNA, amplify the integrated barcode array using PCR. Analyze the resulting sequences with high-throughput sequencing (Illumina). The unique combination of indels across the target sites in a cell population represents its lineage history.

- Lineage Tree Reconstruction: Use computational tools to cluster cells based on their shared scar patterns. Cells with more similar scar profiles are more closely related and are grouped together on branching lineage trees.

Protocol: Base Editor-based Lineage Tracing (e.g., SMALT)

This protocol describes lineage tracing using a cytidine base editor to create scars via C-to-T mutations, as exemplified by the SMALT (Somatic Mutagenesis for Lineage Tracing) approach [30].

- Design the Target Barcode Locus: Design a genomic locus or transgenic array containing a high density of cytosine (C) bases in a specific sequence context (e.g., TC, for APOBEC-based deaminases) within the editing window of the base editor.

- Generate the Base Editor Model: Create a model organism that expresses both the target barcode locus and the base editor component (e.g., a CBE like BE4max). The base editor can be under a ubiquitous or cell-type-specific promoter.

- Induce Scarring via Base Editing: During development, the base editor will stochastically convert Cs to Ts at the target locus. The absence of DSBs minimizes cell death and potential confounding selective pressures.

- Tissue Harvesting and DNA/RNA Extraction: Harvest tissues at the desired stage. Extract high-quality genomic DNA for bulk analysis or prepare single-cell suspensions for single-cell RNA-seq.

- Long-Read Sequencing of Barcodes: Amplify the target barcode region and sequence it using long-read sequencing technology (PacBio). This is crucial for base editor tracing because it allows for the phasing of multiple C-to-T mutations, determining which specific mutations occurred on the same DNA molecule, thereby defining a unique lineage barcode [30].

- Variant Calling and Phylogenetic Analysis: Identify all C-to-T mutations relative to the unedited reference sequence. Cluster cells based on their shared base substitution profiles to reconstruct phylogenetic lineage trees.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for CRISPR-based Lineage Tracing

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nuclease | Creates DSBs for indel-based scarring. | SpCas9: Most common; requires NGG PAM. SaCas9: Smaller size, good for AAV delivery; requires NNGRRT PAM [32]. |