Strategic Approaches to Enhance Stem Cell Engraftment: From Foundational Concepts to Clinical Translation

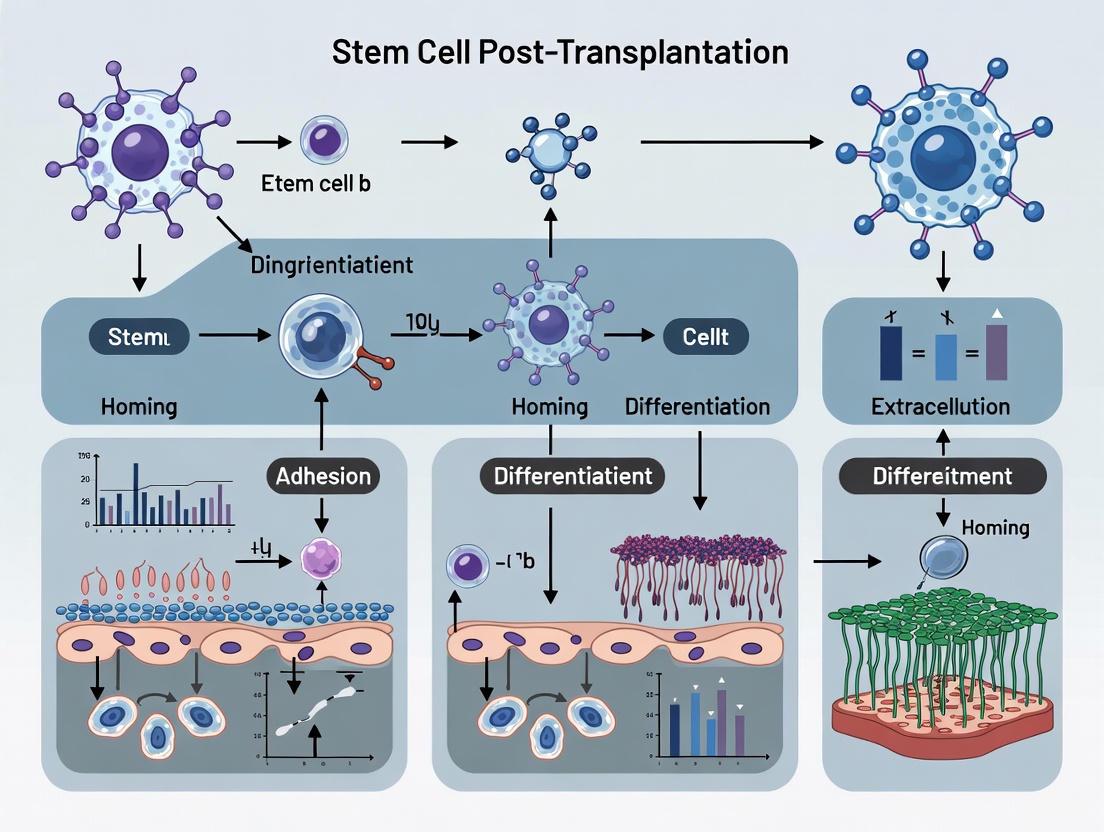

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of current strategies to improve stem cell engraftment post-transplantation, a critical determinant of therapeutic success.

Strategic Approaches to Enhance Stem Cell Engraftment: From Foundational Concepts to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of current strategies to improve stem cell engraftment post-transplantation, a critical determinant of therapeutic success. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational biology, methodological advances, optimization protocols, and validation frameworks. The scope spans from the fundamental mechanisms of homing and survival to the application of pharmacological agents, cellular preconditioning, computational modeling, and comparative efficacy data, offering an integrated perspective on overcoming the translational barrier of low engraftment rates in regenerative medicine.

The Engraftment Challenge: Understanding the Biological Barriers to Stem Cell Survival and Integration

Core Metrics for Engraftment Success

Engraftment success is not defined by a single metric but by a combination of clinical, laboratory, and patient-reported outcomes that provide a comprehensive picture of the therapy's impact [1]. These evaluations assess both short-term and long-term benefits.

The table below summarizes the key quantitative and functional metrics used to define successful engraftment in research and clinical trials.

| Metric Category | Specific Metric | Measurement Method/Tool | Interpretation of Success |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Survival & Kinetics | Cell viability post-transplantation | Bioluminescence imaging, PCR-based cell tracking [2] | High percentage of cells surviving the initial hostile microenvironment; up to 90% can be lost early [2]. |

| Rate of blood cell recovery | Complete Blood Count (CBC) [3] | Sustained neutrophil and platelet count recovery to specific, predefined levels. | |

| Functional Integration | Hematopoietic recovery | Donor chimerism analysis [3] | Establishment of donor-derived hematopoiesis. |

| Tissue-specific function | Organ-specific functional tests (e.g., Echocardiogram for heart function) [4] | Improvement in the functional capacity of the target tissue or organ. | |

| Clinical Endpoints | Overall Survival | Patient follow-up over years [4] | Long-term patient survival post-transplant; e.g., 79% survival rate at 3 years for some hematopoietic transplants [4]. |

| Disease Progression | Clinical assessments, imaging (MRI, PET scans) [4] | Absence of disease recurrence or progression; e.g., reduced risk of heart attack or stroke [4]. | |

| Quality of Life (QoL) | Patient-Reported Outcomes (PROMIS surveys) [3] [4] | Patient-reported improvements in stamina, cognitive function, and social well-being [1] [4]. | |

| Biomarker & Paracrine Activity | Reduction of Inflammation | Biomarker assays (e.g., for IL-6, TNF-alpha) [1] | Significant decrease in systemic inflammatory markers. |

| Promotion of Angiogenesis | Assays for factors like VEGF [2] | Increased secretion of pro-angiogenic factors, indicating active tissue repair. |

Frequently Asked Questions: Troubleshooting Engraftment

What are the primary causes of poor cell survival post-transplantation, and how can they be mitigated?

The hostile transplantation microenvironment is a major contributor to massive cell death, with studies indicating that up to 90% of transplanted stem cells can undergo apoptosis within the first few days [2]. The primary stressors and corresponding mitigation strategies are:

Metabolic Crisis & Ischemia: The lack of immediate vascular connection leads to severe hypoxia and nutrient deprivation [2].

- Troubleshooting Strategy: Implement metabolic preconditioning, such as hypoxic preconditioning (1-5% O₂), which upregulates pro-survival genes (e.g., VEGF, GLUT-1) and antioxidant enzymes, enhancing the cells' anti-apoptotic capacity [2]. Supplementation with oxygen-releasing materials like perfluorocarbon (PFC)-hydrogel systems can also provide temporary metabolic support [2].

Oxidative Stress: The sudden shift from in vitro culture to the damaged tissue site creates a reactive oxygen species (ROS) imbalance [2].

- Troubleshooting Strategy: Use genetic modifications to boost endogenous antioxidant defenses or deliver exogenous ROS-scavenging components alongside the cells [2].

Lack of Physically Supportive Niche: Traditional 2D cell injections do not provide a structured, tissue-like environment.

- Troubleshooting Strategy: Employ 3D culture techniques, such as generating stem cell spheroids or using biomaterial scaffolds. These 3D architectures enhance cell-cell signaling and preserve differentiation potential, leading to better engraftment in vivo [2].

How is successful engraftment measured in clinical trials for different disease areas?

Success is measured through a composite of endpoints tailored to the specific disease.

For Hematological Malignancies (e.g., blood cancers):

For Regenerative Medicine (e.g., joint repair, autoimmune conditions):

For Cardiac Conditions:

- Key Metrics: Reduction in major adverse cardiac events (e.g., one trial showed a 58% reduction in heart attack or stroke risk), improvement in heart function measured by ejection fraction, and reduced hospitalization rates [4].

What patient-specific factors critically influence engraftment success, and how are they screened?

Patient selection is a critical determinant of outcomes. Key eligibility factors and pre-treatment assessments include [4]:

- Overall Health and Comorbidities: Tools like the Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Comorbidity Index (HCT-CI) are used. Patients with a score of 0 (no comorbidities) have significantly better survival rates.

- Inflammation Status: C-reactive protein (CRP) levels are a key biomarker. Normal CRP levels (0-9 mg/L) pre-transplant are associated with better outcomes.

- Donor Age (for allogeneic transplants): A study of 10,000 unrelated donor transplants found that younger donors consistently led to better patient outcomes due to greater regenerative potential of their cells [4].

- Pre-Treatment Workup: This involves comprehensive diagnostic tests, including advanced imaging (X-rays, CT, PET, MRI), and functional assessments of the heart, lungs, and kidneys [4].

Advanced Experimental Protocols for Enhancing Engraftment

Protocol 1: Metabolic Preconditioning of Stem Cells

This protocol aims to enhance stem cell resilience to the ischemic transplant microenvironment.

- Cell Culture: Expand human Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) in standard culture conditions.

- Hypoxic Preconditioning: Place cells in a hypoxic chamber with 1-5% O₂ for 48 hours [2].

- Mechanism: This activates Hypoxia-Inducible Factor (HIF-1α), which upregulates:

- Pro-survival genes (VEGF, GLUT-1).

- Antioxidant enzymes (e.g., SOD2).

- Induces a metabolic shift from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis [2].

- Validation: Preconditioned cells show twice the survival rate under serum-deprived conditions compared to normoxic (20% O₂) controls [2].

Protocol 2: Utilizing 3D Spheroids for Transplantation

3D spheroids mimic the in vivo environment more closely than single-cell suspensions.

- Spheroid Generation: Use low-attachment plates or hanging drop methods to aggregate MSCs into 3D spheroids.

- Advantages: The 3D architecture:

- Preserves multidirectional differentiation potential.

- Enhances cell-cell and cell-matrix signaling.

- Results in cellular characteristics that more closely resemble those observed in vivo, improving survival and integration post-transplantation [2].

- Transplantation: Administer the intact spheroids to the target site using specialized delivery devices.

Research Reagent Solutions for Engraftment Studies

The table below lists key reagents and materials used in advanced engraftment research.

| Reagent/Material | Function in Engraftment Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Perfluorocarbons (PFCs) | Oxygen carriers with high oxygen solubility (15-20x greater than water) to mitigate post-transplant hypoxia [2]. | Incorporated into hydrogel systems to create oxygen-releasing scaffolds that support cell survival in ischemic environments [2]. |

| Calcium Peroxide (CaO₂) | Solid peroxide for sustained oxygen generation via controlled decomposition [2]. | Embedded in PEGDA-based oxygen-producing microspheres to elevate local oxygen levels for 16-20 hours [2]. |

| Hypoxia-Inducible Factor (HIF-1α) Activators | Pharmacological agents to mimic hypoxic preconditioning and upregulate pro-survival pathways [2]. | Used in vitro to pre-condition stem cells before transplantation, enhancing their tolerance to ischemia. |

| ROS-Scavenging Nanoparticles | Mitigate oxidative stress by neutralizing excess Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) at the transplant site [2]. | Co-delivered with stem cells to improve viability by reducing ROS-mediated cellular damage. |

| Engineered Hydrogel Scaffolds | Provide a biomimetic 3D structure that supports cell attachment, protects from physical stress, and can be loaded with biological factors [2]. | Used as a delivery vehicle for stem cells to create large-scale tissue constructs and support vascular ingrowth. |

Strategic Pathways to Enhance Engraftment

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the major challenges in stem cell engraftment and the corresponding strategic solutions.

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: Why are my administered stem cells failing to reach the target tissue in significant numbers?

A: Low homing efficiency is a common challenge, often stemming from poor cell quality or an inadequate chemokine gradient.

- Potential Cause 1: The stem cells were damaged during harvesting or handling. Enzymatic detachment (e.g., with trypsin) can cleave crucial surface receptors like CXCR4, making cells unresponsive to homing signals [6] [7] [8].

- Solution: Use gentler cell dissociation reagents such as TrypLE, Versene, or EDTA-based solutions to preserve surface receptors [7] [8]. Perform a viability assay and check for CXCR4 expression via flow cytometry before infusion.

- Potential Cause 2: The target tissue does not emit a strong enough "homing signal." The key chemokine SDF-1 is often inactivated under normal conditions [9].

- Solution: Prime the target tissue. Strategies include direct injection of a degradation-resistant version of SDF-1 into the injury site [9] or using drugs to keep endogenous SDF-1 active [9].

Q2: My transwell migration assay results are inconsistent. What could be wrong?

A: Inconsistent results often arise from suboptimal assay conditions.

- Potential Cause 1: The cell density seeded in the upper chamber is too high or too low [6] [7].

- Solution: Titrate the cell seeding density. High densities can saturate the membrane pores, while low densities provide insufficient data points. A general starting range is 1x10^5 to 3x10^5 cells/mL [7].

- Potential Cause 2: The cells are proliferating instead of just migrating, skewing the results [7].

- Solution: Serum-starve cells (e.g., using 0.1-1% FBS media) for 24-48 hours before the assay to synchronize the cell cycle and reduce proliferation-driven movement [6] [7]. Alternatively, use a low concentration of Mitomycin C to inhibit proliferation, but be aware of its potential impact on RNA and protein synthesis [7].

- Potential Cause 3: The chemoattractant concentration or migration time is not optimized [6].

- Solution: Always include a positive control (a known potent chemoattractant) and a negative control (no chemoattractant) to benchmark your experimental results [6]. Titrate both the chemoattractant concentration and the incubation time to find the optimal window for your specific cell type.

Q3: What are the proven strategies to enhance the homing efficiency of Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs)?

A: Enhancing homing is a multi-pronged approach focusing on the cell, the target, and the route.

- Strategy 1: Cell Priming and Engineering. Treat MSCs before infusion to make them more responsive. This can be done pharmacologically (e.g., with drugs that stimulate the SDF-1/CXCR4 pathway) [9] or genetically (e.g., by overexpressing CXCR4 or adhesion molecules like VLA-4) [10] [11]. Chemical modification of the cell surface, such as adding specific sugar molecules to enhance binding, is also effective [9].

- Strategy 2: Target Tissue Modification. Increase the "pull" signal from the injury site. As mentioned, this involves upregulating or stabilizing key homing chemokines like SDF-1 at the target tissue [9] [10].

- Strategy 3: Direct Administration. While systemic infusion is common, local implantation or injection of MSCs at the target site (non-systemic homing) bypasses the circulatory system and can significantly improve local cell retention [10].

Key Data and Experimental Outcomes

Table 1: Clinical Impact of MSC Infusion on Engraftment Times

This table summarizes the average engraftment times from a systematic review of 47 clinical studies on using MSCs to accelerate hematopoietic recovery after transplantation [12].

| Hematopoietic Lineage | Average Time to Engraftment (Days) with MSC Co-infusion |

|---|---|

| Neutrophils | 13.96 days |

| Platelets | 21.61 days |

Table 2: Surface Markers and Integrins Critical for MSC Homing

This table details key molecules expressed on MSCs that facilitate the homing process [10].

| Surface Marker/Integrin | Function in Homing Process | MSC Types Where Expressed |

|---|---|---|

| CD44 | Mediates initial tethering and rolling on endothelial cells | BM-MSCs, AT-MSCs |

| VLA-4 (α4β1 integrin) | Binds to VCAM-1 on endothelium; crucial for firm adhesion and transendothelial migration | BM-MSCs, AT-MSCs |

| CD90 (Thy-1) | Associated with MSC identity and immunomodulation | BM-MSCs, AT-MSCs |

| CD73 | Involved in adenosine production and immunosuppression | BM-MSCs, AT-MSCs |

| CXCR4 | Receptor for SDF-1; central for chemotactic activation | BM-MSCs, AT-MSCs |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Transwell Migration Assay for Studying Stem Cell Chemotaxis

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for assessing the migratory capacity of stem cells in response to a chemoattractant [6] [7].

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- Transwell Permeable Supports: Cell culture inserts with a porous membrane that separates upper and lower chambers. Pore size (e.g., 8μm) must be chosen based on the cell type being studied [6].

- Chemoattractant: A chemical signal that induces cell movement (e.g., SDF-1, or media with 1-2% FBS). The concentration must be optimized [6] [7].

- Extracellular Matrix (ECM): For invasion assays, a basement membrane matrix like Corning Matrigel is used to coat the membrane, simulating the in vivo barrier a cell must degrade and invade through [6].

- Cell Dissociation Reagent: Use gentle, non-enzymatic reagents like TrypLE or EDTA to preserve cell surface receptors during harvesting [7] [8].

- Staining Solution: Crystal violet, Diff-Quik, or Calcein AM for fixing and staining migrated cells for quantification [6].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Preparation: Culture and maintain your stem cells, ensuring they are at 60-70% confluency before the assay. Serum-starve cells if necessary to reduce proliferation [7].

- Harvesting: Gently detach cells using a gentle dissociation reagent to preserve surface receptors. Prepare a single-cell suspension in a serum-free or low-serum medium [7].

- Assay Setup: Add the chemoattractant dissolved in medium to the lower chamber of the Transwell plate. For a negative control, use medium without chemoattractant. Seed the cell suspension into the upper chamber insert. Ensure the membrane pores are not submerged in the lower chamber fluid [6].

- Incubation: Incubate the plate at 37°C with 5% CO₂ for the optimized time (e.g., 24-48 hours for migration) [7].

- Quantification:

- For adherent cells: After incubation, gently wipe the non-migrated cells from the top of the membrane with a moist cotton swab. Fix and stain the cells that have migrated to the underside of the membrane. Image and count the stained cells using a microscope. Count multiple fields to ensure a representative average [6].

- For non-adherent cells: Collect the cells that have migrated into the lower chamber and count them using a hemocytometer or flow cytometer [6].

- Analysis: Calculate the percentage of migrated cells relative to the total number of cells seeded or as a fold-change compared to the negative control.

Protocol 2: In Vitro Priming of MSCs to Enhance Homing

This protocol outlines methods to pre-treat MSCs to increase their homing capability post-infusion [9] [10].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Culture MSCs: Expand MSCs (e.g., Bone Marrow-derived MSCs) in standard culture conditions until the desired passage and confluency is reached.

- Priming Treatment: Choose a priming strategy:

- Pharmacological Priming: Incubate MSCs with agents known to stimulate the SDF-1/CXCR4 pathway (e.g., certain drugs as identified in research) [9]. The concentration and duration of treatment require optimization.

- Hypoxic Priming: Culture MSCs under hypoxic conditions (e.g., 1-5% O₂) for a defined period (e.g., 24-72 hours). Hypoxia can upregulate the expression of homing receptors like CXCR4 [11].

- Cytokine Priming: Incubate MSCs with a low dose of specific cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IFN-γ) that are known to enhance the expression of adhesion molecules and chemokine receptors [10].

- Validation: After priming, validate the success of the treatment by checking the surface expression of target receptors (e.g., CXCR4, VLA-4) using flow cytometry.

- Harvest and Infuse: Gently harvest the primed MSCs using a gentle dissociation method and proceed with systemic or local administration.

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Diagrams

Stem cell transplantation holds groundbreaking potential for treating degenerative diseases, tissue injuries, and malignancies. However, clinical outcomes often fall short of expectations, primarily due to the hostile microenvironment that transplanted cells encounter at the target site. Research indicates that up to 90% of transplanted stem cells undergo apoptosis within the initial days post-transplantation [2]. This massive cell loss stems from a complex interplay of metabolic dysfunction, immune-mediated responses, reactive oxygen species (ROS), altered biomechanical rigidity, and disrupted intercellular communication [2]. This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guides to help researchers overcome these critical barriers and enhance stem cell engraftment efficacy.

Troubleshooting Guide: Core Challenges and Solutions

Problem: Poor Cell Survival Due to Metabolic Crisis and Ischemia

- Question: "Why do my transplanted stem cells die so quickly, and how can I extend their viability in ischemic conditions?"

- Background: Transplanted stem cells initially lack vascular connections, leading to a severe interim phase of hypoxia and nutrient deprivation [2]. This metabolic crisis is characterized by insufficient oxygen, glucose, fatty acids, and amino acids, disrupting energy production and waste clearance [2].

- Solutions:

- Metabolic Preconditioning (Stem Cell Domestication): Pre-adapt cells to harsh conditions in vitro before transplantation. Hypoxic preconditioning (1-5% O₂) activates HIF-1α, upregulating pro-survival genes (VEGF, GLUT-1) and antioxidant enzymes. This can double the survival rate of MSCs under serum-deprived conditions compared to normoxic controls [2].

- Oxygen Supplementation: Employ advanced oxygen-delivery systems to bridge the gap until host vasculature integrates.

- Perfluorocarbons (PFCs): Use PFC-hydrogel systems for their high oxygen solubility (15-20 times greater than water) to enhance oxygen-carrying capacity and prolong release [2].

- Peroxide-based Systems: Utilize calcium peroxide (CaO₂) or H₂O₂-releasing nanoparticles for sustained oxygen generation. CaO₂ microspheres can elevate dissolved oxygen in culture media for 16-20 hours under oxygen-glucose deprivation [2].

Problem: Excessive Oxidative Stress Damaging Transplanted Cells

- Question: "How can I protect stem cells from the burst of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the transplantation site?"

- Background: The abrupt transition from optimized in vitro conditions to the pathological oxidative environment of damaged tissues overwhelms the intrinsic antioxidant capacity of stem cells, leading to redox imbalance and death [2].

- Solutions:

- Genetic Modification: Enhance endogenous antioxidant defenses through CRISPR/Cas9 or viral vector-mediated overexpression of genes encoding for antioxidant enzymes like superoxide dismutase (SOD) [2].

- Antioxidant Administration: Deliver ROS-scavenging components directly or via engineered carriers. The use of MitoTempol, a mitochondrial-targeted antioxidant, has been shown to mitigate oxidative stress in MSCs [13].

- Nanoparticle Engineering: Utilize engineered nanoparticles like poly(ethylene glycol)-modified Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles (PZnONPs). In acidic lysosomal environments, these particles release Zn²⁺ and controlled levels of ROS, which can paradoxically enhance stem cell paracrine signaling and improve viability in the inflammatory microenvironment [14].

Problem: Hostile Immune Response and Immune Rejection

- Question: "How can I prevent allogeneic stem cells from being rejected by the host immune system?"

- Background: While MSCs have low immunogenicity, their allogeneic application can still trigger host immune recognition and rejection, primarily mediated by Major Histocompatibility Complex Class I (MHC-I) molecules and pro-inflammatory immune cells [15].

- Solutions:

- CRISPR/Cas9 for Immune Evasion: Create "immune stealth" stem cells by knocking out beta-2 microglobulin (β2M), a crucial subunit of the MHC-I complex. This significantly reduces HLA class I surface expression, evading recognition by alloreactive CD8+ T-cells and improving engraftment [15].

- Preconditioning with Inflammatory Cytokines: Prime MSCs with cytokines like Interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) to enhance their immunomodulatory potency. This upregulates the expression of anti-inflammatory mediators like indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), strengthening their ability to suppress T-cell proliferation [16] [15].

- Biomaterial Encapsulation: Use 3D hydrogel scaffolds or microspheres to create a physical barrier that shields cells from immediate immune attack while allowing nutrient and waste exchange [2].

Problem: Inadequate Paracrine Signaling and Therapeutic Function

- Question: "My stem cells survive but fail to exert sufficient therapeutic effects. How can I boost their paracrine function?"

- Background: The therapeutic benefits of MSCs are largely mediated by their paracrine release of bioactive molecules (growth factors, cytokines, extracellular vesicles). A hostile microenvironment can suppress this essential function [16] [17].

- Solutions:

- Disease Microenvironment Preconditioning (DMP): Precondition MSCs in vitro using serum from diseased animals, specific inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-1β), or high glucose levels to mimic the in vivo target environment. This "primes" the cells, enhancing their secretion of therapeutic paracrine factors and improving outcomes in disease models [16].

- 3D Spheroid Culture: Instead of traditional 2D monolayers, culture MSCs as 3D spheroids. This architecture preserves multidifferentiation potential and enhances cell-cell signaling, resulting in paracrine profiles that more closely resemble those observed in vivo [2].

- CRISPR Enhancement: Genetically engineer MSCs to overexpress key anti-inflammatory and reparative factors such as IL-10 or TNF-alpha stimulated gene/protein 6 (TSG-6), potentiating their innate ability to modulate inflammation and promote repair [15].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most critical factors that make the post-transplantation microenvironment hostile? The core factors form a vicious cycle: 1) Metabolic Crisis (severe hypoxia & nutrient deprivation); 2) Oxidative Stress (excessive ROS); 3) Inflammatory Immune Response (activation of T-cells and macrophages); and 4) Disrupted Cell-Matrix Interactions [2] [13] [18].

Q2: Is autologous or allogeneic stem cell source better for avoiding immune responses? Autologous cells (from the patient) generally avoid immune rejection but are more costly and time-consuming to produce. Allogeneic "off-the-shelf" cells from donors are more practical but carry a higher risk of immune rejection. CRISPR/Cas9 engineering to create hypoimmunogenic allogeneic cells is a promising solution to this dilemma [15].

Q3: Can I simply add antioxidants to the culture medium to protect against oxidative stress? While adding antioxidants to the medium can help in vitro, it offers only transient protection in vivo. More robust strategies include genetically engineering the cells to have a stronger intrinsic antioxidant system or using biomaterials that provide localized, sustained release of antioxidants at the transplantation site [2].

Q4: How long do I need to precondition MSCs for it to be effective? Preconditioning protocols vary, but for hypoxic preconditioning, a common effective duration is 24 to 48 hours [2]. For cytokine preconditioning (e.g., with IFN-γ), priming for 24-72 hours is often used. The optimal time can depend on your specific cell source and target disease [16].

The following table consolidates key quantitative data from recent research to aid in experimental design and comparison of different strategies.

Table 1: Quantitative Data on Strategies to Counteract Hostile Microenvironments

| Strategy | Key Parameter | Reported Outcome | Source/Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypoxic Preconditioning | Cell Survival | 2x higher survival vs. normoxic controls under serum deprivation | MSC study [2] |

| PFC-Hydrogel System | Oxygen Solubility | 15-20 times greater than water | In vitro analysis [2] |

| CaO₂ Microspheres | Oxygen Release Duration | 16-20 hours sustained release under deprivation | SH-SY5Y cells & MSCs [2] |

| β2M Knockout (CRISPR) | T-cell Proliferation | Marked suppression of CD8+ T-cell activation and infiltration | Cardiac repair model [15] |

| PZnONPs-boosted ADSCs | Therapeutic Efficacy | Significant reduction in inflammatory markers and fibrosis in liver | Liver injury model [14] |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists key reagents and their functions for implementing the discussed strategies.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Navigating Hostile Microenvironments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Perfluorocarbons (PFCs) | High-capacity oxygen carrier for incorporation into hydrogels and scaffolds. | Conjugate with hydrogels to improve retention in vivo [2]. |

| Calcium Peroxide (CaO₂) | Solid peroxide for sustained oxygen generation in oxygen-producing scaffolds. | Encapsulate to control release kinetics and local pH changes [2]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Nanoparticle coating to improve dispersion, stability, and reduce toxicity. | Critical for enhancing the bioavailability of delivery systems like PZnONPs [14]. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | Precise gene editing for knockout (e.g., β2M) or knock-in (e.g., IL-10). | Optimize gRNA design and delivery method (lentivirus, electroporation) to MSCs [15]. |

| Interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) | Cytokine for preconditioning MSCs to enhance immunomodulatory potency. | Titrate concentration (e.g., 10-50 ng/mL) and duration (24-72h) to avoid inducing senescence [16] [15]. |

| 3D Hydrogel Scaffolds | Provides 3D architecture for spheroid culture and physical protection from immune cells. | Tune mechanical properties and incorporation of biological factors to mimic target tissue [2]. |

Visualizing the Hostile Microenvironment and Strategic Countermeasures

The following diagram illustrates the major stressors in the hostile microenvironment and the corresponding strategic approaches to enhance stem cell survival and function.

Strategic Countermeasures Against Hostile Microenvironment Stressors

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Hypoxic Preconditioning of MSCs

- Objective: To enhance MSC resilience to in vivo ischemia.

- Materials: MSC culture, standard culture medium, hypoxia chamber or workstation, gas mixture (1-5% O₂, 5% CO₂, balanced N₂).

- Procedure:

- Culture MSCs to 70-80% confluence under standard conditions (37°C, 20% O₂, 5% CO₂).

- Replace the medium with fresh culture medium.

- Place the cells in a hypoxia chamber pre-equilibrated with the desired gas mixture (e.g., 1% O₂).

- Incubate for 24 to 48 hours at 37°C.

- After preconditioning, harvest the cells using standard trypsinization for immediate transplantation.

- Validation: Assess upregulation of HIF-1α via Western blot or increased expression of VEGF and GLUT-1 via qPCR [2].

Protocol: CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated β2M Knockout in MSCs

- Objective: To generate hypoimmunogenic MSCs by eliminating surface MHC-I expression.

- Materials: MSCs, sgRNA targeting the β2M gene, Cas9 expression plasmid or ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex, transfection reagent (e.g., lipofectamine) or electroporator, flow cytometry antibodies for β2M/HLA-I.

- Procedure:

- Design: Design a sgRNA targeting an early exon of the human β2M gene.

- Delivery: Transfect MSCs with the Cas9/sgRNA construct using a high-efficiency method like nucleofection.

- Selection & Expansion: Culture transfected cells and allow them to recover for 48-72 hours.

- Clonal Selection: Use single-cell sorting or dilution cloning to isolate clonal populations.

- Screening: Screen clones for β2M knockout efficiency via flow cytometry using an anti-HLA-ABC antibody.

- Validation: Validate successful knockout by Sanger sequencing of the target site and perform functional assays to confirm evasion of CD8+ T-cell recognition [15].

### Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Poor Engraftment in HSCT Research

Q1: How does donor age influence engraftment success and graft-versus-host disease (GvHD)?

Donor age is a critical, independent risk factor for transplantation outcomes. Utilizing younger donors is consistently associated with improved engraftment and lower rates of GvHD, primarily due to enhanced immune reconstitution and better hematopoietic stem cell fitness [19].

- Experimental Evidence: A recent 2025 analysis of European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) registry data compared outcomes for patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) receiving grafts from younger haploidentical donors versus older mismatched unrelated donors, and vice versa, in the context of post-transplantation cyclophosphamide (PTCy) prophylaxis [19]. The key quantitative findings are summarized below:

Table 1: Impact of Donor Age on Transplant Outcomes with PTCy Prophylaxis [19]

| Donor-Recipient Pairing Comparison | Risk of Grade II-IV Acute GvHD | Risk of Non-Relapse Mortality (NRM) | 2-Year Overall Survival |

|---|---|---|---|

| Younger Haploidentical (<35 yrs) vs. Older Mismatched Unrelated (≥35 yrs) | Significantly Lower | No Significant Difference | No Significant Difference |

| Younger Mismatched Unrelated vs. Older Haploidentical | Significantly Lower | Significantly Lower | No Significant Difference |

- Underlying Mechanism: The superior outcomes with younger donors are attributed to a higher proportion of naïve T-cells, improved functionality of donor-derived T- and NK-cells, increased hematopoietic stem cell number, and a lower risk of transferring clonal hematopoiesis [19].

- Protocol Recommendation: For researchers designing preclinical or clinical studies, donor age should be treated as a key variable. Prioritize the use of younger donor cells when comparing other intervention arms. The data suggests that the benefit of a young donor may even supersede a one-allele mismatch in HLA compatibility [19].

Q2: What conditioning regimen strategies can rescue patients from primary graft failure (PGF)?

PGF is a life-threatening complication with limited salvage options. The choice of a second conditioning regimen for a rescue transplant is crucial, as these patients are often critically ill from prolonged cytopenias [20] [21]. Recent evidence points to the efficacy of shorter, less intensive regimens containing T-cell depleting agents.

- Experimental Evidence: A 2025 retrospective study compared two conditioning regimens for second HSCT in 19 patients with PGF [20] [21]. The outcomes favored a novel 1-day regimen over a multi-day reduced-intensity regimen.

Table 2: Outcomes of Second HSCT for PGF by Conditioning Regimen [20]

| Outcome Measure | 1-Day Regimen (Fludarabine, Cyclophosphamide, Alemtuzumab, low-dose TBI) | Multi-Day RIC (Fludarabine, Busulfan, 2 Gy TBI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neutrophil Engraftment (Cumulative Incidence at Day +28) | 82% | 50% | P = 0.22 |

| Platelet Engraftment (by Day +28) | 70% | 54% | P = 0.61 |

| Day +100 Non-Relapse Mortality (NRM) | 30.3% | 62.5% | P = 0.12 |

| 12-Month Overall Survival (OS) | 53.3% | 37.5% | P = 0.29 |

- Protocol: 1-Day Conditioning Regimen: The successful regimen involved the administration of fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, alemtuzumab, and low-dose total body irradiation (TBI) over a single day [20]. This approach was well-tolerated and resulted in no incidents of grade III-IV acute or chronic GvHD [20].

- Research Implication: For investigators studying graft failure models, this highlights the potential of alemtuzumab-based, T-cell depleting protocols to create immune space and facilitate engraftment without the excessive toxicity of traditional regimens.

Q3: Can mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) co-infusion accelerate hematopoietic recovery, particularly platelet engraftment?

Yes, the adjunctive infusion of MSCs is a promising strategy to mitigate delayed hematopoietic recovery, a significant challenge in haploidentical and unrelated donor transplants [22]. A 2025 systematic review of 47 clinical studies (total n=1,777 patients) provides robust evidence that MSC co-transplantation is safe and effective in accelerating engraftment, with a particularly pronounced effect on platelet recovery [22].

- Mechanism of Action: MSCs support engraftment through multiple pathways:

- Secretion of Hematopoietic Cytokines: They release key factors like stem cell factor (SCF), thrombopoietin (TPO), IL-6, and TGF-β [22].

- Support of the Bone Marrow Niche: MSCs help create a more favorable microenvironment for donor HSCs to implant and proliferate [22].

- Immunomodulation: They modulate T-cell-mediated responses, which may reduce host-versus-graft reactions and support engraftment [22].

- Experimental Workflow: The typical protocol for MSC co-infusion in clinical studies involves:

- MSC Source & Expansion: MSCs are isolated from sources like bone marrow (BM), umbilical cord (UC), or Wharton's jelly (WJ) and expanded ex vivo [22].

- Dosing & Administration: A common dose is (1-2 \times 10^6) MSCs per kg of recipient body weight. The MSCs are usually infused intravenously either at the time of the HSC transplant or within a few days post-transplant [22].

- Outcome Monitoring: Key endpoints include time to neutrophil recovery (Absolute Neutrophil Count > (0.5 \times 10^9/L)), time to platelet recovery (Platelet Count > (20 \times 10^9/L) without transfusion), and incidence of GvHD [22].

### Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Engraftment Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Post-Transplant Cyclophosphamide (PTCy) | Selective in vivo T-cell depletion; prevents GvHD and graft rejection [19]. | Central to modern HLA-mismatched transplant protocols; dosing and timing are critical variables. |

| Alemtuzumab | Anti-CD52 monoclonal antibody; causes profound T-cell depletion [20]. | Used in conditioning regimens to reduce host immunity and prevent rejection, e.g., in salvage transplants for PGF [20]. |

| Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | Adjunct cellular therapy; supports niche function and provides immunomodulation [22]. | Source (BM, UC), passage number, and dose are key experimental parameters affecting efficacy. |

| Fludarabine | Purine analog; immunosuppressive chemotherapeutic agent [20]. | Foundation of many reduced-intensity conditioning regimens. |

| Busulfan | DNA alkylating agent; myeloablative chemotherapeutic [20]. | Used in conditioning; therapeutic drug monitoring is often required due to narrow therapeutic index. |

### Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Is a younger haploidentical donor preferable to an older matched sibling donor? A: Emerging evidence suggests that for patients over 50 with AML, using a younger matched unrelated donor was associated with decreased relapse risk and improved disease-free survival compared to an older matched sibling donor [19]. The field is moving towards prioritizing donor age as a key factor, sometimes even over a minor HLA mismatch [19].

Q: Why is platelet engraftment often more delayed than neutrophil recovery? A: Megakaryopoiesis (platelet production) is a complex process that is typically more protracted than myeloid lineage recovery post-transplant [22]. This prolonged thrombocytopenia is a major clinical challenge and a key reason for investigating supportive therapies like MSC co-infusion [22].

Q: Are MSCs safe to use in clinical trials? A: The 2025 systematic review concluded that MSC co-infusion is generally safe and well-tolerated, with no major safety concerns or increased risk of malignant relapse reported across 47 studies [22]. Their low immunogenicity makes them suitable for allogeneic use [22].

Practical Strategies for Improved Engraftment: Pharmacological, Cellular, and Engineering Solutions

Technical Support Center

This technical support center provides resources for researchers utilizing Thrombopoietin Receptor Agonists (TPO-RAs) in the context of stem cell transplantation and hematopoietic research. The following guides and FAQs address common experimental challenges.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key pharmacological differences between Avatrombopag and recombinant human Thrombopoietin (rh-TPO) that I should consider for my in vitro studies?

A1: The primary differences lie in their mechanism of action, molecular structure, and downstream signaling kinetics. Avatrombopag is a small, non-peptide molecule that binds to the transmembrane domain of the TPO receptor (c-Mpl), while rh-TPO is a large, glycosylated protein that mimics endogenous TPO by binding to the extracellular domain. This leads to differences in signaling duration and potential for antibody generation.

Key Differences Table:

| Feature | Avatrombopag | rh-TPO |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Type | Small molecule, orally bioavailable | Large protein, requires parenteral administration |

| Binding Site | Transmembrane domain of c-Mpl | Extracellular domain of c-Mpl |

| Signaling Profile | Sustained, prolonged JAK2/STAT5 activation | Transient, pulsatile JAK2/STAT5 activation |

| Risk of Neutralizing Antibodies | Negligible | Possible, can cross-react with endogenous TPO |

| Half-life | ~19 hours (in vivo) | ~20-40 hours (in vivo) |

Q2: In our mouse model of hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) transplantation, we are not observing a significant improvement in platelet engraftment with Avatrombopag treatment. What could be the issue?

A2: This is a common troubleshooting point. Several factors could be at play:

- Dosing and Timing: The efficacy of TPO-RAs is highly dependent on the dosing schedule. Administration should begin after transplantation to avoid stimulating residual malignant cells in the host and continue through the nadir period. Verify your dosage against recent literature (e.g., 6 mg/kg daily via oral gavage in mice).

- Drug Formulation: Ensure the Avatrombopag is properly formulated for in vivo use, typically in a vehicle containing substances like DMSO, PEG400, and Tween-80.

- Model Specificity: The response can vary based on the transplant model (e.g., congenic vs. xenogeneic, conditioning regimen intensity). Confirm that your model is appropriate for testing platelet recovery.

- Endpoint Analysis: Ensure you are tracking platelet counts frequently enough (e.g., every 2-3 days) to capture the kinetic difference. Consider also analyzing bone marrow for megakaryocyte colony-forming units (CFU-Mk) at endpoint.

Q3: For expanding CD34+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) in vitro, what is the recommended concentration of rh-TPO to use in a serum-free medium, and how does it compare to Avatrombopag?

A3: For rh-TPO, a concentration of 20-100 ng/mL is standard in serum-free media formulations (e.g., StemSpan SFEM) alongside other cytokines like SCF and FLT3-L. For Avatrombopag, which is cell-permeable, a typical working concentration ranges from 0.5 to 5 µM. It is critical to perform a dose-response curve for your specific cell source, as potency can vary. Note that Avatrombopag may require dissolution in DMSO (keep final concentration <0.1%).

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing TPO-RA Efficacy in a Mouse HSC Transplantation Model

Objective: To evaluate the impact of Avatrombopag or rh-TPO on the kinetics of platelet reconstitution post-transplantation.

Materials:

- Mice: Lethally irradiated recipient mice (e.g., C57BL/6) and donor bone marrow cells.

- TPO-RAs: Avatrombopag (or vehicle control) and/or rh-TPO (or PBS control).

- Equipment: Flow cytometer, hematology analyzer, oral gavage needles, injection supplies.

Methodology:

- Transplantation: Irradiate recipient mice (e.g., 9.5 Gy). Within 24 hours, transplant a defined number of donor bone marrow cells (e.g., 5 x 10^5) via tail vein injection.

- Drug Administration:

- Begin treatment 24 hours post-transplantation.

- Avatrombopag Group: Administer daily via oral gavage (e.g., 6 mg/kg in appropriate vehicle).

- rh-TPO Group: Administer via intraperitoneal or subcutaneous injection (e.g., 10 µg/kg daily).

- Control Group: Administer vehicle only.

- Continue treatment for 21-28 days.

- Monitoring:

- Collect peripheral blood via retro-orbital bleed or tail vein every 3-4 days.

- Analyze platelet counts using a hematology analyzer.

- At endpoint (e.g., day 28), sacrifice mice and analyze bone marrow and spleen for cellularity and progenitor cell content (e.g., by CFU assays and flow cytometry for Lin⁻Sca-1⁺c-Kit⁺ (LSK) cells).

Protocol 2: In Vitro Megakaryocyte Differentiation from Human CD34+ HSPCs

Objective: To differentiate human CD34+ cells into megakaryocytes using a cytokine cocktail including a TPO-RA.

Materials:

- Cells: Human CD34+ HSPCs (cord blood or mobilized peripheral blood).

- Media: Serum-free expansion medium (e.g., StemSpan SFEM II).

- Cytokines: SCF, IL-6, IL-9, TPO (or Avatrombopag/rh-TPO).

- Reagents: FITC-conjugated anti-CD41a and PE-conjugated anti-CD42b antibodies for flow cytometry.

Methodology:

- Culture Initiation: Seed CD34+ cells at 1-2 x 10^5 cells/mL in SFEM II.

- Cytokine Supplementation:

- Control Group: Add SCF (50 ng/mL), IL-6 (10 ng/mL), IL-9 (10 ng/mL).

- TPO-RA Groups: Add the same base cytokines plus either:

- rh-TPO (50 ng/mL)

- Avatrombopag (1 µM, from a 10 mM DMSO stock)

- Culture Maintenance: Maintain cultures at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 12-14 days. Perform half-medium changes with fresh cytokines every 3-4 days.

- Analysis:

- Flow Cytometry: Harvest cells at days 7, 10, and 14. Stain with CD41a and CD42b antibodies to identify megakaryocyte commitment (CD41a⁺CD42b⁺).

- Morphology: Prepare cytospin slides and stain with May-Grünwald Giemsa to identify large, polyploid megakaryocytes.

Signaling Pathway Visualization

Diagram 1: TPO-RA Signaling via c-Mpl

Title: TPO-RA c-Mpl Signaling Pathway

Diagram 2: HSC Engraftment Enhancement Workflow

Title: TPO-RA Enhances HSC Engraftment

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions for TPO-RA Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Recombinant Human TPO (rh-TPO) | Glycosylated protein cytokine; the gold standard for activating c-Mpl in in vitro assays. Used for megakaryocyte differentiation and colony-forming unit (CFU) assays. |

| Avatrombopag (Small Molecule) | Orally bioavailable TPO-RA; useful for in vivo studies and in vitro applications where a protein-free or prolonged signaling stimulus is desired. |

| c-Mpl (TPO Receptor) Antibodies | For detecting receptor expression and phosphorylation via flow cytometry (surface) or Western blot (total). |

| Phospho-STAT5 (Tyr694) Antibodies | Critical for confirming pathway activation downstream of c-Mpl via flow cytometry or immunofluorescence. |

| Serum-Free Expansion Media (e.g., StemSpan) | Defined, serum-free media optimized for the culture and expansion of human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. |

| MethoCult Media | For semi-solid colony-forming unit (CFU) assays to quantify megakaryocyte progenitors (CFU-Mk). |

| CD41a / CD42b Antibodies | Flow cytometry antibodies to identify and quantify committed megakaryocytes and platelets. |

FAQs: MSC Co-Infusion for Hematopoietic Recovery

1. What is the primary clinical rationale for using MSC co-infusion in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT)? The primary rationale is to overcome delayed hematopoietic engraftment, a significant complication of HSCT that extends neutropenia and thrombocytopenia, increasing risks of severe infections, bleeding complications, and prolonged hospitalization [22]. MSC co-infusion leverages their immunomodulatory and hematopoiesis-supporting properties to accelerate the recovery of neutrophil and platelet counts, thereby reducing these transplant-related risks [22] [23].

2. Through what key mechanisms do MSCs enhance hematopoietic recovery? MSCs enhance engraftment through multiple interconnected mechanisms:

- Secretory Function: They release a diverse array of bioactive molecules, including growth factors and cytokines such as SCF, TPO, IL-6, and TGF-β, which are crucial for supporting the survival and proliferation of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) [22] [17].

- Bone Marrow Niche Support: MSCs contribute to rebuilding the bone marrow microenvironment (niche) that is essential for HSC function and differentiation [22].

- Immunomodulation: They interact with various immune cells (T cells, B cells, dendritic cells) and modulate T-cell–mediated responses, creating a more favorable environment for engraftment and reducing complications like GvHD [17] [23].

- Paracrine Signaling: Much of their therapeutic effect is mediated through paracrine actions, including the release of extracellular vesicles that carry signaling molecules [17] [24].

3. Which engraftment parameter shows the most consistent improvement with MSC co-infusion? Clinical evidence most consistently demonstrates a benefit for platelet engraftment [22] [12]. A systematic review of 47 studies found that MSC co-infusion particularly benefits platelet recovery, with an average time to platelet engraftment of 21.61 days in MSC recipients [12]. This is critical as delayed platelet engraftment is traditionally more prolonged and associated with increased morbidity [22].

4. Is MSC co-infusion safe, and what are the primary safety considerations? Systematic reviews and meta-analyses conclude that MSC infusion is generally safe when quality-controlled cells are used, with no serious adverse events directly attributed to the infusion in controlled clinical trials [23] [12]. The most critical safety consideration is hemocompatibility. MSCs can express procoagulant tissue factor (TF/CD142), and its level varies with the cell source. Testing MSC products for TF/CD142 before clinical administration is recommended to mitigate the risk of thromboembolism [25]. Common, minor side effects can include transient fever, nausea, or chills, often manageable with premedication [26].

5. Does MSC source influence its efficacy in supporting engraftment? Yes, the tissue source of MSCs (e.g., bone marrow, umbilical cord, adipose tissue) can influence their functional properties and efficacy [17] [25]. Bone marrow-derived MSCs (BM-MSCs) are the most extensively studied. Umbilical cord-derived MSCs (UC-MSCs) often exhibit enhanced proliferation and lower immunogenicity [17]. The expression of procoagulant tissue factor also varies by source, impacting product safety [25]. Furthermore, donor age and manufacturing inconsistencies are sources of heterogeneity that can affect clinical outcomes [22] [27].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Challenge 1: Inconsistent Engraftment Outcomes in Preclinical Models

- Potential Cause: Heterogeneity in MSC batches due to donor variability, passage number, or expansion protocols.

- Solution:

- Standardize Characterization: Rigorously characterize MSCs against International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) criteria (plastic adherence, surface marker expression, trilineage differentiation) [17] [25].

- Functional Potency Assays: Implement in vitro functional assays, such as a lymphocyte proliferation suppression assay (mixed lymphocyte culture), to batch-test the immunomodulatory potency of your MSC preparations before in vivo use [24].

- Control Passage Number: Use MSCs at a low passage number (e.g., before passage 5-6) to avoid senescence-related functional decline.

Challenge 2: Poor Cell Survival or Engraftment Post-Infusion

- Potential Cause: The instant blood-mediated inflammatory reaction (IBMIR) triggered upon intravenous infusion, leading to cell death and clearance.

- Solution:

- Hemocompatibility Testing: Quantify the expression of procoagulant tissue factor (TF/CD142) on your MSC product using flow cytometry or ELISA [25]. Select cell sources or batches with lower TF/CD142 expression.

- Consider Alternative Routes: While intravenous is common, investigate intra-bone marrow injection if applicable to your research question, as it may bypass IBMIR and direct cells to the niche [24].

Challenge 3: Lack of Observed Therapeutic Effect

- Potential Cause: Suboptimal dosing or timing of MSC administration.

- Solution:

- Dose Optimization: Perform a dose-escalation study. Common clinical doses range from 1-10 million cells per kilogram [25], but the optimal dose can vary based on the model and MSC source.

- Timing Optimization: The timing of MSC infusion relative to HSC transplantation is critical. Test different time points, such as co-infusion on the same day as HSCs or infusion a few days post-transplant, to identify the most effective window for your specific experimental setup [22] [23].

The table below synthesizes key clinical outcomes associated with MSC co-infusion from systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Table 1: Clinical Outcomes of MSC Co-infusion in Allogeneic HSCT

| Outcome Measure | Impact of MSC Co-infusion | Notes & Context |

|---|---|---|

| Neutrophil Engraftment | Accelerated | Average time to engraftment: ~13.96 days [12]. Effect is significant in both RCTs and non-RCTs [23]. |

| Platelet Engraftment | Accelerated | Average time to engraftment: ~21.61 days [12]. This is the most consistently reported benefit [22] [23]. |

| Acute GvHD (aGvHD) | Trend towards reduction | Some studies show a lower incidence, particularly in HLA-mismatched settings [28], but the overall effect is not always statistically significant [23]. |

| Chronic GvHD (cGvHD) | Reduced | A significant reduction in risk has been observed in meta-analyses [23]. |

| Relapse Rate (RR) | No Significant Increase | MSC co-infusion does not appear to increase the risk of disease relapse [23]. |

| Overall Survival (OS) | Generally No Negative Impact | No significant difference in OS observed in most analyses. A reduced OS was noted in one subgroup (adults with hematological malignancies receiving HLA-identical HSCT) [23]. |

Table 2: Impact of Patient and Transplant Factors on MSC Efficacy

| Factor | Subgroup | Observed Effect of MSC Co-infusion |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Children & Adolescents | More consistent improvements in engraftment, GvHD, and non-relapse mortality [23]. |

| Adults | Less pronounced benefits; may only see reduction in cGvHD [23]. | |

| HLA Match | HLA-nonidentical | Greater benefit observed, with improvements in engraftment and GvHD incidence [23]. |

| HLA-identical | More limited benefits, primarily reduction in cGvHD [23]. | |

| Underlying Disease | Malignancies | Improvements in GvHD and non-relapse mortality [23]. |

| Non-malignancies | Accelerated hematopoietic engraftment [23]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: MSC Co-Infusion in an HSCT Model

Objective: To evaluate the efficacy of human bone marrow-derived MSC co-infusion on the acceleration of platelet and neutrophil recovery in an immunodeficient mouse model of human hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Materials Required:

- MSCs: Human bone marrow-derived MSCs, characterized per ISCT criteria (CD73+, CD90+, CD105+, CD34-, CD45-, HLA-DR-), at passage 3-5 [17].

- HSCs: Human CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells (e.g., from cord blood or mobilized peripheral blood).

- Animals: NOD-scid IL2Rγ[null] (NSG) mice, 8-12 weeks old.

- Reagents: Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), Irradiation equipment, Flow cytometry antibodies (e.g., anti-human CD45, CD41, CD15).

Workflow:

Procedure:

- Mouse Conditioning: Subject NSG mice to sublethal irradiation (e.g., 1-2 Gy) 24 hours before transplantation to create a myelosuppressive environment and niche space.

- Cell Preparation:

- Treatment Group: Mix 1x10^5 human CD34+ HSCs with 1x10^6 human BM-MSCs (a 1:10 ratio) in 200µL of sterile PBS.

- Control Group: Prepare 1x10^5 human CD34+ HSCs in 200µL of sterile PBS.

- Transplantation: Infuse the cell suspensions intravenously via the tail vein into the conditioned mice.

- Post-Transplant Monitoring:

- Peripheral Blood Collection: Collect small blood samples from the retro-orbital sinus or tail vein three times per week for 4-5 weeks.

- Flow Cytometry Analysis: Stain samples with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies to track engraftment:

- Human Engraftment: Anti-human CD45.

- Platelet Reconstitution: Anti-human CD41a (expressed on platelets/megakaryocytes).

- Myeloid/Neutrophil Reconstitution: Anti-human CD15.

- Endpoint Analysis: At the end of the study (e.g., 6-8 weeks), sacrifice the mice and analyze bone marrow from femurs and tibias via flow cytometry for human cell chimerism and histology to assess bone marrow cellularity and architecture.

Key Signaling Pathways in MSC-Mediated Hematopoietic Support

The following diagram illustrates the core molecular mechanisms through which MSCs support hematopoietic recovery, integrating secretory, immunomodulatory, and niche-supportive functions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Investigating MSC Co-Infusion

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experimental Design | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Bone Marrow-Derived MSCs | The primary therapeutic cell product. Source for paracrine factors and immunomodulation. | Verify ISCT criteria (CD73+/90+/105+; CD34-/45-). Use low passage numbers (P3-P5) to maintain potency [17] [25]. |

| CD34+ Hematopoietic Stem Cells | Target cells for transplantation and engraftment analysis. | Source (cord blood, bone marrow, mobilized PB) can influence engraftment dynamics. Purity is critical. |

| Immunodeficient Mice (e.g., NSG) | In vivo model to study human hematopoiesis and engraftment without graft rejection. | Ensure proper conditioning (irradiation) to enable niche opening. Monitor for health post-transplant. |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies | To quantify and characterize human cell engraftment and differentiation in mouse blood and bone marrow. | Essential panels: anti-human CD45 (engraftment), CD41/61 (platelets), CD15/66b (neutrophils), CD33 (myeloid). |

| Tissue Factor (TF/CD142) ELISA Kit | To assess the procoagulant potential and hemocompatibility of the MSC product prior to in vivo use. | A critical safety assay. High TF levels may predict thrombotic risk and poor in vivo survival [25]. |

| Lymphocyte Proliferation Assay Kit | In vitro functional potency assay to test the immunomodulatory capacity of MSCs (e.g., via suppression of PHA-driven or MLR-driven T-cell proliferation). | Correlates with in vivo efficacy. Useful for batch-to-batch quality control [24]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Preconditioning Strategies

Q1: What is the fundamental purpose of preconditioning stem cells before transplantation?

A1: The primary purpose of preconditioning is to enhance the survival, function, and therapeutic efficacy of stem cells after transplantation. Upon infusion, cells face a harsh microenvironment characterized by ischemia, inflammation, and oxidative stress, leading to massive cell death—often over 90% within the first week [29]. Preconditioning uses sublethal stresses or genetic modifications to activate the cells' intrinsic protective and reparative mechanisms before transplantation. This "primes" them to better withstand the hostile host environment, improve their engraftment into target tissues, and amplify their paracrine signaling, which is crucial for tissue repair and immunomodulation [30] [29].

Q2: We are considering hypoxic priming for our MSCs. What is a standard and effective protocol we can follow?

A2: A commonly used and effective protocol involves culturing MSCs at low oxygen tensions for a defined period. Based on recent studies, you can follow this workflow [31]:

- Culture Expansion: Expand your MSCs (e.g., from umbilical cord or adipose tissue) under standard culture conditions (21% O₂, 37°C, 5% CO₂) until they reach 80-90% confluence.

- Hypoxic Priming: Replace the culture medium and place the cells in a hypoxia workstation or multi-gas incubator set to 5% CO₂ and 1-5% O₂ at 37°C. The balance gas is N₂.

- Duration: Maintain the cells under these hypoxic conditions for 24 to 48 hours.

- Harvesting: After the priming period, harvest the cells using a standard enzyme like TrypLE Select for subsequent transplantation or analysis.

Studies have shown that this 5% O₂ preconditioning significantly promotes MSC proliferation and alters their transcriptional profile, enhancing their therapeutic potential without compromising safety in animal models [32] [31].

Q3: Our in vivo experiments show poor survival of transplanted MSCs. What preconditioning strategies can we use to enhance cell survival?

A3: Poor post-transplant survival is a major hurdle. You can explore these three strategy families, which can also be combined:

- Hypoxic Preconditioning: As above, this upregulates pro-survival pathways. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) activation leads to increased expression of survival factors like Bcl-2 and survivin [30] [29].

- Pharmacological Preconditioning: Incubate MSCs with specific drugs before transplantation. Effective agents include:

- Isoflurane: A volatile anesthetic that can enhance MSC survival [30].

- Lipopolysaccharide (LPS): Pre-treatment with low-dose LPS can activate toll-like receptors, leading to a protective phenotype [30].

- Diazoxide: A mitochondrial ATP-sensitive potassium channel opener that mimicks ischemic preconditioning [30].

- Cytokine Priming: Pre-treat MSCs with pro-inflammatory cytokines like Interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α). This polarizes MSCs toward a potent immunosuppressive phenotype, characterized by high expression of Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) and TSG-6, which helps them modulate the local immune response and survive longer [33].

Q4: We are researching cardiac repair. What are key genetic modification targets to enhance stem cell engraftment and function for this application?

A4: For cardiac repair, genetic modifications aim to optimize key steps in the cell therapy process. The table below outlines prime targets based on preclinical studies [34]:

Table 1: Key Genetic Modification Targets for Stem Cell-based Cardiac Repair

| Target Process | Genetic Target / Transgene | Intended Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Survival | Akt (a serine/threonine kinase), Survivin, Bcl-2 | Inhibits apoptosis and increases resistance to oxidative stress in the harsh ischemic myocardial environment [34] [30]. |

| Homing & Engraftment | CXCR4 (Receptor for SDF-1) | Enhances the cell's ability to migrate toward and engraft in the infarcted area, which expresses high levels of SDF-1 [34] [30]. |

| Paracrine Signaling | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) | Boosts secretion of angiogenic factors, promoting the growth of new blood vessels to improve blood supply to the damaged tissue [34]. |

| Immunomodulation | Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) | Increases the cell's capacity to suppress local immune activation and inflammation, creating a more favorable environment for repair [29] [33]. |

Q5: Are there any significant safety concerns associated with preconditioning strategies, particularly hypoxic priming?

A5: Overall, hypoxic MSCs from various tissues have been demonstrated to be safe in animal models regarding parameters like hematopoietic function, proinflammatory cytokine levels, and organ toxicity [32]. However, one critical safety consideration is dose-dependent thrombogenic risk. A recent comprehensive safety assessment revealed that while intravenous injection of hypoxic MSCs at a dose of 50 million cells/kg was safe in mice, injections of higher doses led to intravenous thrombosis and embolism in various organs, ultimately causing animal death [32]. Therefore, rigorous dose-optimization studies are an essential prerequisite for clinical translation.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Inconsistent Results with Hypoxic Preconditioning

- Potential Cause: Fluctuating oxygen levels within the hypoxia incubator.

- Solution: Regularly calibrate the oxygen sensor of your hypoxia workstation. Ensure the chamber door is kept closed as much as possible to maintain a stable low-oxygen environment. Allow sufficient time for the environment to equilibrate after opening.

- Potential Cause: Variations in cell confluency at the time of preconditioning.

- Solution: Standardize the cell confluency (e.g., 80-90%) at the start of the hypoxic exposure to ensure consistent cell-to-cell contact and metabolic state.

Problem 2: Preconditioned MSCs Fail to Show Improved Efficacy In Vivo

- Potential Cause: The preconditioning stimulus is too mild or too severe.

- Solution: Conduct a dose-response curve for your preconditioning trigger. For hypoxia, test a range of O₂ concentrations (e.g., 10%, 5%, 3%) and durations (e.g., 24h, 48h) [31]. For drugs, test a range of concentrations to find the optimal "sweet spot" that provides protection without causing significant death in vitro.

- Potential Cause: The route of administration is not optimal for cell delivery to the target organ.

- Solution: Re-evaluate the delivery method. For example, in kidney transplantation, intra-arterial infusion was effective, while intravenous was not [29]. Consider local vs. systemic delivery routes.

Problem 3: Low Cell Yield or Viability After Genetic Modification

- Potential Cause: Cytotoxicity from the viral vector or transfection reagent.

- Solution: Titrate the viral multiplicity of infection (MOI) or the amount of transfection reagent to find the balance between high transduction efficiency and acceptable cell viability. Include a viability-enhancing agent like a caspase inhibitor in the culture medium during the critical post-transduction period.

Key Signaling Pathways in Preconditioning

The therapeutic benefits of preconditioning are mediated by complex signaling pathways that converge on enhanced survival and function. Hypoxic preconditioning is central, primarily mediated by the stabilization of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1alpha (HIF-1α). The following diagram illustrates the core pathway and its functional outcomes:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Preconditioning and Characterization Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Hypoxia Workstation | Provides a controlled, low-oxygen environment for cell priming. | Essential for consistent hypoxic preconditioning; maintains set O₂ (e.g., 1-5%), CO₂, and temperature. |

| StemMACS MSC Expansion Media | Serum-free, xeno-free media for MSC culture. | Eliminates batch variability and safety concerns of fetal bovine serum (FBS) [32]. |

| TrypLE Select Enzyme | A non-animal origin reagent for cell detachment. | Gentle harvesting of MSCs, preserving cell surface markers and viability [32]. |

| Recombinant Human Cytokines | For pharmacological/cytokine preconditioning. | IFN-γ and TNF-α are used to polarize MSCs toward an immunosuppressive phenotype [33]. |

| Lentiviral/Viral Vectors | For genetic modification of stem cells. | Used to overexpress target genes (e.g., Akt, CXCR4) or for knock-down studies (e.g., GSTO1) [34] [31]. |

| Antibodies for Flow Cytometry | For characterization of MSC surface markers. | Essential kit includes CD90, CD105, CD73 (positive) and CD45/CD34/CD11b (negative) per ISCT guidelines [32] [35]. |

| ELISA Kits | To quantify secretion of paracrine factors. | Measure concentrations of VEGF, HGF, IL-10, etc., in cell culture supernatants to confirm enhanced paracrine profile. |

| CCK-8 Assay Kit | To measure cell proliferation and viability. | A colorimetric assay used to assess the effects of preconditioning on cell growth and health [31]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary biological barriers that limit effective stem cell homing to the bone marrow post-transplantation? Effective homing is limited by several barriers. The hostile bone marrow microenvironment often contains inflammatory cytokines and reactive oxygen species that can damage infused cells [36]. There is often poor migration and invasion into the target niches, and infused cells can face limited persistence due to apoptosis or immune rejection [36]. Furthermore, the loss of key homing receptors on stem cells during ex vivo expansion can reduce their ability to respond to homing signals [37].

Q2: How can bioengineering strategies improve the retention and engraftment of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT)? Bioengineering strategies focus on enhancing the innate properties of MSCs. Pre-conditioning MSCs with inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IFN-γ) can enhance their immunomodulatory and secretory functions [17]. Engineering MSCs to overexpress pro-survival genes (e.g., BCL-2) or specific homing ligands and chemokine receptors (e.g., CXCR4) can increase their resistance to stress and direct them to the bone marrow [37] [38]. Utilizing MSCs as delivery vehicles for therapeutic factors like cytokines (SCF, TPO, IL-6) and extracellular vesicles can directly support the hematopoietic niche and promote recovery [22] [17].

Q3: What are the clinical signs of poor engraftment, and what is Post-Engraftment Syndrome (PES)? Poor engraftment is characterized by persistent neutropenia and thrombocytopenia, leading to increased infection and bleeding risks [22]. Post-Engraftment Syndrome (PES) is a distinct, non-infectious complication that occurs around the time of neutrophil recovery. It is diagnosed using established criteria, as outlined in the table below [39].

Table 1: Diagnostic Criteria for Post-Engraftment Syndrome (PES)

| Criteria Set | Major Criteria | Minor Criteria | Diagnostic Requirement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spitzer (2001) | Non-infectious fever (≥38.3°C); Erythematous rash involving >25% of body surface; Non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema [39] | Hepatic dysfunction; Renal dysfunction; Weight gain ≥2.5%; Transient encephalopathy [39] | ≥3 major criteria, OR 2 major + 1 minor criterion [39] |

| Maiolino (2003) | Fever (≥38°C) without identifiable infectious cause [39] | Skin rash; Pulmonary infiltrates; Diarrhea [39] | 1 major + 1 minor criterion [39] |

Q4: What troubleshooting steps can be taken if in-vitro modified cells show poor viability or function? If cell viability is poor, first review the manufacturing process. Check for apoptosis and optimize transduction protocols if genetic modification is used [36]. Assess the formulation and storage conditions of the cell product, including the cryopreservation medium and freeze-thaw cycle [40]. For functional deficits, conduct in-depth potency assays to measure secretome, immunomodulation, and differentiation capacity against predefined release criteria [17]. Consider using advanced delivery systems, such as targeted nanoparticles or hydrogels, to provide sustained release of supportive factors in vivo [41] [42].

Troubleshooting Guides

Delayed Hematopoietic Recovery

Table 2: Troubleshooting Delayed Platelet and Neutrophil Recovery

| Observation | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Investigations | Corrective & Preemptive Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Persistent thrombocytopenia/neutropenia | Graft failure or poor graft quality [40]; Hostile bone marrow microenvironment [41]; Insufficient stromal support (e.g., low MSC potency) [22] | Monitor chimerism levels; Analyze bone marrow biopsy for cellularity and niche composition; Test MSC potency (e.g., cytokine secretion profile) [22] [40] | Consider MSC co-infusion (see Table 4); Use G-CSF to support neutrophil recovery [22]; Optimize cell dose and viability pre-infusion [22] |

| High infection or bleeding risk | Delayed neutrophil and platelet engraftment [22] | Monitor absolute neutrophil count (ANC) and platelet counts daily [22] | Implement rigorous supportive care (prophylactic antibiotics, platelet transfusions) [22]; Consider MSC co-infusion to accelerate recovery [22] |

Managing Post-Engraftment Syndrome (PES)

Table 3: Identification and Management of Post-Engraftment Syndrome

| Step | Action | Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Differentiate from Infection | Rule out bacterial, viral, or fungal infections through blood cultures, chest imaging, and PCR testing. PES is a diagnosis of exclusion [39]. |

| 2 | Apply Diagnostic Criteria | Use Spitzer or Maiolino criteria (see Table 1) to confirm PES. The onset is typically within 96 hours of neutrophil engraftment [39]. |

| 3 | Initiate Corticosteroid Therapy | Intravenous corticosteroids (e.g., methylprednisolone 1-2 mg/kg/day) are the first-line treatment. Most patients show rapid clinical improvement within 24-48 hours [39]. |

| 4 | Provide Supportive Care | Manage specific symptoms, which may include supplemental oxygen for pulmonary involvement or topical agents for skin rash [39]. |

Experimental Protocols for Enhancing Engraftment

Protocol 1: MSC Co-Infusion to Accelerate Hematopoietic Recovery

Methodology: This protocol is based on a systematic review of clinical studies involving over 1,700 patients [22].

- MSC Source and Preparation: Isolate MSCs from a consented donor source (e.g., bone marrow, umbilical cord). Culture and expand MSCs in vitro, ensuring they meet ISCT criteria (positive for CD73, CD90, CD105; negative for CD34, CD45, HLA-DR) [17]. Passage cells no more than 4-6 times to maintain potency.

- Dosing and Timing: The typical therapeutic dose ranges from 1-5 x 10^6 MSCs per kilogram of recipient body weight [22]. The cells are typically administered via intravenous infusion either on the same day as the HSCT or at the time of engraftment (day 0) [22].

- Quality Control: Prior to infusion, perform tests for viability (should be >90%), sterility (bacterial/fungal), and mycoplasma. Potency can be assessed via a tri-lineage differentiation assay or by measuring the secretion of key cytokines (e.g., SCF, TPO, IL-6) [17].

Rationale: MSCs support hematopoiesis by secreting growth factors (SCF, TPO), promoting angiogenesis, modulating the immune response, and directly supporting the bone marrow niche [22] [17].

Protocol 2: Engineering "Armored" Cells with Enhanced Homing

Methodology: This protocol adapts strategies from CAR-T cell "armoring" for improving stem cell homing and persistence [37].

- Genetic Modification: Use lentiviral or retroviral vectors to transduce stem cells or MSCs with genes of interest.

- Key Transgenes:

- Cytokine Expression: Engineer cells to express IL-15 or IL-7 to promote autonomous survival and proliferation, preventing exhaustion [37].

- Homing Receptor Overexpression: Introduce genes for chemokine receptors like CXCR4 to enhance migration toward SDF-1 gradients in the bone marrow [37] [38].

- Dominant-Negative Receptors: Express a dominant-negative TGF-β receptor (dnTGF-βRII) to make cells resistant to the immunosuppressive effects of TGF-β in the microenvironment [37].

- Validation: Post-transduction, validate transgene expression via flow cytometry or PCR. Confirm enhanced functional capacity in vitro using transwell migration assays towards SDF-1 and cytokine secretion assays [37].

Rationale: This "armoring" approach directly counters major barriers in the transplantation microenvironment, including growth factor deprivation, poor homing, and active immunosuppression [36] [37].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Engraftment Optimization Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | Adjunct therapy to support hematopoietic recovery and modulate immunity [22] [17] | Bone marrow-derived (BM-MSC), umbilical cord-derived (UC-MSC). Must be characterized per ISCT guidelines (CD73+, CD90+, CD105+, CD34-, CD45-) [17]. |

| Homing Peptides | Small peptides used to functionalize cells or delivery systems for targeted tissue homing [38] | Can be identified via phage display. Often cyclic and rich in Cys/Arg. Can be modified (e.g., PEGylated) to enhance stability [38]. |

| Lentiviral Vectors | For stable genetic modification of stem cells to enhance persistence and homing [37] | Used to express armored transgenes (e.g., IL-15, CXCR4, dnTGF-βRII) [37]. |

| Cytokines & Growth Factors | For pre-conditioning cells or as supportive therapy in vivo [37] [17] | SCF, TPO, IL-6, G-CSF, IL-15. Used to enhance cell potency or accelerate blood count recovery [22] [37]. |

| Polymeric Nanoparticles | Advanced delivery system for controlled release of supportive drugs or biomolecules at the niche [41] | Can be functionalized with homing peptides (e.g., bone-targeting peptides) for site-specific delivery [41] [38]. |

Overcoming Translational Hurdles: Protocols for Enhancing Cell Viability and Host Receptivity

FAQ: Core Strategies to Enhance Apoptosis Resistance

What are the main causes of low stem cell survival after transplantation? Transplanted stem cells face a hostile microenvironment that triggers apoptosis. Key stressors include severe hypoxia and nutrient deprivation due to a lack of initial vascular connections [2]. This leads to metabolic crisis and the accumulation of cytotoxic waste [2]. Additionally, cells encounter excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) that exceed their antioxidant capacity, and disruption of cell-matrix interactions can induce a specific type of apoptosis called anoikis ("homelessness") [2] [43].

How can preconditioning stem cells improve their survival? Preconditioning involves exposing stem cells to sublethal stress before transplantation to enhance their resilience. A primary method is hypoxic preconditioning (1-5% O₂ for 24-48 hours), which activates hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-1α) and upregulates pro-survival genes (e.g., VEGF, Bcl-2) and antioxidant enzymes [2] [43]. This reprograms cell metabolism from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis, reducing oxygen consumption and enhancing anti-apoptotic capacity [2]. Studies show this can double survival rates under serum-deprived conditions and improve engraftment by 1.5 to 4-fold in various disease models [2] [43].

Are there strategies that target the transplantation site itself? Yes, making the target tissue more receptive is a complementary strategy. This can involve enhancing vascular reconstruction at the site through cytokine-mediated angiogenesis or using biomaterial scaffolds to support new blood vessel formation [2]. Another approach is using monoclonal antibody-based conditioning to prepare the tissue niche, which, when combined with stem cell mobilization strategies, has been shown to safely enhance donor cell engraftment in mouse models [44].

Troubleshooting Guide: Low Post-Transplantation Engraftment

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|