Strategies for Managing Immune Rejection in Allogeneic Transplantation: From Mechanisms to Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the immune mechanisms and management strategies for rejection in allogeneic transplantation, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Strategies for Managing Immune Rejection in Allogeneic Transplantation: From Mechanisms to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the immune mechanisms and management strategies for rejection in allogeneic transplantation, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational immunobiology of allorecognition, covering innate and adaptive immune pathways, including the roles of T cells, alloantibodies, and the recently defined 'Immunologic Constant of Rejection'. The review critically assesses current and emerging methodologies, from conventional immunosuppression to cutting-edge tolerance induction protocols, gene-editing technologies like CRISPR, and novel nanomaterial-based delivery systems. It further discusses troubleshooting for common challenges such as ischemia-reperfusion injury, drug toxicity, and resistance in non-human primate models, and evaluates validation frameworks through biomarkers, genomic profiling, and comparative clinical outcomes. The synthesis of these facets aims to inform the development of more precise and tolerable therapeutic interventions.

Decoding the Immune Response: Foundational Mechanisms of Allograft Rejection

In transplantation, the immune system recognizes and responds to genetically encoded polymorphisms between a donor and recipient, a process known as allorecognition. This immune activation primarily targets major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules, known in humans as human leukocyte antigens (HLAs), and is a principal driver of graft rejection. T lymphocytes play a central role in this process, recognizing alloantigens through distinct pathways—direct, indirect, and semi-direct allorecognition [1] [2]. Understanding these pathways is fundamental to developing strategies to manage immune rejection in allogeneic transplantation.

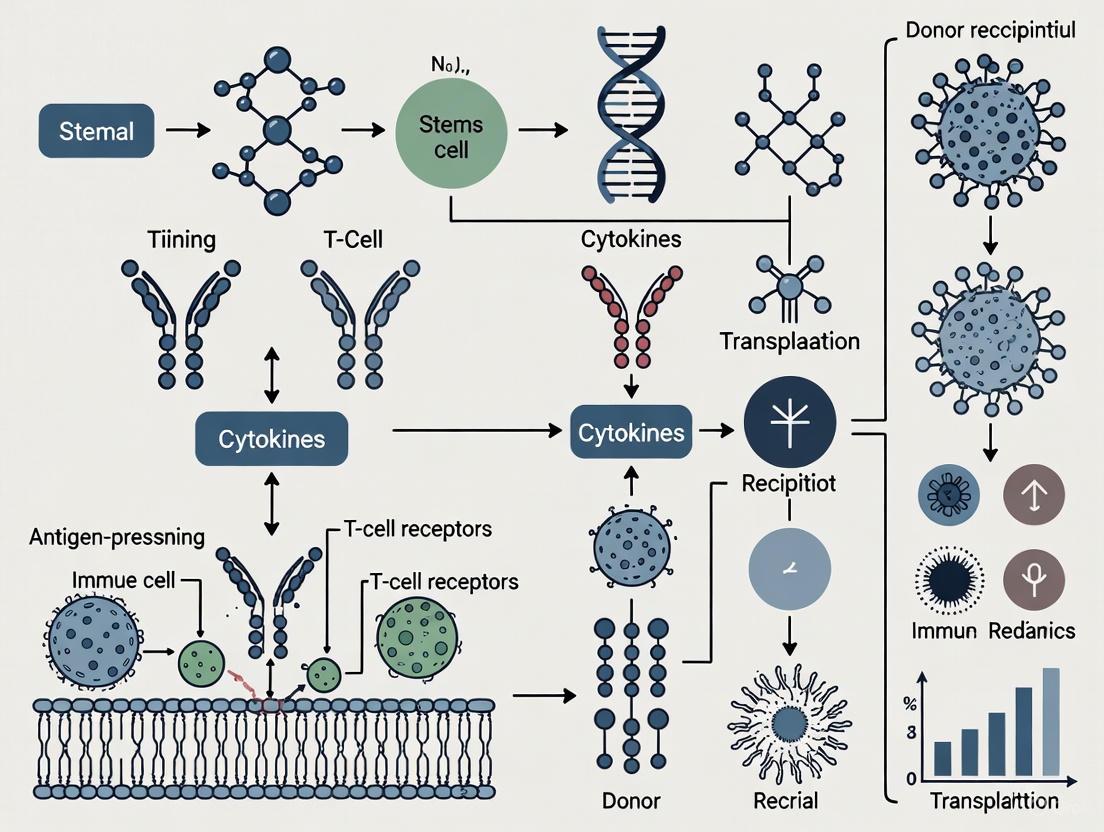

The following diagram illustrates the core cellular interactions and antigen presentation routes in the three principal allorecognition pathways.

Fundamental Concepts: Pathway Mechanisms

Direct Allorecognition

Mechanism: Recipient T cells recognize intact donor MHC molecules (complexed with peptide) presented on the surface of donor antigen-presenting cells (APCs) [1] [2]. This pathway is responsible for the remarkably high frequency of alloreactive T cells (1%-10% of the total T cell repertoire), far exceeding the frequency of T cells responding to conventional antigens [3] [2].

Two non-mutually exclusive models explain the strength of direct allorecognition:

- Multiple Binary Complex Model: The recipient T cell receptor (TCR) recognizes a specific complex of a donor MHC molecule and a particular bound peptide. As each allogeneic MHC molecule can present a vast array of different peptides, this creates numerous foreign complexes for T cells to recognize [3] [4].

- High Determinant Density Model: The TCR interacts directly with polymorphic residues on the donor MHC molecule, largely independent of the bound peptide. In this model, every MHC molecule on the donor cell is recognized as foreign, leading to a very high density of stimulatory ligands [3] [2].

Role in Rejection: The direct pathway is considered the dominant pathway in early acute rejection. Its activation is short-lived, typically lasting only a few weeks post-transplantation, as it depends on the lifespan of donor-derived passenger leukocytes within the graft [1] [4].

Indirect Allorecognition

Mechanism: Recipient APCs phagocytose donor alloantigens, process them into peptide fragments, and present these donor-derived peptides in the context of self-MHC molecules to recipient T cells [1] [2] [4]. This is the same process used for immune responses against conventional pathogens.

Role in Rejection: The indirect pathway is oligoclonal, targeting a limited number of immunodominant epitopes initially, though this can spread to other epitopes over time (epitope spreading) [1] [2]. It is critically important for chronic rejection and for responses against minor histocompatibility antigens, as it can be sustained indefinitely due to the continuous supply of recipient APCs [1] [4].

Semi-Direct Allorecognition

Mechanism: A hybrid pathway where recipient APCs acquire intact donor MHC molecules (via trogocytosis or extracellular vesicles like exosomes) and present them, without processing, to recipient T cells [1] [3] [2]. This allows a single APC to present both intact donor MHC (stimulating direct-pathway T cell clones) and processed donor peptide on self-MHC (stimulating indirect-pathway clones) [1].

Role in Rejection: The semi-direct pathway may help sustain direct-pathway T cell responses beyond the initial post-transplant period, after donor passenger leukocytes have disappeared [1] [3]. It also facilitates cross-talk between CD4+ and CD8+ T cells within a "three-cell cluster" [3].

Table 1: Comparative Features of Allorecognition Pathways

| Feature | Direct Pathway | Indirect Pathway | Semi-Direct Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antigen Presenting Cell (APC) | Donor APC | Recipient APC | Recipient APC |

| Antigen Form Recognized | Intact donor MHC | Donor peptide + Self-MHC | Intact donor MHC on recipient APC |

| Precursor T Cell Frequency | Very high (1-10%) [2] | Low (conventional) [2] | High (same as direct) [1] |

| Duration of Response | Short-lived (weeks) [1] | Long-lived (indefinite) [1] | Potentially sustained [1] |

| Primary Role in Rejection | Acute Rejection [1] [4] | Chronic Rejection [1] [4] | Acute & Chronic Rejection [1] [3] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Experimental Models

Successful investigation of allorecognition pathways relies on specific experimental models and reagents that allow for the isolation and manipulation of immune components.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Models for Allorecognition Studies

| Reagent / Model | Function/Description | Key Application |

|---|---|---|

| TCR Transgenic T Cells | Monoclonal T cells with known specificity for a particular alloantigen [1]. | Tracking the activation, division, and fate of a defined alloreactive T cell population in vivo. |

| MHC Knockout Mice | Donor or recipient mice genetically engineered to lack specific MHC molecules [4]. | Isolating the contribution of direct vs. indirect allorecognition in graft rejection. |

| Mixed Lymphocyte Reaction (MLR) | In vitro co-culture of T cells from one individual with APCs from another [2]. | Measuring the proliferative strength of the direct alloresponse. |

| CTLA-4-Ig (Belatacept) | Fusion protein that blocks CD28-B7 costimulation [5] [6]. | Inhibiting T cell activation; used clinically and in research to promote graft survival. |

| Anti-ICOS Antibodies | Blocking antibodies against the ICOS costimulatory receptor [5]. | Studying the role of ICOS in T cell help for B cells and antibody-mediated rejection. |

| ADAM/MMP Inhibitors | Small molecule inhibitors of metalloproteases [7]. | Investigating the role of LRP1 shedding in the regulation of T cell adhesion and activation. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: Why is the direct T-cell alloresponse so powerful compared to a conventional immune response?

Answer: The extraordinary strength stems from two key factors that greatly amplify the signal:

- High Frequency of Alloreactive T Cells: Between 1% and 10% of an individual's T cell repertoire can recognize a single MHC alloantigen, which is 100 to 1000 times greater than the frequency for a conventional antigen [3] [2].

- High Determinant Density: According to one model, every MHC molecule on a donor APC can be recognized as foreign, creating an immense number of stimulatory ligands on a single cell surface [1] [3].

- Multiple Binary Complexes: A single allogeneic MHC molecule can bind and present a vast array of different peptides. Each unique peptide-MHC combination can be recognized by a distinct T cell clone, massively expanding the number of T cells that can be activated [1] [2].

Troubleshooting Tip for MLR: If your Mixed Lymphocyte Reaction (MLR) shows unexpectedly low proliferation, ensure your donor stimulator APCs are healthy and metabolically active. Use irradiation or mitomycin C treatment to prevent cell division while maintaining surface MHC expression.

FAQ 2: Our in vivo model shows T-cell-mediated rejection even after donor APCs are gone. Which pathway is responsible?

Answer: This is a classic scenario implicating the indirect and/or semi-direct pathways.

- The indirect pathway is the primary suspect for late-phase and chronic rejection. Recipient APCs continuously capture donor antigens from the graft parenchyma, process them, and present donor-derived peptides to T cells indefinitely [1] [4].

- The semi-direct pathway can also contribute. Recipient APCs can acquire and display intact donor MHC molecules, allowing for the continued activation of direct-pathway T cell clones even after the original donor APCs have been cleared [1] [3] [2].

Experimental Protocol to Confirm: To dissect the contribution of each pathway in a mouse transplant model:

- Use donors that are knockout for MHC Class II, eliminating direct recognition of donor MHC II.

- Track the activation of adoptively transferred TCR transgenic CD4+ T cells specific for a donor MHC class I peptide presented by recipient (self) MHC Class II.

- The proliferation and differentiation of these T cells at late time points provide direct evidence of ongoing indirect allorecognition [1].

FAQ 3: We are blocking the CD28-B7 costimulation pathway, but rejection still occurs. What are the potential mechanisms?

Answer: Costimulation blockade can fail due to several redundant and alternative activation pathways:

- Memory T Cells: Alloreactive memory T cells, generated from prior immune challenges (e.g., infections, pregnancies), are less dependent on CD28/B7 costimulation for activation and can mediate rejection [2].

- Alternative Costimulatory Pathways: Other costimulatory molecules can compensate. Key pathways to investigate include:

- ICOS-ICOSL: Critical for T follicular helper (Tfh) cell function, germinal center formation, and alloantibody production [5].

- CD154-CD40: This receptor-ligand pair is crucial for licensing APCs and providing help for CD8+ T cell and B cell responses.

- OX40-OX40L & CD137-CD137L: Members of the TNFR family that enhance T cell survival and effector function [8] [5].

- Heterologous Immunity: Cross-reactive T cells from previous infections (e.g., CMV, EBV) can exhibit "memory" properties and bypass costimulation blockade to initiate rejection [2].

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Problem: Acute rejection despite CTLA-4-Ig treatment.

- Potential Cause 1: Strong pre-existing alloreactive memory T cell response.

- Investigation: Analyze pre-transplant blood for memory T cell markers (CD45RO) and alloreactivity.

- Potential Cause 2: Upregulation of alternative costimulatory pathways.

- Investigation: Isolate graft-infiltrating lymphocytes and analyze expression of ICOS, OX40, and CD137 via flow cytometry. Test combination therapy with anti-ICOS or anti-CD40L antibodies [5].

T-cell Co-stimulation: Beyond the Two-Signal Model

Effective T cell activation requires both an antigen-specific signal (Signal 1 via the TCR) and antigen-non-specific costimulation (Signal 2). The absence of costimulation can lead to T cell anergy or the development of regulatory T cells (Tregs) [5] [7]. The following diagram summarizes the major co-stimulatory and co-inhibitory pathways that shape the alloreactive T cell response.

Key Co-stimulatory & Co-inhibitory Receptors:

- CD28 (Stimulatory): The prototypical costimulatory receptor, constitutively expressed on T cells. Binding to CD80/86 on APCs is critical for naïve T cell activation, IL-2 production, and prevention of anergy [5].

- CTLA-4 (Inhibitory): Binds CD80/86 with higher affinity than CD28, but delivers an inhibitory signal. It functions both through intracellular phosphatase recruitment and via trans-endocytosis, physically removing CD80/86 from APCs [5]. CTLA-4-Ig (Belatacept) is used clinically to block CD28-mediated costimulation [5] [6].

- ICOS (Stimulatory): Induced upon T cell activation, it is crucial for T follicular helper (Tfh) cell differentiation, germinal center formation, and antibody responses. Blocking ICOS can prolong allograft survival in experimental models [5].

- PD-1 (Inhibitory): Expressed on activated and exhausted T cells. Engagement by PD-L1/PD-L2 inhibits T cell function, acting as a critical checkpoint for limiting immune responses [5].

Emerging Concept: An alternative perspective suggests that some forms of co-stimulation may not simply provide a second stimulatory signal. Instead, they may function by inhibiting a constitutive immunosuppressive mechanism. Recent research indicates that ligation of CD28, integrins, and CXCR4 can inhibit metalloprotease-mediated shedding of the Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor-related Protein 1 (LRP1) from the T cell surface. The surface retention of LRP1, in collaboration with thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1), then promotes T cell adhesion and enhances TCR-induced activation [7].

In allogeneic transplantation, the innate immune system is the critical first responder that shapes subsequent adaptive immune responses. The unavoidable processes of organ procurement, preservation, and implantation generate cellular stress and tissue damage, triggering a sterile inflammatory response through the release of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) [9] [10]. These endogenous molecules are recognized by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) on innate immune cells, initiating signaling cascades that lead to the production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines [11] [12]. This initial inflammation, driven particularly by ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI), creates a local microenvironment that enhances alloantigen presentation and can predispose the graft to both acute and chronic rejection [13] [10]. Understanding these mechanisms provides crucial opportunities for therapeutic intervention to improve transplant outcomes.

FAQ: Core Concepts for Researchers

Q1: What are the key DAMPs and PRRs relevant to transplantation research? DAMPs are endogenous molecules released from stressed or dying cells that initiate and perpetuate the innate immune response. Key DAMPs in transplantation include HMGB1, HSPs, extracellular ATP, and mitochondrial DNA [12] [9]. These molecules are recognized by various PRRs, including Toll-like receptors (TLRs), RAGE, and NLRP3 inflammasome components, which are expressed on antigen-presenting cells such as dendritic cells and macrophages [11] [12].

Q2: How does ischemia-reperfusion injury initiate innate immunity? Ischemia leads to cellular metabolic changes including ATP depletion and a switch to anaerobic glycolysis [13]. Subsequent reperfusion causes a burst of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and intracellular calcium overload, resulting in mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening and various forms of regulated cell death such as necroptosis, pyroptosis, and ferroptosis [13] [9]. This cell death releases DAMPs that activate PRR-bearing innate immune cells, initiating a robust inflammatory response [9] [10].

Q3: What are the functional consequences of DAMP-PRR signaling? Engagement of PRRs by DAMPs triggers intracellular signaling pathways, predominantly leading to NF-κB activation and production of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α) and chemokines [11] [12]. This results in increased expression of adhesion molecules, recruitment of innate immune cells (neutrophils, monocytes), and maturation of dendritic cells that can migrate to lymphoid organs to prime alloreactive T cells [11] [10].

Q4: How does innate immunity bridge to adaptive alloimmunity? DAMP-activated innate immune cells, particularly dendritic cells, upregulate costimulatory molecules (CD80, CD86) and MHC molecules, enhancing their antigen-presenting capacity [11]. The inflammatory cytokines produced during IRI promote T-cell differentiation toward proinflammatory Th1 and Th17 phenotypes while impairing regulatory T-cell function, thus shaping the subsequent adaptive immune response against the allograft [13] [10].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Challenge: Differentiating Between Regulated Cell Death Pathways

Problem: In vitro models of IRI show mixed cell death morphologies, making it difficult to identify the predominant pathway.

Solution: Implement a systematic approach using specific inhibitors and markers:

| Cell Death Pathway | Key Mediators | Pharmacological Inhibitors | Experimental Readouts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Necroptosis | RIPK1, RIPK3, MLKL | Necrostatin-1 (RIPK1 inhibitor) | Phospho-MLKL detection by WB, loss of membrane integrity |

| Pyroptosis | Caspase-1, GSDMD | VX-765 (caspase-1 inhibitor) | Caspase-1 activity assay, LDH release, IL-1β secretion |

| Ferroptosis | GPX4 inhibition, lipid ROS | Ferrostatin-1, Liproxstatin-1 | C11-BODIPY assay for lipid ROS, mitochondrial shrinkage |

| Apoptosis | Caspase-3, -8, -9 | Z-VAD-FMK (pan-caspase inhibitor) | Annexin V/PI staining, caspase-3 activation, TUNEL assay |

Table: Strategies for identifying regulated cell death pathways in IRI models. WB: Western blot; LDH: Lactate dehydrogenase; ROS: Reactive oxygen species. [9] [10]

Challenge: Modeling Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury In Vitro

Problem: Standard cell culture systems fail to accurately recapitulate the complex metabolic shifts of IRI.

Solution: Establish a controlled hypoxia-reoxygenation system:

- Ischemia Phase: Place cells in a modular hypoxic chamber (0.5-1% O₂, 5% CO₂, balanced N₂) with glucose-free media for 2-8 hours depending on cell type.

- Reperfusion Phase: Return cells to normoxic conditions (21% O₂) with complete culture media.

- Monitoring: Measure extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) and oxygen consumption rate (OCR) using Seahorse Analyzer to track metabolic shifts from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis and back [13].

- DAMP Detection: Collect supernatant for HMGB1 (ELISA), ATP (luciferase assay), and mitochondrial DNA (qPCR for mitochondrial vs. nuclear genes) at multiple time points post-reoxygenation [12].

Challenge: Assessing PRR Activation and Downstream Signaling

Problem: Difficulty in determining which PRRs are functionally relevant in specific transplant models.

Solution: Employ a combination of genetic and pharmacological approaches:

- Genetic Tools: Use siRNA knockdown or CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing in primary innate immune cells to validate receptor involvement.

- Receptor Blockade: Utilize specific antagonists:

- TLR4: TAK-242 (resatorvid) or Eritoran

- NLRP3: MCC950 or CY-09

- RAGE: FPS-ZM1 or azeliragon [12]

- Signaling Readouts: Monitor NF-κB nuclear translocation by immunofluorescence, MAPK phosphorylation by Western blot, and cytokine production by multiplex ELISA.

Key Signaling Pathways in Innate Alloimmunity

The following diagram illustrates the core signaling pathways connecting DAMPs released during IRI to innate immune activation:

DAMP-PRR Signaling Pathway in Transplant IRI. This diagram illustrates the progression from initial ischemia-reperfusion injury to priming of adaptive immunity, highlighting key points for therapeutic intervention.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table compiles key reagents for investigating innate immunity in transplantation models:

| Category | Specific Reagent | Research Application | Key Findings/Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| DAMP Inhibitors | Glycyrrhizin | HMGB1 inhibition | Reduces IRI, decreases inflammation, improves graft survival in models [12] |

| Ferrostatin-1 | Ferroptosis inhibition | Protects renal tubular cells and islets from ferroptotic death [10] | |

| PRR Antagonists | TAK-242 (Resatorvid) | TLR4 antagonist | Reduces infarct size in MI models, inhibits proinflammatory cytokine production [12] |

| MCC950 | NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor | Decreases infarct size, improves cardiac function in MI models [12] | |

| FPS-ZM1 | RAGE antagonist | Blocks RAGE signaling, reduces inflammation in diabetic models [12] | |

| Cell Death Modulators | Necrostatin-1 | Necroptosis inhibitor (RIPK1) | Reduces necroptosis in IRI models [9] |

| Disulfiram | Pyroptosis inhibitor (GSDMD) | Blocks pore formation, inhibits IL-1β release [9] | |

| Cytokine Targeting | Anakinra | IL-1 receptor antagonist | Reduces inflammation in autoinflammatory diseases [12] |

| Anti-TNF antibodies | TNF neutralization | Used in clinical autoimmune conditions, experimental in transplantation [12] | |

| Metabolic Modulators | 2-DG | Glycolysis inhibitor | Suppresses effector T-cell function, shifts metabolic programming [13] |

Table: Essential research reagents for investigating innate immune mechanisms in transplantation. MI: Myocardial infarction; IRI: Ischemia-reperfusion injury.

Experimental Workflow for Evaluating Innate Immunity in Transplantation Models

The following diagram outlines a comprehensive experimental approach to study innate immunity in transplantation:

Experimental Workflow for Transplant Innate Immunity Research. This workflow outlines key analytical steps from model establishment to outcome assessment, highlighting the iterative process between analysis and therapeutic intervention.

Advanced Technical Considerations

Normothermic Perfusion as an Experimental Platform

Ex vivo normothermic machine perfusion (NMP) and normothermic regional perfusion (NRP) represent advanced platforms for both assessing and modulating innate immune activation prior to transplantation [9]. These systems allow for:

- Real-time biomarker monitoring: Assessment of DAMPs (HMGB1, cell-free DNA) and metabolic parameters in the perfusate as indicators of graft injury [9].

- Therapeutic delivery: Administration of cell death inhibitors (e.g., ferrostatin-1 for ferroptosis) or DAMP-neutralizing agents directly to the organ, potentially mitigating innate immune activation before reperfusion in the recipient [9] [10].

- Gene therapy interventions: Vector delivery (e.g., adenoviral IL-10) during perfusion to modulate the graft's inflammatory profile [10].

Metabolic Reprogramming of Innate Immune Cells

Immunometabolism has emerged as a crucial regulatory layer in innate immunity. During IRI and allograft rejection, innate immune cells undergo metabolic reprogramming:

- Macrophages and DCs shift from oxidative phosphorylation to aerobic glycolysis upon TLR activation, similar to the Warburg effect in cancer cells [13].

- Metabolic inhibitors such as 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG) can suppress proinflammatory macrophage and DC activation, suggesting potential therapeutic applications [13].

- T-cell fate is influenced by the metabolic environment, with glycolytic conditions favoring Th17 differentiation while fatty acid oxidation promotes regulatory T-cell development [13].

Understanding these metabolic checkpoints provides additional opportunities for therapeutic intervention in the innate immune response to allografts.

In allogeneic transplantation, the success of engrafted cells, tissues, or organs is fundamentally governed by the immune recognition of histocompatibility antigens. These antigens are polymorphic proteins that differ between donor and recipient, triggering immune responses that can lead to graft rejection. The major histocompatibility complex (MHC), known as human leukocyte antigen (HLA) in humans, represents the most potent barrier to transplantation, while minor histocompatibility antigens (miHAs) contribute to rejection even in MHC-matched scenarios. Understanding these complex antigen systems is crucial for developing strategies to manage immune rejection in transplantation research and clinical practice.

The MHC is a large gene complex located on chromosome 6p21.3 in humans, containing the most polymorphic genes in the human genome. These genes code for cell surface proteins essential for the adaptive immune system, originally discovered through their role in transplant rejection. Beyond transplantation biology, MHC molecules play a vital physiological role in immune surveillance by presenting peptide antigens to T-cells, enabling discrimination between self and non-self or altered self structures.

MHC Antigens: Major Barriers to Transplantation

Classification and Structure of MHC Molecules

MHC molecules are divided into three main classes based on their structure, function, and genetic localization:

Table 1: Classification of Major Histocompatibility Complex Molecules

| Class | Genes | Structure | Expression | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class I | HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-C | α chain (45 kDa) + β₂-microglobulin (12 kDa) | All nucleated cells | Present endogenous peptides to CD8+ T-cells |

| Class II | HLA-DR, HLA-DQ, HLA-DP | α chain (32-34 kDa) + β chain (29-32 kDa) | Antigen-presenting cells | Present exogenous peptides to CD4+ T-cells |

| Class III | C2, C4, TNF, HSP | Various | Various | Immune regulation, complement proteins |

MHC class I molecules consist of a polymorphic α chain encoded within the MHC locus on chromosome 6 and a non-polymorphic β₂-microglobulin chain encoded on chromosome 15. The α1 and α2 domains form the peptide-binding groove, which accommodates peptides typically 8-11 amino acids in length. MHC class II molecules are heterodimers of α and β chains, both encoded within the MHC region, with the peptide-binding groove formed by α1 and β1 domains that bind longer peptides (13-25 amino acids).

Quantitative Analysis of MHC Polymorphism

The extreme polymorphism of MHC genes represents a significant challenge in transplantation, with thousands of alleles identified for each classical locus:

Table 2: Polymorphism of Human MHC (HLA) Genes

| HLA Locus | Number of Known Alleles | Domain of Polymorphism | Impact on Transplantation |

|---|---|---|---|

| HLA-A | > 7,000 | α1 and α2 domains | High impact for solid organ and stem cell transplantation |

| HLA-B | > 9,000 | α1 and α2 domains | Strongest immunogenicity, highest impact on rejection |

| HLA-C | > 7,000 | α1 and α2 domains | Important for NK cell regulation via KIR interactions |

| HLA-DR | > 3,000 | β1 domain | Dominant role in CD4+ T-cell activation |

| HLA-DQ | > 2,000 | α1 and β1 domains | Important for antibody-mediated rejection |

| HLA-DP | > 1,500 | β1 domain | Lesser immunogenicity but clinically relevant |

This remarkable diversity means that unrelated individuals rarely share identical HLA profiles, necessitating careful donor-recipient matching and aggressive immunosuppression to prevent rejection.

Minor Histocompatibility Antigens

Definition and Clinical Significance

Minor histocompatibility antigens (miHAs) are polymorphic peptides derived from normal cellular proteins that differ between donor and recipient. While individually less immunogenic than MHC molecules, collectively they can stimulate potent immune responses that lead to graft rejection, particularly in HLA-matched hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

These antigens arise from genetic polymorphisms outside the HLA system, including single nucleotide polymorphisms, insertions/deletions, and gene duplications that create protein sequence differences. When processed and presented by MHC molecules, these differential peptides can be recognized as foreign by the recipient's T-cells.

Table 3: Categories and Examples of Minor Histocompatibility Antigens

| Category | Source | Example | Clinical Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Y-chromosome encoded | Male-specific genes | HY antigens | Graft-versus-host disease in female to male transplants |

| Autosomal polymorphisms | Housekeeping genes | HA-1, HA-2 | Graft-versus-leukemia effects, GVHD |

| Tissue-specific | Differentiated cell proteins | Melanocyte antigens | Graft rejection in tissue-specific transplants |

| Mitochondrial | Mitochondrial proteins | MTATP6, MTND | Minor role in solid organ rejection |

Experimental Protocols for Histocompatibility Research

Protocol 1: Mixed Lymphocyte Reaction (MLR) for Alloreactivity Assessment

Purpose: To measure T-cell responses to allogeneic antigens in vitro, predicting potential graft rejection.

Materials:

- Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from donor and recipient

- RPMI-1640 complete medium with 10% FBS

- 96-well U-bottom plates

- Mitomycin C or irradiation source

- [³H]-thymidine or CFSE for proliferation measurement

- ELISA kits for cytokine detection (IFN-γ, IL-2)

Procedure:

- Isolate PBMCs from donor and recipient blood using density gradient centrifugation.

- Treat stimulator cells (donor PBMCs) with mitomycin C (25-50 μg/mL for 30 minutes at 37°C) or irradiation (25-35 Gy) to prevent proliferation.

- Wash stimulator cells three times with PBS to remove mitomycin C.

- Co-culture responder cells (recipient PBMCs) with stimulator cells at a 1:1 ratio (typically 1×10⁵ cells each per well) in 96-well U-bottom plates.

- Include controls: responder cells alone, stimulator cells alone, and third-party PBMCs as positive control.

- Incubate for 5-7 days at 37°C in 5% CO₂.

- Measure proliferation by [³H]-thymidine incorporation (add 0.5-1 μCi/well for the last 18 hours) or CFSE dilution by flow cytometry.

- For cytokine analysis, collect supernatants at day 3-5 for ELISA.

Troubleshooting:

- High background in controls: Optimize mitomycin C concentration or irradiation dose; increase washing steps after treatment.

- Low proliferation response: Check cell viability; optimize cell ratios (test 2:1 or 1:2 responder:stimulator ratios); extend culture duration.

- Variable results: Use fresh PBMCs rather than frozen when possible; standardize donor selection across experiments.

Protocol 2: Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte (CTL) Assay for miHA Responses

Purpose: To detect and quantify recipient T-cell responses against specific minor histocompatibility antigens.

Materials:

- Antigen-presenting cells (APCs) expressing target miHAs

- Candidate miHA peptides

- Recombinant human IL-2

- ⁵¹Cr sodium chromate or LDH cytotoxicity detection kit

- MHC-matched and mismatched target cells

Procedure:

- Generate miHA-specific T-cell lines by stimulating recipient PBMCs with miHA-pulsed APCs weekly for 3-4 weeks.

- Maintain T-cells in complete medium with 20-50 U/mL IL-2.

- Label target cells with ⁵¹Cr (100 μCi per 1×10⁶ cells for 1 hour) or prepare for LDH assay according to manufacturer's instructions.

- Co-culture effector T-cells with labeled target cells at various E:T ratios (40:1, 20:1, 10:1, 5:1) in triplicate.

- Incubate for 4-6 hours at 37°C.

- Measure ⁵¹Cr release in supernatant or LDH activity according to kit instructions.

- Calculate specific lysis: (Experimental release - Spontaneous release) / (Maximum release - Spontaneous release) × 100.

Troubleshooting:

- High spontaneous release: Use healthier target cells; reduce labeling time; use alternative cytotoxicity detection methods.

- Low specific lysis: Confirm MHC restriction of response; optimize T-cell priming conditions; verify miHA expression on target cells.

- Inconsistent results: Standardize target cell preparation; use multiple E:T ratios; include appropriate positive and negative controls.

Allorecognition Pathways: Mechanisms of Graft Rejection

The immune system recognizes allogeneic antigens through several distinct pathways:

Figure 1: Three pathways of allorecognition in transplantation immunology. The direct pathway involves recipient T-cells recognizing intact donor MHC molecules on donor antigen-presenting cells (APCs). The indirect pathway involves recipient APCs processing and presenting donor MHC peptides to helper T-cells. The semi-direct pathway involves recipient APCs acquiring intact donor MHC molecules through extracellular vesicles.

Recent research has revealed additional complexity in allorecognition mechanisms. The inverted direct pathway has been described where donor CD4+ T cells within the graft activate recipient B cells to produce donor-specific antibodies. Furthermore, innate allorecognition by natural killer (NK) cells and monocytes can trigger rejection through MHC-independent mechanisms, including the "missing self" recognition where NK cells activate against cells lacking self-MHC class I molecules [14] [15].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Histocompatibility Investigations

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| MHC Tetramers | HLA-A02:01/NY-ESO-1, HLA-B27:05/EBV | Detection of antigen-specific T-cells | Require precise MHC-peptide combination; validate with positive controls |

| Antibody Panels | Anti-CD3, CD4, CD8, CD45, HLA-DR, CD19, CD56 | Immune cell phenotyping | Include viability dyes to exclude dead cells; titrate for optimal signal |

| Cytokine Assays | IFN-γ ELISpot, Luminex multiplex arrays, intracellular staining | Functional T-cell analysis | Use PMA/ionomycin as positive control; establish background thresholds |

| Blocking Antibodies | Anti-MHC I (W6/32), Anti-MHC II (CR3/43), Anti-CD4, Anti-CD8 | Pathway inhibition studies | Confirm specificity with isotype controls; test multiple concentrations |

| Gene Expression | HLA sequencing primers, KIR genotyping assays | Genetic compatibility assessment | Include quality control for low-resolution and high-resolution typing |

| Antigen Presentation | TAP inhibitors, Proteasome inhibitors, Invariant chain siRNA | Antigen processing mechanism studies | Use controlled dosing with viability assays; include rescue experiments |

Frequently Asked Questions: Troubleshooting Guide

Q1: In our MLR experiments, we're consistently seeing high background proliferation in control wells containing only responder cells. What could be causing this and how can we reduce it?

A: High background proliferation often indicates suboptimal culture conditions or responder cell activation. Implement these troubleshooting steps:

- Verify that stimulator cell inactivation is complete by culturing stimulator cells alone and confirming no proliferation.

- Use fresh rather than frozen PBMCs if possible, as freeze-thaw cycles can increase background activation.

- Ensure FBS batch is thoroughly screened for low background stimulation; some serum lots contain bovine antigens that cross-react with human lymphocytes.

- Reduce culture time from 7 to 5 days to decrease background while maintaining alloresponse.

- Include additional washing steps after mitomycin C treatment to completely remove the chemical.

- Test different cell densities (0.5×10⁵ to 2×10⁵ cells/well) to find the optimal signal-to-noise ratio.

Q2: We're struggling to detect miHA-specific T-cell responses even when using donor-recipient pairs known to be mismatched for several minor antigens. What optimization strategies do you recommend?

A: Detecting miHA responses requires sensitive methods and careful optimization:

- Enhance T-cell priming by using mature dendritic cells as APCs rather than PBMCs.

- Add cytokine support (10-20 U/mL IL-2 and 5 ng/mL IL-7) after initial stimulation to promote T-cell expansion.

- Implement repeated stimulation cycles (weekly for 3-4 weeks) to expand rare miHA-specific T-cell clones.

- Use tetramer staining instead of functional assays if specific miHA epitopes are known.

- Consider the MHC restriction element - ensure your assay system includes the appropriate MHC molecule that presents the miHA.

- Try ELISpot assays which are typically more sensitive for detecting rare antigen-specific cells than proliferation or cytotoxicity assays.

Q3: Our flow cytometry analysis of HLA expression shows inconsistent results between experiments. What are the critical factors for reliable MHC quantification?

A: MHC expression measurement requires strict standardization:

- Implement calibration beads with known antibody binding capacity to standardize fluorescence quantification between experiments.

- Control for cytokine-mediated MHC modulation - ensure consistent culture conditions as IFN-γ can dramatically upregulate MHC expression.

- Use the same clone of MHC-specific antibody throughout your study as different clones recognize different epitopes with varying affinities.

- Include both positive and negative control cell lines with stable MHC expression in each experiment.

- Standardize fixation and permeabilization procedures if detecting intracellular MHC molecules.

- Ensure antibody titration for optimal signal-to-noise ratio in your specific experimental system.

Q4: We're investigating non-MHC barriers in transplantation and want to study the "missing self" hypothesis. What experimental model do you recommend?

A: Studying "missing self" recognition requires specific experimental designs:

- Implement an in vitro coculture system with purified human NK cells and allogeneic endothelial cells mismatched for MHC class I alleles [15].

- Use CRISPR/Cas9 to generate MHC class I knockout cell lines to create controlled "missing self" scenarios.

- Include KIR genotyping of NK cell donors and HLA typing of target cells to identify permissive and non-permissive interactions.

- Measure NK cell activation markers (CD107a, IFN-γ production) and target cell killing to quantify missing self responses.

- For in vivo modeling, consider F1 hybrid mouse models transplanted with parental strain grafts which naturally exhibit missing self recognition [15].

- Always include appropriate controls with MHC-matched combinations to distinguish missing self from other allorecognition pathways.

Emerging Concepts and Future Directions

Recent advances in transplantation immunology have revealed additional layers of complexity in histocompatibility. The discovery of innate allorecognition demonstrates that myeloid cells can directly recognize allogeneic non-self through mechanisms like the signal regulatory protein α-CD47 pathway [15]. This MHC-independent recognition challenges the traditional paradigm that alloimmunity is solely mediated by adaptive immunity.

Another significant development is the understanding that endogenous retrotransposable elements and antivimmune signatures can influence transplant outcomes. A 2025 study demonstrated that mouse melanoma cells capable of escaping allogeneic rejection upregulated retrotransposable elements, MHC class I, PD-L1, and Qa-1 non-classical MHC molecules [16]. Knockout of the RNA sensor RIG-I reduced expression of these immunosuppressive molecules, making tumors susceptible to rejection.

The field is also moving toward tolerance-inducing strategies rather than broad immunosuppression. Approaches including regulatory T-cell therapy, mixed chimerism induction, and thymic education are showing promise in clinical trials [17]. These strategies aim to reprogram the immune system to specifically accept donor antigens while maintaining overall immune competence, potentially eliminating the need for lifelong immunosuppression.

Core Concepts: The Basis of Humoral Rejection

What is the fundamental premise of the humoral theory of transplantation? The humoral theory of transplantation, pioneered by Professor Paul Terasaki, posits that antibodies are the primary mediators of allograft rejection. This theory challenges the historical focus on T-cells and emphasizes that antibodies can cause immediate and devastating graft destruction, from hyperacute rejection occurring within minutes to chronic rejection developing over years [18] [19].

What are the key antibodies and antigens involved in this process? The central actors are Donor-Specific Antibodies (DSA). These antibodies most commonly target donor Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) molecules, known in humans as Human Leukocyte Antigens (HLA)—specifically HLA class I (A, B, C) and class II (DR, DQ, DP) [18] [20]. Importantly, antibodies can also target non-HLA antigens on endothelial and epithelial cells, such as angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1R), endothelin-I type A receptor (ETAR), and vimentin [18].

How does antibody binding translate to physical damage in the graft? Antibody binding initiates a destructive cascade. DSA binding to donor endothelium triggers the classical complement pathway, leading to the formation of the Membrane Attack Complex (C5b-C9) that directly lyses endothelial cells [21] [22]. Complement split products (C3a, C5a) act as potent anaphylatoxins, recruiting inflammatory cells like neutrophils and monocytes. These cells, along with Natural Killer (NK) cells, further contribute to tissue damage through antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) and the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines [22]. The result is widespread endothelial injury, thrombosis, and ischemia, culminating in graft failure.

The diagram below illustrates this core mechanistic pathway of antibody-mediated graft injury.

Troubleshooting Guide: Experimental Challenges in AMR Research

Model Systems & Diagnosis

FAQ 1: How can I reliably detect and diagnose Antibody-Mediated Rejection in my experimental models? A multi-modal approach is critical for accurate AMR diagnosis. Relying on a single parameter often leads to false negatives or misinterpretation.

Table: Key Diagnostic Modalities for Experimental AMR

| Modality | Key Readouts | Experimental Significance | Common Pitfalls |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serology | Donor-Specific Antibody (DSA) detection via solid-phase assays (Luminex), C1q-binding assay to assess complement-fixing ability [18]. | Quantifies the humoral response. High Mean Fluorescence Intensity (MFI >1000) correlates with worse outcomes [18]. | DSA may be absorbed by the graft, leading to undetectable serum levels [19]. |

| Histopathology | Microvascular inflammation (glomerulitis, capillaritis), C4d deposition on peritubular capillaries (a footprint of complement activation) [21] [22]. | Provides direct evidence of tissue injury and complement activity. Considered a hallmark feature. | C4d staining can be negative in some AMR cases; injury can occur via complement-independent pathways [21]. |

| Graft Function | Serum creatinine (kidney), forced expiratory volume (lung), other organ-specific functional metrics [20] [23]. | Correlates immunological injury with clinical outcome. A persistent 20% drop in FEV1 indicates chronic lung rejection (BOS) [23]. | Functional changes are late markers; significant injury may occur before function declines. |

| Emerging Biomarkers | Donor-derived cell-free DNA (dd-cfDNA) for early graft injury [24]. | Highly sensitive for detecting early, subclinical graft injury, allowing for preemptive intervention. | Still being validated in various transplant settings; can be elevated in non-rejection injury (e.g., infection). |

FAQ 2: Our in vivo models are not consistently developing high-titer DSA. What could be limiting the humoral response? The robustness of a humoral response depends on effective T-B cell collaboration. Models using specific pathogen-free (SPF) rodents have a naïve immune system and may generate weaker responses compared to humans or "dirty" mice exposed to pathogens, which have a larger memory T-cell compartment [17]. Ensure your model has sufficient CD4+ T-cell help. The indirect pathway of allorecognition, where recipient T-cells recognize donor peptides presented by recipient Antigen-Presenting Cells (APCs), is critical for providing help to B-cells for antibody class switching and affinity maturation [20] [23]. Using donors with a greater degree of HLA/MHC mismatch can also potentiate a stronger DSA response.

Therapeutic Interventions

FAQ 3: We are testing a new B-cell targeting drug, but DSA levels are not decreasing. Why might this be? B-cell depletion strategies (e.g., anti-CD20 like Rituximab) effectively target precursor B-cells but have limited efficacy against antibody-secreting plasma cells, which are long-lived and do not express CD20 [21]. This is a common reason for therapeutic failure. To target plasma cells, you must employ proteasome inhibitors (e.g., Bortezomib), which induce endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis in these specialized, high-output cells [21] [22]. For a comprehensive effect, a combination therapy targeting both the B-cell lineage (anti-CD20) and plasma cells (proteasome inhibitor) is often necessary.

FAQ 4: Our complement inhibitor is effective in vitro, but failing in our in vivo model. What are potential mechanisms of resistance? Complement activation is a powerful effector mechanism, but it is not the only one. AMR can proceed via complement-independent pathways. In these cases, DSA binding alone can activate endothelial cells, leading to increased permeability and proliferation. Furthermore, DSA can recruit NK cells and monocytes via Fc gamma receptor (FcγR) engagement, triggering antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) and pro-inflammatory cytokine release, causing significant graft injury without complement [22]. Your therapeutic strategy should account for these alternative injury pathways.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Experimental Protocols

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Investigating Humoral Rejection

| Research Reagent / Tool | Primary Function in AMR Research |

|---|---|

| Anti-CD20 (e.g., Rituximab) | Depletes CD20+ B-cells, interrupting the precursor pool for plasma cells and memory B-cells [21] [22]. |

| Proteasome Inhibitor (e.g., Bortezomib) | Induces apoptosis in antibody-secreting plasma cells, directly reducing DSA production [21]. |

| C5 Inhibitor (e.g., Eculizumab) | Blocks the terminal complement cascade, preventing formation of the Membrane Attack Complex (MAC) [21]. |

| Intravenous Immunoglobulin (IVIG) | Modulates immune responses via multiple mechanisms, including neutralization of autoantibodies, Fc receptor blockade, and inhibition of complement activation [21]. |

| IL-6 Receptor Inhibitor (e.g., Tocilizumab) | Blocks IL-6 signaling, a key cytokine for B-cell differentiation into plasma cells and T-follicular helper (Tfh) cell function, disrupting germinal center responses [22]. |

| Anti-Thymocyte Globulin (ATG) | Polyclonal antibody preparation that depletes T-cells, thereby reducing T-cell help for B-cell activation and antibody production [21]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Assessing a Novel AMR Therapy

This protocol outlines a standard in vivo approach for evaluating the efficacy of a new therapeutic agent against established AMR.

Objective: To determine if Drug X ameliorates ongoing antibody-mediated damage and prolongs graft survival in a murine kidney transplant model.

Week 0-1: Model Establishment & Baseline Monitoring

- Induction: Perform allogeneic kidney transplantation on Day 0.

- Confirmation: On Day 7 post-transplant, collect serum and confirm DSA seropositivity via flow cytometric crossmatch or bead-based assay. Randomly enroll DSA+ animals into treatment or control groups.

Week 2: Therapeutic Intervention

- Dosing: Administer Drug X (treatment group) or Vehicle (control group) according to the planned regimen from Day 7 to Day 21.

- Monitoring: Weigh animals daily and monitor for signs of distress. Collect serial serum samples (e.g., Days 7, 14, 21) to track DSA levels and dd-cfDNA.

Week 3: Endpoint Analysis (Terminal Procedure)

- Functional Assessment: Measure serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) to assess graft function.

- Tissue Collection: Euthanize animals and harvest the graft.

- Perfuse one part of the graft with formalin for histology (H&E, C4d staining).

- Snap-freeze another part for RNA/protein extraction (e.g., for cytokine analysis).

- Process tissue for flow cytometry to quantify immune cell infiltration (CD45+, CD3+, CD20+, CD138+ cells).

- Histological Scoring: A pathologist blinded to the groups should score the tissue for features of AMR (e.g., Banff scores for glomerulitis (g), peritubular capillaritis (ptc), and C4d deposition).

The following workflow diagram summarizes this experimental design.

Advanced Research Frontiers

What are the emerging therapeutic targets beyond current standard-of-care? Research is moving beyond broad immunosuppression towards targeted disruption of the humoral immune response. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) is a pivotal cytokine in this context. It drives the differentiation of B-cells into plasma cells and supports the function of T-follicular helper (Tfh) cells within the germinal center, a critical site for high-affinity DSA generation [22]. Clinical trials are now investigating IL-6 receptor blockers (e.g., Tocilizumab) for treating chronic active AMR, showing promise in modulating this pathogenic axis.

Another frontier is the induction of transplant tolerance to eliminate the need for lifelong immunosuppression. Strategies include establishing donor hematopoietic chimerism, where donor stem cells engraft in the recipient, educating the immune system to accept the donor organ as "self" [17]. Alternatively, infusions of regulatory cell therapies (T-regs) are being explored to actively suppress the anti-donor immune response. While challenging, these approaches represent the ultimate goal in transplantation research [17].

Technical Support Center: FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the core molecular signature that defines the Immunologic Constant of Rejection (ICR)?

The Immunologic Constant of Rejection (ICR) describes a common, convergent effector pathway that is activated across various immune-mediated tissue destruction processes, including allograft rejection, autoimmunity, and responses to pathogens and cancer. Its core signature consists of the coordinate activation of two key element groups [25] [26]:

- Interferon-Stimulated Genes (ISGs): A consistent and prominent activation of genes regulated by interferon signaling.

- Immune Effector Functions (IEFs): The recruitment and activation of cytotoxic immune cells, leading to the expression of effector molecules like granzymes and perforin.

This pathway is often accompanied by the recruitment of immune cells via specific chemokine pathways, particularly those involving CXCR3 and CCR5 ligands [26].

FAQ 2: My gene expression data shows ISG activation in a transplant model. Does this automatically confirm the ICR and predict rejection?

Not necessarily. While the ICR hypothesis posits that ISG activation is a pillar of the rejection process, its presence must be interpreted in a broader context. You should investigate further by [26]:

- Checking for IEF Gene Co-expression: Confirm that the ISG signature is coupled with upregulated expression of immune effector function genes (e.g., granzymes A/B, perforin).

- Validating Cell Recruitment: Verify the upregulation of chemokines (e.g., CXCL9, CXCL10, CCL5) that recruit CXCR3/CCR5-expressing cytotoxic cells.

- Performing Pathway Analysis: Use tools to determine if the broader ICR network, not just isolated components, is significantly enriched.

The ICR represents a common final pathway, and its full signature provides a more reliable indicator of active rejection than any single component alone [25].

FAQ 3: What are the best practices for experimentally detecting alloreactive T cells in vivo?

Detecting rare, donor-reactive T cells is challenging. A recommended methodology is the Comprehensive Alloreactive T-cell Detection (cATD) Assay, which utilizes short-term mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR) and flow cytometry. Below is a detailed protocol adapted from recent research [27].

Experimental Protocol: cATD Assay for Alloreactive T-Cell Detection

| Step | Specification | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Stimulator Cell Prep | Isolate CD19+ B cells from donor spleen. Activate with CD40L (100 ng/mL) + IL-4 (10 ng/mL) for 24 hours. Irradiate (40 Gy) before co-culture. | Generates activated antigen-presenting cells from the donor to stimulate recipient T cells. |

| 2. Responder Cell Prep | Purify T cells from recipient splenocytes using negative selection. | Isbrates the recipient's T-cell population for the response assay. |

| 3. Co-culture & Staining | Co-culture stimulators and responders at a 1:1 ratio (10^6 cells each) for 18 hours. Include APC-conjugated anti-CD154 antibody in the culture medium. Add a protein transport inhibitor (e.g., monensin) for the last 4 hours. | Allows for direct antigen presentation and activation of alloreactive T cells. Anti-CD154 labels activated CD4+ T cells. |

| 4. Flow Cytometry | Stain cells for surface and intracellular markers. Identify alloreactive CD4+ T cells as CD3+CD4+CD154+. Identify alloreactive CD8+ T cells as CD3+CD8+CD137+. | Specifically labels and quantifies the activated, donor-reactive T-cell populations. |

This assay can detect alloreactive T cells as early as 7 days post-transplantation, even before visual graft rejection, and can help distinguish between rejection and tolerance models [27].

FAQ 4: How can I distinguish between acute and chronic rejection at the molecular level?

Acute and chronic rejection are driven by distinct yet sometimes overlapping immune mechanisms. The following table summarizes key differences based on clinical and experimental observations [28] [29].

Table 1: Differentiating Acute and Chronic Rejection

| Feature | Acute Rejection | Chronic Rejection |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Onset | First few months to a year post-transplant [29]. | Develops after a year or more, often a long-term problem [29]. |

| Primary Mediators | Direct T-cell allorecognition; prominent cytotoxic T-cell and innate immune activation [30]. | Involves indirect allorecognition; associated with alloantibodies and macrophage-mediated tissue fibrosis [30]. |

| ICR Signature | Often presents a strong, canonical ICR signature with clear ISG and IEF activation [26]. | The ICR signature may be less prominent or accompanied by a stronger fibrotic and antibody-mediated gene expression profile. |

| Histology | Cell-mediated attack on graft parenchyma. | Tissue remodeling, fibrosis, and vascular occlusion. |

FAQ 5: What are the major challenges in applying the ICR hypothesis to allogeneic cell therapies?

The primary challenge is immune rejection of the allogeneic cell product, which rapidly eliminates the therapy. Overcoming this requires strategies to evade the host immune system, a concept often termed "alloevasion" [31]. Key hurdles include:

- T-cell Recognition: Host CD8+ and CD4+ T cells recognize foreign HLA Class I and II molecules on the donor cells [31].

- Antibody-Mediated Rejection: Host B cells can produce alloantibodies that trigger complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) [31].

- NK Cell Activation: Host NK cells attack donor cells that lack "self" HLA molecules [31].

- Immune Memory: A second dose of the therapy is often cleared more rapidly due to primed memory T and B cells [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for ICR & Rejection Studies

| Reagent / Assay | Primary Function | Application in Rejection Research |

|---|---|---|

| cATD Assay [27] | Detects activated alloreactive T cells via CD154 (CD4+) and CD137 (CD8+) expression. | Monitoring pre- and post-transplant anti-donor T-cell responses; evaluating tolerance. |

| CXCR3/CCR5 Ligands (e.g., CXCL9, CXCL10, CCL5) [26] | Chemoattractants for T cells and NK cells. | Biomarkers for the recruitment of cytotoxic effector cells to the graft; part of the ICR signature. |

| IEF Gene Panel (Granzymes A/B, Perforin) [26] | Mediates target cell apoptosis and cytolysis. | Quantifying the effector phase of rejection; a core component of the ICR. |

| Anti-HLA Antibody Detection Assays | Measures allospecific antibody titers in serum. | Assessing humoral sensitization and risk of antibody-mediated rejection. |

| Lymphodepleting Agents (e.g., Cyclophosphamide, Fludarabine) [31] | Depletes host lymphocytes transiently. | A preconditioning regimen to reduce host-versus-graft reactivity and enhance engraftment of allogeneic therapies. |

Experimental Workflow & Pathway Visualization

The diagram below illustrates the core experimental workflow for profiling the ICR signature and the key molecular pathways involved.

The tables below consolidate key quantitative findings from recent studies to aid in experimental design and data benchmarking.

Table 3: Microbiota Diversity & Transplant Outcomes in Pediatric Allo-HSCT (n=90) [32]

| Patient Group | Overall Survival (OS) | Incidence of Grade 2-4 aGVHD | Key Microbial Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Higher Pre-Tx Diversity | 88.9% ± 5.7% SE | Lower | Higher abundance of SCFA-producing taxa (e.g., Ruminococcaceae). |

| Lower Pre-Tx Diversity | 62.7% ± 8.2% SE | Higher | Overabundance of potential pathogens (e.g., Enterococcaceae). |

Table 4: Immune Cell Dynamics in Mouse Skin Transplant Rejection Models [27]

| Transplant Model | Immune Status | Donor-Reactive CD8+ T Cells (Day 7) | Graft Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| BALB/c → C57BL/6 | Rejection | Increased Proportion | Rejection |

| BALB/c → C3H/HeJ | Tolerance (with immunosuppression) | Lower Proportion | Acceptance |

FAQs: Understanding the Fundamentals of Transplant Rejection

Q1: What are the primary immunological drivers of hyperacute, acute, and chronic rejection?

The immune mechanisms differ significantly across rejection types. Hyperacute rejection is driven by pre-existing antibodies in the recipient against donor antigens (e.g., ABO blood group or HLA antigens) [33] [34]. These antibodies activate the complement cascade immediately upon revascularization, leading to widespread thrombosis and graft necrosis [35] [24].

Acute rejection primarily involves adaptive immunity. Acute T-cell-mediated rejection (TCMR) is characterized by T lymphocytes infiltrating the graft and causing damage upon recognizing foreign donor antigens [35] [33]. Acute antibody-mediated rejection (ABMR) is caused by donor-specific antibodies (DSA), often developed de novo post-transplant, which attack the vascular endothelium, triggering microvascular inflammation [35] [24].

Chronic rejection is a slow, progressive process often involving both immune and non-immune factors. Chronic active ABMR is a major cause of long-term graft loss, driven by persistent DSA leading to microvascular injury, fibrosis, and arterial intimal thickening [35] [33].

Q2: How is a definitive diagnosis of rejection established and classified?

The gold standard for diagnosis is histopathological examination of a graft biopsy, interpreted according to the international Banff Classification System [35] [33]. This system provides standardized criteria for diagnosing and grading rejection, categorizing findings based on the type and severity of tissue injury [35].

table: Banff Classification Categories for Renal Allograft Biopsy

| Category | Diagnosis | Key Pathological Features |

|---|---|---|

| Category 1 | Normal | Normal tissue or nonspecific changes [33] |

| Category 2 | Antibody-Mediated Rejection (ABMR) | Microvascular inflammation (glomerulitis, peritubular capillaritis), C4d deposition, or chronic changes like transplant glomerulopathy [35] [33] |

| Category 3 | Borderline/Suspicious for TCMR | Focal tubulitis and mild interstitial inflammation [33] |

| Category 4 | T-Cell-Mediated Rejection (TCMR) | Significant lymphocytic infiltration in tubules (tubulitis), interstitium, and/or arteries [35] [33] |

| Category 5 | Interstitial Fibrosis and Tubular Atrophy (IFTA) | Scarring indicative of chronic injury [33] |

| Category 6 | Other Changes | Lesions not considered rejection (e.g., viral infection) [33] |

Q3: What are the key risk factors for transplant rejection?

Multiple factors correlate with an increased risk of rejection [33]:

- Immunological Factors: Prior sensitization (high panel reactive antibodies), HLA mismatch, positive B-cell crossmatch, and ABO incompatibility.

- Donor/Transplant Factors: Deceased donor (vs. living donor), advanced donor age, prolonged cold or warm ischemia time.

- Recipient Factors: Younger age, Black race, non-compliance with immunosuppressive therapy, and previous rejection episodes.

Troubleshooting Guides: From Diagnostic Challenges to Research Models

Guide 1: Investigating Subclinical Rejection and Early Graft Injury

Challenge: A rise in serum creatinine is a late indicator of graft injury. Detecting rejection at an early, potentially reversible stage is critical for intervention [24].

Solution: Implement non-invasive biomarker monitoring alongside protocol biopsies.

table: Emerging Non-Invasive Biomarkers for Rejection Monitoring

| Biomarker | Substrate | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA (dd-cfDNA) | Blood | Highly sensitive marker for early graft injury; elevated levels indicate active cell death from rejection [24]. |

| Gene Expression Profiling (GEP) | Blood | Can exclude moderate-to-severe acute rejection; analyzes patterns of immune cell activation [24]. |

| MicroRNA (miRNA) Profiling | Blood/Urine | Enhances diagnostic specificity for precise detection of acute rejection [24]. |

| Donor-Specific Antibodies (DSA) | Blood | Diagnostic biomarker for Antibody-Mediated Rejection (ABMR); detection is a key criterion for diagnosis [35] [33]. |

Experimental Protocol: Monitoring dd-cfDNA in a Rodent Transplant Model

- Model Establishment: Induce end-stage renal disease in a recipient rodent and perform an allogeneic kidney transplant.

- Sample Collection: Collect peripheral blood (e.g., 200µL) weekly from recipient animals into EDTA tubes. Centrifuge at 1,600 x g for 10 min to separate plasma.

- cfDNA Extraction: Use a commercial cfDNA extraction kit to isolate total cfDNA from 1-4 mL of plasma.

- dd-cfDNA Quantification:

- Method A (qPCR-based): Design primers and probes for Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) that differ between donor and recipient. Use droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) for absolute quantification. Calculate the fraction of dd-cfDNA as (donor allele copies / total allele copies) x 100% [24].

- Method B (NGS-based): Perform shallow whole-genome sequencing of the cfDNA. Use bioinformatic algorithms to detect donor- and recipient-specific SNPs and calculate the dd-cfDNA fraction.

- Correlation: Correlate dd-cfDNA levels with simultaneous graft function tests and histology from terminal biopsies to validate its predictive value.

Guide 2: Differentiating T-Cell-Mediated vs. Antibody-Mediated Rejection in Research

Challenge: Accurately distinguishing between TCMR and ABMR in an experimental setting, as their treatments differ significantly.

Solution: A multi-modal approach combining histology, immunostaining, and serology.

Experimental Protocol: Differentiating Rejection Types in a Murine Model

- Graft Biopsy & Histology:

- Immunofluorescence/Immunohistochemistry:

- For ABMR: Stain for C4d on frozen or paraffin-embedded tissue. Linear staining in peritubular capillaries is a hallmark of classical complement activation [33].

- For Immune Cell Infiltration: Use antibodies against CD3 (T cells), CD20 (B cells), and CD68 (macrophages) to characterize the inflammatory infiltrate.

- Serological Analysis:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Models

table: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Transplant Rejection

| Reagent / Material | Function & Application in Rejection Research |

|---|---|

| Anti-T cell Depleting Antibodies (e.g., Anti-CD3) | Used in vivo to deplete T lymphocytes and study their critical role in acute T-cell-mediated rejection [17]. |

| Complement Inhibitors (e.g., Anti-C5) | Used to block the complement cascade, investigating its role in hyperacute and antibody-mediated rejection [35]. |

| Recombinant Cytokines & Neutralizing Antibodies | To manipulate specific immune pathways (e.g., IL-2, IFN-γ) and assess their impact on rejection or tolerance [17]. |

| MHC-Tetramers | For tracking and characterizing donor-reactive T cells in the recipient's immune system using flow cytometry. |

| Luminex Bead Arrays | High-sensitivity multiplex assay for detecting and quantifying donor-specific antibodies (DSA) in recipient serum [24]. |

| C4d Antibody | Critical immunohistochemistry reagent for diagnosing antibody-mediated rejection by detecting complement split product deposition [33]. |

| Allogeneic Mouse Strains | Research models with defined MHC mismatches (e.g., C57BL/6 to BALB/c) to study immune responses in a controlled setting. |

| CRISPR-Cas Gene Editing Tools | For generating genetically modified donor cells or organs (e.g., knocking out MHC molecules) to evade immune recognition [36] [37]. |

From Bench to Bedside: Current and Novel Intervention Strategies

Troubleshooting Guides for Common Experimental Challenges

Problem 1: Unexpectedly High Rates of Graft Rejection in Preclinical Models

Potential Cause: Inadequate therapeutic drug monitoring leading to subtherapeutic immunosuppressant levels.

- Solution: Implement rigorous therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM). For calcineurin inhibitors like tacrolimus, target trough levels of 5-15 ng/mL in the first month post-transplant, adjusting based on rejection risk [38]. For cyclosporine, monitor levels 2 hours post-dose (C2 monitoring) with targets of 1.2-1.7 μg/mL [38].

- Experimental Protocol: Collect blood samples at consistent times relative to dosing. Use validated immunoassays (ELISA) or liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) for precise quantification. Include dose-response curves with known standards to ensure assay accuracy.

Potential Cause: Inappropriate drug formulation or administration route affecting bioavailability.

- Solution: For oral administration in rodent models, ensure proper formulation. Tacrolimus can be suspended in 0.5% methylcellulose, while cyclosporine requires olive oil or cremophor-based vehicles due to poor aqueous solubility [38]. Confirm homogeneous suspension through visual inspection and vortexing immediately before administration.

- Experimental Protocol: Compare bioavailability between administration routes. For IV delivery in mice, dissolve tacrolimus in normal saline with 10% ethanol at 0.1 mg/mL, administering 0.1-0.3 mg/kg. For oral dosing, use 1-5 mg/kg via oral gavage after 4-hour fasting to reduce food effects.

Problem 2: Excessive Immunosuppression Leading to Infection in Experimental Models

Potential Cause: Narrow therapeutic window of conventional immunosuppressants.

- Solution: Implement combination therapy at reduced doses. The "Belatacept-Mycophenolate-Low Dose Tacrolimus" regimen allows calcineurin inhibitor minimization while maintaining efficacy [38]. In murine models, combine mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) at 30 mg/kg/day with sirolimus at 0.5 mg/kg/day rather than high-dose monotherapy.

- Experimental Protocol: Establish dose-escalation studies for combination therapies. Begin with 50% of typical monotherapy doses and titrate based on weekly flow cytometry analysis of T-cell counts (aim for CD3+ count >200 cells/μL) and monthly pathogen screening.

Potential Cause: Drug accumulation due to impaired metabolism.

- Solution: Monitor for drug-drug interactions and hepatic function. Cyclosporine and tacrolimus are metabolized by cytochrome P450 3A4; avoid co-administration with strong CYP3A4 inhibitors (e.g., ketoconazole) or inducers (e.g., rifampin) in experimental models [38].

- Experimental Protocol: Include control groups receiving CYP3A4 modulators when testing new drug combinations. Measure serum transaminases (ALT, AST) weekly and adjust dosing if levels exceed 3× upper limit of normal.

Problem 3: Drug-Related Toxicity in Primary Cell Cultures

Potential Cause: Direct cytotoxic effects at standard concentrations.

- Solution: Optimize in vitro dosing using viability assays. For calcineurin inhibitors, start with 5-10 ng/mL for tacrolimus or 50-100 ng/mL for cyclosporine in human T-cell cultures, rather than typical therapeutic ranges of 10-20 ng/mL and 100-300 ng/mL respectively [38].

- Experimental Protocol: Perform MTT or Annexin V/PI staining assays after 72-hour exposure. Calculate IC50 values for both immunosuppression (IL-2 inhibition) and cytotoxicity (viability reduction). Select concentrations where efficacy/toxicity ratio is maximized.

Potential Cause: Solvent toxicity from drug vehicles.

- Solution: Use alternative solubilization methods. Replace DMSO with cyclodextrin complexes for sirolimus (maximum 0.1% final concentration), or use ethanol-based vehicles for calcineurin inhibitors with final ethanol concentration <0.5% [38].

- Experimental Protocol: Include vehicle-only controls in all experiments. Assess cell viability and function after 24, 48, and 72 hours of exposure. Pre-test all vehicle solutions on relevant cell lines before primary cell experiments.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key mechanistic differences between calcineurin inhibitors and mTOR inhibitors?

Calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus, cyclosporine) and mTOR inhibitors (sirolimus, everolimus) target distinct signaling pathways in T-cell activation, as illustrated below:

Calcineurin inhibitors block the phosphatase activity of calcineurin, preventing nuclear translocation of NFAT (Nuclear Factor of Activated T-cells) and subsequent IL-2 transcription [38]. mTOR inhibitors bind to FKBP-12 and block the mammalian Target of Rapamycin (mTOR), arresting cell cycle progression at the G1-S phase by inhibiting ribosomal protein synthesis and preventing IL-2-driven T-cell proliferation [38].

Q2: How do I select the appropriate primary endpoint for evaluating novel immunosuppressant efficacy in preclinical transplantation models?

The optimal endpoints depend on your experimental timeline and research question:

- Short-term (7-14 days): Flow cytometric analysis of T-cell activation markers (CD25, CD69, HLA-DR) and mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR) assays.

- Medium-term (2-4 weeks): Histopathological grading of allograft rejection using Banff classification for organ-specific features [39].

- Long-term (4-12 weeks): Graft survival analysis with serial monitoring of organ function (e.g., serum creatinine for kidney, bilirubin for liver) and donor-specific antibody (DSA) production.

Q3: What strategies can overcome calcineurin inhibitor nephrotoxicity in experimental models?

Three primary approaches have demonstrated efficacy:

- CNI Minimization: Combine low-dose tacrolimus (trough 3-5 ng/mL) with adjunctive agents like MMF (1-1.5 g/day equivalent) or sirolimus (trough 4-8 ng/mL) [38].

- CNI Conversion: Switch from CNI to mTOR inhibitors after 3-6 months, particularly in models with established renal dysfunction.

- Novel Formulations: Use extended-release tacrolimus formulations that produce more stable blood levels and reduce nephrotoxic peaks.

Q4: How can I distinguish between drug-induced nephrotoxicity and rejection in animal models?

Key differentiating features include:

- Timing: CNI nephrotoxicity typically develops gradually over weeks, while rejection often occurs abruptly.

- Histopathology: CNI toxicity shows arteriolar hyalinosis, striped interstitial fibrosis, and tubular atrophy; rejection demonstrates tubulitis, intimal arteritis, and inflammatory infiltrates [38].

- Biomarkers: Urinary NGAL and serum Cystatin C rise earlier in rejection than serum creatinine.

- Therapeutic Response:

- Drug Toxicity: Improves with dose reduction (improvement within 5-7 days)

- Rejection: Requires intensified immunosuppression (improvement within 2-3 days)

Q5: What are the critical in vitro assays for screening novel immunosuppressants?

Establish a tiered testing approach:

- Primary Screening: T-cell proliferation assays using CFSE dilution or 3H-thymidine incorporation with anti-CD3/CD28 stimulation.

- Mechanistic Studies: Calcium flux assays for calcineurin inhibitors; phospho-protein flow cytometry for mTOR inhibitors (pS6, p4E-BP1).

- Functional Assays: Cytokine multiplex analysis (IL-2, IFN-γ, IL-6, TNF-α) and regulatory T-cell induction assays.

- Specificity Testing: Toxicity panels on non-immune cells (hepatocytes, renal tubular cells) and antibacterial T-cell assays.

Quantitative Data Analysis

Table 1: Efficacy of Common Immunosuppressants in Preventing Acute Rejection

| Drug/Regimen | Mechanism of Action | Rejection Rate (%) | Key Toxicities | Therapeutic Monitoring Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tacrolimus | Calcineurin inhibitor | 10-20 [38] | Nephrotoxicity, neurotoxicity, NODAT | Trough: 5-15 ng/mL [38] |

| Cyclosporine | Calcineurin inhibitor | 15-25 [38] | Nephrotoxicity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia | C2: 1.2-1.7 μg/mL [38] |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | IMPDH inhibitor | 15-20 (monotherapy) [40] | Gastrointestinal, hematological | AUC: 30-60 mg·h/L [38] |

| Sirolimus | mTOR inhibitor | 20-30 (monotherapy) [38] | Hyperlipidemia, impaired wound healing, pneumonitis | Trough: 4-12 ng/mL [38] |

| Tacrolimus + MMF | Combination therapy | 5-12 [38] | Combined toxicities, increased infection risk | Tacrolimus: 5-10 ng/mL; MMF: AUC 30-60 mg·h/L |

Table 2: Experimental Dosing Conversion Between Species

| Drug | Human Dose | Mouse Equivalent | Rat Equivalent | Critical Administration Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tacrolimus | 0.1-0.15 mg/kg/day [38] | 1-5 mg/kg/day oral [38] | 0.5-3 mg/kg/day oral | Administer via oral gavage; monitor weight loss >15% |

| Cyclosporine | 10-15 mg/kg/day [38] | 10-25 mg/kg/day oral [38] | 5-15 mg/kg/day oral | Formulate in olive oil; highly variable bioavailability |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 1-1.5 g twice daily [40] | 30-60 mg/kg/day oral [40] | 20-40 mg/kg/day oral | Split dose BID; GI toxicity common at higher doses |

| Sirolimus | 2-6 mg/day loading, then 2 mg/day [38] | 0.5-1.5 mg/kg/day oral [38] | 0.3-1 mg/kg/day oral | Use fresh preparation; unstable in solution |

Signaling Pathway Visualization

T-cell Activation and Immunosuppressant Targets

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Immunosuppressant Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Products | Research Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calcineurin Inhibitors | Tacrolimus (FK506), Cyclosporine A | T-cell activation studies, graft rejection models | Light-sensitive; requires ethanol or DMSO solubilization; monitor stability in culture media |

| mTOR Inhibitors | Sirolimus (Rapamycin), Everolimus | Cell cycle studies, cancer immunotherapy combinations | Poor aqueous solubility; use cyclodextrin complexes; short half-life in culture |

| Antimetabolites | Mycophenolate mofetil, Azathioprine | Lymphocyte proliferation assays, combination therapy studies | MMF requires conversion to active MPA form; cell-type specific sensitivity |

| Detection Assays | LC-MS/MS kits, ELISA kits (Prometheus, ThermoFisher) | Therapeutic drug monitoring, pharmacokinetic studies | LC-MS/MS gold standard for CNIs; cross-reactivity issues with some ELISAs |

| Functional Assays CFSE Cell Division, IL-2 ELISpot, Phospho-flow cytometry | Mechanism of action studies, biomarker development | Optimize stimulation conditions (anti-CD3/CD28 concentration); include activation controls | |

| Animal Models | MHC-mismatched cardiac/kidney allograft models, Humanized mice | In vivo efficacy testing, translational studies | Strain-specific responses; monitor for species-specific metabolism differences |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Common Experimental Challenges and Solutions

FAQ: Why is our tolerogenic protocol, successful in mice, failing when translated to non-human primates or human cellular models?

- Answer: A primary cause is the difference in immune system history between specific pathogen-free (SPF) laboratory mice and humans. Humans possess a substantial compartment of memory T cells generated from lifelong pathogen exposure. These memory T cells, including those generated via heterologous immunity, are highly resistant to tolerance induction protocols that are effective in naive murine immune systems. Infection of a laboratory mouse with a single pathogenic virus can render it refractory to tolerance induction [41].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Validate Your Model: Consider using non-SPF animal models (e.g., "dirty mice" or pet store-derived mice) whose T cell memory profile more closely resembles that of adult humans [41].

- Pre-screen for Reactivity: Implement assays to detect pre-existing donor-reactive memory T cells in your recipient subjects before protocol initiation.

- Protocol Augmentation: Enhance your conditioning regimen to more effectively target and deplete memory T cell populations.