Stem Cell Therapy Efficacy in Randomized Clinical Trials: A 2025 Landscape Analysis for Research and Development

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the current efficacy and safety data from randomized clinical trials (RCTs) of stem cell therapies.

Stem Cell Therapy Efficacy in Randomized Clinical Trials: A 2025 Landscape Analysis for Research and Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the current efficacy and safety data from randomized clinical trials (RCTs) of stem cell therapies. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the global clinical trial landscape, mechanisms of action, and therapeutic efficacy across various disease domains, including autoimmune diseases, neurological disorders, and organ failure. It critically examines methodological challenges, optimization strategies for cell sourcing and delivery, and the role of advanced imaging in efficacy validation. The review also discusses the transition towards cell-derived products and provides a forward-looking perspective on the future of regenerative medicine, synthesizing key findings to guide future clinical research and therapeutic development.

The Global Landscape and Mechanistic Foundations of Stem Cell Therapy

Stem cell therapy has emerged as a transformative approach in regenerative medicine, offering potential solutions for some of the most challenging autoimmune, cardiovascular, and neurological conditions. The analysis of clinical trial data provides critical insights into the evolution, current status, and future direction of this dynamic field. This comprehensive analysis leverages data from Trialtrove, a premier clinical intelligence database, to examine global trends in stem cell clinical trials from 2006 to 2025. The focus centers on evaluating the efficacy profiles of these therapies across different disease areas based on evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs), which represent the gold standard for therapeutic validation.

Research communities have demonstrated vigorous commitment to studying potential applications across a wide range of diseases, with the past few years witnessing exponential advancement in clinical trials revolving around stem cell-based therapies [1]. By examining nearly two decades of trial data, this analysis identifies patterns in therapeutic focus, geographic distribution, methodological approaches, and efficacy outcomes that are shaping the next generation of stem cell treatments. The findings presented herein offer researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals an evidence-based perspective on the current state and future trajectory of stem cell therapeutics.

Table 1: Global Stem Cell Clinical Trial Overview (2006-2025)

| Analysis Category | Key Findings | Data Source |

|---|---|---|

| Total Trials Analyzed | 1,511 global trials screened; 244 included after eligibility assessment | Trialtrove [2] |

| Trial Phase Distribution | 83.6% in Phase I-II; 16.4% in Phase III | Trialtrove [2] |

| Leading Disease Areas | Crohn's disease (n=85), SLE (n=36), scleroderma (n=32) | Trialtrove [2] |

| Geographic Leadership | U.S. and China leading in trial numbers | Trialtrove [2] |

| Primary Funding Sources | Academic institutions (49.2% of trials) | Trialtrove [2] |

| Therapeutic Mechanisms | Immune modulation, tissue repair via growth factors, anti-infection/anti-proliferative effects | Trialtrove [2] |

The analysis of Trialtrove data reveals a field in transition, with stem cell therapies demonstrating promising efficacy in specific autoimmune and neurological conditions while showing more limited benefits in cardiovascular applications. The predominance of early-phase trials (83.6% in Phase I-II) indicates a technology still in its relative infancy regarding regulatory approval but with substantial research interest [2]. Disease-specific variations in both cell sources and administration routes highlight the tailored approach required for different therapeutic areas.

Beyond the stem cell-specific trends, the broader clinical trial landscape has shown notable shifts in 2024-2025, with a 5.5% increase in Phase I-III trial initiations and particularly strong growth in autoimmune and inflammation studies (17% surge) according to Citeline's Annual Clinical Trials Roundup [3] [4]. This growth occurs amidst changing regional patterns, including China's expanding role in rare disease trials (now representing 47% share) and Europe's rebound in trial activity post-conflict [3].

Therapeutic Area Efficacy Analysis

Autoimmune and Rheumatic Diseases

Table 2: Stem Cell Efficacy in Autoimmune Diseases (Meta-Analysis of 42 RCTs)

| Disease Area | Therapeutic Outcome | Efficacy Measures | Safety Profile |

|---|---|---|---|

| Osteoarthritis (OA) | Significant symptom improvement | VAS: Bone marrow SMD=-0.95; Umbilical cord SMD=-1.25; Adipose tissue SMD=-1.26 [5] | No increased adverse events (RR=1.23, P=0.15) [5] |

| Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) | Significant disease activity reduction | SLEDAI: SMD=-2.32, P=0.0003 [5] | No increased adverse events (RR=0.83, P=0.76) [5] |

| Inflammatory Bowel Disease | Improved clinical efficacy | RR=2.02, P<0.00001 [5] | No increased adverse events (RR=0.99, P=0.96) [5] |

| Multiple Sclerosis | Limited symptom improvement | Not significant [5] | No increased adverse events (RR=1.12, P=0.50) [5] |

| Systemic Sclerosis | Limited symptom improvement | Not significant [5] | Consistent safety profile [5] |

Mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) transplantation has demonstrated particularly promising results for several rheumatic and autoimmune conditions, according to a systematic review and meta-analysis of 42 RCTs involving 2,183 participants [5]. The analysis encompassed rheumatoid arthritis (RA), osteoarthritis (OA), spondyloarthritis, systemic sclerosis arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), inflammatory bowel disease, multiple sclerosis, and primary Sjögren's syndrome (PSS). The findings reveal a differential efficacy profile across conditions, with MSC transplantation demonstrating significant benefits for OA, SLE, and inflammatory bowel disease, while showing more limited impact on multiple sclerosis and systemic sclerosis.

The safety profile across these applications is notably consistent, with no significant increase in adverse events compared to control groups [5]. This safety record, coupled with the immunomodulatory properties of MSCs, positions stem cell therapy as a viable alternative treatment option for autoimmune and rheumatic immune diseases, particularly for conditions that have shown responsiveness in clinical trials. The therapeutic mechanisms primarily involve immunomodulation, tissue repair via growth factors, and anti-infection/anti-proliferative effects [2].

Cardiovascular Diseases

The efficacy profile of stem cell therapy in cardiovascular applications presents a more complex picture. A comprehensive meta-analysis of 48 RCTs examining stem cell preparations in acute myocardial infarction (AMI) found no significant benefit on clinical endpoints including all-cause mortality, recurrent myocardial infarction, severe adverse events, heart failure hospitalization, cancer incidence, or stroke [6]. The risk ratios for these endpoints were 0.73, 0.93, 0.67, 0.79, 0.82, and 0.81 respectively, with none reaching statistical significance.

Despite the lack of impact on clinical endpoints, modest functional improvements were observed in echocardiographic left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), which improved significantly at study end with a mean difference of 2.53% and a difference from baseline of 3.89% [6]. This improvement, however, was characterized by high heterogeneity (I² = 76%), suggesting variable responses across patient populations or methodologies. When assessed via MRI—considered a more precise imaging modality—LVEF showed no significant change at study end but demonstrated a modest improvement from baseline (MD 1.37%) [6].

For advanced heart failure, a systematic review of 27 clinical trials conducted between 2014 and 2024 noted that while various stem cell approaches (including cardiac stem cells, cardiosphere-derived cells, bone marrow-derived mononuclear cells, mesenchymal stem cells, and pluripotent stem cells) have demonstrated clinically acceptable safety profiles, their efficacy varies and has yet to be conclusively confirmed [7]. The field has seen a shift in focus toward the paracrine signaling effects of injected cells rather than direct differentiation and replacement of damaged tissue.

Neurological Applications

Stem cell therapy for ischemic stroke has demonstrated more encouraging results, particularly for long-term functional outcomes. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 13 RCTs involving 872 patients with acute/subacute ischemic stroke found that stem cell transplantation within one month of onset significantly improved functional outcomes at specific timepoints [8]. The primary outcome was measured using the modified Rankin Scale (mRS), where scores of 0-1 represent minimal or no symptoms, and 0-2 represent functional independence.

The analysis revealed that the 1-year incidence of mRS scores 0-1 was significantly higher in the cell-therapy group (45/195) compared to the control group (23/179), with a risk ratio of 1.74 [8]. At the 90-day mark, the incidence of mRS scores 0-2 was also higher in the treatment group. Importantly, stem cell therapy was not associated with increased serious adverse events or mortality, supporting its safety profile in neurological applications [8].

The timing of functional assessment appears crucial in evaluating outcomes, as differences in NIHSS scores became significant only at the 180-day mark, highlighting the importance of longer follow-up periods in stroke trials [8]. These findings suggest that stem cell therapy for acute/subacute ischemic stroke is safe and can improve long-term functional outcomes, though treatment protocols require further standardization.

Methodology and Experimental Protocols

Data Source and Retrieval Methodology

The foundation of this analysis derives from Trialtrove, a comprehensive clinical intelligence database that aggregates data from more than 60,000 trusted sources including clinical trial registries, conference presentations, scientific literature, and regulatory documents [9]. The database provides curated, real-world intelligence on trial design, enrollment timelines, patient populations, endpoints, outcomes, and geographic trends, enabling robust benchmarking and trend analysis.

For the specific analysis of autoimmune disease trials, researchers extracted clinical trial data from 2006-2025 from Trialtrove, applying strict inclusion criteria that restricted the analysis to interventional trials while excluding observational studies, non-autoimmune disease trials, and records with incomplete information [2]. From an initial identification of 1,511 global trials, 244 were included after rigorous screening and cross-referencing, with descriptive statistics used to analyze trial phases, disease types, geographic distribution, funding sources, therapeutic mechanisms, and stem cell sources.

Meta-Analysis Protocol Standards

The efficacy data presented in this analysis primarily derives from systematic reviews and meta-analyses conducted according to PRISMA guidelines and registered in international prospective registers of systematic reviews (PROSPERO) [6] [8] [5]. These analyses employed comprehensive search strategies across multiple databases including PubMed, Embase, Cochrane, Web of Science, and regional databases, without language restrictions.

Statistical analysis typically utilized RevMan software with random-effects models depending on heterogeneity [6] [5]. Measures of effect included risk ratios with 95% confidence intervals for dichotomous variables and mean differences or standardized mean differences for continuous variables. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I² statistic, with values exceeding 50% indicating substantial heterogeneity. Risk of bias was evaluated using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool, with sensitivity analyses conducted to test the robustness of findings.

Endpoint Selection and Standardization

Across the analyzed trials, standardized endpoint selection was critical for meaningful cross-trial comparisons. For cardiovascular trials, primary outcomes typically included all-cause mortality, recurrent myocardial infarction, severe adverse events, hospitalization for heart failure, cancer incidence, and left ventricular ejection fraction [6]. Neurological trials predominantly utilized the modified Rankin Scale for functional outcomes, supplemented by NIH Stroke Scale scores and Barthel Index scores [8]. Autoimmune disease trials employed disease-specific activity indices such as SLEDAI for lupus, VAS for osteoarthritis, and clinical efficacy rates for inflammatory bowel disease [5].

The consistent application of these validated endpoints enables more reliable pooling of data across studies and enhances the statistical power to detect treatment effects in meta-analyses. This methodological standardization is particularly important in stem cell research, where variations in cell sources, preparation methods, administration routes, and patient populations can contribute to significant heterogeneity in outcomes.

Technical and Resource Requirements

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Stem Cell Clinical Trials

| Research Reagent | Function and Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Bone Marrow Aspiration Kits | Source for BMMNCs and MSCs | AMI trials; Autoimmune disease research [6] [5] |

| Cell Separation Media | Isolation of mononuclear cells via density gradient centrifugation | Preparation of BMMNCs for intracoronary administration [6] |

| X VIVO 10 Media | Serum-free cell culture medium for MSC expansion | Clinical-grade cell preparation [6] |

| CD133+ Selection Kits | Immunomagnetic selection of specific progenitor cell populations | Isolation of CD133+ cells for cardiovascular repair [6] |

| Multiple Electrolytes Injection | Vehicle solution for cell suspension and control injections | Placebo preparation in controlled trials [6] |

| Heparinized Saline | Anticoagulant solution for intracoronary cell delivery | Standardized administration in cardiovascular applications [6] |

| Flow Cytometry Antibody Panels | Characterization of cell surface markers (CD105, CD73, CD90, CD45, CD34) | Verification of MSC phenotype per ISCT criteria [5] |

| Cryopreservation Media | Maintenance of cell viability during storage and transport | Logistics management in multicenter trials [9] |

The successful implementation of stem cell clinical trials requires specialized reagents and materials that ensure cell viability, purity, and functional potency. Cell sourcing and characterization represent critical initial steps, with bone marrow aspiration, adipose tissue extraction, or umbilical cord collection serving as primary tissue sources [6] [5]. The International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) defines MSCs by specific criteria including plastic adherence, expression of CD105, CD73, and CD90, and lack of expression of hematopoietic markers, necessitating standardized flow cytometry protocols [5].

The administration route and formulation vary significantly by disease application. Intracoronary injection through balloon catheters is standard for cardiovascular applications, while intravenous infusion is common for systemic autoimmune conditions [6]. Suspension media including heparinized saline, normal saline, and specialized electrolyte solutions serve as both vehicle controls and cell carriers, highlighting their importance in trial design [6]. Dose optimization remains an area of active investigation, with trials exploring ranges from millions to billions of cells depending on the application and cell type.

The analysis of Trialtrove data from 2006-2025 reveals a field characterized by continued innovation and methodological refinement. The differential efficacy profiles across disease areas highlight the importance of target selection, with particularly promising results in autoimmune conditions like SLE, OA, and inflammatory bowel disease, and functional improvement in stroke recovery [8] [5]. In contrast, cardiovascular applications have demonstrated more modest functional benefits without significant impact on major clinical endpoints [6].

Future developments in the field will likely prioritize technological innovation, international collaboration, and precision medicine approaches to address current challenges [2]. The growing trial activity in autoimmune and inflammatory conditions (17% surge according to recent data) indicates shifting research priorities [3]. Additionally, advancements in cell engineering, delivery methods, and patient selection criteria hold potential for enhancing therapeutic efficacy across applications.

The safety profile of stem cell therapies remains consistently acceptable across diverse applications, with no significant increase in adverse events compared to control groups in multiple meta-analyses [6] [8] [5]. This safety record, coupled with promising efficacy in specific indications, supports the continued investigation of stem cell therapies as potential treatment options for conditions with significant unmet medical needs. As the field matures, standardization of protocols, validation of potency assays, and clarification of mechanistic pathways will be critical for advancing from investigational use to standardized clinical application.

Stem Cell Therapy Efficacy in Randomized Clinical Trials Research

Stem cell therapy represents a revolutionary frontier in regenerative medicine, offering potential treatments for a range of debilitating diseases by harnessing the unique properties of stem cells for self-renewal, multilineage differentiation, and immunomodulation [10]. The therapeutic potential of various stem cell types, including mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), neural stem cells (NSCs), and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), has been explored across diverse medical conditions [11]. This review systematically evaluates the efficacy of stem cell therapies for autoimmune, neurological, and metabolic conditions within the framework of randomized controlled trials (RCTs), providing evidence-based comparisons to guide researchers and drug development professionals. We synthesize quantitative data from recent meta-analyses and clinical trials, detail experimental methodologies, and visualize key mechanistic pathways to offer a comprehensive assessment of the current landscape.

Analysis of Disease Targets

Autoimmune Diseases

Autoimmune diseases, characterized by immune dysregulation and chronic inflammation, represent a major focus of stem cell therapy research. Current therapies often lack sustained efficacy and safety, necessitating alternative approaches [12].

- Clinical Trial Landscape: A systematic review of global clinical trials from 2006 to 2025 identified 244 interventional trials focusing on stem cell therapy for autoimmune diseases. The most frequently studied conditions were Crohn's disease (n=85), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE, n=36), and scleroderma (n=32). The majority (83.6%) of these trials were in early phases (Phase I-II), with the United States and China leading in trial numbers [12].

- Efficacy of MSC Transplantation: A 2025 meta-analysis of 42 RCTs involving 2,183 participants provided robust evidence for the efficacy of MSC transplantation in specific autoimmune and rheumatic diseases [5]. The analysis demonstrated significant symptom improvement in several conditions, while revealing limited benefits in others.

Table 1: Efficacy of Mesenchymal Stem Cell (MSC) Transplantation in Autoimmune and Rheumatic Diseases (Meta-Analysis of RCTs)

| Disease | Outcome Measure | Effect Size [95% CI] | P-value | Source Tissue |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Osteoarthritis (OA) | VAS Pain Score | SMD = -1.25 [-2.04 to -0.46] | 0.002 | Umbilical Cord [5] |

| Osteoarthritis (OA) | VAS Pain Score | SMD = -1.26 [-1.99 to -0.52] | 0.0009 | Adipose Tissue [5] |

| Osteoarthritis (OA) | VAS Pain Score | SMD = -0.95 [-1.55 to -0.36] | 0.002 | Bone Marrow [5] |

| Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) | SLEDAI Disease Activity | SMD = -2.32 [-3.59 to -1.06] | 0.0003 | Not Specified [5] |

| Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) | Clinical Efficacy | RR = 2.02 [1.53 to 2.67] | < 0.00001 | Not Specified [5] |

| Multiple Sclerosis | Symptom Improvement | Not Significant | - | Not Specified [5] |

| Systemic Sclerosis | Symptom Improvement | Not Significant | - | Not Specified [5] |

Abbreviations: CI, Confidence Interval; RR, Risk Ratio; SMD, Standardized Mean Difference; SLEDAI, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale.

- Safety Profile: The same meta-analysis confirmed the safety of MSC transplantation, finding no significant increase in the incidence of adverse events across studies for osteoarthritis, SLE, inflammatory bowel disease, and multiple sclerosis [5].

Neurological Diseases

Ischemic Stroke

Stem cell therapy has been investigated as a means to promote repair and regeneration following ischemic stroke, a leading cause of global disability and mortality [13].

- Efficacy on Functional Outcomes: A 2025 meta-analysis of 13 RCTs involving 872 patients with acute/subacute ischemic stroke evaluated the long-term efficacy of stem cell therapy administered within one month of onset [8]. The analysis revealed significant improvements in functional independence, particularly at long-term follow-up.

- The primary outcome, the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score (where 0-1 indicates excellent functional outcome), showed a significantly higher incidence in the cell-therapy group at 1 year (45/195 vs. 23/179 in controls; RR=1.74, 95% CI 1.09-2.77) [8].

- At 90 days, the incidence of mRS scores 0-2 (functional independence) was also higher in the cell-therapy group (RR=1.31, 95% CI 1.01-1.70) [8].

- Safety: The therapy was not associated with an increased incidence of serious adverse events or mortality, supporting its safety profile in stroke patients [8].

Neurodegenerative Diseases

For chronic neurodegenerative diseases (NDs) like Alzheimer's disease (AD), Parkinson's disease (PD), Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), and Huntington's disease (HD), stem cell therapy aims to replace lost neurons and modulate the disease environment [14].

- Clinical Trial Landscape: A systematic review identified 94 clinical trials for these four NDs. The field is predominantly in early stages, with only three Phase 3 trials identified (one each for ALS and HD completed, and one ongoing in ALS). Over 8,000 participants have been enrolled, with nearly 70% in AD-related studies [14].

- Promising Alternatives: Stem cell-derived exosomes have emerged as a promising cell-free alternative. These nanovesicles can cross the blood-brain barrier more efficiently than stem cells, deliver therapeutic molecules directly to the brain, and exhibit a reduced risk of immunological rejection and tumorigenicity. While most research is preclinical, clinical investigations are anticipated to increase [14].

Metabolic Diseases

The search results indicate a comparative lack of recent, high-level meta-analyses or systematic reviews focusing specifically on stem cell therapy for metabolic conditions like diabetes mellitus within the provided data. While one review mentions the "unprecedented therapeutic opportunities" for a range of conditions including diabetes, it does not provide specific efficacy data from clinical trials [11]. Another review on heart failure, which can have metabolic components, notes that stem cell therapies have demonstrated clinically acceptable safety profiles but that their efficacy "varies and has yet to be conclusively confirmed" [7]. This highlights a significant area for future targeted clinical research.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The validity of RCT findings hinges on rigorous and standardized experimental protocols. This section details methodologies commonly employed in the cited trials.

Trial Design and Patient Selection

The highest quality evidence comes from RCTs that adhere to strict guidelines.

- Registration and Protocol: Trials should be pre-registered in databases like ClinicalTrials.gov, and follow published protocols (e.g., on PROSPERO for systematic reviews) [5] [8].

- Participants: Participants must meet recognized diagnostic criteria for the target disease (e.g., the American College of Rheumatology criteria for rheumatoid arthritis or standardized stroke diagnosis) [5] [8].

- Intervention and Control: The experimental group receives the stem cell product (e.g., MSCs from various sources), while the control group receives a placebo, conventional therapy, or standard care [5] [8].

- Outcomes: Primary and secondary outcomes are defined a priori. These are often disease-specific functional scores, such as the mRS for stroke, SLEDAI for SLE, or VAS for pain in osteoarthritis [5] [8].

Stem Cell Preparation and Characterization

The process of preparing the cellular product is critical for consistency and safety.

- Source and Isolation: MSCs are isolated from tissues like bone marrow, adipose tissue, or umbilical cord via enzymatic digestion or density gradient centrifugation. iPSCs are generated by reprogramming somatic cells [11] [10].

- Characterization: According to International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) standards, MSCs must be adherent to plastic; express surface markers CD105, CD73, and CD90 (≥95%); lack expression of hematopoietic markers CD45, CD34, CD14, CD11b, CD79α, CD19, and HLA-DR (≤2%); and possess the capacity to differentiate into osteoblasts, adipocytes, and chondrocytes in vitro [10].

- Quality Control: Tests for viability, sterility (mycoplasma, bacteria, fungi), and potency are essential before clinical administration.

Administration and Follow-up

- Route of Administration: This varies by disease target. Common routes include intravenous (IV) infusion, intra-arterial injection, intrathecal injection, or direct implantation into the target tissue [13] [14].

- Dosing and Timing: Trials investigate optimal cell doses (e.g., 1-2 million cells per kg body weight) and the ideal therapeutic time window (e.g., within 36 hours for acute stroke vs. chronic phase for neurodegenerative diseases) [13] [8].

- Follow-up and Monitoring: Patients are followed for extended periods (e.g., 1-5 years) to assess both primary efficacy outcomes and long-term safety, including monitoring for adverse events and potential tumorigenicity [5] [8].

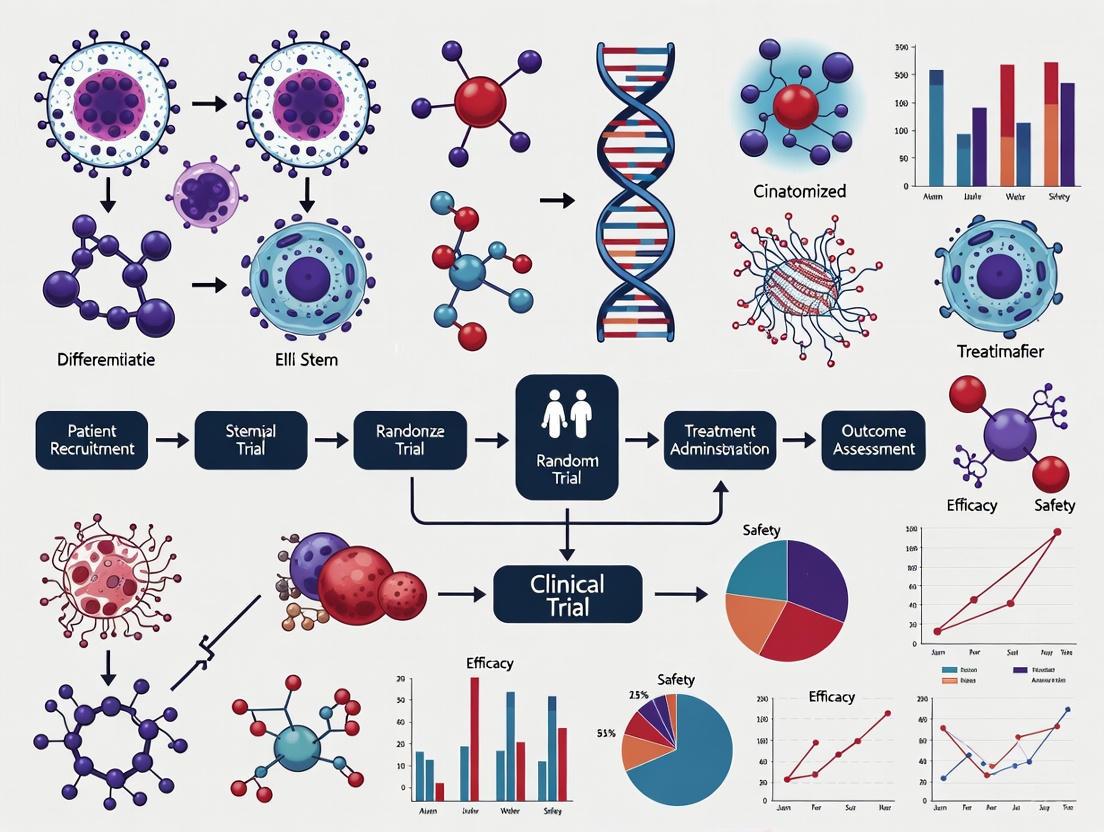

Visualization of Key Mechanisms

The therapeutic effects of stem cells, particularly MSCs, are mediated through multiple interconnected mechanisms. The following diagram illustrates the primary pathways through which MSCs exert their therapeutic effects in autoimmune and neurological diseases.

Diagram 1: Key Therapeutic Mechanisms of Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs). MSCs mediate their effects primarily through paracrine signaling of bioactive molecules, immunomodulation via interactions with diverse immune cells, and direct repair mechanisms including mitochondrial transfer and differentiation. VEGF: Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor; HGF: Hepatocyte Growth Factor; Tregs: Regulatory T-cells.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for conducting preclinical and clinical research in stem cell therapy.

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Stem Cell Therapy Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture Media | Supports the growth, expansion, and maintenance of stem cells in vitro. | Defined media (e.g., DMEM/F12) supplemented with growth factors like FGF-2 for MSC expansion; TeSR-E8 for pluripotent stem cells. |

| Characterization Antibodies | Flow cytometry analysis to confirm stem cell identity based on surface marker expression. | Anti-CD105, Anti-CD73, Anti-CD90 (positive markers); Anti-CD45, Anti-CD34, Anti-HLA-DR (negative markers for MSCs) [10]. |

| Differentiation Kits | Induces stem cell differentiation into specific lineages to confirm multipotency. | Osteogenic, adipogenic, and chondrogenic differentiation kits (e.g., containing dexamethasone, ascorbate, insulin, TGF-β3) [10]. |

| Extracellular Vesicle Isolation Kits | Isolates exosomes and other EVs from stem cell culture supernatants for mechanistic studies or therapeutic use. | Polymer-based precipitation kits, size-exclusion chromatography columns, or tangential flow filtration systems. |

| Animal Disease Models | Preclinical testing of stem cell therapy safety and efficacy. | Transgenic mouse models of AD/PD, Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion (MCAO) model for stroke, collagen-induced arthritis model. |

| In Vivo Imaging Systems | Tracks the biodistribution, persistence, and fate of transplanted cells in live animals. | Bioluminescence (BLI) and Fluorescence (FLI) imaging systems; MRI for anatomical and functional assessment [13]. |

This comparison guide synthesizes current evidence from randomized clinical trials on stem cell therapy for autoimmune, neurological, and metabolic conditions. The data demonstrates a promising yet nuanced picture: stem cell therapy, particularly using MSCs, shows significant efficacy and a favorable safety profile in specific autoimmune diseases like SLE, OA, and IBD, as well as in improving long-term functional outcomes after ischemic stroke. In contrast, the evidence for its application in neurodegenerative diseases is still in earlier phases of clinical validation, and robust data for metabolic diseases remains limited. The field is rapidly evolving with the emergence of innovative approaches such as stem cell-derived exosomes and engineered iPSCs, which may address current challenges related to tumorigenicity and poor cell integration. Future progress will depend on standardizing treatment protocols, conducting larger Phase III trials, and leveraging advanced imaging and 'omics' technologies to better understand therapeutic mechanisms and identify responsive patient populations.

Stem cell therapies have emerged as a transformative approach in regenerative medicine, demonstrating significant potential in treating conditions ranging from degenerative diseases to hematologic disorders and organ failure. Within the clinical trial landscape, three stem cell types have garnered predominant focus: Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs), valued for their immunomodulatory properties and tissue repair capabilities; Pluripotent Stem Cells (PSCs), including induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and embryonic stem cells (ESCs), prized for their unlimited differentiation potential; and Hematopoietic Stem Cells (HSCs), the workhorse of established transplant medicine for blood and immune system reconstitution [10] [15]. The therapeutic application of these cells hinges on their unique biological properties—MSCs act largely through paracrine signaling and immunomodulation, PSCs offer potential for cell replacement through their pluripotency, and HSCs provide curative potential for hematologic diseases through direct engraftment and differentiation [10] [16]. This review systematically compares the efficacy, safety, and clinical applications of these key stem cell types based on current clinical trial evidence, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a data-driven analysis of their respective positions in modern medicine.

Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs): The Immunomodulatory Workhorse

Biological Properties and Clinical Mechanisms

Mesenchymal stem cells are multipotent stromal cells characterized by their capacity for self-renewal and differentiation into mesodermal lineages including osteoblasts, chondrocytes, and adipocytes [10]. According to International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) standards, MSCs must express specific surface markers (CD73, CD90, and CD105 ≥95%) while lacking expression of hematopoietic markers (CD34, CD45, CD14 or CD11b, CD79α or CD19, HLA-DR ≤2%) [10]. The therapeutic effects of MSCs are mediated primarily through paracrine mechanisms rather than direct differentiation, releasing bioactive molecules including growth factors, cytokines, and extracellular vesicles that modulate the local cellular environment, promote tissue repair, angiogenesis, and exert anti-inflammatory effects [10] [7]. MSCs additionally interact with various immune cells—including T cells, B cells, dendritic cells, and macrophages—modulating immune responses through both direct cell-cell contacts and release of immunoregulatory molecules [10].

MSCs are isolated from multiple tissue sources, each with distinct functional characteristics:

- Bone Marrow-derived MSCs (BM-MSCs): The most extensively studied type, known for high differentiation potential and strong immunomodulatory effects [10]

- Adipose-derived MSCs (AD-MSCs): Easier to harvest in greater quantities with comparable therapeutic properties [10]

- Umbilical Cord-derived MSCs (UC-MSCs): Exhibit enhanced proliferation capacity and lower immunogenicity, suitable for allogeneic transplantation [10]

A 2024 meta-analysis directly compared these sources for knee osteoarthritis treatment, with functional improvement assessed via WOMAC scores and pain relief via VAS scores [17]. The following table summarizes the comparative efficacy data:

Table 1: Comparative Efficacy of MSC Sources in Knee Osteoarthritis (6-month follow-up)

| Outcome Measure | BM-MSC vs. AD-MSC (MD, 95% CI) | BM-MSC vs. UC-MSC (MD, 95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| WOMAC Total | -20.12 (-125.24 to 42.88) | -7.81 (-158.13 to 74.99) |

| WOMAC Stiffness | -0.51 (-7.27 to 4.29) | -0.75 (-9.74 to 6.63) |

| WOMAC Functional Limitation | -12.22 (-35.05 to 18.86) | -9.31 (-44.26 to 35.27) |

| WOMAC Pain | -11.42 (-39.52 to 11.77) | -6.73 (-47.36 to 29.15) |

MD: Mean Difference; CI: Confidence Interval [17]

While most differences were not statistically significant, the meta-analysis concluded that BM-MSCs may present clinical advantages over other MSC sources for functional improvement, with BM-MSCs and UC-MSCs potentially offering superior pain relief compared to AD-MSCs [17].

Experimental Protocols in MSC Clinical Trials

Standardized protocols for MSC isolation, expansion, and characterization are critical for clinical trial reproducibility. Typical manufacturing processes include:

- Isolation: Mononuclear cell separation via density gradient centrifugation from bone marrow aspirate, adipose tissue digestion, or umbilical cord extraction

- Expansion: Culture in serum-free media supplemented with growth factors (primarily FGF-2) under strict Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) conditions

- Characterization: Flow cytometry verification of surface marker expression (≥95% positive for CD73, CD90, CD105; ≤2% positive for hematopoietic markers) and differentiation assays into osteogenic, chondrogenic, and adipogenic lineages [10]

For osteoarthritis trials referenced in Table 1, the typical intervention involved single intra-articular injections of 10-100×10^6 MSCs, with efficacy outcomes measured at 6 and 12 months using standardized scoring systems (WOMAC, VAS) [17].

Figure 1: MSC Clinical Trial Workflow from cell isolation to outcome assessment

Pluripotent Stem Cells: The Differentiative Powerhouses

Biological Properties and Clinical Transition

Pluripotent stem cells, comprising both embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), are defined by their capacity for unlimited self-renewal and ability to differentiate into derivatives of all three germ layers [15]. While ESCs originate from the inner cell mass of blastocysts, iPSCs are generated through reprogramming of somatic cells by introducing specific transcription factors (OCT4, SOX2, c-MYC, and KLF4) [18] [15]. iPSCs have emerged as particularly promising due to their avoidance of ethical concerns associated with ESCs and their potential for patient-specific therapies, though most current clinical applications favor allogeneic approaches [19] [15].

The clinical transition of PSC-based therapies has accelerated remarkably. According to the Human Pluripotent Stem Cell Registry (hPSCreg) database, since 2018 there has been a definitive switch toward iPSCs, with allogeneic approaches dominating over personalized medicines [19]. As of 2023, 109 clinical studies using PSCs were recorded, targeting 44 different diseases across 14 countries [19].

Clinical Applications and Trial Outcomes

PSC-derived therapies have diversified significantly, with 22 different cell types now used in clinical trials. The most frequent applications include:

- Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells: Used in 22 clinical trials for degenerative eye diseases such as age-related macular degeneration

- NK Cell-like Derivatives: Employed in 18 clinical studies, predominantly initiated within the last five years, many incorporating chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) for cancer immunotherapy

- Cardiomyocyte-like Cells: Applied in 12 studies targeting heart failure through direct myocardial regeneration

- Tissue-Specific Stem Cells/MSC-like Cells: Utilized in 12 trials leveraging their immunomodulatory properties for diverse disease targets [19]

Table 2: Current Clinical Applications of PSC-Derived Cell Therapies

| Cell Type | Number of Trials | Primary Indications | Notable Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells | 22 | Degenerative eye diseases | Most established application; multiple phase II/III trials |

| NK Cell-like Derivatives | 18 | Liquid and solid tumors | Often CAR-modified; predominantly industry-sponsored |

| Cardiomyocyte-like Cells | 12 | Heart failure | Addressing myocardial regeneration; safety established |

| Tissue-Specific Stem Cells | 12 | Diverse inflammatory/autoimmune conditions | Immunomodulatory properties; multiple mechanisms |

While comprehensive efficacy data from phase III trials remains limited, the safety profile of PSC-derived therapies has been generally acceptable across applications [19] [7]. Study durations range from 1 to 19 years (median 7 years), reflecting the long-term follow-up required for these novel interventions [19].

Experimental Protocols and Manufacturing

Critical to PSC clinical translation is robust differentiation protocols and manufacturing:

- Reprogramming: For iPSCs, somatic cells (typically dermal fibroblasts) are reprogrammed using non-integrating Sendai virus or episomal vectors expressing OCT4, SOX2, c-MYC, and KLF4 [18]

- Differentiation: Directed differentiation using stage-specific growth factors and small molecules—for example, retinal pigment epithelial cells via dual SMAD inhibition, cardiomyocytes through Wnt modulation

- Purification: Cell sorting for specific surface markers or metabolic selection to eliminate undifferentiated pluripotent cells

- Quality Control: Karyotyping, pluripotency confirmation, and teratoma formation assays to ensure genetic stability and prevent tumorigenicity [19] [18]

The field faces standardization challenges, with most clinical trials not publicly disclosing the specific PSC lines used—only 11 ESC lines and 1 iPSC line could be traced across all registered trials [19].

Figure 2: PSC differentiation and therapeutic application workflow

Hematopoietic Stem Cells: The Established Curative Modality

Biological Properties and Clinical Applications

Hematopoietic stem cells are multipotent stem cells responsible for lifelong production of all blood cell lineages, residing primarily in bone marrow but mobilizable to peripheral blood and present in umbilical cord blood [20] [16]. HSCs are characterized by surface markers CD34+, CD59+, CD90+, CD38-, and CD45RA-, though clinical transplantation typically uses heterogeneous populations containing HSCs [16]. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) represents the most established stem cell therapy, offering curative potential for various hematologic disorders, immune deficiencies, and genetic diseases through complete reconstitution of the recipient's hematopoietic system [20] [16].

Efficacy and Safety Outcomes Across Indications

Substantial clinical trial data supports HSCT efficacy across conditions:

- Sickle Cell Disease (SCD): A 2025 meta-analysis of 58 studies (n=7,931) demonstrated 94% overall survival (OS) and 86% event-free survival (EFS) post-allo-HSCT, with graft failure (GF) at 9% and mortality at 6% [16]

- Hepatitis-Associated Aplastic Anemia (HAAA): A 2023 retrospective analysis comparing immunosuppressive therapy (IST) with HSCT showed 5-year OS of 83.7±4.9% for IST versus 93.3±6.4% for matched-sibling donor HSCT and 80.8±12.3% for haploidentical-HSCT [20]

- Hematologic Response Rates: HSCT recipients exhibited significantly more rapid and sustained hematopoiesis than IST (HR 76.92%, 96.15% and 96.15% at 3, 6 and 12 months, respectively, versus 55.71% at 6 months for IST) [20]

Table 3: Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Outcomes Across Indications

| Condition | Study Scale | Overall Survival | Event-Free Survival | Graft Failure | Key Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sickle Cell Disease | 58 studies (n=7,931) | 94% | 86% | 9% | aGVHD (20%), cGVHD (14%) |

| HAAA (MSD-HSCT) | Single-center (n=26) | 93.3±6.4% (5-year) | 93.3±6.4% (5-year) | Not specified | Infection, GVHD |

| HAAA (IST) | Single-center (n=70) | 83.7±4.9% (5-year) | 64.3±6.0% (5-year) | Not applicable | Relapse, clonal evolution |

Subgroup analyses demonstrate that clinical outcomes vary significantly based on donor type (matched sibling donor vs. haploidentical), conditioning regimens (myeloablative vs. reduced intensity), and stem cell sources (bone marrow vs. peripheral blood vs. cord blood) [20] [16]. Personalized conditioning regimens and post-transplantation prophylaxis strategies are critical for minimizing graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and graft failure issues [16].

Experimental Protocols in HSCT Trials

Standardized HSCT protocols include:

- Conditioning Regimens: Myeloablative (e.g., busulfan/cyclophosphamide) or reduced-intensity (e.g., fludarabine-based) regimens to eliminate recipient immune system and create niche space

- Stem Cell Source: Bone marrow harvest, peripheral blood apheresis after mobilization, or umbilical cord blood unit selection

- GVHD Prophylaxis: Calcineurin inhibitors (cyclosporine, tacrolimus) with methotrexate or mycophenolate mofetil

- Engraftment Monitoring: Daily complete blood counts with neutrophil engraftment defined as first of three consecutive days with ANC >500/μL, platelet engraftment as first of seven consecutive days with platelets >20,000/μL without transfusion [20]

For HAAA trials, the FAC conditioning regimen composed of fludarabine (30 mg/m²/d, days -5 to -1), cyclophosphamide (30 mg/kg/d or 37.5 mg/kg/d, days -5 to -2), and anti-thymocyte globulin has demonstrated efficacy with acceptable toxicity [20].

Comparative Analysis: Efficacy, Safety and Applications

Cross-Category Efficacy and Safety Profiles

Direct comparison of the three stem cell categories reveals distinct efficacy and safety profiles:

- Therapeutic Mechanisms: MSCs function predominantly through paracrine signaling and immunomodulation; PSCs through targeted cell replacement; HSCs through complete hematopoietic system reconstitution [10] [16] [15]

- Efficacy Timeframes: MSC effects typically manifest within months; PSC-derived therapies may require longer integration; HSCs demonstrate rapid hematologic reconstitution within weeks [17] [20] [19]

- Safety Considerations: MSCs exhibit excellent safety profiles with minimal adverse events; PSCs carry theoretical tumorigenicity risks from residual undifferentiated cells; HSCs face significant risks including GVHD, graft failure, and conditioning regimen toxicities [17] [19] [16]

Notably, MSC therapy for acute/ subacute ischemic stroke demonstrated significantly improved 1-year functional outcomes (mRS scores 0-1: 45/195 cell therapy vs. 23/179 control; RR=1.74, 95% CI=1.09-2.77) without increased serious adverse events [8]. Similarly, stem cell therapy for acute myocardial infarction showed a favourable safety profile with significant long-term improvement in left ventricular ejection fraction (mean difference 2.63%, 95% CI 0.50% to 4.76%, p=0.02) [21].

Regulatory and Manufacturing Considerations

Regulatory frameworks significantly influence stem cell therapy development globally:

- United States: Flexible approach with prior notification model for clinical trials and Accelerated Approval pathway potential [15]

- European Union & Switzerland: Rigorous regulations requiring manufacturing licenses and prior authorization for clinical trials [15]

- Japan & South Korea: Balanced approaches incorporating elements from both regulatory regimes with strong national funding programs [15]

Manufacturing challenges vary substantially—MSCs require expansion while maintaining functionality; PSCs need complex differentiation protocols and rigorous safety testing; HSCs require careful donor matching and cell processing [10] [19] [16]. The trend toward allogeneic "off-the-shelf" products is evident across all categories, though most advanced in HSCs [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Stem Cell Clinical Trial Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Marker Antibodies | CD73, CD90, CD105, CD34, CD45, CD14, CD19, HLA-DR | Cell population characterization and purity assessment | Critical for ISCT compliance for MSCs; CD34 for HSCs [10] |

| Cytokines & Growth Factors | FGF-2, SCF, TPO, IL-6, BMP-4, Activin A, VEGF | Maintenance, expansion, and directed differentiation | FGF-2 essential for MSC expansion; specific combinations for PSC differentiation [10] [18] |

| Cell Culture Media | Serum-free MSC media, mTeSR1, StemSpan | Maintenance of stemness and proliferation | Defined, xeno-free formulations required for clinical applications [18] |

| Reprogramming Factors | OCT4, SOX2, c-MYC, KLF4 | iPSC generation from somatic cells | Non-integrating delivery systems preferred for clinical applications [18] [15] |

| Characterization Assays | Teratoma formation, trilineage differentiation, karyotyping | Safety and functionality assessment | Mandatory for PSC-derived products; differentiation capacity for MSCs [19] |

The clinical trial landscape for stem cell therapies continues to evolve, with each major category finding its distinctive therapeutic niche. MSCs demonstrate robust safety and efficacy in immunomodulatory and tissue repair contexts, particularly for orthopedic, inflammatory, and neurological conditions. PSCs offer unprecedented potential for cell replacement therapies, with ongoing innovation in manufacturing and safety protocols needed to fully realize their clinical potential. HSCs remain the gold standard for curative intent in hematologic diseases, with continuing refinements in donor selection, conditioning regimens, and supportive care improving outcomes.

Future progress will depend on addressing key challenges: standardization of manufacturing protocols and potency assays, development of more predictive preclinical models, implementation of harmonized regulatory standards across jurisdictions, and execution of well-powered late-stage clinical trials with standardized endpoints. As the field matures, combination approaches leveraging the strengths of multiple stem cell types may offer synergistic benefits, potentially representing the next frontier in regenerative medicine.

Stem cell therapy has emerged as a transformative approach in regenerative medicine, with its therapeutic potential demonstrated across a spectrum of human diseases including cardiovascular, neurological, and autoimmune conditions [10]. The efficacy of these therapies in randomized clinical trials (RCTs) is fundamentally underpinned by three core biological mechanisms: immune modulation, paracrine signaling, and direct tissue repair. Rather than operating in isolation, these mechanisms function as an integrated system where stem cells respond to inflammatory cues in damaged tissues, subsequently releasing a complex portfolio of bioactive molecules that coordinate repair processes [22] [23] [10]. This guide provides a systematic comparison of these mechanisms across different stem cell types, with detailed experimental data and methodologies to inform research and drug development.

Table 1: Core Therapeutic Mechanisms of Stem Cells

| Mechanism | Key Effectors | Primary Biological Outcomes | Evidence Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immune Modulation | IDO, PGE2, HLA-G5, IL-10, TGF-β, TSG-6, PD-L1 [22] [10] [24] | Suppression of T-cell proliferation, macrophage polarization to anti-inflammatory phenotype, Treg induction [10] [24] | Multiple RCTs across autoimmune diseases and inflammatory disorders [10] |

| Paracrine Signaling | VEGF, HGF, FGF, Sfrp2, HASF, microRNAs, EVs [23] [10] | Angiogenesis, cardiomyocyte protection, reduced apoptosis, tissue remodeling [23] | Preclinical models and secondary outcomes in cardiovascular RCTs [21] [23] |

| Tissue Repair & Differentiation | Direct differentiation, cell-cell contact, ECM protein secretion [10] | Replacement of damaged cardiomyocytes, neurons, cartilage; structural restoration [10] | Limited human evidence; primarily preclinical observations [10] |

Immune Modulation: Mechanisms and Experimental Evidence

The immunomodulatory capabilities of stem cells, particularly mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (MSCs), represent one of the most rigorously validated mechanisms in clinical research. These cells function as "signal-responsive regulators" that sense inflammatory environments and deploy sophisticated immunosuppressive responses [22] [10].

Molecular Effectors and Mechanisms

MSCs modulate both innate and adaptive immunity through multiple molecular pathways. When licensed by pro-inflammatory cytokines like interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-β1), MSCs significantly upregulate indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), which metabolizes tryptophan and suppresses T-cell proliferation [10] [24]. They also express prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), which inhibits macrophage production of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) while enhancing IL-10 secretion [24]. Additional mediators include HLA-G5, which inhibits T-cell and antigen-presenting cell function, and programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), which induces T-cell anergy and apoptosis [22] [10].

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Immune Modulation

PBMC Co-culture Assay for T-cell Modulation:

- Objective: Quantify MSC-mediated suppression of T-cell proliferation and regulatory T-cell (Treg) induction [24].

- Methodology: Isolate PBMCs from healthy donors using Ficoll density gradient centrifugation. Label PBMCs with cell proliferation dyes (e.g., CFSE). Co-culture activated PBMCs with MSCs or MSC-derived extracellular vesicles (EVs) at varying ratios (e.g., 10:1 PBMC:MSC) for 3-5 days. Assess T-cell proliferation via flow cytometry measuring CFSE dilution and quantify Treg population (CD4+CD25+FOXP3+) using specific surface and intracellular staining [24].

- Key Measurements: Percentage inhibition of T-cell proliferation, fold-increase in Treg population, cytokine profiling (IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-10) via ELISA or multiplex assays.

Macrophage Polarization Assay:

- Objective: Evaluate MSC-induced shift from pro-inflammatory (M1) to anti-inflammatory (M2) macrophage phenotype [24].

- Methodology: Differentiate human THP-1 monocytic cells into macrophages using phorbol esters. Polarize toward M1 phenotype using lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and IFN-γ. Treat with MSC-conditioned medium or EVs for 24-48 hours. Analyze surface markers (CD80, CD86 for M1; CD206, CD163 for M2) via flow cytometry and measure cytokine secretion (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-10) [24].

- Key Measurements: M1/M2 marker expression ratios, pro- vs anti-inflammatory cytokine ratios, nitric oxide production.

Comparative Efficacy Across Cell Types

Table 2: Immunomodulatory Efficacy Across Stem Cell Types

| Stem Cell Type | Key Strengths | Limitations | Clinical Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bone Marrow MSCs | Strong T-cell suppression, enhanced IDO expression following licensing [10] [24] | Invasive harvesting, donor age-dependent effects [10] | Phase III trials in GvHD; 85% success in autoimmune disease treatment [10] [25] |

| Adipose-Derived MSCs | Abundant tissue source, potent TSG-6 secretion, anti-fibrotic effects [26] [10] | Variable cell yields based on processing methods [10] | Advanced phase trials for Crohn's disease and rheumatoid arthritis [26] [10] |

| Umbilical Cord MSCs | High proliferation capacity, low immunogenicity, superior EV production [10] | Limited donor availability, ethical considerations in some regions [10] | Promising results in COVID-19 ARDS and neurodegenerative conditions [10] |

| Embryonic Stem Cells | Pluripotency, theoretically unlimited expansion capacity [10] | Ethical controversies, teratoma risk, requires differentiation prior to use [10] [7] | Limited clinical application due to safety and ethical concerns [10] [7] |

Paracrine Signaling: Secreted Factors as Primary Mediators

Paracrine signaling has emerged as the predominant mechanism explaining stem cell efficacy in many clinical contexts, whereby stem cells release bioactive molecules that orchestrate tissue repair without significant long-term engraftment [23] [10].

Key Paracrine Factors and Functions

Stem cells secrete a diverse array of factors with distinct therapeutic functions. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) stimulate angiogenesis, creating new blood vessels to support damaged tissues [23]. Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) promotes tissue regeneration and possesses anti-fibrotic properties [23]. The secreted frizzled-related protein 2 (Sfrp2) and hypoxic induced Akt regulated stem cell factor (HASF) provide crucial cardioprotection by reducing cardiomyocyte apoptosis through mitochondrial death pathway modulation [23]. Additionally, extracellular vesicles (EVs) containing microRNAs, proteins, and lipids mediate intercellular communication and transfer of bioactive components [10] [24].

Experimental Protocols for Paracrine Analysis

Conditioned Media Collection and Concentration:

- Objective: Generate cell-free therapeutic material for mechanistic studies [23] [24].

- Methodology: Culture MSCs to 70-80% confluence. Replace with serum-free medium to eliminate confounding factors. After 24-48 hours, collect conditioned medium and concentrate using centrifugal filter devices (e.g., 3-10 kDa cutoff). Analyze protein content via proteomic approaches or target-specific ELISAs [23].

- Key Applications: In vitro cytoprotection assays, angiogenesis assays, in vivo testing of cell-free therapeutics.

Tube Formation Assay for Angiogenic Potential:

- Objective: Quantify the pro-angiogenic effects of stem cell secretions [23].

- Methodology: Plate human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) on Matrigel or similar basement membrane matrix. Treat with MSC-conditioned media or purified factors. Incubate for 4-18 hours and visualize tube networks. Analyze by measuring total tube length, number of branches, and junction points using image analysis software [23].

- Key Measurements: Total tube length, number of branches, junction points per field.

Clinical Translation of Paracrine Mechanisms

The paracrine hypothesis has significant clinical implications, suggesting that cell-free therapies utilizing conditioned media or isolated extracellular vesicles could potentially replicate stem cell benefits while minimizing risks associated with whole-cell transplantation [24]. This approach offers practical advantages including standardized manufacturing, extended shelf life, and reduced safety concerns related to cell viability and differentiation potential [24]. In cardiovascular clinical trials, this mechanism is supported by observations where stem cell administration improved left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and reduced infarct size despite minimal long-term engraftment [21] [23]. Meta-analyses of RCTs have demonstrated significant long-term LVEF improvement (mean difference 2.63%, 95% CI 0.50% to 4.76%, p=0.02) following stem cell therapy in acute myocardial infarction patients [21].

Tissue Repair and Regeneration: Direct and Indirect Mechanisms

The capacity of stem cells to directly contribute to tissue repair encompasses both differentiation into functional somatic cells and the activation of endogenous repair programs.

Differentiation Capacity Across Stem Cell Types

Different stem cell populations exhibit varying differentiation potential. Mesenchymal stem cells demonstrate multipotent capacity, differentiating into mesodermal lineages including osteoblasts, chondrocytes, and adipocytes [10]. Embryonic stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells offer pluripotency, with the ability to generate all somatic cell types, including cardiomyocytes and neurons [10] [7]. Tissue-resident progenitor cells, such as cardiac stem cells, exhibit more restricted differentiation potential typically limited to their tissue of origin [7].

Endogenous Regeneration Activation

Beyond direct differentiation, stem cells activate endogenous repair mechanisms by stimulating resident tissue-specific progenitor cells through paracrine signaling [23] [10]. This is particularly important in tissues with limited regenerative capacity, such as neuronal and cardiac tissue. The secretion of factors like brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) by MSCs promotes neuronal survival and outgrowth, while stem cell factor (SCF) mobilizes bone marrow-derived progenitors to participate in tissue repair [23] [10].

Experimental Toolkit for Mechanism Validation

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Stem Cell Mechanism Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Isolation Kits | Ficoll-Paque for PBMC isolation, collagenase digestion kits for adipose MSCs, CD34+ selection kits [10] [24] | Isolation of specific stem cell and immune cell populations | Separation of mononuclear cells based on density; enzymatic tissue dissociation; magnetic bead-based cell selection |

| Cytokine Licensing Cocktails | Recombinant human IFN-γ, TGF-β1, TNF-α [24] | Enhancement of immunomodulatory potency | Pre-activation of MSCs to boost IDO, PGE2, PD-L1 expression; typically used at 20-50 ng/mL for 48-72 hours |

| EV Isolation Systems | Size-exclusion chromatography, ultracentrifugation, precipitation kits, tangential flow filtration [24] | Production of cell-free therapeutic fractions | Isolation of small EVs (30-150 nm) based on size, density, or surface markers |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies | CD73, CD90, CD105 (MSC markers); CD45, CD34 (negative markers); CD4, CD25, FOXP3 (Treg panel) [10] [24] | Cell phenotype characterization and functional assessment | Confirmation of stem cell identity; quantification of immune cell populations; analysis of cell surface and intracellular markers |

| Differentiation Media Kits | Osteogenic (ascorbate, β-glycerophosphate, dexamethasone), adipogenic (insulin, IBMX, dexamethasone), chondrogenic (TGF-β3, BMP-6) [10] | Validation of stem cell multipotency | Induction of lineage-specific differentiation through cytokine and chemical induction |

In Vivo Model Systems

Animal models remain essential for validating stem cell mechanisms in complex physiological environments. For cardiovascular applications, rodent and porcine myocardial infarction models (induced by permanent coronary artery ligation or ischemia-reperfusion) demonstrate functional improvements following stem cell therapy, including reduced infarct size and enhanced ventricular function [23]. In neurological research, middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) models for stroke show significant functional recovery with stem cell treatment, with meta-analyses reporting improved modified Rankin Scale scores at 90 days (RR=1.31, 95% CI=1.01-1.70) and 1 year (RR=1.74, 95% CI=1.09-2.77) [8]. For wound healing applications, diabetic murine models (e.g., db/db mice) demonstrate accelerated wound closure with adipose-derived MSC therapy through enhanced angiogenesis and tissue remodeling [26].

Comparative Efficacy in Randomized Clinical Trials

RCT evidence supporting stem cell mechanisms varies substantially across medical conditions, reflecting differences in therapeutic applications and trial methodologies.

Table 4: Stem Cell Efficacy Outcomes Across Medical Specialties Based on RCT Evidence

| Medical Condition | Primary Efficacy Outcomes | Safety Profile | Level of Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute Myocardial Infarction | Long-term LVEF improvement (2.63%, p=0.02); reduced relative infarct size; no short-term benefit [21] | Fewer adverse events vs controls (OR 0.66, 95% CI 0.44-0.99); no cardiac-related cancers [21] | Meta-analysis of 15 trials (n=1,218) [21] |

| Ischemic Stroke | Improved mRS scores 0-2 at 90 days (RR=1.31, 95% CI=1.01-1.70); mRS 0-1 at 1 year (RR=1.74, 95% CI=1.09-2.77) [8] | No significant difference in serious adverse events or mortality [8] | Meta-analysis of 13 trials (n=872) [8] |

| Chronic Wounds | Complete healing in 56% vs 38% controls (p=0.0042); reduced healing time (65 vs 90 days) [26] | Similar adverse events with fewer osteomyelitis cases and amputations [26] | Multicenter RCT (n=208) with bioengineered skin substitutes [26] |

| Advanced Heart Failure | Varied efficacy across cell types; consistent safety demonstration [7] | Clinically acceptable safety across multiple cell types [7] | Systematic review of 27 clinical trials [7] |

The therapeutic efficacy of stem cells in randomized clinical trials results from the integrated operation of immune modulation, paracrine signaling, and tissue repair mechanisms rather than any single pathway. The relative contribution of each mechanism varies depending on stem cell type, tissue environment, and disease pathology. Current evidence suggests that paracrine signaling and immune modulation may deliver more immediate therapeutic effects, while direct differentiation likely contributes to longer-term tissue restoration. Future research directions should prioritize standardized protocols for cell manufacturing and delivery, development of potency assays based on mechanism-specific biomarkers, and exploration of combination therapies that enhance endogenous regenerative responses. The evolving understanding of extracellular vesicles as primary mediators of stem cell efficacy offers promising opportunities for cell-free therapeutic strategies that may overcome current challenges in stem cell transplantation while maintaining therapeutic benefits.

Clinical Trial Design and Therapeutic Application Across Indications

Autoimmune and liver diseases represent a significant global health burden, often progressing to chronic, debilitating conditions with limited treatment options. Within the evolving landscape of regenerative medicine, stem cell therapy has emerged as a promising intervention aimed at addressing the underlying pathophysiology of these conditions rather than merely alleviating symptoms. This analysis critically examines the disease-specific efficacy of stem cell therapies, with a particular focus on outcomes from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in both autoimmune and hepatic disorders. The evaluation is structured around core therapeutic mechanisms, including immunomodulation, tissue regeneration, and anti-fibrotic effects, which are quantified through clinical, biochemical, and histological endpoints. By synthesizing current evidence from active clinical trials and published meta-analyses, this guide provides a comparative framework for researchers and drug development professionals to understand the positioning of stem cell therapies within the current therapeutic arsenal and to inform future clinical development strategies.

Comparative Efficacy of Stem Cell Therapies in Autoimmune Diseases

Stem cell therapy has shown variable efficacy across different autoimmune diseases, with the most robust evidence emerging from RCTs in Crohn's disease (CD), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and scleroderma. The therapeutic effect is primarily mediated through immune modulation and tissue repair mechanisms, with outcomes highly dependent on cell source, administration route, and patient selection.

Table 1: RCT Outcomes for Stem Cell Therapies in Autoimmune Diseases

| Disease | Stem Cell Type | Primary Endpoint(s) | Key Efficacy Findings | Reported Clinical Remission Rate | Major Adverse Events |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crohn's Disease (CD) [12] | Hematopoietic Stem Cells (HSCs), Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | Clinical remission, endoscopic improvement | Sustained drug-free remission, fistula healing | Middle to High (>50% - >75%) [12] | Infections, cytopenias (HSC-based therapy) |

| Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) [27] [12] | MSCs, CAR T-cells | Disease activity index (e.g., BILAG), serological markers | Durable drug-free remission, normalized complement, reduced anti-dsDNA titers [27] | Middle to High (>50% - >75%) [12] | Mild cytokine release syndrome (CAR-T) [27] |

| Scleroderma [12] | HSCs, MSCs | Skin score (mRSS), overall survival | Improved skin flexibility, stabilization of organ function | Middle (>50% - ≤75%) [12] | Treatment-related mortality (HSC-based therapy) |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) [12] | MSCs | ACR20/50/70 response, DAS28 score | Reduction in joint swelling, tenderness, and pain | Low to Middle (≤50% - ≤75%) [12] | Infusion-related reactions |

| Multiple Sclerosis (MS) [27] | HSCs, CAR T-cells (preclinical) | EDSS score, relapse rate | Long-term remission, reduced disability progression [27] | Information missing | Information missing |

The table illustrates that CD and SLE are the most responsive to stem cell therapy, often achieving high remission rates. A global analysis of clinical trials indicates that over 80% of stem cell trials for autoimmune diseases are in early phases (I-II), with the U.S. and China leading in trial volume [12]. The efficacy is driven by several core mechanisms. MSCs secrete soluble factors like TGF-β, PGE2, and IDO, and exosomes containing regulatory miRNAs (e.g., miR-21, miR-146a) to suppress pathogenic Th1 and Th17 cells while promoting regulatory T cell (Treg) expansion [12]. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) utilizes high-dose immunosuppression to ablate the aberrant immune system and rebuild a tolerant one from the reinfused HSCs, demonstrating long-term remission potential in scleroderma and MS [12]. Emerging therapies like CD19-directed CAR T-cells achieve a profound "reset" of immune tolerance by selectively eliminating autoreactive B cells, leading to drug-free remission in refractory SLE [27].

Comparative Efficacy of Stem Cell Therapies in Liver Diseases

For liver diseases, stem cell therapy demonstrates significant promise in improving liver function and reversing fibrosis, particularly in acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) and cirrhosis. The efficacy is measured through scoring systems, biochemical markers, and histological improvement.

Table 2: RCT Outcomes for Mesenchymal Stem Cell (MSC) Therapies in Liver Diseases

| Disease | Cell Source & Route | Primary Endpoint | Key Efficacy Findings | Significance (p-value) | Major Adverse Events |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure (ACLF) [28] | UC-MSCs, BM-MSCs; Intravenous/ Hepatic Artery | MELD score, Albumin (ALB) | Decreased MELD score, increased ALB at 4 & 24 weeks | p < 0.05 [28] | No significant increase in AEs/SAEs [28] |

| Liver Cirrhosis [29] [30] | BM-MSCs, UC-MSCs; Intravenous | Histological fibrosis, liver function tests | Reduced liver scarring, improved synthetic function | p < 0.05 in multiple trials [29] | Mild, transient post-infusion reactions |

| Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD) [31] | Information missing | Liver fat content, fibrosis stage | Potential to reduce inflammation and scarring | Information missing | Information missing |

Meta-analyses of RCTs confirm that MSC infusion is effective and safe for ACLF patients, improving liver function without increasing adverse events [28]. The therapeutic potential of MSCs in liver diseases is primarily mediated through three interconnected mechanisms. MSCs create an immunosuppressive environment by secreting factors like PGE2, IDO, and HLA-G, which modulate T cells, B cells, NK cells, dendritic cells (DCs), and macrophages (MΦs), shifting them from a pro-inflammatory to an anti-inflammatory phenotype [30]. They also attenuate liver fibrosis by secreting HGF and other factors that inhibit the activation of hepatic stellate cells (HSCs)—the main collagen-producing cells—and promote the degradation of excess extracellular matrix [29] [30]. Furthermore, MSCs promote tissue repair by releasing growth factors like HGF and VEGF, which support the regeneration of endogenous hepatocytes, and can potentially differentiate into hepatocyte-like cells [29] [30]. Extracellular vesicles from MSCs (MSC-EVs) have emerged as a cell-free alternative, delivering bioactive cargo like microRNAs that regulate immune function and inhibit cell death [29].

Key Experimental Protocols in Stem Cell Clinical Trials

MSC Therapy for Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure (ACLF)

The efficacy of MSCs in ACLF is established through rigorous RCT protocols. A recent meta-analysis followed the PRISMA statement and Cochrane guidance, sourcing data from PubMed, Web of Science, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library [28]. The study selection adhered to the PICOS principle: Population: patients diagnosed with ACLF; Intervention: MSC infusion; Comparison: conventional medical therapy; Outcomes: MELD score, Albumin (ALB), international normalized ratio (INR), alanine aminotransferase (ALT); Study design: RCTs [28]. The quality of included studies was assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias tool. Statistically, continuous outcomes were analyzed using the standardized mean difference (SMD) with a 95% confidence interval (CI), while dichotomous data used the odds ratio (OR) with 95% CI. Heterogeneity was quantified with the I² statistic, applying a fixed-effects model if I² < 50% and p > 0.1, and a random-effects model otherwise [28]. This rigorous methodology confirmed that MSC treatment significantly improved MELD scores and ALB levels at both 4 and 24 weeks compared to the control group [28].

CAR T-Cell Therapy for Autoimmune Diseases

The protocol for adapting CAR T-cell therapy for autoimmune diseases like SLE involves a multi-step process. First, leukapheresis is performed to collect a patient's T cells [27]. These T cells are then genetically engineered ex vivo to express synthetic chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) targeting specific immune cell markers, such as CD19 on B cells or BCMA on plasma cells [27]. The engineered CAR T-cells are expanded in culture to achieve a sufficient therapeutic dose. Before infusion, patients often receive lymphodepleting chemotherapy (e.g., with cyclophosphamide and fludarabine) to enhance the engraftment and persistence of the CAR T-cells [27]. Finally, the CAR T-cells are infused back into the patient, where they initiate the targeted elimination of autoreactive B-lineage cells, leading to a "resetting" of immune tolerance. This approach has resulted in durable drug-free remission in patients with refractory SLE [27].

Visualization of Key Mechanisms and Workflows

Stem Cell Mechanisms in Liver Fibrosis

Diagram Title: MSC Mechanisms Against Liver Fibrosis

CAR T-Cell Workflow for Autoimmunity

Diagram Title: CAR T-Cell Therapy Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Stem Cell Therapy Research

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function in R&D | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) [28] [30] [12] | Core therapeutic agent; source of immunomodulation and trophic factors. | Investigated in >50 clinical trials for liver cirrhosis; most common cell type in autoimmune trials [29] [12]. |

| Hematopoietic Stem Cells (HSCs) [12] | Core therapeutic agent for immune system reconstitution. | Used in high-dose immunosuppression/chemotherapy protocols for scleroderma and MS [12]. |

| CAR Transduction Vectors [27] | Genetic engineering of autologous T cells. | Creating CD19- or BCMA-targeting CAR T-cells for SLE and other autoimmune diseases [27]. |

| Cell Culture Media & Supplements | Ex vivo expansion and maintenance of stem cells. | Critical for growing MSCs and expanding CAR T-cells to sufficient doses for therapy [27]. |

| Hepatocyte Growth Factor (HGF) [29] [30] | Key paracrine factor; promotes liver regeneration and inhibits HSC activation. | A major mediator of the anti-fibrotic and regenerative effects observed in MSC-based liver therapies [29] [30]. |

| Extracellular Vesicles (EVs)/Exosomes [29] [12] | Cell-free therapeutic alternative; carry regulatory miRNAs and proteins. | MSC-EVs are being explored to treat liver failure and mitigate complications, mimicking MSC effects [29]. |

The therapeutic potential of stem cell therapy in regenerative medicine and for treating immune-mediated inflammatory diseases is immense, yet its clinical translation faces significant challenges [10]. The efficacy of these therapies in randomized clinical trials is not solely dependent on the type of stem cell selected but is profoundly influenced by three critical trial parameters: cell dosage, delivery routes, and timing windows. These parameters are interdependent pillars that determine the cellular fate, biodistribution, and ultimate therapeutic success [32] [33]. A comprehensive analysis of global clinical trials reveals that most (83.6%) are in early to mid-phase (Phase I-II), underscoring the ongoing efforts to optimize these fundamental aspects [34]. The absence of universal guidelines for administration, as noted in cardiac regeneration trials, exemplifies the broader challenge across therapeutic areas [32]. This guide objectively compares current strategies and supporting experimental data for these parameters, providing a framework for researchers and drug development professionals to enhance clinical trial design within the broader thesis of optimizing stem cell therapy efficacy.

Cell Dosage: Balancing Efficacy and Safety

Cell dosage is a primary determinant of therapeutic outcome, influencing both the potency of the intervention and its safety profile. Dosing strategies must account for the specific disease pathology, stem cell source, and desired mechanism of action—whether for immune modulation, tissue repair, or a combination thereof.

Dosage Ranges and Disease-Specific Considerations

The optimal cell dose varies significantly across disease areas and cell types. In advanced heart failure trials, mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) doses have ranged from 20 to 150 million cells per infusion, with higher doses often associated with more pronounced improvements in cardiac function, though not consistently across all studies [7]. For autoimmune conditions like Crohn's disease and systemic lupus erythematosus, clinical trials have employed a wide spectrum of doses, reflecting the ongoing search for an optimal range [34]. The therapeutic effect in many contexts is mediated primarily through paracrine signaling—the release of bioactive molecules such as growth factors, cytokines, and extracellular vesicles—rather than direct cell engraftment [10] [7]. This mechanism suggests that a minimum threshold dose is necessary to achieve a critical concentration of these therapeutic factors at the target site.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Stem Cell Dosing in Clinical Trials

| Therapeutic Area | Cell Type | Common Dosing Range | Key Efficacy Findings | Safety Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advanced Heart Failure [7] | Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | 20 - 150 million cells | Promising outcomes; efficacy varies and is not yet conclusively confirmed. | Clinically acceptable safety profile across trials. |

| Autoimmune Diseases (e.g., Crohn's, SLE) [34] | MSCs, Hematopoietic Stem Cells (HSCs) | Wide spectrum reported | Disease-specific variations in clinical remission rates. | Lack of robust long-term safety data; mild immune rejection possible with allogeneic MSCs. |

| Graft-versus-Host Disease (GVHD) Prophylaxis [35] | MSCs | Context-dependent | Prophylactic administration reduces incidence. | Risks must be balanced against efficacy. |

Experimental Protocols for Dose Optimization