Stem Cell Transplantation for Myocardial Infarction: Techniques, Efficacy, and Future Directions in Regenerative Cardiology

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of stem cell transplantation techniques for myocardial infarction (MI), tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Stem Cell Transplantation for Myocardial Infarction: Techniques, Efficacy, and Future Directions in Regenerative Cardiology

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of stem cell transplantation techniques for myocardial infarction (MI), tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational science behind cardiac regeneration, details various methodological approaches and cell types—including mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), and cardiac stem cells (CSCs). The content examines the primary challenges in the field, such as low cell survival and retention, and synthesizes the latest optimization strategies from recent preclinical and clinical studies. Furthermore, it presents a critical evaluation of clinical efficacy and safety data, including long-term outcomes from meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. By integrating current evidence with emerging technologies, this review serves as a strategic resource for guiding future research and clinical translation in cardiovascular regenerative medicine.

The Science of Cardiac Repair: Stem Cell Types and Regenerative Mechanisms

Pathophysiology of Myocardial Infarction and the Need for Regeneration

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) remains a leading cause of global mortality, responsible for approximately 18.6 million deaths annually worldwide [1]. Despite advances in reperfusion therapies and pharmacological interventions, contemporary treatments fail to regenerate lost cardiomyocytes, leaving behind noncontractile scar tissue that predisposes patients to heart failure [1] [2]. The adult human heart has limited regenerative capacity, with cardiomyocyte turnover rates declining from 1% at age 25 to 0.45% by age 75 [3]. This fundamental limitation has spurred significant research into stem cell transplantation techniques to replenish lost myocardium and restore cardiac function. This application note examines the molecular pathogenesis of AMI and details experimental protocols for stem cell-based regenerative approaches, providing researchers with methodologies to investigate cardiac repair mechanisms.

Pathophysiological Mechanisms of Myocardial Infarction

Molecular Pathways in Acute Myocardial Infarction

The pathophysiology of AMI involves a complex cascade of molecular events beginning with coronary artery occlusion and culminating in irreversible cardiomyocyte death. Key mechanisms include oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, inflammatory activation, and programmed cell death pathways [4].

Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction: During ischemia, interrupted oxygen supply disrupts the mitochondrial electron transport chain, generating excessive superoxide anions and reactive oxygen species (ROS) [4]. The sudden reintroduction of oxygen during reperfusion triggers a dramatic ROS burst through reverse electron transport at mitochondrial complex I, establishing a vicious cycle of oxidative damage [4]. Concurrent calcium overload promotes sustained opening of mitochondrial permeability transition pores (mPTP), exacerbating mitochondrial impairment and cardiomyocyte death [4].

Inflammatory Cascade: Necrotic cardiomyocytes release damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), including HMGB1, HSP, and S100A8/A9, which activate pattern recognition receptors (TLRs, NLRP3 inflammasome, RAGE) [4]. This interaction triggers pro-inflammatory cytokine release (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α) and recruits Ly6Chi monocytes and neutrophils to the infarct zone, initiating a robust inflammatory response [4].

Programmed Cell Death: Multiple cell death pathways, including apoptosis, necroptosis, and pyroptosis, are activated during AMI, collectively contributing to the substantial loss of cardiomyocytes [4]. These pathways are modulated by epigenetic regulators that influence gene expression throughout the infarction and repair process.

Table 1: Key Molecular Mediators in AMI Pathogenesis

| Molecular Category | Key Mediators | Biological Function | Experimental Detection Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidative Stress Markers | ROS, NOX, NOS, SOD, CAT, GPX | Redox balance regulation | Fluorescent probes (DCFDA), ELISA, Western blot |

| Inflammatory DAMPs | HMGB1, HSP, S100A8/A9 | Immune cell activation | ELISA, immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry |

| Cell Death Executors | Caspases, RIPK1/RIPK3, MLKL | Programmed cell death | TUNEL assay, caspase activity assays, Western blot |

| Mitochondrial Components | mPTP, ETC complexes, mtDNA | Energy production, apoptosis regulation | Seahorse analyzer, JC-1 staining, mitochondrial isolation |

Ventricular Remodeling Post-Infarction

Following AMI, the heart undergoes structural and functional changes known as ventricular remodeling, characterized by infarct expansion, hypertrophy of non-infarcted myocardium, and progressive chamber dilation [4]. This process is driven by persistent neurohormonal activation, sustained inflammation, and fibrotic replacement of contractile tissue, ultimately leading to decreased cardiac output and heart failure development. Epidemiological data indicate that approximately 20% of AMI patients develop heart failure within 5 years after the initial event [1].

Stem Cell-Based Regenerative Approaches

Stem Cell Types and Mechanisms of Action

Several stem cell populations have been investigated for cardiac regeneration, each with distinct advantages and limitations for myocardial repair.

Table 2: Stem Cell Types for Myocardial Regeneration

| Stem Cell Type | Sources | Key Advantages | Major Limitations | Primary Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | Bone marrow, adipose tissue, umbilical cord | Strong immunomodulation, abundant paracrine function, low immunogenicity | Low survival post-transplantation (<10%), functional heterogeneity | Paracrine signaling, immune regulation, homing effects |

| Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) | Reprogrammed somatic cells | ESC differentiation potential, autologous transplantation, high cardiomyocyte purity (95%) | Tumorigenic risk, residual epigenetic memory, ectopic differentiation | Direct differentiation into cardiomyocytes |

| Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) | Inner cell mass of blastocyst | High differentiation efficiency (70-85%), secrete angiogenic factors | Ethical concerns, tumorigenic risk, immune rejection | Direct differentiation |

| Cardiac Stem Cells (CSCs) | Adult heart | Direct transplantation to damaged heart, tissue-specific | Limited studies, mechanisms not fully elucidated | Exosome secretion, angiogenesis, anti-apoptosis |

Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs): MSCs primarily exert therapeutic effects through paracrine signaling rather than direct differentiation [1]. They secrete exosomes containing microRNAs (miR-21, miR-210) that regulate cardiomyocyte apoptosis and fibrosis, along with growth factors (VEGF, HGF, FGF) that promote angiogenesis [1]. MSC recruitment of endogenous progenitor cells occurs via the CCL2/CCR2 axis, enhancing tissue repair [1].

Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs): iPSCs are generated by reprogramming somatic cells with transcription factors (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc) and can differentiate into functional cardiomyocytes with approximately 95% purity using directed differentiation protocols [1]. The first iPSC-derived myocardial cell sheet transplantation trial in Japan (jRCT2052190081) demonstrated significant improvement in myocardial perfusion in 4 of 5 heart failure patients [1].

Extracellular Vesicles (EVs): Stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles (Stem-EVs) have emerged as promising cell-free alternatives for cardiac regeneration [3]. These nano-sized vesicles carry therapeutic cargo (miRNAs, mRNAs, proteins) and demonstrate anti-inflammatory, antiapoptotic, and angiogenic benefits when administered in animal models of AMI, resulting in reduced infarct size and improved cardiac function [3].

Key Signaling Pathways in Cardiac Repair

Stem cell therapies activate multiple signaling pathways to promote cardiac repair:

- Paracrine Signaling: MSC-secreted factors (VEGF, FGF, HGF) activate PI3K/Akt and MAPK pathways, promoting angiogenesis and cell survival [1].

- Immune Modulation: MSCs shift macrophage polarization from pro-inflammatory M1 to anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype via TSG-6 and PGE2 secretion [1].

- Direct Differentiation: iPSCs and ESCs differentiate into cardiomyocytes through sequential activation of Wnt, BMP, and Notch signaling pathways [1] [3].

- In Vivo Reprogramming: Cardiac fibroblasts can be directly reprogrammed to induced cardiomyocyte-like cells (iCMs) via forced expression of GMT (GATA4, Mef2C, Tbx5) or GHMT (GATA4, Hand2, Mef2C, Tbx5) transcription factors [3].

Experimental Protocols for Myocardial Regeneration Research

Protocol: MSC Transplantation in Murine Myocardial Infarction Model

Objective: To evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of mesenchymal stem cells in a murine model of myocardial infarction.

Materials and Equipment:

- 8-12 week old C57BL/6 mice

- Human bone marrow-derived MSCs (commercially available)

- LAD ligation surgical instruments

- Isoflurane anesthesia system

- Echocardiography system (Vevo 2100)

- Flow cytometry reagents for immune profiling

- Histology supplies (formalin, paraffin, sectioning equipment)

Procedure:

Myocardial Infarction Induction:

- Anesthetize mice with 2% isoflurane and maintain with 1.5% during surgery.

- Perform endotracheal intubation and connect to mechanical ventilation.

- Make left thoracotomy between 3rd and 4th ribs to expose the heart.

- Identify the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery and permanently ligate with 7-0 silk suture.

- Confirm successful infarction by visual observation of myocardial blanching.

Stem Cell Preparation and Transplantation:

- Culture MSCs in complete DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS until 80% confluent.

- Label cells with GFP or DIR dye for tracking (optional).

- Harvest cells using trypsin/EDTA and resuspend in PBS at 1×10^6 cells/50µL.

- Immediately following LAD ligation, intramyocardially inject cell suspension at 3-4 sites around the infarct border zone.

- For control group, inject equivalent volume of PBS only.

Functional Assessment:

- Perform transthoracic echocardiography at days 0, 7, 14, and 28 post-MI.

- Measure left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), left ventricular end-systolic volume (LVESV), and left ventricular end-diastolic volume (LVEDV).

- Conduct hemodynamic measurements using pressure-volume loops at endpoint.

Histological Analysis:

- Euthanize animals at study endpoint and perfuse with PBS followed by 4% PFA.

- Excise hearts, post-fix in 4% PFA for 24h, then embed in paraffin.

- Section hearts at 5µm thickness for staining.

- Perform Masson's trichrome staining to quantify fibrotic area.

- Immunostain for CD31 to assess capillary density.

- Use TUNEL assay to quantify apoptotic cells.

Molecular Analysis:

- Extract RNA from infarct border zone tissue using TRIzol method.

- Perform RT-qPCR for angiogenesis markers (VEGF, Ang1), inflammation markers (IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-10), and fibrotic markers (TGF-β, collagen I/III).

- Analyze macrophage polarization via flow cytometry using CD86 (M1) and CD206 (M2) markers.

Expected Outcomes: MSC-treated animals should demonstrate significantly improved LVEF (approximately 3.8% increase), reduced infarct size, enhanced capillary density, and modulated inflammatory response compared to PBS controls [1] [2].

Protocol: iPSC-Derived Cardiomyocyte Differentiation and Transplantation

Objective: To generate functional cardiomyocytes from induced pluripotent stem cells and assess their therapeutic potential in myocardial infarction models.

Materials:

- Human iPSCs (commercially available or patient-derived)

- Cardiomyocyte differentiation kit (or individual components)

- RPMI 1640 medium, B-27 supplements

- Growth factors: Activin A, BMP4, CHIR99021, IWP2

- Immunocytochemistry antibodies: cardiac troponin T, α-actinin, MLC2v

- Multi-electrode array system for electrophysiological assessment

Procedure:

Cardiomyocyte Differentiation:

- Culture iPSCs in mTeSR1 medium on Matrigel-coated plates until 80-90% confluent.

- Initiate differentiation by switching to RPMI/B-27 minus insulin medium containing 6µM CHIR99021 (GSK3β inhibitor).

- After 24h, replace medium with RPMI/B-27 minus insulin alone.

- At day 3, add RPMI/B-27 minus insulin containing 5µM IWP2 (Wnt inhibitor).

- On day 5, replace with RPMI/B-27 minus insulin.

- On day 7, switch to RPMI/B-27 complete medium and maintain with medium changes every 2-3 days.

- Spontaneous contracting cells should appear between days 8-12.

Cardiomyocyte Purification:

- At day 12-15, replace medium with glucose-free RPMI supplemented with 4mM lactate for metabolic selection.

- Maintain lactate medium for 4-6 days to eliminate non-cardiomyocytes.

- Return to normal RPMI/B-27 complete medium.

Characterization:

- Fix cells and immunostain for cardiac markers: cardiac troponin T, α-actinin, MLC2v.

- Analyze sarcomeric organization via confocal microscopy.

- Assess electrophysiological properties using multi-electrode array.

- Perform flow cytometry to quantify cardiomyocyte purity.

Transplantation:

- Dissociate cardiomyocytes using collagenase-based cell dissociation reagent.

- Resuspend in PBS at 1×10^7 cells/100µL for transplantation.

- Transplant into immunodeficient mice or immunosuppressed large animal models of myocardial infarction using intramyocardial injection.

- Monitor for arrhythmias via continuous ECG monitoring post-transplantation.

Expected Outcomes: Successful differentiation should yield >90% pure cardiomyocytes with typical sarcomeric organization and spontaneous contraction [1]. Transplantation studies should demonstrate improved myocardial function and electrical integration, though arrhythmogenic risk remains a concern [3].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Cardiac Regeneration Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Products | Research Application | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stem Cell Culture | MesenCult MSC Medium, mTeSR Plus, Matrigel | MSC and iPSC maintenance | Provides optimal growth conditions for stem cell expansion |

| Differentiation Kits | STEMdiff Cardiomyocyte Kit, Gibco PSC Cardiomyocyte Kit | Cardiac differentiation from pluripotent stem cells | Directed differentiation into functional cardiomyocytes |

| Cell Tracking | DIR dye, GFP/Lentivirus, CM-Dil | Cell fate mapping | Enables tracking of transplanted cells in vivo |

| Functional Assessment | Vevo 2100 Imaging System, Pressure-Volume Catheter | Cardiac function analysis | Measures hemodynamic parameters and ejection fraction |

| Molecular Analysis | TaqMan assays for cardiac markers, RNA-seq kits | Gene expression profiling | Quantifies molecular changes in response to therapy |

| Histology | Cardiac troponin T antibodies, Masson's trichrome kit | Tissue characterization | Identifies cardiomyocytes and quantifies fibrosis |

Challenges and Future Perspectives

Despite promising preclinical results, stem cell therapy for myocardial infarction faces significant translational challenges. The low survival rate of transplanted stem cells (less than 5% within 72 hours for MSCs) remains a major bottleneck [1]. Additionally, uncontrolled differentiation, potential tumorigenicity (particularly with iPSCs and ESCs), and arrhythmogenic risk present substantial hurdles [1] [3].

Future directions include the development of combinatorial approaches using biomaterial scaffolds to enhance cell retention and survival. Smart hydrogel scaffolds and 3D bioprinting technology show promise for creating functional cardiac tissue constructs [1]. Engineered extracellular vesicles with enhanced cardiac targeting and recombinant therapeutic cargo represent another emerging strategy [3]. Gene editing technologies like CRISPR-Cas9 offer opportunities to precisely regulate stem cell lineage commitment and improve therapeutic efficacy [1].

As research progresses, multidisciplinary approaches integrating stem cell biology, biomaterials engineering, and gene editing are expected to drive the development of precise, intelligent, and systematic stem cell therapies for myocardial infarction and atherosclerosis [1].

The pursuit of effective stem cell-based therapies for myocardial infarction (MI) represents a cornerstone of modern cardiovascular regenerative medicine. The irreversible loss of cardiomyocytes following ischemic injury is a primary driver of heart failure, a condition with a post-diagnosis 5-year survival rate of merely 50% [3]. Conventional pharmacological and device-based treatments manage symptoms but fail to address the fundamental loss of contractile heart tissue [3]. Stem cell transplantation has emerged as a promising strategy to repopulate damaged myocardium, improve cardiac function, and alter the progression towards heart failure. Among the diverse cell types investigated, Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs), Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs), Cardiac Stem Cells (CSCs), and Skeletal Myoblasts have been identified as major candidates, each with distinct advantages and challenges. This application note details the experimental protocols, functional outcomes, and key reagents for utilizing these cells in MI research, providing a framework for preclinical investigation.

Comparative Analysis of Stem Cell Candidates

The following tables summarize the key characteristics, therapeutic mechanisms, and functional outcomes of the four major stem cell candidates in MI research.

Table 1: Characteristics and Therapeutic Mechanisms of Stem Cell Candidates

| Stem Cell Type | Source | Key Markers | Major Proposed Mechanisms of Action in MI |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSCs | Bone Marrow, Adipose Tissue, Umbilical Cord | CD73+, CD90+, CD105+; CD45-, CD34- [5] | - Paracrine secretion of anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic, and pro-angiogenic factors [6] [3].- Stimulation and proliferation of endogenous CSCs [7].- Immunomodulation [8]. |

| iPSCs | Reprogrammed Somatic Cells (e.g., Fibroblasts) | Oct3/4, Sox2, c-Myc, Klf4 (during reprogramming) [9] | - In vitro differentiation into cardiomyocytes (iPSC-CMs) for transplantation [10] [9].- Source for deriving induced MSCs (iMSCs) with enhanced proliferative capacity [5]. |

| CSCs | Cardiac Tissue (e.g., atrial appendages) | c-kit+, GATA-4+ [7] | - Direct differentiation into cardiomyocytes and vascular endothelial cells [11].- Activation of endogenous repair pathways (e.g., Wnt/β-catenin, Notch) [11]. |

| Skeletal Myoblasts | Skeletal Muscle | Desmin+ [12] | - Differentiation into myotubes that provide contractile force [12].- High resistance to ischemia. |

Table 2: Summary of Efficacy and Safety Outcomes from Preclinical and Clinical Studies

| Stem Cell Type | Reported Efficacy Outcomes | Reported Safety Risks | Clinical Trial Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSCs | - ↑ LVEF; ↓ infarct size (e.g., from 24.9% to 10.9% LV mass in swine) [7].- Improved remodeling, angiogenesis [6]. | - Low long-term cell retention [6] [3].- Variable outcomes in clinical trials [8]. | Multiple clinical trials completed (e.g., TAC-HFT, POSEIDON) showing safety and variable functional improvement [13] [3]. |

| iPSC-CMs | - ↑ LVEF (MD +8.23%) and ↑ Fractional Shortening (MD +5.16%) in meta-analysis [9].- Reduced fibrosis (MD -7.62%) [9]. | - Risk of teratoma from undifferentiated cells [9].- Arrhythmogenesis post-transplantation [9] [3]. | Preclinical stage; no human trials identified in meta-analysis [9]. |

| CSCs | - 20-fold increase in endogenous c-kit+ CSCs after MSC-mediated stimulation [7].- Promoted cardiomyocyte regeneration in models [11]. | - Limited cell number in adult heart, making isolation difficult [11]. | Early-stage clinical trials; outcomes have been mixed [3]. |

| Skeletal Myoblasts | - Improved regional contractility in infarcted area [12]. | - High incidence of ventricular arrhythmia [12]. | Clinical trials (e.g., MAGIC) showed arrhythmic risk, limiting application [12]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Investigations

Protocol: Assessing MSC-Mediated Endogenous CSC StimulationIn Vivo

This protocol is based on a porcine model of MI designed to investigate the paracrine-mediated effects of MSCs on host cardiac stem cells [7].

Workflow: MSC Mediated Endogenous CSC Stimulation

Materials:

- Animals: Female Yorkshire swine (25-35 kg) [7].

- MSCs: Allogeneic male porcine bone marrow-derived MSCs, transduced with GFP for tracking [7].

- Control Injectates: Placebo (e.g., Plasmalyte) or concentrated conditioned medium (CCM) [7].

Methodology:

- Myocardial Infarction (MI) Induction: Subject animals to experimental MI followed by reperfusion [7].

- Cell Preparation and Delivery:

- Functional and Tissue Analysis:

- Cardiac MRI: Conduct serial cMRI at baseline, post-MI, and at 2 and 8 weeks post-injection to assess ejection fraction, infarct size, and ventricular volumes [7].

- Tissue Harvesting: Sacrifice animals at predetermined time points (e.g., 2 weeks, 8 weeks). Collect tissue samples from the infarct core, border zone, and remote healthy myocardium [7].

- Histological Analysis:

- Perform immunofluorescence staining for specific markers.

- Quantify c-kit+ CSCs and GATA-4+ CSCs in the border zones.

- Identify mitotic myocytes to assess endogenous cardiomyocyte proliferation [7].

- Use Y-chromosome (e.g., FISH) or GFP staining to track the fate of injected male or GFP-labeled MSCs [7].

Protocol:In VivoTransplantation and Assessment of iPSC-Derived Cardiomyocytes

This protocol outlines the key steps for evaluating the safety and efficacy of iPSC-CMs in small and large animal models of ischemic heart disease, as synthesized from a recent meta-analysis [9].

Workflow: iPSC-CM Transplantation and Assessment

Materials:

- iPSC-CMs: Human iPSC-CMs differentiated and purified using established protocols (e.g., metabolic selection) [10] [9]. Purity must be confirmed to minimize teratoma risk.

- Animal Models: Murine or porcine models of IHD, typically induced by permanent ligation of the left anterior descending (LAD) artery [9].

- Delivery System: Catheter-based system for intramyocardial injection; consider using bioengineered tissue patches for some studies [9].

Methodology:

- Cell Preparation: Culture and prepare a single-cell suspension of iPSC-CMs. Doses in animal studies have ranged from 2 × 10^5 to 4 × 10^8 cells [9].

- IHD Model and Transplantation:

- Induce MI in the animal model.

- At the time of injection (acute or sub-acute phase), perform intramyocardial injections of iPSC-CMs directly into the infarct and border zones. Control groups should receive a vehicle solution [9].

- Outcome Assessment:

- Efficacy: Measure Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction (LVEF) and Fractional Shortening (FS) via echocardiography or cMRI at baseline and periodically during the follow-up (1-12 weeks). Quantify fibrosis percentage in histological sections at endpoint [9].

- Safety: Monitor and record all-cause mortality throughout the study. Perform continuous electrocardiography (ECG) monitoring to detect and quantify episodes of arrhythmia, particularly sustained ventricular tachycardia [9].

- Histology: Examine heart sections for graft survival, integration with host tissue (e.g., presence of gap junctions), and evidence of tumor formation.

Protocol: Direct Reprogramming of Fibroblasts to Cardiomyocytes (In Vivo)

This protocol describes a cell-free alternative for cardiac regeneration by directly reprogramming endogenous cardiac fibroblasts into induced cardiomyocyte-like cells (iCMs) in vivo [3].

Materials:

- Reprogramming Factors: Genes for cardiac transcription factors, typically GMT (GATA4, Mef2C, Tbx5) or GHMT (plus Hand2) [3].

- Delivery Vector: A non-integrating viral vector (e.g., sendai virus, adenovirus) or non-viral nanoparticles for in vivo delivery, ideally with a fibroblast-specific promoter (e.g., FSP1) to target cell specificity [3].

Methodology:

- Vector Construction: Clone the reprogramming factor cocktail (e.g., GHMT) into the chosen delivery vector.

- MI Model and Injection: Induce MI in the animal model. Immediately or shortly after, administer the viral vector/nanoparticles directly into the myocardial wall surrounding the infarct zone.

- Validation and Analysis:

- Lineage Tracing: Use transgenic mice (e.g., Postn or Tcf21 reporter lines) to label fibroblasts and confirm their conversion into iCMs.

- Functional Assessment: Evaluate cardiac function by cMRI/echocardiography. Assess electrophysiological stability by ECG.

- Molecular Phenotyping: Analyze iCMs for the expression of mature cardiac markers (e.g., α-MHC, cTnI) and the downregulation of fibroblast markers (e.g., Vimentin). Evaluate sarcomere structure via immunofluorescence.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Stem Cell-Based Myocardial Repair

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Surface Markers | CD73, CD90, CD105 (MSCs); c-kit (CSCs); SSEA-4 (iPSCs) [5] [7] | Identification, isolation, and purity assessment of specific stem cell populations via flow cytometry or immunostaining. |

| Reprogramming Factors | Oct3/4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc (iPSCs); GMT/GHMT (iCMs) [9] [3] | Induction of pluripotency in somatic cells or direct transdifferentiation of fibroblasts into cardiomyocytes. |

| Culture & Differentiation Supplements | bFGF, BMP, Activin A, PDGF-AB [5] [10] | Promoting mesodermal commitment and maintenance of MSCs during in vitro culture and differentiation. |

| Critical Animal Models | Yorkshire swine MI model; Murine LAD ligation model [7] [9] | Preclinical in vivo testing of cell safety, efficacy, and mechanisms of action. |

| Cell Delivery Devices | Transendocardial injection catheters (e.g., Stiletto) [7] | Precise, fluoroscopically-guided delivery of cell therapies to the infarct and border zones. |

| Functional Assessment Tools | Cardiac MRI (cMRI); Echocardiography; Electrocardiography (ECG) [7] [9] | Longitudinal, non-invasive measurement of functional outcomes (LVEF, volumes) and safety (arrhythmia). |

| Capsorubin | Capsorubin | Natural Apocarotenoid | For Research Use | Capsorubin is a natural red pigment and potent antioxidant for plant biology and nutrition research. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

| Beta-Asarone | Beta-Asarone, CAS:5273-86-9, MF:C12H16O3, MW:208.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Key Signaling Pathways in Cardiac Stem Cell Biology

The therapeutic action of stem cells, particularly the stimulation of endogenous repair mechanisms, involves a complex interplay of multiple signaling pathways.

Signaling Pathways in Cardiac Stem Cell Biology

Pathway Notes:

- Wnt/β-catenin: This pathway is crucial for CSC proliferation and self-renewal. Its activation leads to β-catenin stabilization and translocation to the nucleus, where it initiates the transcription of proliferation-related genes [11].

- Notch Signaling: Regulates cell fate decisions. Activation of Notch signaling in CSCs promotes their commitment and differentiation into cardiomyocytes while inhibiting alternative lineage differentiation [11].

- PI3K/Akt Pathway: A key pro-survival pathway. Its activation by MSC-secreted factors inhibits apoptosis and promotes the survival and proliferation of both endogenous CSCs and cardiomyocytes in the hostile post-infarct microenvironment [11].

Stem cell therapy has emerged as a transformative paradigm for myocardial infarction (MI) treatment, aiming to repair damaged heart tissue through core mechanistic actions: paracrine signaling, direct differentiation, and immune modulation [1] [14]. Despite advancements in conventional treatments, MI remains a leading cause of death worldwide, with approximately 15 million annual cases and about 20% of patients developing heart failure within five years post-onset [14]. Contemporary interventions often fail to achieve full functional regeneration of myocardial tissue, creating an urgent need for regenerative approaches [1]. Stem cells address this need through multifaceted mechanisms that promote tissue repair, angiogenesis, and immunomodulation, working synergistically to counteract the pathological processes driving post-infarction heart failure [15]. This document delineates the specific applications, experimental protocols, and reagent solutions underpinning these core mechanisms within myocardial infarction research contexts.

Paracrine Signaling

Mechanisms and Biological Significance

The paracrine effect represents a principal mechanism whereby stem cells secrete bioactive molecules that exert therapeutic effects on neighboring cells within damaged tissues [16]. This signaling encompasses the secretion of growth factors, cytokines, chemokines, and extracellular vesicles (including exosomes) that modulate the local cellular environment, promote angiogenesis, enhance cell survival, and exert anti-inflammatory effects [17] [18]. In the context of myocardial infarction, paracrine signaling ameliorates the ischemic microenvironment, attenuates cardiomyocyte apoptosis, and promotes functional recovery without requiring direct differentiation of the administered cells [1] [14].

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) predominantly mediate their therapeutic benefits through paracrine actions [14] [18]. Their secretome includes vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), which significantly promote angiogenesis [1]. Other critical paracrine mediators include stromal cell-derived factor-1α (SDF-1α) and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), which enhance neovascularization and reduce cardiomyocyte apoptosis in preclinical MI models [1]. Additionally, exosomes derived from MSCs carry regulatory microRNAs (e.g., miR-21, miR-210) that modulate cardiomyocyte apoptosis and fibrosis, while the CCL2/CCR2 axis facilitates the recruitment of endogenous progenitor cells to promote angiogenesis [1].

Table 1: Key Paracrine Factors in Stem Cell Therapy for Myocardial Infarction

| Paracrine Factor | Cell Source | Primary Function | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| VEGF | MSCs | Promotes angiogenesis and ameliorates ischemic microenvironment | Preclinical MI models show enhanced neovascularization [1] |

| HGF | MSCs | Promotes angiogenesis and tissue repair | Preclinical models demonstrate significant tissue repair [1] |

| SDF-1α | MSCs | Enhances neovascularization, attenuates cardiomyocyte apoptosis | Promotes functional recovery in preclinical MI models [1] |

| IGF-1 | MSCs | Attenuates cardiomyocyte apoptosis | Promotes functional recovery in preclinical MI models [1] |

| Exosomes (miR-21, miR-210) | MSCs | Regulates cardiomyocyte apoptosis and fibrosis | MSC-derived exosomes carry microRNAs that regulate apoptosis [1] |

| CCL2/CCR2 | MSCs | Recruits endogenous progenitor cells to promote angiogenesis | Clinical phase III trials confirm functional improvement [1] |

Experimental Protocol: Analyzing MSC Paracrine Secretion

Objective: To isolate and characterize the paracrine factors secreted by MSCs and evaluate their effects on cardiomyocyte survival and angiogenesis.

Materials:

- Human bone marrow-derived MSCs (commercially available)

- MSC growth medium (e.g., DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin)

- Serum-free collection medium

- Centrifugation equipment

- Ultracentrifugation equipment for exosome isolation

- Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits for VEGF, HGF, SDF-1α, IGF-1

- Angiogenesis assay kit (e.g., tube formation assay with HUVECs)

- Hypoxia chamber to simulate ischemic conditions

- Cardiomyocyte cell line (e.g., H9c2) or human pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes

Methodology:

- MSC Culture and Conditioning:

- Culture MSCs in growth medium until 80% confluent.

- Wash cells with PBS and replace with serum-free medium.

- Place cells in normoxic (21% Oâ‚‚) or hypoxic (1% Oâ‚‚) conditions for 24-48 hours to simulate ischemic environments.

- Collect conditioned medium after 24 hours for analysis.

Fractionation of Conditioned Medium:

- Centrifuge conditioned medium at 2,000 × g for 30 minutes to remove cells and debris.

- Further centrifuge at 10,000 × g for 30 minutes to remove apoptotic bodies and large vesicles.

- Isolate exosomes by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 70 minutes.

- Resolve exosome pellet in PBS for downstream applications.

Analysis of Secreted Factors:

- Quantify VEGF, HGF, SDF-1α, and IGF-1 concentrations in conditioned medium using ELISA according to manufacturer protocols.

- Characterize exosomal markers (CD9, CD63, CD81) by western blotting.

- Extract and quantify exosomal miRNAs (e.g., miR-21, miR-210) using qRT-PCR.

Functional Assays:

- Cardiomyocyte Protection Assay: Culture cardiomyocytes under hypoxic conditions with MSC-conditioned medium or isolated exosomes. Assess cell viability using MTT assay and apoptosis via TUNEL staining after 24-48 hours.

- Angiogenesis Assay: Seed HUVECs on Matrigel and treat with MSC-conditioned medium or exosomes. Quantify tube formation by measuring total tube length and branch points after 6-18 hours.

Direct Differentiation

Mechanisms and Biological Significance

Direct differentiation involves the capacity of stem cells to differentiate into functional cardiomyocytes that can directly replace lost or damaged myocardial tissue post-infarction [1]. This mechanism is particularly relevant for induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), which can be differentiated into cardiomyocytes with high purity (up to 95%) for potential transplantation therapies [1]. The world's first iPSC-derived myocardial cell sheet transplantation trial in Japan (jRCT2052190081) demonstrated significant improvement in myocardial perfusion in 4 of 5 heart failure patients [1].

Cardiac lineage commitment from pluripotent stem cells follows developmental principles, recapitulating embryonic heart development stages [19]. Key regulatory factors include ZNF711, which acts as a critical switch and safeguard for cardiomyocyte commitment, and retinoic acid (RA) signaling, which promotes atrial cardiomyocyte differentiation [19]. The differentiation process progresses through distinct stages: mesodermal progenitors (marked by EOMES), cardiac progenitors (marked by ISL1+/NKX2-5+), and finally functional cardiomyocytes expressing structural markers such as TNNT2 (cardiac troponin T) and MYL7 (myosin light chain 7) [19] [20].

Table 2: Stem Cell Types for Direct Differentiation in Cardiac Therapy

| Stem Cell Type | Source | Advantages | Limitations | Differentiation Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) | Reprogrammed somatic cells | Differentiation potential of ESCs with autologous transplantation advantages; can generate high-purity cardiomyocytes | Residual reprogramming epigenetic memory may cause differentiation bias; tumorigenic risk | Up to 95% purity with directed differentiation systems [1] |

| Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) | Inner cell mass of blastocyst | High differentiation efficiency (70-85%); secretes angiogenic factors | Ethical controversies; tumorigenic risk; immune rejection | 70-85% efficiency [1] |

| Cardiac Stem Cells (CSCs) | Adult heart | Can be transplanted directly to damaged heart; exosomes promote function recovery | Limited studies; mechanisms need further clarification | Secreted exosomes (e.g., miR-146a) promote regeneration [1] |

| Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | Bone marrow, adipose tissue, umbilical cord | Strong immunomodulation; abundant paracrine function | Low survival rate post-transplantation (<10%); functional heterogeneity | Primarily via paracrine effects rather than direct differentiation [1] |

Experimental Protocol: Directed Differentiation of iPSCs to Cardiomyocytes

Objective: To efficiently differentiate iPSCs into functional cardiomyocytes using a small molecule-based approach with high purity and reproducibility.

Materials:

- Human iPSCs (maintained in feeder-free conditions)

- Essential 8 or mTeSR1 medium for pluripotent stem cell maintenance

- RPMI 1640 medium

- B-27 supplements (with and without insulin)

- CHIR99021 (GSK-3 inhibitor)

- IWP2 or IWP4 (Wnt inhibitor)

- Matrigel or defined extracellular matrices (fibronectin, vitronectin, laminin-111)

- Accutase or EDTA solution for cell detachment

- Cardiac troponin T (cTnT) antibody for flow cytometry

- Field stimulation system for metabolic purification (optional)

Methodology:

- Maintenance of Pluripotent Stem Cells:

- Culture iPSCs on Matrigel-coated plates in Essential 8 medium.

- Passage cells every 4-5 days at 70-80% confluence using EDTA solution.

- Ensure cells maintain typical pluripotent morphology with high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio.

Cardiac Differentiation via GiWi Protocol:

- Day 0: Detach iPSCs and seed as single cells at optimal density (e.g., 1.5-2.0 × 10^5 cells/cm²) in Matrigel-coated plates with 10 μM Y-27632 ROCK inhibitor.

- Day 1: Replace medium with RPMI 1640 supplemented with B-27 without insulin. Add CHIR99021 (optimized concentration, typically 6-12 μM) to activate Wnt signaling and induce mesoderm formation.

- Day 3: Replace medium with RPMI/B-27 without insulin without CHIR99021.

- Day 5: Add IWP2 (2-5 μM) to inhibit Wnt signaling and promote cardiac mesoderm specification.

- Day 7: Replace medium with RPMI/B-27 without insulin without IWP2.

- Days 9-11: Begin metabolic selection by switching to RPMI 1640 containing glucose-free B-27 supplement and 4 mM lactate to enrich for cardiomyocytes.

Progenitor Reseeding Strategy (for Enhanced Purity):

- At day 3-4 (EOMES+ mesoderm stage) or day 5-6 (ISL1+/NKX2-5+ cardiac progenitor stage), detach cells using Accutase.

- Reseed cells at lower density (1:2.5 to 1:5 ratio by surface area) in fresh Matrigel-coated plates or defined matrices (fibronectin, vitronectin).

- Continue differentiation protocol from appropriate stage.

Characterization of Differentiated Cardiomyocytes:

- Flow Cytometry: Harvest cells at day 12-16, fix and permeabilize, then stain with anti-cTnT antibody to quantify cardiomyocyte purity.

- Functional Assessment: Record spontaneous contraction rates and analyze contractile properties using video-based analysis (e.g., MUSCLEMOTION software).

- Immunocytochemistry: Stain for cardiac-specific markers (cTnT, α-actinin, MYL2, MYL7) and assess sarcomeric organization.

- Gene Expression Analysis: Perform qRT-PCR for atrial (NR2F2, KCNA5) and ventricular (MYL2, MYH7) markers.

Immune Modulation

Mechanisms and Biological Significance

Immune modulation represents a critical mechanism whereby stem cells, particularly MSCs, suppress detrimental inflammatory responses and promote a regenerative microenvironment following myocardial infarction [1] [14] [18]. MSCs interact with various immune cells—including T cells, B cells, dendritic cells, and macrophages—through both direct cell-cell contact and secretion of immunoregulatory molecules [18]. This immunomodulatory capacity helps mitigate the excessive inflammation that contributes to adverse remodeling and heart failure progression post-MI.

MSCs modulate immune responses through multiple pathways: they suppress T cell activation and proliferation, reduce pro-inflammatory cytokine release (particularly TNF-α and IL-6), induce regulatory T cell (Treg) formation, and promote macrophage polarization toward the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype [14] [18]. The immunomodulatory functions of MSCs are activated by inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IFN-γ, TNF-α) in the microenvironment, leading to increased expression of immunomodulatory factors such as prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) [18]. This dynamic responsiveness enables MSCs to exert context-dependent immunomodulation precisely where needed.

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Immunomodulatory Properties of MSCs

Objective: To evaluate the immunomodulatory effects of MSCs on T cell responses and macrophage polarization relevant to myocardial infarction recovery.

Materials:

- Human MSCs (bone marrow or umbilical cord derived)

- Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy donors

- T cell activation reagents (anti-CD3/CD28 beads)

- Macrophage differentiation factors (M-CSF)

- Polarizing cytokines (IFN-γ, LPS for M1; IL-4 for M2)

- Flow cytometry antibodies (CD4, CD25, FoxP3, CD86, CD206)

- ELISA kits for TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10, TGF-β

- Transwell co-culture systems (for cell-cell contact experiments)

- Conditioned medium collection equipment

Methodology:

- T Cell Suppression Assay:

- Isolate PBMCs from healthy donor blood using density gradient centrifugation.

- Activate T cells using anti-CD3/CD28 beads according to manufacturer's protocol.

- Co-culture activated PBMCs with MSCs at various ratios (e.g., 1:1 to 10:1 PBMCs:MSCs) in direct contact or using transwell systems.

- After 72-96 hours, analyze T cell proliferation via CFSE dilution or BrdU incorporation.

- Assess Treg induction by flow cytometry staining for CD4, CD25, and FoxP3.

- Quantify cytokine levels (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10) in supernatant using ELISA.

Macrophage Polarization Assay:

- Differentiate monocytes from PBMCs using M-CSF (50 ng/mL) for 6 days.

- Polarize macrophages toward M1 phenotype with IFN-γ (20 ng/mL) and LPS (100 ng/mL) or toward M2 phenotype with IL-4 (20 ng/mL).

- Treat polarized macrophages with MSC-conditioned medium or co-culture with MSCs.

- After 48 hours, analyze macrophage surface markers by flow cytometry (CD86 for M1, CD206 for M2).

- Quantify secretion of phenotype-specific cytokines (TNF-α for M1; IL-10 for M2) using ELISA.

- Assess phagocytic activity using pHrodo-labeled E. coli particles.

Mechanistic Studies:

- Inhibit specific immunomodulatory pathways (IDO with 1-MT, PGE2 with indomethacin, TGF-β with neutralizing antibodies) to determine contribution to observed effects.

- Analyze MSC immunomodulatory gene expression (IDO, COX-2, TGF-β) by qRT-PCR following inflammatory priming with IFN-γ.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Stem Cell Mechanisms in Myocardial Infarction

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stem Cell Sources | Bone marrow MSCs, iPSCs, Cardiac stem cells | Provide cellular material for therapy development | Consider differentiation potential, availability, and ethical implications [1] [18] |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors/Activators | CHIR99021 (Wnt activator), IWP2/IWP4 (Wnt inhibitors), Retinoic acid | Direct stem cell differentiation toward cardiac lineages | Concentration and timing critically affect efficiency [1] [19] |

| Extracellular Matrices | Matrigel, Fibronectin, Vitronectin, Laminin-111 | Support stem cell attachment, growth, and differentiation | Defined matrices reduce batch variability [20] |

| Characterization Antibodies | Anti-cTnT, Anti-α-actinin, Anti-NKX2-5, Anti-CD90/CD105/CD73 | Identify and purify specific cell types | Validate for flow cytometry vs. immunocytochemistry [1] [18] |

| Cytokine/Chemokine Analysis | VEGF, HGF, SDF-1α, IGF-1 ELISA kits | Quantify paracrine factor secretion | Measure both constitutive and induced secretion [1] |

| Exosome Isolation Tools | Ultracentrifugation equipment, Precipitation kits, Size-exclusion chromatography | Isolate and purify extracellular vesicles | Method affects exosome yield and quality [16] |

| Thioquinapiperifil dihydrochloride | Thioquinapiperifil dihydrochloride|High-Purity RUO | Thioquinapiperifil dihydrochloride, a phosphodiesterase inhibitor for neurology research. For Research Use Only. Not for diagnostic or personal use. | Bench Chemicals |

| 3-Bromo-7-Nitroindazole | 3-Bromo-7-nitroindazole | Building Block | RUO | 3-Bromo-7-nitroindazole, a key intermediate for kinase & cancer research. High-purity, For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals |

Integrated Experimental Workflow

This application note details the core molecular pathways activated during stem cell-based therapy for myocardial infarction (MI). It provides a structured analysis of three interconnected processes—angiogenesis, anti-apoptosis, and extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling—which are critical for cardiac repair. The protocols and data presented are designed to assist researchers in quantifying these pathways to evaluate the efficacy of regenerative therapies, thereby supporting drug development and preclinical research.

Angiogenic Signaling Pathways in Cardiac Repair

Angiogenesis, the formation of new blood vessels from pre-existing vasculature, is essential for supplying oxygen and nutrients to the ischemic myocardium post-MI. Stem cells, particularly mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), promote angiogenesis primarily through paracrine signaling.

Key Pathways and Quantitative Data

The table below summarizes the primary angiogenic factors and their measured effects in stem cell therapy for MI.

Table 1: Key Angiogenic Factors and Their Effects in Stem Cell Therapy for MI

| Factor / Pathway | Biological Effect | Measured Outcome in MI Models | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| VEGF/VEGFR2 | Promotes endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and survival; increases vascular permeability. | Increased vessel density; improved perfusion of ischemic tissue. | [21] [22] |

| Paracrine Secretion (VEGF, FGF, HGF) | MSCs release growth factors that promote angiogenesis and ameliorate the ischemic microenvironment. | Increased left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) by 3.8% in clinical trials. | [14] |

| SDF-1α | Chemokine that recruits endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) to the site of injury. | Enhanced neovascularization and attenuated cardiomyocyte apoptosis. | [14] |

| Exosomal microRNAs (e.g., miR-21, miR-210) | Carried by MSC-derived exosomes; regulate cardiomyocyte apoptosis and fibrosis. | Reduction in infarct size; improved cardiac function. | [14] |

Experimental Protocol: Quantifying Angiogenesis

Objective: To assess the pro-angiogenic potential of stem cell-conditioned medium or transplanted cells in a murine MI model.

Materials:

- Matrigel: Basement membrane matrix for in vitro tube formation assays.

- Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs): Standard cell model for studying angiogenesis in vitro.

- Recombinant VEGF and Anti-VEGF Antibody: Positive and negative controls, respectively.

- CD31 Antibody: For immunohistochemical staining of endothelial cells to quantify vessel density in tissue sections.

Methodology:

- In Vitro Tube Formation Assay:

- Coat a 96-well plate with growth factor-reduced Matrigel (50 µL/well) and allow it to polymerize.

- Seed HUVECs (1x10^4 cells/well) in conditioned medium from cultured MSCs.

- Include control wells with basal medium supplemented with recombinant VEGF (50 ng/mL) or an anti-VEGF antibody (10 µg/mL).

- Incubate for 6-18 hours at 37°C.

- Image the formed capillary-like structures using an inverted microscope.

- Quantify the total tube length and number of master junctions per field of view using image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ with the Angiogenesis Analyzer plugin).

- In Vivo Vessel Density Analysis:

- Induce MI in mice via permanent ligation of the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery.

- Administer stem cells (e.g., 1x10^6 MSCs) via intramyocardial injection into the border zone.

- After 28 days, euthanize the animals and harvest the hearts.

- Fix hearts in 4% paraformaldehyde, embed in paraffin, and section (5 µm thickness).

- Perform immunohistochemical staining with an anti-CD31 antibody to label endothelial cells.

- Count the number of CD31-positive vessels in five random high-power fields (HPF, 200x magnification) from the infarct and border zones.

Data Interpretation: A significant increase in tube length in vitro and vessel density in vivo in treatment groups compared to controls indicates a potent pro-angiogenic effect.

Angiogenesis Signaling Pathway Diagram

Title: Core Angiogenesis Pathway in Stem Cell Therapy

Anti-apoptotic Pathways Activated by Stem Cells

Inhibition of cardiomyocyte apoptosis is a major mechanism by which stem cell therapy preserves cardiac function post-MI. This occurs primarily via paracrine factors that activate pro-survival signaling cascades.

Key Pathways and Quantitative Data

The table below outlines the primary anti-apoptotic mechanisms and their documented effects.

Table 2: Anti-apoptotic Mechanisms of Stem Cells in MI

| Mechanism / Pathway | Biological Effect | Measured Outcome | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paracrine Factors (IGF-1, SDF-1α) | Activate PI3K/AKT pathway, inhibiting pro-apoptotic proteins like BAD and Caspase-9. | Attenuated cardiomyocyte apoptosis; improved functional recovery. | [14] |

| Exosomal microRNAs | miR-21 and miR-210 target pro-apoptotic genes, reducing cell death. | Reduced fibrosis and cardiomyocyte apoptosis in preclinical models. | [14] |

| Akt Overexpression | Genetically engineered MSCs overexpressing Akt enhance cell survival and protective paracrine effects. | Protected myocardium for 72 hours post-transplantation. | [23] |

| Intercellular Material Transport | Stem cells transfer healthy mitochondria to damaged cardiomyocytes via tunneling nanotubes. | Provides bioenergetic support and enhances survival of stressed cells. | [14] |

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Anti-apoptotic Effects

Objective: To evaluate the anti-apoptotic effect of stem cell-derived factors on cardiomyocytes in vitro.

Materials:

- H9c2 Cardiomyoblasts or Primary Neonatal Rat Ventricular Myocytes (NRVMs): Representative cell lines for in vitro apoptosis studies.

- Serum-Free Medium: To simulate ischemic stress.

- Recombinant IGF-1: Positive control for anti-apoptotic signaling.

- Caspase-3/7 Activity Assay Kit: (Luminescent or fluorescent) for quantifying apoptosis.

- TUNEL Assay Kit: For direct labeling of DNA fragmentation in apoptotic cells.

- Phospho-AKT (Ser473) Antibody: For detecting activation of the AKT pathway via Western Blot.

Methodology:

- Induction of Apoptosis and Treatment:

- Culture H9c2 cells or NRVMs in full-growth medium until 70-80% confluent.

- Induce apoptosis by switching to serum-free medium for 24 hours.

- Treat experimental groups with conditioned medium from MSCs. Include controls: negative control (serum-free medium only) and positive control (serum-free medium + 100 ng/mL IGF-1).

- Caspase Activity Measurement:

- After treatment, lyse cells and assay for caspase-3/7 activity according to the manufacturer's protocol.

- Measure luminescence/fluorescence with a plate reader. A decrease in signal indicates inhibition of apoptosis.

- TUNEL Staining:

- After treatment, fix cells with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilize with 0.1% Triton X-100.

- Perform TUNEL staining according to the kit instructions. Counterstain nuclei with DAPI.

- Image five random fields per well using a fluorescence microscope. Calculate the percentage of TUNEL-positive nuclei.

- Western Blot Analysis for AKT Pathway:

- Harvest cells in RIPA buffer. Separate proteins (30 µg per lane) by SDS-PAGE and transfer to a PVDF membrane.

- Probe the membrane with anti-phospho-AKT (Ser473) and total AKT antibodies.

- A significant increase in the ratio of phospho-AKT to total AKT in treated groups indicates pathway activation.

Data Interpretation: A statistically significant reduction in caspase activity and TUNEL-positive cells, coupled with increased AKT phosphorylation, confirms an anti-apoptotic effect.

Anti-apoptosis Signaling Pathway Diagram

Title: Stem Cell Paracrine Anti-apoptotic Signaling

Extracellular Matrix Remodeling in Myocardial Repair

The ECM is not a passive scaffold but a dynamic entity. Post-MI, maladaptive ECM remodeling leads to fibrosis and stiffening, impairing cardiac function. Stem cells contribute to ECM "normalization," which can mitigate adverse remodeling and support repair.

Key Components and Enzymes in ECM Remodeling

The table below catalogues the primary ECM components and remodeling enzymes relevant to the cardiac environment post-MI.

Table 3: Key ECM Components and Remodeling Enzymes in Cardiac Repair

| ECM Component/Enzyme | Role in Normal Heart | Change Post-MI / Role in Remodeling | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collagen I & III | Provides structural integrity and tensile strength. | Increased deposition and cross-linking, leading to fibrosis and increased stiffness. | [24] [25] |

| Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMPs: MMP-2, MMP-9, MMP-14) | Maintain ECM homeostasis via controlled degradation. | Overexpressed; degrade basement membrane (Collagen IV) facilitating adverse remodeling; activity correlates with malignant progression. | [24] |

| Lysyl Oxidase (LOX) | Catalyzes collagen cross-linking for mechanical stability. | Upregulated in hypoxia; increases ECM stiffness, promoting fibrosis and tumor progression. | [24] |

| Fibronectin | Glycoprotein involved in cell adhesion and migration. | Overproduced, contributing to increased ECM rigidity and cell migration. | [25] |

| Hyaluronic Acid | Proteoglycan that maintains tissue hydration and volume. | Accumulates, contributing to desmoplasia and increased stiffness. | [25] |

Experimental Protocol: Analyzing ECM Composition and Stiffness

Objective: To evaluate the impact of stem cell therapy on ECM composition, organization, and stiffness in a mouse MI model.

Materials:

- Picrosirius Red Stain: Specifically stains collagen fibers. When viewed under polarized light, it can differentiate between thin (green/yellow) and thick (orange/red) collagen fibers.

- Masson's Trichrome Stain: Differentiates collagen (blue) from muscle (red).

- Anti-LOX Antibody / Anti-MMP-9 Antibody: For immunohistochemical staining of remodeling enzymes.

- Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) Cantilevers: For direct measurement of tissue stiffness on tissue sections.

Methodology:

- Tissue Preparation:

- Following the in vivo MI model described in Section 2.2, harvest hearts at the study endpoint (e.g., 28 days post-MI).

- Fix a portion of the heart in 4% paraformaldehyde for paraffin embedding and sectioning (5 µm). Flash-freeze another portion for protein analysis.

- Histological Staining and Analysis:

- Picrosirius Red Staining:

- Deparaffinize and hydrate sections. Stain with Picrosirius Red solution for 60 minutes.

- Rinse, dehydrate, and mount. Image under both brightfield and polarized light.

- Quantify the total collagen volume fraction (%) in the infarct area using image analysis software.

- Immunohistochemistry for LOX/MMPs:

- Perform antigen retrieval on deparaffinized sections.

- Incubate with primary antibodies against LOX or MMP-9 overnight at 4°C.

- Use appropriate secondary antibodies and DAB development. Counterstain with hematoxylin.

- Score the staining intensity (0-3) and percentage of positive cells in the infarct and border zones.

- Picrosirius Red Staining:

- Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) for Stiffness:

- Use fresh or optimally preserved tissue sections.

- Use an AFM with a spherical tip cantilever to perform force mapping on the infarct border zone.

- Calculate the Young's modulus (a measure of stiffness) from the force-distance curves. Compare stiffness between treatment and control groups.

Data Interpretation: Successful ECM "normalization" is indicated by a more organized collagen structure, reduced total collagen deposition, decreased expression of pro-fibrotic enzymes (LOX), and a measured reduction in tissue stiffness toward normal values.

ECM Remodeling Pathway Diagram

Title: ECM Remodeling Pathway Post-Myocardial Infarction

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below lists critical reagents for investigating the molecular pathways discussed in this application note.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Key Pathway Analysis

| Reagent / Tool | Specific Example | Primary Function in Experiments | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-CD31 Antibody | Monoclonal anti-mouse CD31 (PECAM-1) | Immunohistochemical staining to identify and quantify endothelial cells and blood vessels. | [21] |

| Recombinant Growth Factors | Recombinant Human VEGF165, Recombinant Human IGF-1 | Used as positive controls in angiogenesis and anti-apoptosis assays to validate experimental systems. | [14] [21] |

| Matrix for Tube Formation | Growth Factor-Reduced Matrigel | Basement membrane extract used as a substrate for in vitro endothelial tube formation assays. | [21] |

| Activity Assay Kits | Caspase-Glo 3/7 Assay | Luminescent assay for sensitive quantification of caspase-3/7 activity as a marker of apoptosis. | [14] |

| Histological Stains | Picrosirius Red | Specific stain for collagen; allows for quantification of fibrosis and analysis of collagen fiber organization under polarized light. | [24] [25] |

| Enzyme Antibodies | Anti-LOX Antibody, Anti-MMP-9 Antibody | Detection and localization of key ECM remodeling enzymes in tissue sections via IHC. | [24] |

| 1-Deoxynojirimycin hydrochloride | 1-Deoxynojirimycin hydrochloride|1-DNJ | Bench Chemicals | |

| Migalastat Hydrochloride | Migalastat Hydrochloride | Research Compound | Migalastat hydrochloride is a pharmacological chaperone for enzyme research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

Translational Techniques: From Cell Harvesting to Clinical Delivery

In the field of regenerative medicine for myocardial infarction (MI), the choice between autologous (using the patient's own cells) and allogeneic (using donor-derived cells) stem cell transplantation is a fundamental consideration for researchers and therapy developers [26]. Each strategy presents a distinct profile of advantages and logistical challenges, impacting therapeutic efficacy, timing, and clinical applicability [1] [26]. Autologous therapies mitigate immune rejection risks but are often limited by the patient's age and health status, which can compromise cell potency and delay treatment [26]. In contrast, allogeneic cells, particularly mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) from sources like umbilical cord tissue, offer an "off-the-shelf" solution with consistent quality and viability, enabling administration during the critical acute or subacute phases of MI recovery [27] [26]. However, they carry a inherent risk of immune complications such as Graft-versus-Host Disease (GVHD) [28] [26]. This document details the standardized protocols for both approaches, providing a framework for preclinical and clinical research in cardiac repair.

Comparative Analysis: Autologous vs. Allogeneic Approaches

The decision between autologous and allogeneic cell sourcing involves balancing critical factors such as immune compatibility, cell viability, production timelines, and suitability for acute treatment windows. The table below summarizes the core characteristics of each approach.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Autologous and Allogeneic Cell Therapies for MI Research

| Characteristic | Autologous Approach | Allogeneic Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Immune Rejection Risk | Negligible; uses patient's own cells [27] | Present; requires HLA typing and matching to minimize risk of GVHD [28] [26] |

| Therapeutic Potential | Limited by patient's age and comorbidities; cell potency may be reduced [26] | High; cells can be screened for optimal viability and potency [26] |

| Cell Sources | Bone marrow, adipose tissue [27] | Donor bone marrow, umbilical cord tissue, umbilical cord blood [28] [27] |

| Production & Readiness | Requires weeks for cell harvesting and expansion; not suitable for acute-phase treatment [26] | "Off-the-shelf" availability; enables treatment in acute/subacute phase [27] [26] |

| Key Challenge | Time-consuming ex vivo expansion; variable cell quality [26] | Risk of immune rejection and GVHD [28] [26] |

| Ideal For | Research on chronic phase MI or personalized medicine approaches [26] | Research requiring standardized, readily available cells for acute MI models [26] |

Quantitative Outcomes in Myocardial Infarction

Clinical and preclinical studies have evaluated the efficacy of stem cell therapy through key cardiac function parameters. The quantitative outcomes, primarily improvements in Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction (LVEF), provide critical evidence for researchers assessing therapeutic potential.

Table 2: Quantitative Outcomes of Stem Cell Therapy in Myocardial Infarction

| Outcome Measure | Reported Improvement | Notes & Context |

|---|---|---|

| LVEF (Echocardiography) | Mean Difference (MD): 2.53% at study end; MD: 3.89% from baseline [29] | High heterogeneity observed (I² = 76%) [29] |

| LVEF (MRI) | MD: 0.83% at study end (not significant); MD: 1.37% from baseline [29] | Considered a more precise imaging modality [29] |

| LVEF (Long-Term) | 2.21% at 12 and 24 months [30] | Data from a meta-analysis of 83 studies (n=7307 patients) [30] |

| Infarct Size | MD: 1.80% at 6 months; MD: 0.70% at 12 months [30] | Measured as a percentage [30] |

| Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events (MACE) | Favorable trend at 6 months (Odds Ratio: -0.89); no significant improvement at 12, 24, or 36 months [30] | Composite endpoint including death, reinfarction, stroke [30] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Autologous Bone Marrow-Derived Mononuclear Cell (BMMNC) Preparation and Intracoronary Delivery

This protocol is widely used in clinical trials for AMI and involves harvesting the patient's own bone marrow, processing it to isolate mononuclear cells, and delivering them via the intracoronary route [29].

Materials:

- Sterile Bone Marrow Aspiration Kit: Including needles and heparinized collection bags.

- Ficoll-Paque PREMIUM: Density gradient medium for cell separation.

- Cell Culture Media: X-VIVO 10 or equivalent serum-free media [29].

- Heparinized Saline: For cell washing and suspension [29].

- Cell Counter and Flow Cytometer: For cell quantification and viability assessment (e.g., CD34+ count) [29].

Procedure:

- Bone Marrow Harvest: Under aseptic conditions and local anesthesia, aspirate approximately 50-100 mL of bone marrow from the patient's iliac crest into a heparinized container to prevent coagulation [29].

- Cell Isolation:

- Dilute the bone marrow sample with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

- Carefully layer the diluted marrow over Ficoll-Paque in a centrifuge tube.

- Centrifuge at 400-500 × g for 30-40 minutes at room temperature with the brake disengaged.

- After centrifugation, aspirate the mononuclear cell layer from the plasma-Ficoll interface.

- Wash the harvested cells 2-3 times with heparinized saline or culture media by centrifugation to remove platelets and residual Ficoll [29].

- Cell Characterization & Formulation:

- Resuspend the cell pellet and perform a cell count and viability assay (e.g., Trypan Blue exclusion).

- Optional: Use flow cytometry to quantify the population of progenitor cells (e.g., CD34+). Doses in clinical trials often range from 50 to 600 million total cells, with CD34+ cell counts around 1-2 million [29].

- Formulate the final product in 10-20 mL of 0.9% normal saline or the patient's own serum for infusion [29].

- Intracoronary Delivery:

- Post-PCI, deliver the cell suspension via an intracoronary balloon catheter.

- Use the stop-flow technique: inflate the balloon to briefly obstruct blood flow and facilitate cell migration into the infarcted tissue.

- The typical infusion time is several minutes, after which the balloon is deflated to restore flow [29].

Protocol 2: Allogeneic Umbilical Cord-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cell (UC-MSC) Preparation and Intravenous Delivery

This protocol outlines the use of an "off-the-shelf" allogeneic MSC product, which is particularly relevant for acute phase research due to its immediate availability [27] [26].

Materials:

- Cryopreserved UC-MSC Vial: Obtained from a certified cell bank, typically containing 10-100 million cells per vial.

- Water Bath: Set to 37°C for rapid thawing.

- Complete Culture Media: Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with fetal bovine serum (FBS) or human platelet lysate.

- Infusion Solution: Plasmalyte A or 0.9% normal saline for final cell formulation [27].

Procedure:

- Cell Thawing and Activation:

- Retrieve a cryopreserved vial of UC-MSCs from liquid nitrogen storage.

- Rapidly thaw the vial by gently agitating it in a 37°C water bath until only a small ice crystal remains.

- Immediately transfer the cell suspension into a pre-filled tube containing warm complete culture media to dilute the cryoprotectant (e.g., DMSO).

- Cell Washing and Formulation:

- Centrifuge the cell suspension at 300 × g for 5-10 minutes to form a pellet.

- Carefully aspirate the supernatant to remove the cryoprotectant.

- Resuspend the cell pellet in the desired infusion solution (e.g., Plasmalyte A). Clinical studies often use doses around 2 million cells per kilogram of body weight [27].

- Perform a final cell count and viability check. Viability should exceed 70-80% for administration.

- Intravenous Infusion:

- Administer the cell suspension via a peripheral intravenous (IV) drip.

- The infusion is typically performed slowly, at a controlled rate (e.g., 1 cc per minute), and is usually completed within 2-3 hours [27].

- Monitor the subject closely during and after infusion for any adverse reactions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Stem Cell Research in MI

| Research Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Ficoll-Paque | Density gradient medium for isolating mononuclear cells from bone marrow or blood [29] | Separation of BMMNCs from other bone marrow components during autologous cell processing [29] |

| Heparinized Saline | Prevents coagulation of blood and bone marrow aspirates during collection and processing [29] | Used as a wash and suspension solution for BMMNCs in intracoronary delivery [29] |

| X-VIVO 10 Media | Serum-free cell culture medium designed for clinical-grade cell expansion [29] | Used as the suspension media for BMMNCs in clinical trials [29] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Gene-editing technology to precisely modify stem cell genomes [1] | Enhancing stem cell properties (e.g., overexpressing CXCR4 to improve myocardial homing) [1] |

| Hydrogel Scaffolds | Biomaterial matrices that provide a 3D support structure for cells [1] [26] | Improving stem cell survival and retention after transplantation into the heart [1] |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies | Kits for cell surface marker identification (e.g., CD34, CD45, CD105) for cell population characterization [29] | Quantifying the percentage of CD34+ progenitor cells in a BMMNC preparation pre-infusion [29] |

| 1-Deoxymannojirimycin hydrochloride | 1-Deoxymannojirimycin hydrochloride, CAS:73465-43-7, MF:C6H14ClNO4, MW:199.63 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2,4-Diacetylphloroglucinol | 2,4-Diacetylphloroglucinol | High Purity | RUO | 2,4-Diacetylphloroglucinol, a key Pseudomonas metabolite. For antimicrobial & anticancer research. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

Visualizing the Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the key experimental workflows for autologous and allogeneic stem cell preparation, highlighting the divergent paths and timeframes.

Diagram 1: Autologous Cell Therapy Workflow. This process is patient-specific and involves a significant ex vivo expansion phase, delaying treatment.

Diagram 2: Allogeneic Cell Therapy Workflow. This 'off-the-shelf' process allows for rapid administration, making it suitable for acute phase research.

The selection between autologous and allogeneic cell sourcing strategies is a critical determinant in the design of myocardial infarction research and therapy development. Autologous transplantation offers immune compatibility but is constrained by logistical delays and variable cell quality from the patient. Allogeneic approaches, particularly using UC-MSCs, provide a standardized, readily available product conducive to treating acute MI, albeit with inherent immunogenic risks that require careful management through HLA-matching [28] [26]. The quantitative data from clinical trials indicate modest but significant improvements in LVEF, affirming the biological activity of cell therapy while highlighting the need for further optimization [30] [29]. Future progress will likely hinge on combining these cellular approaches with advanced biomaterials and gene-editing technologies to enhance cell survival, retention, and reparative function, ultimately improving clinical outcomes for heart failure patients.

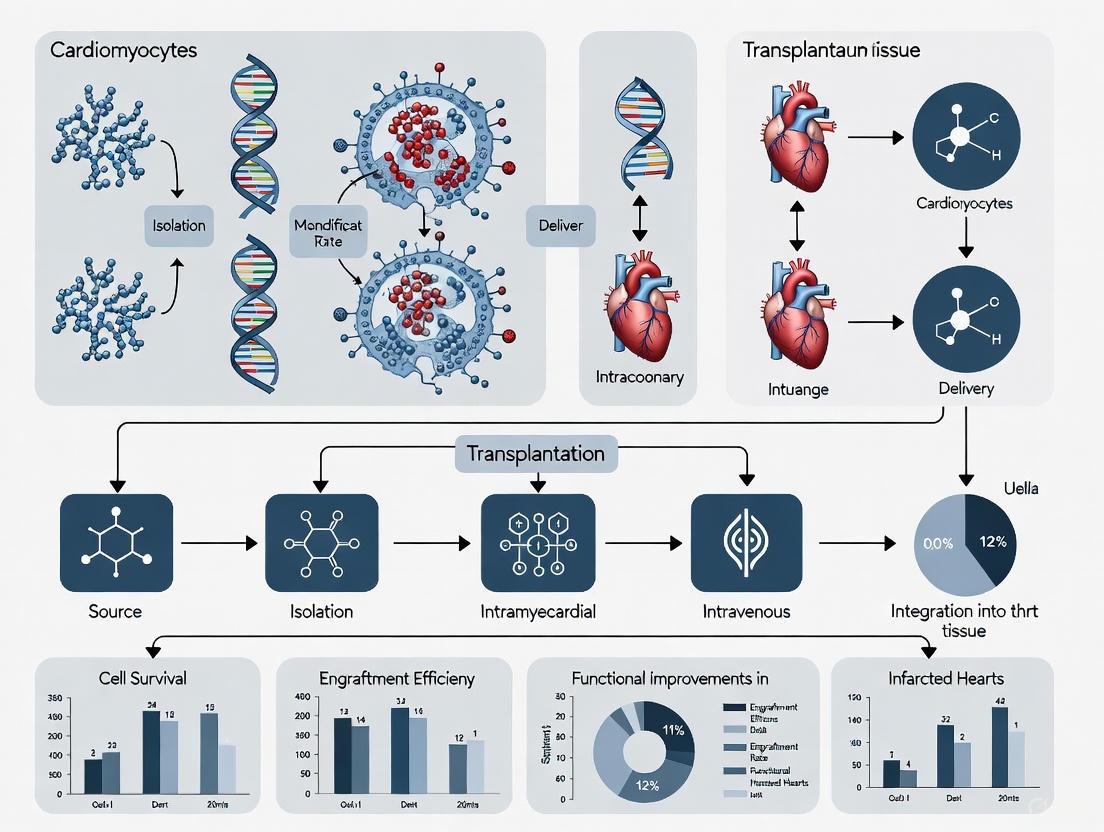

Within the paradigm of stem cell transplantation for myocardial infarction (MI) research, the route of cell delivery is a critical determinant of therapeutic efficacy. The chosen method directly influences cell retention, distribution, and functional integration within the infarcted myocardium [31]. While the therapeutic potential of various stem cells, including mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), is well-documented, their benefits are contingent upon effective targeting to the site of injury [14] [15]. This document delineates the three established delivery methods—intracoronary, intravenous, and intramyocardial injection—providing a structured comparison, detailed experimental protocols, and supporting technical data to inform preclinical and clinical research design.

Comparative Analysis of Delivery Methods

The selection of a delivery method involves balancing factors such as invasiveness, cell retention efficiency, and applicability to acute or chronic MI phases. The table below summarizes the core characteristics of each technique.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Stem Cell Delivery Methods for Myocardial Infarction

| Feature | Intracoronary | Intravenous | Intramyocardial |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Infusion via the coronary artery supplying the infarct zone [32] | Systemic infusion through a peripheral vein [32] | Direct injection into the infarct or border zone [33] [31] |

| Invasiveness | Moderately invasive (requires coronary access) | Minimally invasive | Highly invasive (requires percutaneous or surgical access) |

| Theoretical Cell Retention | Moderate | Low (<5% in some cases [14]) | High [31] |

| Key Advantage | Utilizes existing cardiac catheterization protocols; targets the coronary bed | Simplicity and safety of administration [32] | High local cell concentration; bypasses coronary circulation limitations |

| Primary Limitation | Risk of microvascular occlusion; requires a patent coronary artery [31] | Significant "first-pass" sequestration in lungs/spleen; low cardiac uptake | Potential for procedure-related arrhythmias or perforation; localized injury from needle [31] |

| Typical Clinical Context | Acute MI, post-PCI [34] [32] | Acute MI [32] | Chronic MI/Ischemic Heart Failure [15] [31] |

Method-Specific Application Notes & Protocols

Intracoronary Infusion

Application Notes: This method is most suitable in the acute phase of MI, following reperfusion via primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) [34] [32]. It leverages the existing coronary vasculature to achieve widespread distribution of cells within the infarct territory. The success of this method depends on a patent infarct-related artery and careful control of infusion pressure and volume to minimize the risk of microvascular obstruction, a noted concern with larger cells like MSCs [31].

Detailed Experimental Protocol:

- Cell Preparation: Resuspend the stem cell product (e.g., Bone Marrow Mononuclear Cells - BMMNCs) in a sterile, isotonic solution such as heparinized saline or 0.9% normal saline supplemented with human serum albumin. A typical final volume is 10-20 mL [32].

- Catheterization: Engage the infarct-related coronary artery using a standard guiding catheter.

- Infusion: Position an infusion catheter or an over-the-wire balloon within the target coronary artery. The balloon is inflated at low pressure to occlude blood flow transiently. The cell suspension is slowly infused through the central lumen of the balloon catheter, typically over 2-5 minutes, to allow for capillary transit [32].

- Post-Infusion: After infusion, the balloon is deflated, restoring coronary flow. Monitor the electrocardiogram and the patient for signs of ischemia or arrhythmias during and after the procedure.

Intravenous Infusion

Application Notes: As the least invasive route, intravenous infusion offers a straightforward approach for systemic cell delivery. However, its major drawback is the exceedingly low retention of cells in the heart due to entrapment in the pulmonary capillary bed and other organs [14]. This makes it less efficacious for functional improvement, though it may be suitable for harnessing systemic paracrine effects [14].

Detailed Experimental Protocol:

- Cell Preparation: Prepare cells in a suitable injectable medium like 0.9% normal saline. The final volume can be adapted to standard intravenous infusion bags (e.g., 50-100 mL) [32].

- Infusion: Administer the cell suspension through a peripheral venous line. A standard intravenous infusion set with an in-line filter is used.

- Administration: The infusion is typically conducted slowly, over 30-60 minutes, with continuous monitoring of vital signs.

Intramyocardial Injection

Application Notes: This method is particularly advantageous for treating chronic, ischemic myocardial segments where the coronary vasculature may be compromised, or for delivering larger tissue-engineered constructs [15] [31]. It allows for high local cell density precisely at the site of injury or its border zone. It can be performed surgically (epicardial) or percutaneously (endocardial) using electromechanical mapping systems to guide injections [31].

Detailed Experimental Protocol (Percutaneous):

- Cell Preparation: Concentrate cells in a small volume (e.g., 2.5-5.0 mL) of isotonic buffer with human serum albumin or autologous serum [31].

- Mapping: Using the NOGA XP or a similar system, create a real-time, three-dimensional electromechanical map of the left ventricle to identify the infarct core (characterized by low voltage and poor mechanical function) and the viable border zone [31].

- Injection: Replace the mapping catheter with an injection catheter (e.g., MyoStar). Navigate the injection catheter to the target sites within the border zone. Administer multiple (e.g., 8-12) injections of approximately 0.2-0.5 mL each [31]. The procedure is often guided by a combination of electromechanical and fluoroscopic data.

- Post-Procedural Care: Monitor for complications such as pericardial effusion or ventricular arrhythmias. Echocardiography is recommended post-procedure to rule out pericardial effusion [31].

Diagram 1: Decision workflow for selecting a stem cell delivery method based on the clinical context of myocardial infarction.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Successful execution of stem cell therapy experiments requires standardized reagents and specialized equipment. The following table details key materials used across the featured methodologies.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Stem Cell Delivery Experiments

| Item | Function/Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Bone Marrow Aspirate | Source for autologous stem cells (BMMNCs, MSCs) [31] | Aspirated from the iliac crest under local anesthesia [31] |

| Ficoll Density Gradient | Isolation of mononuclear cells from bone marrow or blood [31] | Used for density gradient centrifugation of bone marrow aspirate [31] |

| Culture Media (ex vivo expansion) | Expansion and maintenance of MSCs [31] | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s low-glucose medium supplemented with Fetal Bovine Serum [31] |

| Trypsin-EDTA Solution | Detachment of adherent cells (e.g., MSCs) from culture flasks [33] | 0.25% trypsin-EDTA solution used to recover MSCs [33] |